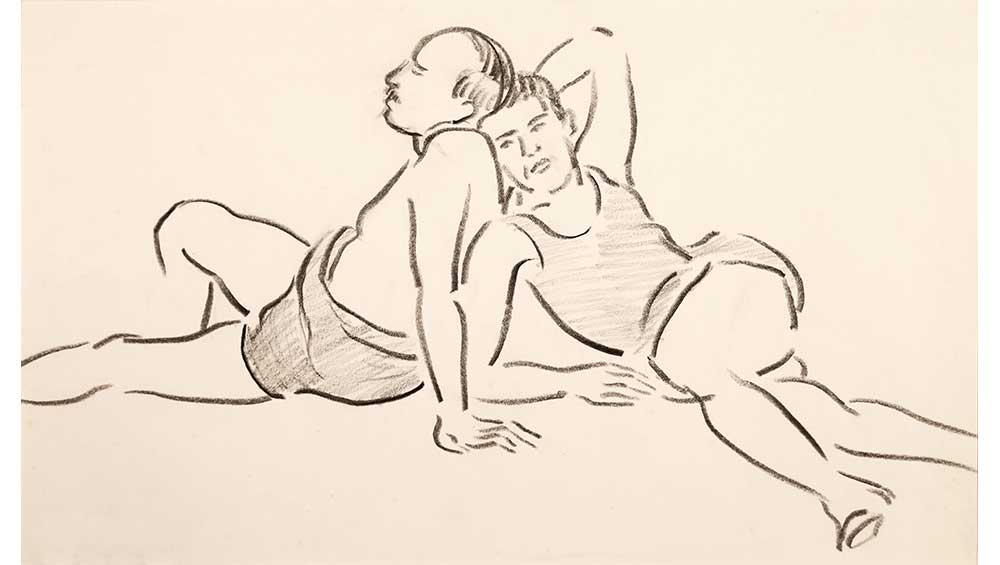

Elsie Barling (1883–1976). Norman Notley and David Brynley, c1930. Pencil on paper. Courtesy of The Ingram Collection and Dorset Museum & Art Gallery.

Dorset Museum and Art Gallery, Dorchester

31 January – 10 May 2026

by ANNA McNAY

They say a picture speaks a thousand words, and that is a notion well borne out by People Watching, a collaborative exhibition between the Dorset Museum and Art Gallery, where it is being held, and the Ingram Collection of Modern British Art. Comprising 50 works of sculpture, painting, drawing and photography, under the very loose categorisation of portraiture (of the past century), it tells not just one story, but myriad stories, as one work speaks to another speaks to another.

The Ingram Collection holds more than 600 works assimilated by the entrepreneur and philanthropist Chris Ingram and is now under the directorship of Jo Baring. Working together with Lucy Johnston of the Dorset Museum and Art Gallery, Baring came up with five themes, which they then dually populated with works, creating an exhibition that Johnston describes as “mouthwatering to install”.

The first work on show, from the home collection, is the earliest: a black-and-white photograph from 1909 of Thomas Hardy on the beach. This firmly locates the mainstay of the stories to be told in Dorset, from whence Hardy came, and where his novels are set. Never before seen in public, this photograph, which is part of the museum’s Hardy archive, shows the author alongside his banker friend Edward Clodd, who made a habit of inviting novelists, critics and historians to his house on the Suffolk seafront. The unselfconsciousness of the subjects, along with their casual ease (despite being dressed in suits, ties and hats!), is something that may be ascertained from nearly all the pictures on display.

Dod Procter, RA (1891-1972), The Golden Girl, c1930. Oil on canvas, 71 x 57 cm. The Ingram Collection. © Estate of Dod Procter. All Rights Reserved 2025 / Bridgeman Images.

The theme for this first section is Leisure and Play, and, for me, this is epitomised by the large painting by Anita Klein, Phone Call in the World Cup (2010), showing a couple at rest on their sofa, husband watching the footie, wife nattering on the phone (although as the label points out, the roles could easily be reversed today in the era of the Lionesses). I love the shape of the woman, curled up with her legs crossed over the arm of the sofa, the cushion beneath her sagging. As with Dod Procter’s The Golden Girl (c1930), also on display, the piece is characterised by its classical, sculptural form.

Robert Duckworth Greenham (1906-1975), On the Beach, 1934. Oil on canvas, 92.5 x 113 cm. The Ingram Collection © Estate of Robert Duckworth Greenham. Photo: John-Paul Bland.

A few works along from the Klein is a splendid art deco painting by Robert Duckworth Greenham, On the Beach (1934), in which one woman is centre stage, yet her story is clearly intertwined with the bodies of those lazing around her. If you were stuck for the starting point to your story, this would be the ideal setting, spilling over with unresolved narratives. With one arm in her coat and one arm out, is she just arriving, or already leaving? Is her hand raised to her hat in greeting, in farewell, or simply as she seeks to disrobe for her leisure time on the sand?

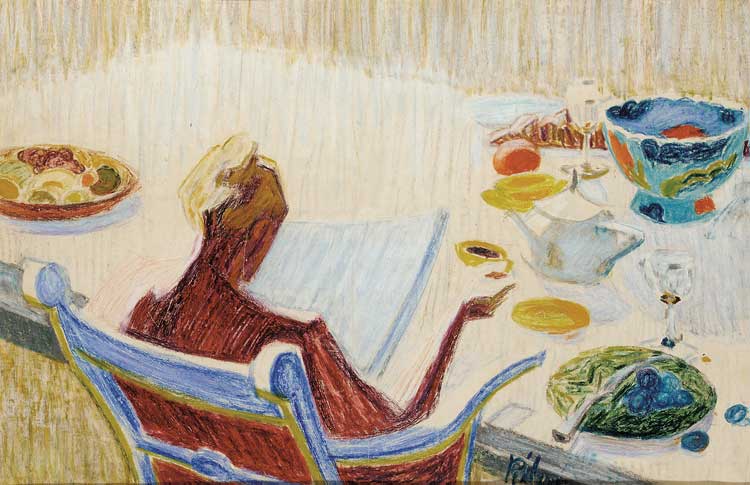

Bridget Riley, RA (b1931), Woman at Tea-table, not dated, coloured crayons and pastel. 48.2 x 73.7 cm. The Ingram Collection © The Artist.

Another piece which cannot escape mention, which Baring describes as “one of the most special works in the Ingram Collection”, is the early Bridget Riley, Woman at Tea-Table (1950s), since it stands out as being so different from her well-known optical artworks. Nevertheless, if one looks at the way her marks are made – all clean, vertical strokes – it perhaps shows an exploration in that direction. “If you go up close,” says Baring, “you start to see those lines and the investigation of colour and air and light and how things move together to create different ways of seeing or the experience of vision.”

Francis Henry Newbery (1855-1946), David Brynley, c1930. Oil on canvas. Courtesy of The Ingram Collection and Dorset Museum & Art Gallery.

A portrait of the Dorset musician David Brynley (by Francis Henry Newbery, c1930) shows him in an outfit gifted by his friend, the painter’s partner, Jessie Newbery (also an artist). This work links with a gorgeous sketch of Brynley and his partner Norman Notley, made with but a few sparse lines by Elsie Barling, once again on a beach. Brynley, Notley and FH Newbery were among the group of artists to settle at Corfe Castle, creating an artist colony in the 1930s.

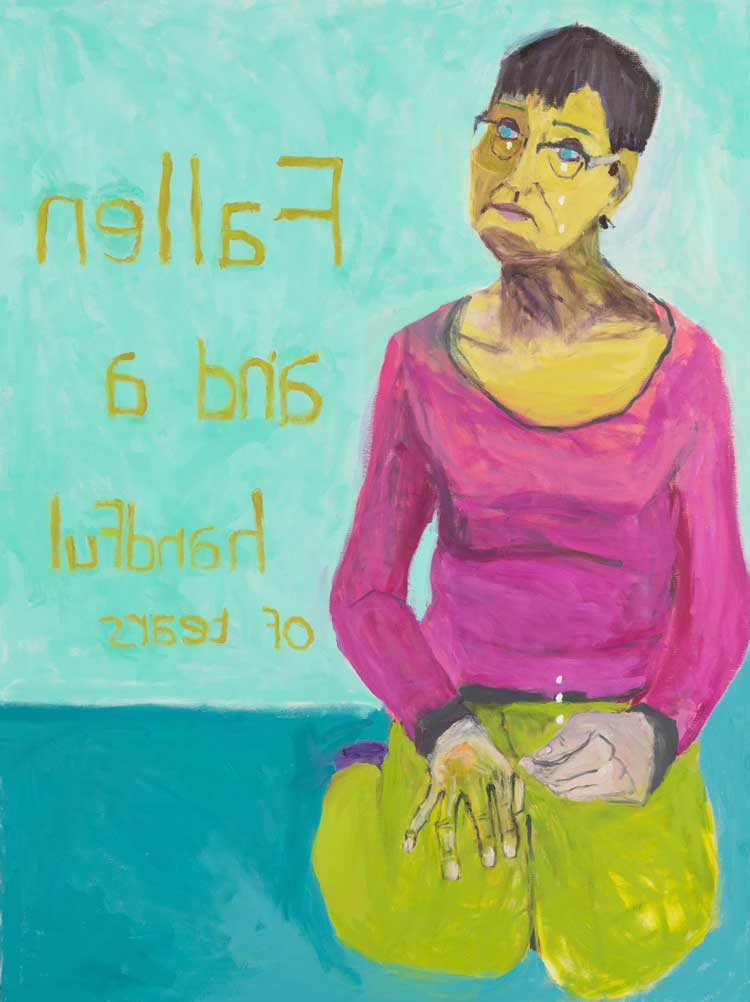

Lucy Jones (b1955), A Handful of Tears, 2013. Oil on canvas, 122 x 91 cm. The Ingram Collection © The Artist. Photo: John-Paul Bland.

Turning the corner into the Self-Portraits section, we are met by a simply wonderful painting by Lucy Jones (A Handful of Tears, 2013). Kneeling dejectedly on the floor, the artist, who lives with cerebral palsy, is forced to take up less than half the canvas, while the words “fallen and a handful of tears” appear in reverse script across the rest of it. Indeed, her eyes are bright with tears, and three pearl-like drops are falling into her hand.

Another piece full of emotion is Billy Childish’s Self-Portrait with Gallows Tattoo (undated), where the deep lines scored into the paint suggest scars and wounds to the human flesh. Nearby, Roger Fry is depicted by a small woodcut (1921), produced by the Hogarth Press (founded by his friends Leonard and Virginia Woolf). The strong lines echo those of Childish. Across from this is a smaller painting by Alan Lowndes, who uses similar mark-making, with impasto strokes of paint, but to very different effect. Friday Night, Mum Combing Jenny (undated) shows a warm and familial scene with a mother tending to the toilette of her two young daughters.

Another small work on show is the watercolour painting Julian (1986) by Mary Fedden, showing her husband (fellow artist Julian Trevelyan) reaching out his hand (for her, or how else might this story go?) in the moonlight. Similarly small, but equally magical, is Dora Carrington’s Iris Tree on a Horse (c1920s), one of her tin-foil paintings, described by Baring as a “kind of jewel”. It shows the actor, poet and celebrated muse in an active role, cropped bob swinging as she gallops apace on her grey steed, “almost like a modern-day Joan of Arc”. Tree loved this portrait so much that she kept it with her throughout her life, propped up on her bookcase. She called it her talisman, like a St Christopher.

Elizabeth Frink, Self-Portrait, 1987. Bronze. Artist © in Elisabeth Frink images courtesy of Tully and Bree Jammet. Courtesy of The Ingram Collection and Dorset Museum & Art Gallery.

In 2020, the museum acquired more than 300 works and associated items by the sculptor Elisabeth Frink, including 31 bronzes. Included here is her only known self-portrait (1987), with sparkling blue eyes, just like those of Jones. Apparently, when the caster was casting the bronze, he looked into Frink’s eyes and said: “You’ve got such blue eyes, such intensity in those eyes, and I’m going to make them good.” I believe he did. Besides this sculpture, there is a drawing of the Moroccan general Mohamed Oufkir (1966), who was in the newspapers at the time for the assassination of the freedom fighter and opposition leader Mehdi Ben Barka. This is being shown here publicly for the first time, alongside the better-known bronze of Goggle Head (1969), the inspiration for which was a photograph of the general. What is intriguing about these pieces, especially in contrast to the self-portrait, is the wearing of dark sunglasses, rendering the eyes invisible. Without the eyes as windows to the soul, one can create only still more fictional narratives.

Sir Stanley Spencer, RA (1891-1959), Portrait of Patricia Preece, 1929. Pencil on paper, 35 x 25 cm. The Ingram Collection © Estate of Stanley Spencer. All Rights Reserved 2025 / Bridgeman Images.

The writer Sylvia Townsend Warner, whose archive the museum also holds, is represented twice in the exhibition: once in a photograph by Cecil Beaton (1928) and once in a small but endearing collage she made several decades later, Woman Working in a Field, Provence (c1958). The latter is drawn from a sketch and a description made in the writer’s travel diaries; the former was taken when she lived in the Dorset village of Chaldon Herring, where there was another artist colony, which centred around the writer Theodore F Powys.

Winifred Nicholson’s Woman Playing a Piano (Vera Moore) (c1930) beautifully captures the movement of the player’s hands by painting only a blur. This contrasts starkly with Ceri Richards’ The Pianist (1946), which similarly captures a sense of flow, but in a fractured, Picasso-esque manner.

What delights Baring is the Ingram Collection’s ability to bring the exhibition bang up to date by including some of its recent Ingram Prize winners, including Alvin Ong (2019), Amy Beager (2022) and Kofi Perry (2023), who really explore and exploit the idea of (self-)portraiture, suggesting, as Baring says, that “maybe it’s not about a direct representation, but about how you create a feeling”.

Gertrude Mary Powys (1877-1952), The Powys Children Reading. Oil on canvas. Courtesy of The Ingram Collection and Dorset Museum & Art Gallery.

Nearly all the works in the exhibition portray the artist themselves, lovers or friends. Some are well-known characters, others less so or unknown. Upstairs, connecting the exhibition with the museum’s (frankly fantastic) permanent collection are four photos on loan from the National Portrait Gallery. These depict Marilyn Monroe (by Baron Sterling Henry Nahum), Tina Turner and Elton John (both by Terry O’Neill) and Marcus Rashford with Adwoa Aboah by Misan Harriman, making Harriman the first black male photographer to shoot a cover for British Vogue in more than a century. Don’t miss the chance to see these, as well as the rest of the collection on display, while at the museum. It is well worth the trip.