Magazzino Italian Art, Cold Spring, New York

2 October 2020 – 11 January 2021

by LILLY WEI

Bochner Boetti Fontana, the elegant exhibition on view until 11 January 2021, is installed in one of Magazzino Italian Art’s equally elegant galleries, recently reopened. Located in Cold Spring in the Hudson River valley, now ablaze with autumnal colour, it is well worth the 90-minute drive from New York City, offering a serene time-out zone during the ongoing pandemic. If you are concerned about safety, so is the museum, which adheres stringently to coronavirus guidelines, including advance appointments, very few visitors at a time, temperature checks and a gizmo to be worn that flashes red when the social distance rule is breached.

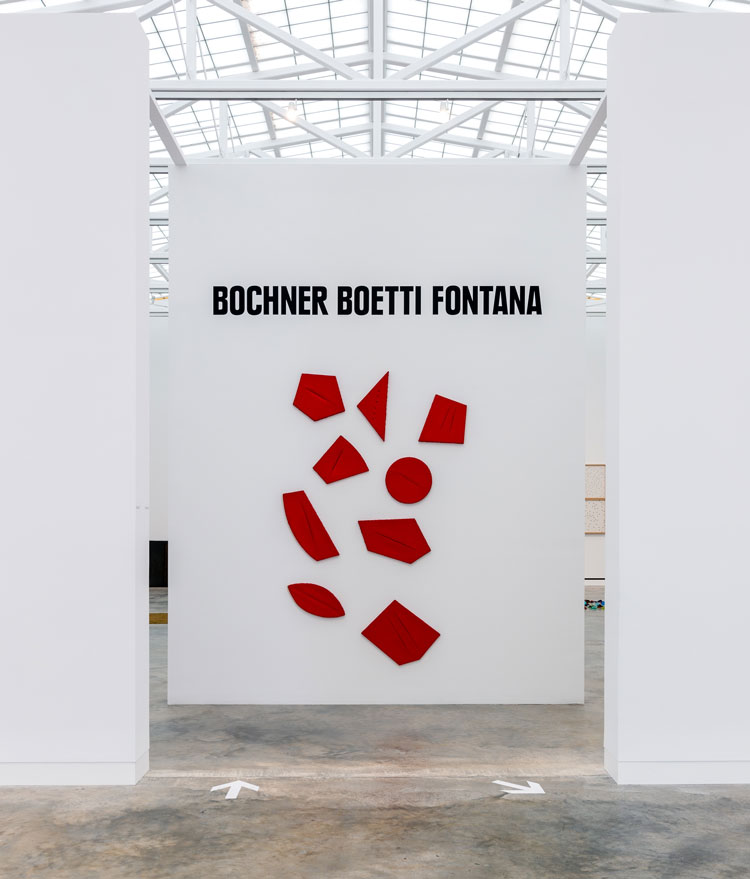

Bochner Boetti Fontana, installation view, Magazzino Italian Art 2 October – 11 January 2020. Photo: Alexa Hoyer. Courtesy of Magazzino Italian Art.

Founded in 2017 by collectors Nancy Olnick and Giorgio Spanu, it is dedicated to Italian postwar and contemporary art and, as another incentive to visit, there is an excellent, ongoing exhibition of the big guns of arte povera (Alighiero Boetti, Jannis Kounellis, Mario Merz, Marisa Merz, Giuseppe Penone, Michelangelo Pistoletto, and more from the collection), occupying the several other generously scaled, skylighted rooms of the spare, high-ceilinged 20,000 square foot centre designed by the architect Miguel Quismondo.

Magazzino Italian Art, Cold Spring, New York, exterior view. Photo: Marco Anelli.

The pioneering American conceptualist Mel Bochner, the curator of the show, noted that the history of his engagement with Italian art began nearly a decade before he went to Italy. He amusingly recounted his introduction as a student to Lucio Fontana’s work at the Carnegie International Exhibition of 1961. Seeing the slash in the canvas, horrified that someone had vandalised the painting, he immediately alerted the security guard. A few years later, after seeing Italian fresco paintings at a blockbuster exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, he became enamoured of trecento and quattrocento painters and was inspired by them to work directly on to the wall.

Bochner Boetti Fontana, installation view, Magazzino Italian Art 2 October – 11 January 2020. Photo: Alexa Hoyer. Courtesy of Magazzino Italian Art.

But it was not until 1969, when he was included in the landmark post-minimalist exhibition When Attitude Becomes Form, in Berne, curated by Harald Szeemann, that he saw in greater depth what contemporary European artists, among them Boetti, were making. Their thinking mirrored his own, the emphasis on process, seriality, the use of commonplace, ephemeral materials, text, mathematics, photographic documentation and, often and perhaps most divergent from American minimalism and conceptualism, a sense of play that sparred with the serious. The following year, Bochner was given a solo show at the Galleria Sperone in Turin, the first of many in Italy in what would become a mutual admiration society. There, he met Boetti for the first time.

Bochner Boetti Fontana, installation view, Magazzino Italian Art 2 October – 11 January 2020. Photo: Alexa Hoyer. Courtesy of Magazzino Italian Art.

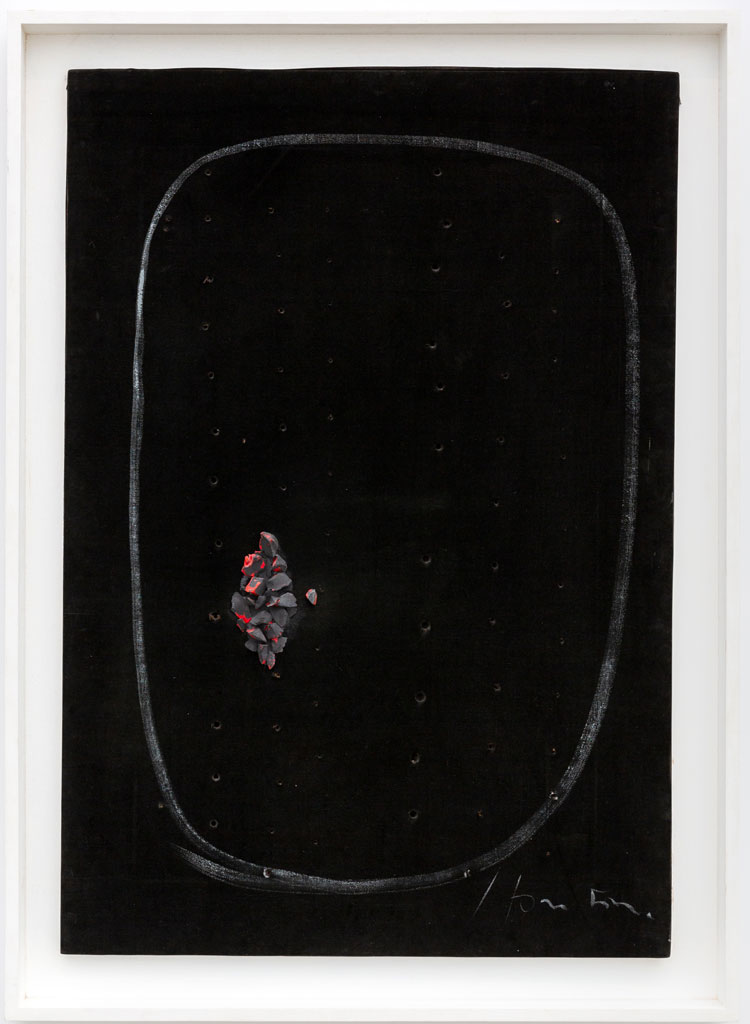

Of the 18 works in the show, the earliest is a Concetto Spaziale on black velvet by Fontana from 1956, the year of his first buchi (holes) paintings, constellated with tiny punctures and a cluster of coloured glass shards, launching his lifelong investigations into space, colour, sound and movement as a function of time.

Bochner Boetti Fontana, installation view, Magazzino Italian Art 2 October – 11 January 2020. Photo: Alexa Hoyer. Courtesy of Magazzino Italian Art.

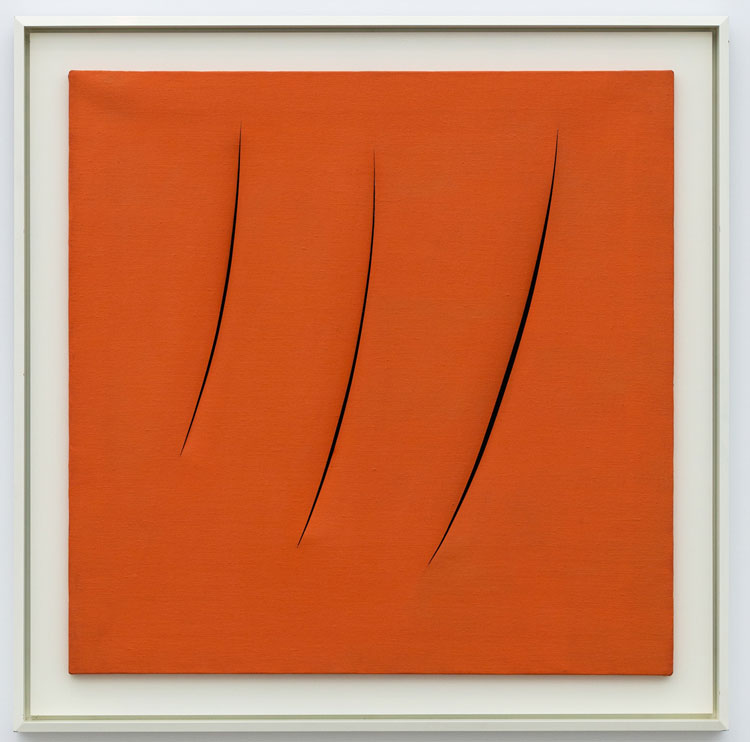

A more iconic Fontana is the Concetto Spaziale, Attese (1959), a stunning burnt orange square with three curved slashes. And his nine-part Concetto Spaziale, Quanta (1960) is given marquee status on the freestanding wall at the entrance to the gallery.

Lucio Fontana, Concetto Spaziale, Quanta, 1960. Bochner Boetti Fontana, installation view, Magazzino Italian Art 2 October – 11 January 2020. Photo: Alexa Hoyer. Courtesy of Magazzino Italian Art.

That honour is qualified by what seems a curious lapse of scrupulousness in an otherwise scrupulous installation: the placement of the title of the show just above it. Nonetheless, Quanta, painted a vivid red, holds its own, the small, mostly irregular, slashed and holed geometric shapes are juxtaposed into a kind of force field that might not be state-of-the-art technology, but nonetheless emit their own potent phenomenological charge.

Boetti was considered an exemplary arte povera artist, but then veered off towards more unorthodox enterprises based on presciently idiosyncratic collaborations (notably, even with himself for a time as Alighiero e Boetti), as well as delving into questions about artistic identity, authorship and doubling. His obsessive interest in systems and patterns, wordplay, alphabet and number games, and in mathematical calculations, shared by Bochner, is concisely presented in six works. Among them is Da mille a mille (1975), consisting of 11 sheets of graph paper, each with 1,000 squares – the number 1 and 0 of metaphoric and mathematic significance, done in black ballpoint pen, a medium he used handily in his Biro drawings.

Alighiero Boëtti, Teresa Giancarlo Carlotta Beatrice, 1977. Bochner Boetti Fontana, installation view, Magazzino Italian Art 2 October – 11 January 2020. Photo: Alexa Hoyer. Courtesy of Magazzino Italian Art.

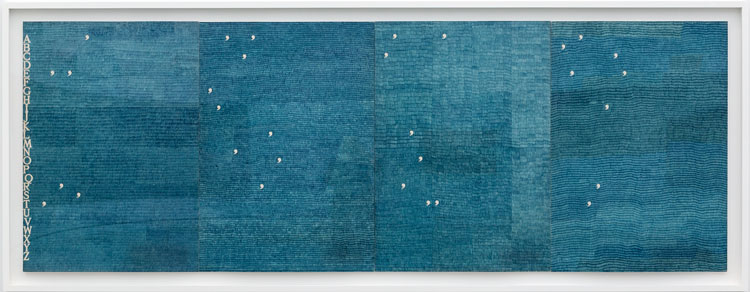

Another ambitious example here is Teresa Giancarlo Carlotta Beatrice (1977) in blue ballpoint ink, measuring nearly 10 feet across. As in other works of his, he invented the game and the rules, but allowed his collaborators the freedom to make their own choices within the given parameters. He was also fascinated by the accidental and the greater world, travelling to Afghanistan and Pakistan, among several lesser-visited countries before globetrotting artists became the norm, and incorporating other cultures into his work. Among his favoured places was Kabul where he worked with local craftswomen, commissioning them to embroider his sumptuous Arrazzi (tapetries) series. Alternandosi e dividendosi (1989), in full colour, made in collaboration with a Sufi master from Peshawar and the Afghan weavers, combines Italian and Farsi, the title referring to order and disorder, another instance of mixing letters, words and numbers in ways that initially seem rational, but collapse into a wilful subjectivity.

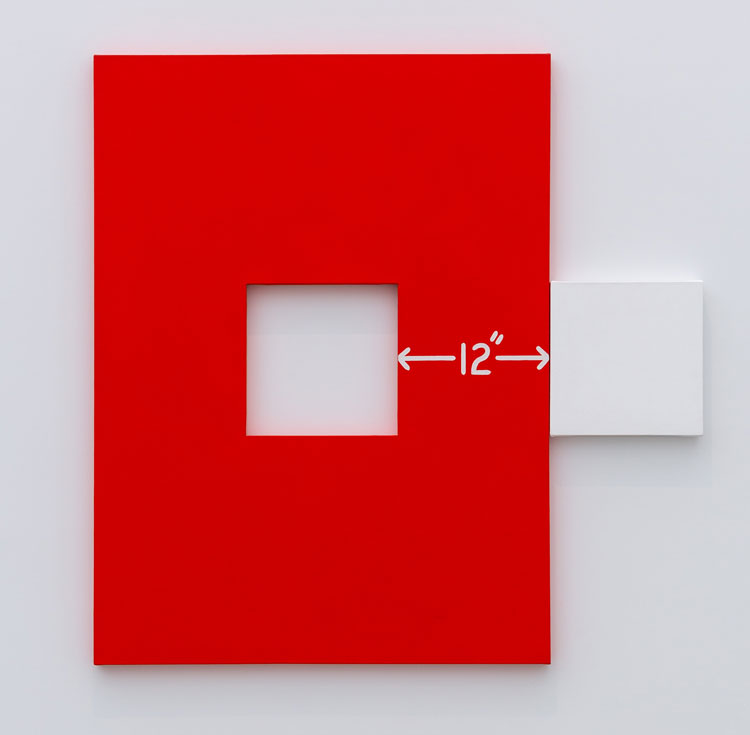

Mel Bochner, Measurement: 12 inches Between, 1999. Bochner Boetti Fontana, installation view, Magazzino Italian Art 2 October – 11 January 2020. Photo: Alexa Hoyer. Courtesy of Magazzino Italian Art.

Bochner is represented by eight works, among them the striking Measurement: 12 inches Between (1999) from his well-known Measurement series. Counting also figures prominently in his repertoire, represented here by Counting: 24 Trajectories (1997) and other recognisable works anchored in mathematical calculations and systems, in direct dialogue with Boetti, and in a more subtle exchange with Fontana.

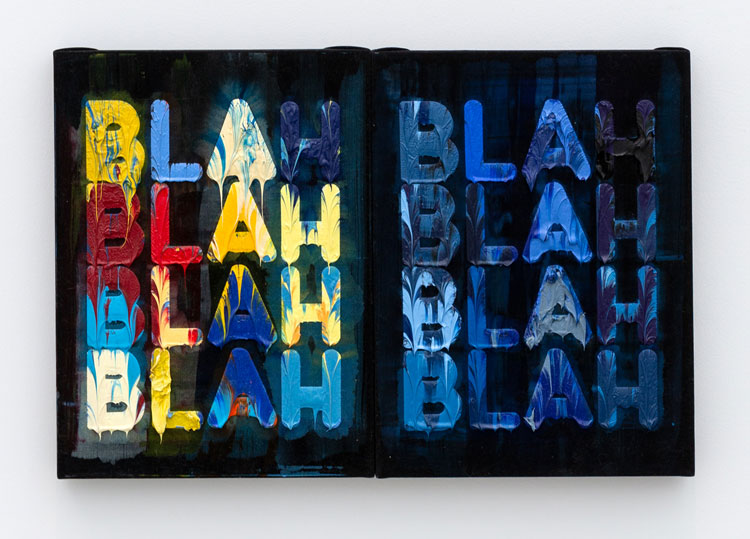

Mel Bochner, Blah Blah Blah, 2009. Bochner Boetti Fontana, installation view, Magazzino Italian Art 2 October – 11 January 2020. Photo: Alexa Hoyer. Courtesy of Magazzino Italian Art.

Bochner’s word paintings on velvet, the mocking, Blah Blah Blah (2009) and Complain (2007), from his Thesaurus series, the title a verb to parallel the pictorial activism of the text, and the wall painting, Language Is Not Transparent (1970/2019) remain bracing, arcing between sensuous painterly image, the lexical and their subversion and siphoning.

Bochner Boetti Fontana, installation view, Magazzino Italian Art 2 October – 11 January 2020. Photo: Alexa Hoyer. Courtesy of Magazzino Italian Art.

But it is the sotto voce connective threads that are the most appealing – and for a conceptual show, it is remarkably lush, even glamorous. For instance, Bochner’s floor installation Meditation on the Theorem of Pythagoras (1972/1993) has never looked better, the sparkling nuggets of jewel-like Murano glass arranged in a diagram of the foundational mathematical equation (a2 + b2 = c2) would not be out of place in a Bulgari window display. And the link is the source of the glass, from Fontana’s studio. In turn, the glass chunks are connected to those in Fontana’s Concetto Spaziale, its plush black velvet ground making us re-evaluate velvet and the velvet support of Bochner’s word paintings. In turn, we are reminded of Boetti’s embroidered Tavola Pitagorica (1990), the title evoking the Greek philosopher yet again. And once there, we see that Blah Blah Blah, with all its ambiguities, is strategically placed beneath it. And don’t forget to look for Fontana’s text piece scrawled on paper, a quintessential arte povera tease, or a harbinger of today’s constant spin.

Mel Bochner, Yiskor (For the Jews of Rome), 1993. Bochner Boetti Fontana, installation view, Magazzino Italian Art 2 October – 11 January 2020. Photo: Alexa Hoyer. Courtesy of Magazzino Italian Art.

Then there is Bochner’s other floor piece, the poignant Yiskor (For the Jews of Rome) (1993), consisting of burnt matchsticks arranged in the shape of a Jewish star on a US army blanket to signify the liberation of Rome in 1944 by the Allies. The word yizkor means to remember, as well as signifying a memorial service in Yiddish, a language that appears time and again in his work, sounding an autobiographical note that is coincident with today’s more personalised culture.

Mel Bochner, Yiskor (For the Jews of Rome), 1993 (detail). Bochner Boetti Fontana, installation view, Magazzino Italian Art 2 October – 11 January 2020. Photo: Alexa Hoyer. Courtesy of Magazzino Italian Art.

Bringing together artists from the 19th century to the present, this engaging exhibition kicks off t...

Taking its title from an Oscar Wilde short story, this group show whose setting echoes the salons an...

Something Else Entirely: The Illustration Art of Edward Gorey

As the Society of Illustrators celebrates the centenary of Edward Gorey’s birth, we look back at t...

London Mithraeum is the perfect space for Manders’ three new yet timeless works. Before the openin...

At the opening of his first public exhibition, Nat Faulkner, winner of the Camden Art Centre Emergin...

Richard Hawkins: Potentialities

Bringing together early religious imagery, ritual performance, painting and AI, Hawkins taps into th...

Reflections. Picasso x Barceló

Ceramics by Picasso are juxtaposed with works by Miquel Barcelo, one of Spain’s leading contempora...

Award winners Roman Manfredi and Sayuri Ichida bring lost and overlooked communities into view, with...

Dom Sylvester Houédard: dsh* and EE Vonna-Michell – Henri Chopin: To Ra...

This exhibition draws together the concrete typestracts of Houédard with a stunning film by Henri C...

Organised in conjunction with the Abu Dhabi Music & Arts Foundation, this extensive exhibition at Se...

What characterises a monument? Mass? Authority? Glory? And what should be its destiny? If inspiring,...

Including works by Bert Hardy and Oscar Marzaroli to Alan Dimmick and Iseult Timmermans, this exhibi...

Kira Freije: Unspeak the Chorus

Kira Freije has created 26 new works for this show, life-size figures imbued with a rich and often ...

The Frick Collection: The Historic Interiors of One East Seventieth Street...

Celebrating the newly renovated Frick Museum, this treasure of a book takes the reader on a room-by-...

The artist explains feeling that she belonged neither to the Vietnamese community of her heritage or...

A thought-provoking exhibition of archival material and related artworks celebrating the centenary o...

From river pollution to radioactive waste, through aquatic atmospheres and mythic journeys, Emilija ...

This magnificent exhibition includes bold posters, woodcuts, portraits and still lifes, but it is Wi...

Through painting, sculpture and film, three international artists ask us to reflect on ecological de...

Dana Awartani: Standing by the Ruins

Using traditional craft techniques, Dana Awartani traces the destruction of cultural heritage sites ...

The loss of an icon is ever of great note but that the iconoclast architect Frank Gehry’s passing ...

Luigi Ghirri: Polaroid ’79-’83

Luigi Ghirri’s spell using Polaroid cameras takes us on an imaginary adventure, with leading clues...

A groundbreaking exhibition turns the way we think about sculpture on its head. Every object has its...

Photographer Merlin Daleman talks about how his new photo book, Mutiny, captures the backstory of th...

Three seductive, spellbinding films demonstrate the Uzbek artist and film-maker Saodat Ismailova’s...

German painter Gerhard Richter enchants, astonishes and unnerves in this compendious retrospective, ...

Karimah Ashadu’s three films may aim to give a voice to marginalised men in the former British col...

Playing with Fire: Edmund de Waal and Axel Salto

The artist and author Edmund de Waal has curated the first major exhibition of the Danish ceramicist...

Women of Influence: The Pattle Sisters

Seven sisters made their mark on Victorian art and culture and deserve to be far more than just dist...

Anindita Dutta: The Shadows of Duality

Shifting from her usual clay to recycled shoes, animal hides, fur, fabrics and more, Anindita Dutta ...