Erasure, installation view, Goodwood Art Foundation, featuring mixed-media paintings by Laís Amaral and carved soapstones by Solange Pessoa. Photo: Toby Adamson.

Goodwood Art Foundation, West Sussex

22 November 2025 – 12 April 2026

by BETH WILLIAMSON

This winter season at Goodwood Art Foundation a new exhibition, Erasure, features work by three international artists confronting the destruction of ecological systems and cultural heritage. Work by Laís Amaral, Solange Pessoa and Dana Awartani is presented across two gallery spaces. Set in a tranquil woodland location, these works invite visitors to reflect on issues such as cultural extraction, deforestation and the erasure of histories. The prompt is surely to consider how we might move towards more sustainable and equitable futures for all. Of course, none of this is easy, but the serene and peaceful setting certainly creates an invitation to pause, a moment to reconsider at length issues that can no longer be overlooked.

Laís Amaral, Le maître des arcanes, 2025 and Solange Pessoa, Nihil Novi Sub Sole, 2019–21, installation view, Erasure, Goodwood Art Foundation. Photo: Toby Adamson.

The trio of artists includes two Brazilians: Pessoa, one of her country’s most renowned living artists, and Laís Amaral, a rising star in Brazilian art. In this, her first institutional exhibition in Europe, Amaral is clearly thrilled to be showing alongside, and in dialogue with, work by an artist of Pessoa’s acclaim. She said: “I am very happy and honoured to take part in this exhibition alongside two artists whose works I admire deeply. The sensitive conversations with Ellie [Eleanor Clarke, the curator] were essential in thinking about my work, especially in dialogue with that of Solange Pessoa, who is truly one of the Brazilian artists I admire the most. It has been fascinating to present so many works together for the first time in the UK, bringing together series from different periods, such as Cimento e Água, Gamboa (2023) and Naturezas Radicais (2024), in which I seek to evoke memory and reflect on the ways nature endures despite processes of colonisation and urbanisation.”

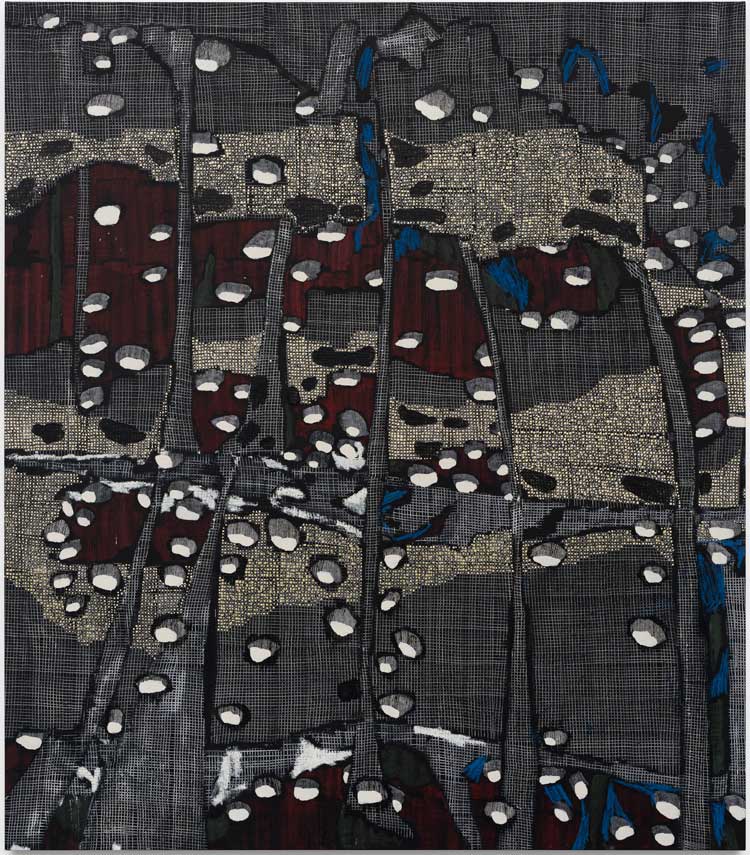

Laís Amaral, Untitled XI, Cimento e água, Gamboa series, 2023. Acrylic and oil pastel on linen, 180 x 160 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Mendes Wood DM, São Paulo, Brussels, Paris, New York. Photo: Hugard & Vanoverschelde.

Amaral presents 17 new and recent paintings, all of which address issues of deforestation, water scarcity and the whitening of Brazilian territories. The parallels are clear – ecological destruction echoes cultural erasure. The self-taught artist uses scraping techniques that gesture to Brazil’s devastated landscapes and to the strength of Afro-Brazilian communities whose cultural practices are rooted in such environments. Amaral was co-founder in 2017 of Trovoa (formed with Carla Santana, Ana Cláudia Almeida and Ana Clara Tito), a collective dedicated to the work of women of colour and those living on the margins of urban space. Together they strengthened, motivated and opened up new perspectives on contemporary art. The paintings are created using tools or objects that Amaral would normally use for personal grooming, such as combs, cuticle pushers and eyebrow tweezers, repurposed as instruments of incision and erasure. Given this association with the body, it is particularly interesting that she insists her paintings are non-figurative, separating them from American and European ideas of abstraction.

Solange Pessoa, Nihil Novi Sub Sole, 2019–21. Carved soapstone sculptures, installation view, Erasure, Goodwood Art Foundation. Photo: Toby Adamson.

Arranged across the gallery floor and out into the landscape, Pessoa’s 33 soapstone sculptures give the sense of being primordial and yet animate. This curious combination of sensations, fused in feeling with Amaral’s paintings, creates a space where the contemporary is called on not only to protect, but also to nurture established territories, existing ecological resources and longstanding cultural practices. In a sense, it creates a space that is almost out of time, suspended at a critical point and allowing for reflection and the potential for action. Pessoa’s sculptures are adorned with motifs from nature (think leaves, flowers and constellations) inspired by the landscape and cultural history of her native Minas Gerais, especially by Barroco Mineiro, the hybrid Baroque style that blended Brazilian and other cultural influences and flourished in the 18th century. Begun in 2014, Pessoa’s soapstone (pedra-sabão) series is also a continuing collaboration of the artist with local stonemasons in Mata dos Palmitos, a series that takes pride in indigenous practices and craftsmanship. This fits with wider trends where artists are turning to craft-based techniques to address big questions, such as ecological decline, in contemporary practice. This embrace of a broader range of materials and methods, in this instance mestizo craft traditions and community knowledge, gives hope for the future.

-Dana-Awartani.jpg)

Dana Awartani, I Went Away and Forgot You, 2017. © Dana Awartani, Courtesy Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Photo: Ron Amstutz.

Over in the Pigott Gallery, Awartani, a Palestinian Saudi artist, presents her mesmerising film installation I Went Away and Forgot You. A While Ago I Remembered. I Remembered I’d Forgotten You. I Was Dreaming (2017). As with Pessoa’s work, contemporary art merges with traditional craft. For Awartani, craft is not a matter of decoration but of staying true to historically situated and locally sourced materials. Her practice is sensitive to ideas of cultural preservation, sustainability and healing.

-Dana-Awartani,-Courtesy-the-Artist-and-Lisson-Gallery.jpg)

Dana Awartani, I Went Away and Forgot You, 2017. © Dana Awartani, Courtesy the Artist and Lisson Gallery.

This 22-minute film and site-specific sand installation is a celebration of Islamic design and sacred geometry. A hand-dyed grid of coloured sand forms a pattern on the gallery floor that is inspired by the Islamic tilework once popular in Arab homes. The film, whose title is taken from Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish’s prose poem Memory for Forgetfulness, precipitates the sadness of “leaving a place that is no longer conscious in your mind and is just a dream”. Through the methodical act of slowly sweeping, Awartani is seen sweeping away an intricately patterned floor in an abandoned house in Al-Balad (Jeddah’s old quarter). Al-Balad’s traditional architecture, as can been observed in the film, was largely replaced with western styles in the mid-20th century so we can see traditional Hejazi features alongside Italianate shutters, symbols of cultural erasure. Through the meditative action of sweeping, Awartani erases the grid of patterned sand, an act of destruction that becomes a ritual for reflection, a responsibility that Awartani does not take lightly. So, too, for us as viewers of this poignant work, these 22 minutes become almost sacred, a space to hold thinking about this built environment and the colonial undertones that led to its erasure. This is a call to protect heritage and humanity.

At a time when the world has already reached a tipping point at which severe environmental damage is irreversible and wars overwhelm entire cultures beyond where they can be fully retrieved, this exhibition gives space for reflection on such devastation and how we might act differently to protect what remains.