Christopher Le Brun, Phases of the Moon IV, 2024. Installation view, Cosmos: The Art of Observing Space, Royal West of England Academy, 2026. Photo: Alastair Brookes.

Royal West of England Academy, Bristol

24 January – 19 April 2026

by DAVID TRIGG

The breathtaking grandeur of the cosmos has captured the imaginations of artists and scientists for centuries, inspiring awe, wonder and an insatiable desire to understand its mysteries. Born from artist and curator Ione Parkin’s longstanding interest in the confluence of art and astronomy, this expansive exhibition at the Royal West of England Academy mingles scientific enquiry with the artistic imagination to consider the myriad ways in which artists past and present have responded to phenomena beyond the Earth’s atmosphere. From representations of celestial bodies and distant star systems to imagined interstellar landscapes and invisible cosmic particles, the show’s works reflect on the vast complexities of space while spotlighting how astronomical science has inspired creativity and how artistic expression has in turn played a role in scientific study.

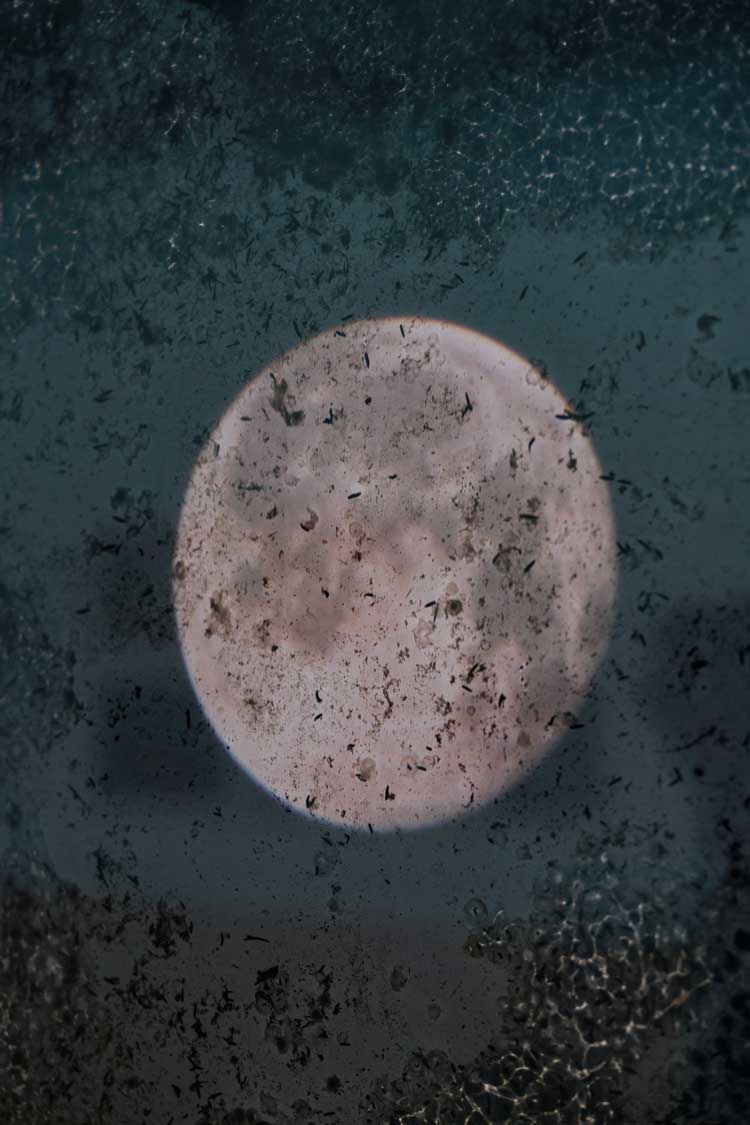

Susan Derges, Full Moon Spawn, 2007. Installation view, Cosmos: The Art of Observing Space, Royal West of England Academy, 2026. Photo: Alastair Brookes.

As our nearest celestial neighbour, the moon is the subject of numerous works, several of which consider its influence on terrestrial life. In her large photograph Full Moon Spawn (2007), Susan Derges presents its luminous form surrounded by clouds of frogspawn, suggesting a pond’s-eye view of the night sky and speaking to the intimate connection between lunar cycles and the rhythms of the natural world. Christopher Le Brun’s enormous 12-panel painting Phases of the Moon IV (2024) fills the main gallery’s end wall. The semi-abstract composition charts the moon’s trajectory across the night sky, its gentle glow partially shrouded by vigorous layers of vertical and horizontal brushstrokes. Le Brun’s lyrical vision is contrasted with Annie Cattrell’s glitzy sculptural approximation of the lunar surface; based on lunar data from Nasa, the wall-mounted slice of moonscape renders the crater-pocked regolith in Jesmonite and glistening silver leaf.

Annie Cattrell, Being There, 2025. Photo: Alastair Brookes. Installation view, Cosmos: The Art of Observing Space, Royal West of England Academy, 2026. Photo: Alastair Brookes.

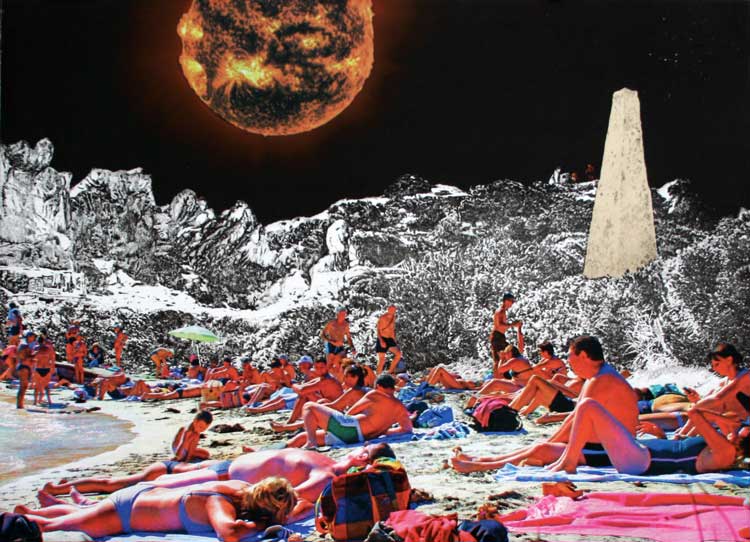

Susan Eyre, Sun Factor, 2015. Screenprint on aluminium. © the artist.

The massive, blazing star at the centre of our solar system has inspired several pieces, from Susan Eyre’s apocalyptic photo-collage Sun Factor (2015), in which the sun is presented as a menacing fireball turning beachgoers as red as lobsters, to Janette Kerr’s enchanting pinhole photographs that chart its trajectory across the skies of Iceland, Greenland, Scotland and England. The sun’s apparent daily path is, of course, caused by the Earth rotating on its axis. Simon Hitchens records this movement in his series Orbit (2024-25), created over the course of a year. For each of the 12 drawings, he placed a stone on a sheet of paper and, working from dawn to dusk, repeatedly traced the contour of its moving shadow. These records of celestial temporalities are all surprisingly different, reflecting the shifting position of the Earth across the months.

Simon Hitchens, Passage, 2026. Installation view, Cosmos: The Art of Observing Space, Royal West of England Academy, 2026. Photo: Alastair Brookes.

Hitchens’s accompanying black concrete sculpture, Passage (2026), is a three-dimensional representation of a noon shadow cast by an ancient boulder. At one end of the enormous wedge-like form is an inverted impression of the rock, a highly textured void from which diagonal striations jut downward like rays of light being sucked into a black hole. The sculpture’s otherworldly appearance suggests a hunk of space rock and, nearby, Ben Rowe’s geometric sculpture Chicxulub (2025) references the asteroid that is widely believed to have wiped out the dinosaurs 66m years ago. Made with multiple triangular brass segments, it reimagines the enormous asteroid impact crater on the edge of the Yucatán peninsula in Mexico as a metallic, undulating topography.

Johanna Love, Residua I, 2025. Installation view, Cosmos: The Art of Observing Space, Royal West of England Academy, 2026. Photo: Alastair Brookes.

Elsewhere in the show is an actual meteorite – a fragment of the 700kg Krasnojarsk pallasite, which in 1794 became the first extra-terrestrial object to be recognised by science. While many such objects have naturally found their way to Earth, others have been collected by humans. In 2020, samples were collected from the near-Earth asteroid Bennu by the US spacecraft OSIRIS-REx. Scientists believe that similar asteroids may have been responsible for first delivering the basic building blocks of life to Earth. In her graphite drawing Residua I (2025), Johanna Love depicts a tiny dust particle from Bennu as if it were a huge hunk of rock, a reminder that just as the microscopic sometimes mirrors the macroscopic, so, too, can extraterrestrial objects appear like those of terrestrial origin.

Several of the show’s artists have collaborated with scientists, incorporating scientific data into their work. Melanie King’s Pillars of Creation (2025) from her photographic series In Praise of Raw Data (2017-present) examines the mediated nature of astronomical imaging by highlighting the beauty of unintended technical flaws that can occur in space telescopes. This image of deep space is dotted with six-pointed stars – optical artefacts that, despite their aesthetic appeal, would normally be corrected before public consumption.

Ian Chamberlain,Tranmission IV, 2015.RWA Alastair Brookes KoLAB Studios. Installation view, Cosmos: The Art of Observing Space, Royal West of England Academy, 2026. Photo: Alastair Brookes.

Other artists highlight the continually evolving nature of astronomy. Lynda Laird’s An Imperfect Account of a Comet (2022) spotlights the work of the pioneering astronomer Caroline Herschel, who, in the 1780s, documented hundreds of stars that she noticed were missing from the British Star Catalogue. Laird’s floor-bound lightbox installation of glass slides features a selection of Herschel’s missing stars and pays tribute to the women whose groundbreaking contributions to astronomy have been historically overlooked and undervalued.

Highlighting how far astronomy has come in the last few hundred years, the show includes several historical objects from the early days of astronomy, including celestial maps, a pocket sextant from the 1790s, late-18th-century lunar drawings by John Russell and solar eclipse drawings made between 1882 and 1908 by William H Wesley, which delightfully resemble geometric abstractions. Surprisingly, no telescopes are included, but Ian Chamberlain’s research into the evolution of telescope design is represented in his technically impressive etchings depicting the utilitarian architecture of the Royal Observatory Greenwich and the Lovell telescope at Jodrell Bank.

-credit-RWA-Alastair-Brookes-KoLAB-Studios.jpg)

Rachael Nee Coincidence! 2025. RWA Alastair Brookes KoLAB Studios. Installation view, Cosmos: The Art of Observing Space, Royal West of England Academy, 2026. Photo: Alastair Brookes.

Rachael Nee’s Coincidence! (2025) is both sculpture and scientific instrument. With cables running up and down its length, the antenna-like structure has a heart of electronics that somehow is able to detect muons – micro-physical particles created when cosmic rays from space collide with atoms in Earth’s upper atmosphere. When a muon passes through the gallery, the work responds with light, sound and a cryptic “muonic message” displayed on an LCD screen. “You will feel observed by the absence of a distant star,” reads one of them. Nee’s work demonstrates how the cosmos is not just about outer space phenomena, it is also here, on Earth; we are not simply observers of the universe, we are a part of its activity.

Michael Porter, Impossible Landscapes, 2023-5. © the artist.

While hard science informs many works here, some artists let their imaginations soar. Michael Porter’s small series of paintings, Impossible Landscapes (2023-25), have a science-fiction quality, depicting imagined planetary bodies amid clouds of interstellar dust. Parkin, the show’s curator, has been collaborating with astronomers and cosmologists for nearly a decade, though her spectacular canvases evoking billowing gases and the turbulent motion of super-heated plasma are painterly inventions. Similarly, the puckered and furrowed surfaces of her mixed-media images, Speculations on Planetary Surfaces 1-6 (2025), imagine geological samples from sections of undiscovered planets. Gillian McFarland invites chance into her stunning blown-glass sculptures, mixing different chemicals with the molten material to produce fantastical globes coloured with mesmerising swirling patterns. The spheres resemble distant planets and are suspended from the ceiling to resemble a miniature solar system.

Anna Gillespie, Stars Through Bars, 2025. RWA Alastair Brookes KoLAB Studios. Installation view, Cosmos: The Art of Observing Space, Royal West of England Academy, 2026. Photo: Alastair Brookes.

Anna Gillespie’s small and delicate sculpture Stars Through Bars (2025) is one of the few pieces to represent the human presence in relation to the vastness of the heavens. Two fragile figures contained within a rusty bird cage gaze upwards, as if pondering their existence. In a compelling show brimming with cosmologically inspired artworks, it is a poignant and humbling image; a reminder that, despite the amazing advances of astronomical science, the cosmos is still replete with mysteries that, for now at least, remain far beyond the reach of human comprehension.