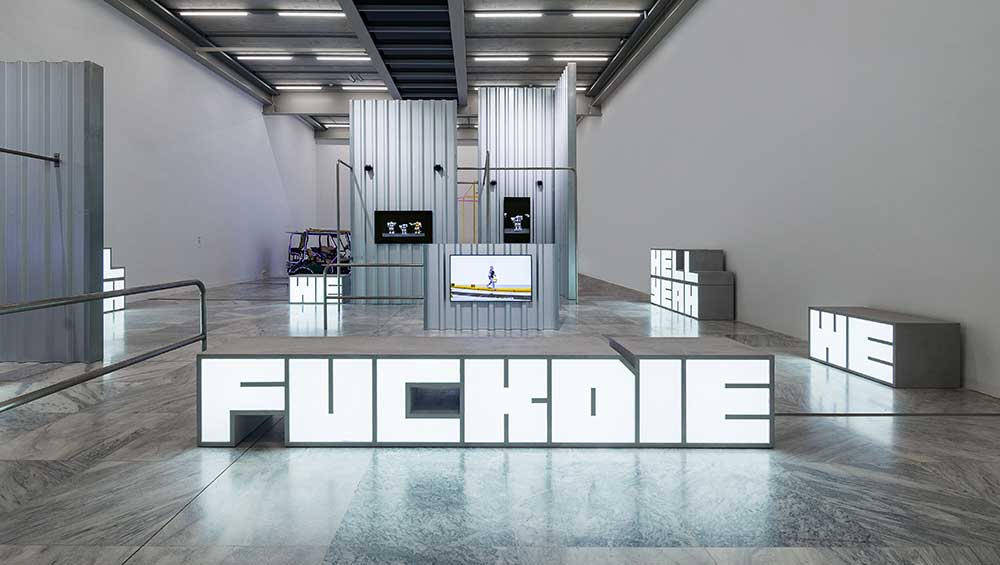

Hito Steyerl, Hell Yeah We Fuck Die, 2016. Video installation (Edition 6/7). Installation view, Hito Steyerl: Humanity Had the Bullet Go In Through One Ear and Out Through the Other, 2025. MAK Contemporary © kunst-dokumentation.com / MAK.

Museum of Applied Arts (MAK), Vienna

25 June 2025 – 12 April 2026

by JOE LLOYD

“Humanity,” wrote the Austrian essayist Karl Kraus in his unstageable 15-hour play The Last Days of Mankind, “had the bullet go in through one ear and out through the other.” He was writing in the aftermath of the first world war. The war that would end all wars turned out to be anything but, and Kraus’s words remain penetrating in their implications of a humanity seemingly unable to learn from its mistakes. More than a century later, the German artist Hito Steyerl has borrowed them for her exhibition at Vienna’s Museum of Applied Arts (MAK). Her perspective is no more optimistic – although, like Kraus’s satire, it is leavened with wit.

Artists can play many parts. Once they were courtiers, cartographers, craftspeople. Then they became chroniclers of contemporary life, showmen and -women, theorists, humorists, political activists and documentarians. Steyerl is the paradigm example of the artist-as-intellectual. She studied film-making and has a PhD in philosophy; her career as an artist is shadowed by a substantial body of writing, perhaps most famously the essay collection Duty Free Art: Art in the Age of Planetary Civil War (2017). That same year, Art Review declared her the most influential figure in the art world. Though that era may have represented a peak in her prominence, Steyerl has continued making penetrating films and installations.

Hito Steyerl, Mechanical Kurds, 2025. Video installation. Courtesy of Hito Steyerl, Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York, Esther Schipper, Berlin / Paris / Seoul. © Hito Steyerl. Video stills: © Hito Steyerl, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2025.

Steyerl’s works from the 2000s and early 2010s attempted to make sense of the mass proliferation of images created by new media and technology. She argued for the potential of grassroots image-making to subvert society and warned against the difficulty of maintaining privacy in our surveillance culture. She has also turned her gaze on the art world, investigating corporate sponsorship and dubious patrons, always with an eye on wider systems. Recently, Steyerl has turned her penetrating gaze on to the technology of the day. The City of Broken Windows (2018) explored the ramifications of teaching AI to comprehend the sound of smashing glass, while her most recent book, Medium Hot: Images in the Age of Heat (2025), identified, among other things, how marginalised communities are being trampled by the inexorable rise of the data industry.

Hito Steyerl, Mechanical Kurds, 2025. Video installation. Courtesy of Hito Steyerl, Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York, Esther Schipper, Berlin / Paris / Seoul. © Hito Steyerl. Video stills: © Hito Steyerl, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2025.

At MAK, Steyerl has presented a new work, Mechanical Kurds (2025), that continues these concerns. It is paired with 2016’s more visceral Hell Yeah We Fuck Die, providing a bridge between almost a decade of Steyerl’s practice. To enter the exhibition is to jump suddenly from one architectural milieu to another. MAK’s main courtyard is a warm-hued 19th-century palace, covered in neo-Renaissance decorative paintings. Steyerl’s exhibition is off to the side, in a white-walled room with exposed metal ceiling beams. The courtyard’s calm is replaced by pulsating techno. Phrenetic videos are mounted on sleek corrugated steel sheets. Illuminated letters are strewn across the floor, large enough to serve as benches. The biggest of these units reads “FUCK DIE”, the two words compounded into a single nihilistic curse.

Hito Steyerl, Hell Yeah We Fuck Die, 2016. Video installation (Edition 6/7). Installation view, Hito Steyerl: Humanity Had the Bullet Go In Through One Ear and Out Through the Other, 2025. MAK Contemporary © kunst-dokumentation.com / MAK.

This earlier work, all smiling and colloquial as it bombards the senses, remains as overwhelming today as when I first saw it at Skulptur Projekte Münster in 2017, where it was housed inside a brutalist bank, or in 2024 when I encountered it again inside the haunted baroque sala of the Castello di Rivoli. It is named for the five most common words in the English language pop charts of the 2010s. It features two video works. One, presented over three screens, homes in on robots used to save people in disaster zones. What we see, however, are scientists appearing to physically abuse their androids, in the name of training. The metallic backdrop becomes a sort of militarised athletics ground.

Hito Steyerl, Hell Yeah We Fuck Die, 2016. Video installation. © Hito Steyerl, Hell Yeah We Fuck Die, 2016, Loan LBBW Collection. Video stills: © Hito Steyerl, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2025.

The second film component of the work is ostensibly very different from this dystopian futurism. Robots Today includes documentary footage of the Kurdish towns of Diyarbakir and Cizre in the aftermath of street fighting. There are empty streets, battered buildings and cats crawling over debris. Steyerl juxtaposes this material with an account of Ismail al-Jazari, a medieval artist and inventor famous for his handbook for creating programmable automata, and largely unanswered questions to Siri about robots and destruction. Floating between these modes, Steyerl’s film is suggestive rather than insistent, encouraging the viewer to make their own connections between Al-Jazari’s proto-robots and the weapons used in present-day suppression and war.

The new work, Mechanical Kurds, uses a similar technique. It also references another famous automaton, albeit a phoney: the Mechanical Turk, an 18th-century chess-playing machine operated by a hidden dwarf, that today gives its name to an Amazon service that uses low-paid labour for click work. The largest part of Steyerl’s film follows Kurds in a refugee camp who had to categorise images from military camera footage, which was then used to train AI image recognition models, which would be in turn used by driverless cars and drones. They were not informed of the purpose their work would serve. One almost wistful segment sees some of them speculate on it.

Hito Steyerl, Mechanical Kurds, 2025. Single screen installation, 13 min. Installation view, Hito Steyerl: Humanity Had the Bullet Go In Through One Ear and Out Through the Other, 2025. MAK Contemporary © kunst-dokumentation.com / MAK.

They also describe the streets they analysed, which they feel variously resemble the US, Switzerland, China and Germany. This is when things get strange. The film ends up in an AI-generated city square with an oversized streetlamp and what looks like a steampunk interpretation of Berlin’s TV Tower. Golf buggies – which also provide seating at MAK – spin around this square with reckless abandon. Then a drone appears. The vehicle explodes, and the film cuts to a Kurdish journalist describing a drone attack in which his two fellow passengers were killed. The tonal whiplash is immense and devastating.

Hito Steyerl, Mechanical Kurds, 2025. Single screen installation, 13 min. Installation view, Hito Steyerl: Humanity Had the Bullet Go In Through One Ear and Out Through the Other, 2025. MAK Contemporary © kunst-dokumentation.com / MAK.

These initially disconnected segments – which also include an AI-generated traditional song and bodies impossibly dancing in the sky – cohere to provide an essay on the way human labour feeds AI that can later be turned to the destruction of humans. Steyerl makes visible the imposition of digital classification systems on to reality, and the continuing erasure of the boundaries between real and digitally generated images. She also makes clear the growing entanglements between human labour and that done by computer programs, which which some companies seek to conceal even from those doing the works. In her 2013 breakthrough work How Not to be Seen: A Fucking Didactic Educational .MOV File (2013) Steyerl drolly investigated the – very limited – ways in which we can disappear from digital surveillance. In 2026, there is nowhere left to disappear to.