Tetsumi Kudo. Microcosms, installation view, Hauser & Wirth London, 2026. © Hiroko Kudo, the Estate of Tetsumi Kudo / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP Paris 2026. Courtesy Hiroko Kudo, the Estate of Tetsumi Kudo and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Eva Hurzog.

Hauser & Wirth, London

5 February – 18 April 2026

by JOE LLOYD

What are we looking at when we look at Work-P (2019-2023), an artwork on a panel by the venerable Japanese artist Takesada Matsutani (b1937)? A translucent white film sits atop a teeming field of black ink, slightly off centre. Beneath this glossy, creased surface there is a ring of black encircling one of white, then a black core. Is this an eye, staring out at us? Or is it simply an arrangement of material on a surface? Matsutani seldom makes it easy to tell. His new exhibition at Hauser & Wirth London features several works that incorporate this same slick material. One resembles a penis poking out from an indigo blob, another a fingerprint floating on two spindly legs. But questions of what, if anything, these works depict are less important than questions of how Matsutani has shaped this odd material, which remains fixed in place despite appearing like an oozing liquid.

Takesada Matsutani, Abstrait 抽象 La Boverie, Liege, Belgique, 2024. Vinyl adhesive, acrylic on canvas mounted on panel, 184.5 x 184.5 x 3.5 cm (72 5/8 x 72 5/8 x 1 3/8 in). Photo: Nicolas Brasseur.

Matsutani was born in Ōsaka in 1937. After a youth marked by bouts of tuberculosis, he began his artistic career as a figurative painter. At the time, the cutting edge of Japanese art was represented by the Gutai Art Association. In Gutai, its leader Jiro Yoshihara declared: “The human spirit and matter shake hands with each other while keeping their distance.” This often manifested in messy, madcap performances. Shozo Shimamoto fired paint bombs from a cannon, Saburo Murakami ran through giant sheets of paper, and Kazuo Shiraga stripped to his underwear and crawled around a patch of sloppy mud. The young Matsutani was not convinced. “In all honesty, I did not like what they were doing and thought: ‘This is not art. It’s blasphemy.’”

Takesada Matsutani, Work - P, 2019–23. Vinyl adhesive, ink on panel, 190 x 190 x 12 cm (74 3/4 x 74 3/4 x 4 3/4 in). Photo: Nicolas Brasseur.

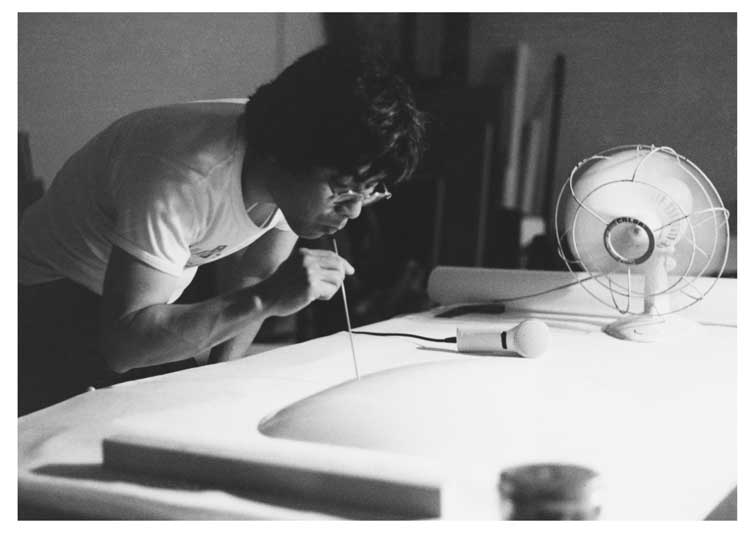

Nonetheless, he took on board Gutai’s interest in novelty, and particularly in finding new materials with which to create art. In 1960, he exhibited canvases covered in soil and cement at one of the group’s exhibitions. But he found himself shoved in the corner. His breakthrough moment came a few years later. Inspired by watching blood samples under a microscope, he sought a material that would let him create flowing, organic rooms. The answer came with polyvinyl acetate glue (also known as vinyl glue or PVA), a strong industrial adhesive. He began to throw it at the canvas, creating a thin diaphanous membrane. Matsutani initially left this material to dry in the wind, creating dripping stalagmite-like forms. Seeking greater control, he soon switched to using hairdryers and fans. This let him stretch and blow his material, varying its shape and thickness.

Takesada Matsutani exhaling air into vinyl adhesive, 1981. © Takesada Matsutani. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

Many of the resultant works feature forms that resemble the bumps and orifices of the human body – eyes, mouths, breasts, genitals. The spectre of Lucio Fontana looms large over these protrusions, some of which have slashes reminiscent of the Argentine Italian’s cuts. It was this work that saw Matsutani accepted as an official member of Gutai. He continues to explore this material today, but his approach has evolved over time. While the early works saw the vinyl glue leap off its canvases, the recent works shown at Hauser & Wirth generally have it pressed close. Some interpolate simple objects such as rope and a wooden stick, whose three-dimensionality contrasts with this flatness.

Matsutani has recently started dyeing the glue purple and applying it to canvases painted with white acrylic. The glue comes to resemble a shimmering puddle of water wrinkled by the wind. Matsutani’s purple compositions look like life forms viewed in a petri dish. They have a casual presence, compounded by the way some pieces are leaned against the wall as if the artist has just left them there. The exhibition also contains some sculptural works. Extension 1 (2024) is a small totem-like object made of homely materials including string, cardboard and ink-splattered pieces of wood. It could be an obscure household tool.

Takesada Matsutani , Stream 83-97, 1983–97. Graphite pencil on canvas, with dilution, 215 x 1000 cm / 84 5/8 x 393 3/4 in. Photo: Stefan Altenburger.

The exhibition also introduces a different strand of Matsutani’s career. After moving to Paris in 1966, he spent a decade experimenting in printmaking, sculpture and hard-edge abstraction. Then, encouraged by his wife and fellow artist Kate van Houten and mindful of the limited resources available to him, he returned to using graphite pencils. Stream-2 (1978), which rolls across two walls of the Hauser & Wirth gallery, features a hard-drawn black bar stretched across almost 10 metres (33ft) of paper, until it appears to dissolve. It is both beautiful and intimidating, a record of hours of monotonous and painstaking labour. “Over time,” writes curator Mika Yoshitake in the upcoming Hauser & Wirth publication In the Studio: Takesada Matsutani, “the accumulation of marks creates both a physical sheen and a visual depth, evoking the flow of water in motion or the endless passage of time.” While his vinyl works suspend something that appears to be moving, the Streams seem to create movement from a still mark.

Takesada Matsutani, Propagation 25-B, 2025. Vinyl adhesive, acrylic, wooden stick on canvas mounted on panel, 162 x 130 x 6.4 cm (63 3/4 x 51 1/8 x 2 1/2 in). Courtesy Private Collection. Photo: Nicolas Brasseur.

Alongside Shifting Boundaries, Hauser & Wirth is presenting Microcosmos, an exhibition of Tetsumi Kudo (1935-90), Matsutani’s contemporary. Kudo was also born in Ōsaka and also moved to Paris, where Matsutani made his acquaintance. At first glance, their practices could hardly be more different. Many of the works in Microcosms consist of garishly coloured pet shop cages populated by, among other things, scrap materials, disembodied fragments of rotting human flesh, artificial flowers and hideous grub-like creatures that variously crawl, float, hang and power hamster wheels. These pupae bear an unmistakable resemblance to penises. Human Bonsai – Freedom of Deformity – Deformity of Freedom (1979) does not bother with innuendo: here are four rotten phalluses sprouting from soil like flowers, bound and gagged by metallic roots. One of them secretes a sticky substance.

Tetsumi Kudo, Souvenir‚ La Mue - For Nostalgic Purpose - For Your Living Room, 1967. Acrylic on plastic flowers and mixed media in painted cage, 34.9 x 38.9 x 25.1 cm (13 3/4 x 15 3/8 x 9 7/8 in). Photo: Thomas Barratt.

Matsutani writes in the gallery’s journal, Ursula: “For Kudo, physical impotence is a metaphor for society itself being made powerless. In his recriminations of society, the mouldy phallus also exemplifies human debilitation.” The encaged grubs stand for humans trapped in systems beyond their control. The cage work Coelacanth (1970) features food trays stuffed with painkillers, fodder to anaesthetise the human captives. Kudo’s world is a corrupted one, where we are grotesque sacks of meat impotent against wider mechanisms of control. His art is powered by these ideas, while Matsutani’s practice is driven by material, aesthetic and the process of creation. And yet there is a curiously affinity between the two – and not just in their propensity to create works that resemble private parts. They each push beyond conventional artistic notions of beauty: for Matsutani by finding an alternative, and for Kudo by rejecting beauty completely. And both capture something of our plastic world, where the synthetic can imitate – or supplant – the natural.