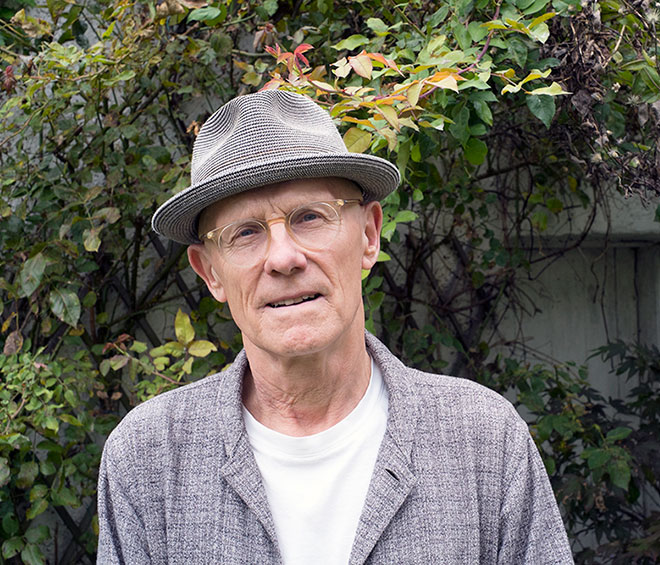

Roger Palmer. © the artist.

by JANET McKENZIE

Refugio – After Selkirk After Crusoe, the recent exhibition of the Glasgow-based artist Roger Palmer, at the Kirkcaldy Galleries on Scotland’s east coast, marked the 300-year anniversary of the first publication of Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe (based in part on the true story of the Scottish sailor Alexander Selkirk). A prescient subject, it enabled the artist to explore colonialism and slavery and their legacies through combinations of media. This month, he is travelling to Johannesburg and Cape Town to launch the publication by Gost Books, London, of Spoor, a series of photographs made in South Africa.

In Palmer’s studio in Glasgow, two projects are in progress in anticipation of their respective centenaries: Partial Eclipse, to mark the 1921 Kronstadt Mutiny against the Bolsheviks’ economic policies in the wake of the Russian Revolution and civil war; and Following the Starry Plough, to mark the Irish war of independence in 1919-21 and the partitioning of Ireland in 1921.

Roger Palmer. Fire, in Refugio - after Selkirk after Crusoe, Kirkcaldy Galleries, 2019. Vinyl, marker pen, acrylic, silver gelatin and inket photographs, 301 x 447 cm. Photo: John C McKenzie.

Janet McKenzie: Can you explain how you came to choose the subject of Robinson Crusoe?

Roger Palmer: Refugio – After Selkirk After Crusoe grew slowly after I found a copy of Robinson, an early 20th-century German children’s book illustrated by Willy Planck, in a secondhand shop in South Africa in about 2015. Having previously exhibited a number of temporary wall works based on engraved drawings, I thought that one illustration in Robinson– an image of two men standing either side of a coastal signal fire – might provide a future starting point. I had already made several silver gelatin photographs of smoke and dust, some of which had been combined with temporary works using recycled book illustrations, so this drawing offered a possibility for a future work, and I bought the book. At the time, I did not envisage that I would eventually use six of Planck’s drawings in a solo exhibition in Scotland.

-(detail)-(i),-inkjet-print,-2017.jpg)

Roger Palmer. Refugio (Isla Robinson Crusoe) (detail) (i), 2017. Inkjet print.

Once I became aware of the connection between Alexander Selkirk and Robinson Crusoe, I travelled from Glasgow to Selkirk’s birthplace in Fife. In 2017, a project began to take shape in association with Fife Contemporary. The idea of making an exhibition close to Selkirk’s home of Lower Largo seemed interesting, as did the possibility of exploring the slippage between Selkirk and Crusoe through combinations of historical and contemporary modes of representation. The realisation that 2019 would be the tercentenary of the first publication of Robinson Crusoeadded extra energy to the project and increased my determination to visit the remote Chilean island where Selkirk had been marooned and which, in 1966, was renamed Isla Robinson Crusoe.

JMcK: What does Selkirk tell us about his times and what can we, in the 21st century, learn from his remarkable story in terms of political migration or solitude?

RP: Selkirk was a professional sailor employed in what was, to all intents and purposes, colonial piracy. His decision to leave an unseaworthy ship in the hope that he would soon be picked up by another vessel was overly optimistic. We know that he gradually acquired the necessary resources for lone survival and that, following his eventual rescue, he found it difficult to return to his former life in Lower Largo (near Kirkcaldy). Perhaps after four-plus years spent in isolation, his uncomfortable and disorienting return “home” made him an unwitting victim of the colonial policies that had led him to a life at sea.

-(detail-(ii),-inkjet-print,-2017.jpg)

Roger Palmer. Refugio (Isla Robinson Crusoe) (detail) (ii), 2017. Inkjet print.

JMcK: Can you describe the work, which ranges from silver gelatin photographs to wall drawings?

RP: Several of my projects combine silver gelatin and colour photographs with temporary wall-based works in different media. For Refugio – After Selkirk After Crusoe, I used two exhibition rooms in different ways. In one, a group of silver gelatine photographs of uniform size were displayed adjacent to graphite wall drawings, the surfaces of which highlighted accumulations of blemishes and gallery repairs. In each of the photographs, the gaze moves from material evidence of the Fife shoreline towards a maritime horizon. The wall drawings feature a young white man, enlarged to life-size from Planck’s illustrations, grappling with his solitary status. I wanted to encourage a conversation between two different forms of representation; the grainy surfaces of monochrome photographs made near Lower Largo and the grainy, uneven and varied textures of the graphite drawings with their references to isolation.

Roger Palmer. Bones, in Refugio - after Selkirk after Crusoe, Kirkcaldy Galleries, 2019. Vinyl, marker pen, map and inket photograph, 301 x 410 cm. Photo: John C McKenzie.

In the next room, two mixed-media works represent illustrations from Robinson using digitally enlarged vinyl modified with marker pen and fluid applications of acrylic paint. Each piece also includes framed artefacts – in Bones, a map of Isla Robinson Crusoe is echoed by a distinctive red shape in an adjacent photograph, Fire. In making this comparison, the eye would pass over the lower section of a temporary wall work, a distinctive shape that vaguely echoes that of the island and which includes evidence of human bones in a shallow pit. From our detached viewpoint, we act as witnesses as the looming figure of Crusoe encounters evidence of cannibalism.

JMcK: When did you first make wall art?

RP: In the early 90s, I started to make text-based wall drawings. I recall seeing wall drawings by artists such as Sol LeWitt and David Tremlett. When my partner returned to South Africa to teach, we bought a tiny house and, since I didn’t have a studio, I ended up making text works on the walls using graphite and acrylic paint. I also worked on gallery walls as part of mixed-media exhibitions; for instance, in a solo show in Salzburg, I drew an enlarged line of Gothic text taken from a fragment of an old German newspaper.

JMcK: Your extensive travels enable a postmodern interrogation of language, politics and colonialism.

RP: Initially, my working journeys were limited to the UK and Ireland. I had met my South African partner in the UK in 1976, but it was difficult for us to travel to her former home until apartheid started to relax. I went for the first time in 1985 and, as a result of this visit, made a photo-text project, Precious Metals (1986). In the late apartheid era, Precious Metals perhaps offered a different perspective on South African politics and the colonial responsibility for apartheid. By looking from a position of focused detachment at two ordinary, so-called “coloured” settlements in the Western Cape, I developed ways to examine combinations of silver gelatin photographs and texts that were different from those that played out regularly through the media.

JMcK: It’s interesting that Glasgow University has just agreed to implement a programme of restorative justice, to raise and spend £20m to atone for having benefited from the slave trade. It is the first institution in the UK to do so.

RP: It was a major factor in this city acquiring its 19th-century status as second city of the Empire. Recent research and a television documentary have placed Scotland’s role in the slave trade more firmly in the public eye. The wealth that was generated was extraordinary and is still evident in the city’s rich architectural heritage and some of its street names.

JMcK: I’m interested in the parallels and contrasting means that you employ – technically refined photography against raw and ephemeral wall drawings – and the fact that the work has grown in response to your travels and experience of different cultures. It is not a dialogue as such, but you seem to use one to bounce off against the other.

RP: I began to work with photography through problems of representation that I was unable to resolve in painting and printmaking. As a result, I have always treated photography as a form of drawing, particularly through my silver gelatin photographs, which are made in rudimentary but precise ways – a 35mm camera with standard lens, always the same film, paper, chemistry, etc. I make my own prints through an exhausting process, striving to achieve a delicate balance between scale, tonality and surface. The relationship between the picture plane and the image that emerges from that surface has always been of great importance.

JMcK: There is a strong element of politics in everything you do? Has that always been the case?

RP: In the early 70s, I became aware that conceptual and feminist artists engaged with problems of representation through photography and were interested in how photographs might be used in conjunction with other media, notably text. When I worked in the UK in the 70s and 80s, I combined photographs and texts to make oblique statements about the political dimensions of British landscapes. Grainy black-and-white photographs were accompanied by short texts, one or sometimes two lines at most. I was interested in the dialogue between the photographic statement and a parallel, complementary textual proposal.

-(detail),-silver-gelatin-photograph,-2015-(i).jpg)

Roger Palmer. Partial Eclipse (Kronstadt) (detail), 2015. Silver gelatin photograph.

JMcK: Can you explain how your Russian project, Partial Eclipse, came about?

RP: Partial Eclipse was begun on a residency in Kronstadt, Russia. It recalls the 1921 Kronstadt Rebellion, in a group of photographs I made on Kotlin Island close to St Petersburg. It also references suprematism and, in particular, Kazimir Malevich’s paintings made between 1915 and 1921. The title Partial Eclipse is drawn from a 1914 Malevich painting, Composition with Mona Lisa, in which oil paint, graphite and collage are combined in overlapping layers that include the hand-painted Cyrillic words for “partial” and “eclipse”. At the time of my visit, a partial eclipse of the sun occurred and I walked along gloomy streets in St Petersburg hoping in vain to see this particular Malevich painting on display at the Russian state museum.

-(detail),-silver-gelatin-photograph,-2015-(ii).jpg)

Roger Palmer. Partial Eclipse (Kronstadt) (detail), 2015. Silver gelatin photograph.

JMcK: You employ the modernist grid as a means of presenting 20 silver gelatin photographs.

RP: The 20 photographs of Partial Eclipse suggest various material layers, including references to political figures or the city’s naval history. Others focus on different styles of painting encountered in the urban realm. The photographsare displayed on a tilted wall drawing: a rectangle of the same overall dimensions as the grid of photographs. Although partially obscured by the images, blemishes in the studio wall are enhanced by red wax rubbed into its surface. In making a red rectangular drawing, I was aware of Malevich’s theories on the non-objective supremacy of colour. I also read about the bloody end to the Kronstadt mutiny brought about by the Red Army.

.jpg)

Roger Palmer. Partial Eclipse (work-in-progress); digital substitutes for framed silver gelatin photographs, wax crayon, overall size 300 x 420 cm approx.

JMcK: Sharing the centenary with Partial Eclipse is Following the Starry Plough, which is installed on your studio wall at the moment.

RP: The Starry Plough was the flag flown by the Irish citizen army during the 1916 Easter Rising. The motif proposed that a free Ireland would control its own destiny “from the plough to the stars”, symbolising the present and the future of the working class. A simplified version of the flag comprising seven white stars on a blue ground was designed for the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union in 1934.

Roger Palmer. Following the Starry Plough, studio work-in-progress, 2019. Silver gelatin photographs, emulsion paint, 272 x 580 cm.

I wanted to find a way in which to focus my photographic practice for a work that would encompass the island of Ireland. By superimposing the 1934 Starry Plough flag on a rotated map of Ireland, I used the positioning of its stars to identify seven random zones for making photographs. In September 2015, 100 years since the first unveiling of the Starry Plough, I made a road trip across Ireland spending about three days in each star-shaped zone. The work is as yet incomplete, but my hope is that I can find a suitable way to combine a series of seven photographs, one from each of the working zones, with an enlarged wall painting of the flag motif.

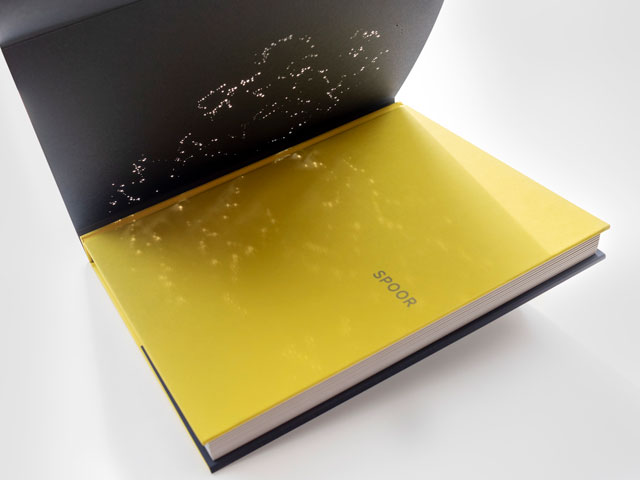

Roger Palmer. SPOOR artist's book, GOST, London, 2019.

JMcK: How did your project Spoor come about?

RP: I made photographs by following rail routes across South Africa. Many of these routes are obsolete and yet their material presence remains, especially in the territory between town and township. Although the train tracks are now disused, many are, in fact, still “in use”. They have become footpaths, so they still offer routes for local travel in rural communities that remain largely fractured and divided.

.jpg)

Roger Palmer. SPOOR, GOST Books, 2019, (Confidence, Mpumalanga, 2016).

As an artist’s book project, I decided to combine sequences of colour photographs with a form of mapping on dark pages that separate each of the picture sequences. Silvery place names are distributed across these pages, which are devoid of other information. A laser-cut dust jacket and a concluding double-page of dots both plot the several hundred stopping places of my various working journeys. As clusters of yellow or silver spots, they might suggest a star map: something that is both familiar and yet completely out of reach.

.jpg)

Roger Palmer. SPOOR, GOST Books, 2019, (Calitzdorp, Western Cape, 2015).

JMcK: I’m interested in how the Robinson Crusoe project connects to your new publication Spoor and photographs of disused railway lines in South Africa?

RP: These projects were developed concurrently. Perhaps they share a common theme of examining colonial legacies through combinations of two or more modes of representation. But their form, and therefore their mode of reception, are markedly different. At some future point, I might come up with a way to exhibit Spoor, but at this time I have no real idea how.