Dana Awartani: Standing by the Ruins, installation view, Towner Eastbourne. Photo: Rob Harris.

Towner Eastbourne

29 November 2025 – 25 January 2026

by BETH WILLIAMSON

Palestinian Saudi artist Dana Awartani’s exhibition at Towner Eastbourne is an exquisitely crafted cartography of cultural cleansing. A powerful picture of the loss of cultural heritage, Standing by the Ruins presents a reflective account of the destruction caused by conflict within the Middle East. It is a quietly authoritative companion to her film and installation being shown at the nearby Goodwood Art Foundation as part of the exhibition Erasure. In that work, I Went Away and Forgot You. A While Ago I Remembered. I Remembered I’d Forgotten You. I Was Dreaming (2017), Awartani merges contemporary art and craft techniques in a way that is supremely sensitive to cultural preservation. Here at Towner that same sensitivity is palpable in work that spans painting, installation and textiles. Places that have been abandoned, destroyed or even entirely vanished are brought sharply back into focus through the artist’s use of methods and materials in a fashion that seems to comfort and heal.

Dana Awartani: Standing by the Ruins, installation view, Towner Eastbourne. Photo: Rob Harris.

Standing by the Ruins, named after an ongoing series of floor installations and paintings, presents the viewer with three compelling themes – remembrance, healing and forgetting. For Awartani, the process and practice of making is equally as important as the finished work and so traditional crafts techniques, such as adobe building methods and darning, are brought to the fore through her work with skilled artisans and locally sourced materials. The historical and visual references to Islamic and Arab art-making techniques mean that Awartani’s contemporary and politically charged practice remains rooted in traditional artisanal craft, both techniques and materials, meaning its relevance to cultural histories is never in question.

Dana Awartani: Standing by the Ruins, installation view, Towner Eastbourne. Photo: Rob Harris.

Across two adjacent gallery walls are six framed studies of a variety of Ottoman-influenced patterns painted in natural pigments on handmade cotton rag paper from Jaipur in India. The studies accompany Standing by the Ruins III (2025), Awartani’s latest iteration of such floor-based works. It recreates the detailed Ottoman-influenced floor design from Gaza’s Hammam al-Sammara – one of the oldest bathhouses in the region and now destroyed by Israeli bombardment. Each individual brick in the installation was made in a longstanding collaboration with craftsmen who work with adobe restoration in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The handmade bricks are dried in the sun, but in Awartani’s installation the binding agent is omitted, suffusing the work with both strength and fragility.

Let Me Mend Your Broken Bones, 2023. Installation view, Dana Awartani: Standing by the Ruins, Towner Eastbourne. Photo: Rob Harris.

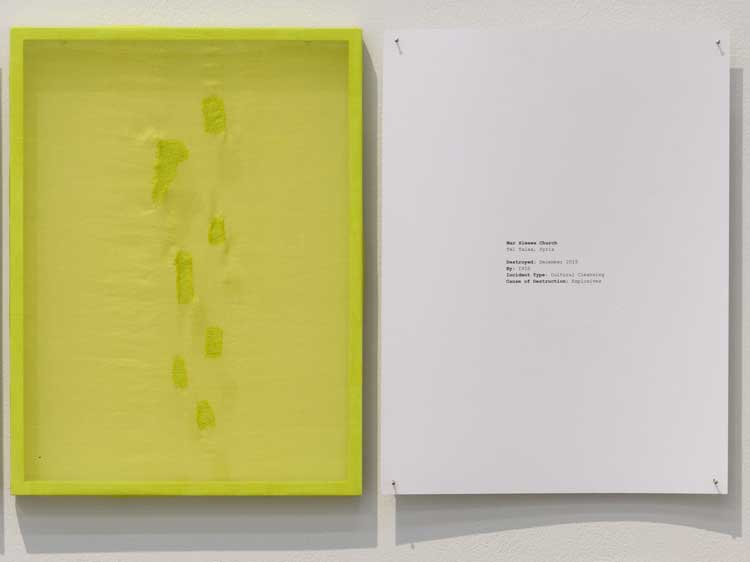

The remaining two walls of the gallery are lightly occupied with a series of works titled Let Me Mend Your Broken Bones (2023), in which Awartani continues her commentary on the destruction of Middle Eastern cultural heritage. Each work references a specific location in Syria that was destroyed between 2012 and 2016. The artist’s use of natural materials and medicinal herbs and spices gestures to the ethical and ecological conditions of the work’s production. The work also exists to deflect mental and technological colonial violence through its underlining of artisanal craft production and local medicinal knowledge.

The small scale and fragility of these works belie the gravity of the issues they address. Each panel is carefully constructed from naturally dyed silk, handmade in Kerala , stretched across a small wooden frame. Their treatment is intricately concerned with care and healing since the fabric is treated with herbs, spices and plants that are imbued with medicinal functions in South Asian and Arab cultures. These include turmeric, holy basil, henna, jasmine, lotus and pomegranate. Awartani ruptures the stretched fabric, with each tear corresponding to a site of destruction. She then invited an expert darner to repair the rupture. She says: “It’s a way for me as an individual to mourn the loss of my own heritage … the act of repairing something through the act of darning was my own way of mourning that loss.”

Let Me Mend Your Broken Bones, 2023. Installation view, Dana Awartani: Standing by the Ruins, Towner Eastbourne. Photo: Rob Harris.

These poignant works are each hung with a descriptive note explaining details of the incident concerned. A darned rectangle of silk, dyed blood-red with medicinal herbs, represents the destruction of Saint Takla Monastery in Maaloula, which, the accompanying artist’s text states, was the subject of an al-Qaida attack in April 2012, such that arson, vandalism and looting left it destroyed. A similar piece of darned lime-green silk represents the explosion when Mar Odisho Church in Tel Tal was blown up by Isis in an act of cultural cleansing in April 2015. Further cultural cleansing is evidenced in an acid-yellow piece of silk representing the explosion when the al-Nusra Front destroyed the Mausoleum of Imam Nawawi in Nawa, Deraa, in 2015. The litany of destruction continues. The Bab al- Nasr area in Aleppo was destroyed by fire and shelling in July 2014 during the civil war. The accompanying orange silk, with its multiple tears and repairs, represents this tragedy. Another stretched section of orange silk, repaired in eight places this time, represents another tragic event, that of the cultural cleansing of Mar Yun an Church in Tel Jazira in Syria in December 2015, again by Isis. These are just some of the series of colourful panels, ruptured and repaired in act of mourning by the artist.

The tears in each work correspond to the shadows of physical violence inflicted on the particular building by Islamic fundamentalists. The artist sourced her information from the Antiquities Coalition so that accompanying texts follow information from this catalogue of vulnerable heritage sites and every detail is precise – the exact time and location of each traumatic event, its cause and the group claiming responsibility. Repairing and respecting objects, including buildings, is not always possible, particularly in places of conflict. Awartani’s answer is to trace the destruction with thread, to darn it whole again through a collective act of healing. Mending the holes in this way becomes a meditative process and an act of mourning and commemoration. Choosing not to forget such violent and traumatic acts through such tender and fragile processes and works is in itself miraculous.