Left: Max Liebermann, Portrait of Prof. Dr. Carl Bernstein, 1892. Oil on cardboard, Private Collection, Switzerland. © SIK-ISEA, Zurich. Photo: Philipp Hitz. Right: Felicie Bernstein as Bride, 1872. © Stiftung Stadtmuseum Berlin.

Liebermann Villa at Wannsee, Berlin

24 May – 8 September 2025

by SABINE SCHERECK

Avant garde art at the turn of the 19th century with its impressionism, fauvism and cubism had Jewish artists such as Camille Pissarro, Béla Czóbel, Marc Chagall, Amedeo Modigliani and Sonia Delaunay at the forefront. Out of public sight, though, were the gallery owners and collectors shaping the art world by helping the artists get seen, finding buyers and thus supporting them. Some of them were also of Jewish origin. In Berlin, the most influential of these was the art dealer Paul Cassirer, who opened his gallery in 1898 and championed French impressionism. However, he was not the first to showcase French impressionist art in Germany’s capital. In 1882, the Jewish art collectors Felicie and Carl Bernstein had brought their newly acquired impressionist paintings from Paris to Berlin and presented them in their grand home – and this at a time when the burgeoning impressionist style was not even an accepted art movement in France. The Bernsteins held regular salons where Berlin’s art scene mingled, among them the German impressionist painter Max Liebermann. The Liebermann Villa in Berlin is now dedicating its exhibition Berlin. Cosmopolitan – The Vanished World of Felicie and Carl Bernstein to them. It illuminates a rarely seen microcosm within the art world and brings a fascinating network to light. The Villa has done valuable pioneering work, bringing the couple to public attention for the first time. Since 2013, Chana Schütz, who has curated the exhibition with Emily Bilski, has been tracing the couple’s history.

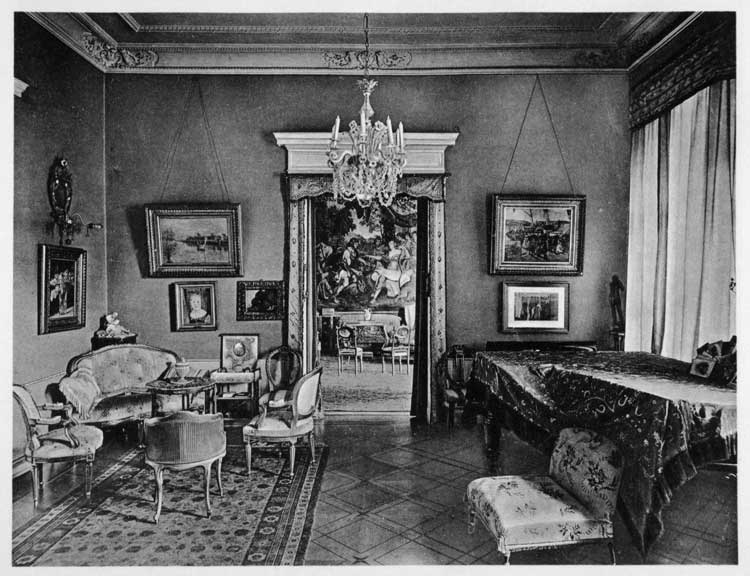

J. Egers, Music Room at Stüler Street 6, Archive Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden.

The story of the Bernsteins begins in Russia. Carl Bernstein was born in 1842 in Odessa, but because his Jewish origins prevented him from studying law in Russia, he travelled to Germany to pursue his education. His qualification then enabled him to practise and even teach law in Russia, yet antisemitic politics in the country made a long-term career in academia impossible. In St Petersburg he met his future wife, Felicie, who, like him, came from a prominent, well-to-do Jewish family. Following the French example of the salon, her father introduced one at his St Petersburg flat, where the 18-year-old Felicie acted as a host. Having been educated in Dresden, she, too, was well-versed in German. In addition, as was common among Russians of their social rank, they had a great affinity with France, which was strengthened by family links to the country. The couple married in 1872 and after extensive travels through Austria and Italy, set up home in Berlin a year later, furnishing it with lamps, tables, chairs, cupboards and trunks acquired on their journeys. They also had Japanese vases, oriental carpets and an Indian table. When they moved to a bigger house, this was enriched by lavish French furniture. Their house, with all its exotic treasures, was a marvel and much admired by visitors for its cosmopolitan flair. The couple’s passion for French culture made them unofficial ambassadors for France, which was particularly relevant after the Franco-Prussian war, which had ended in 1871 and led to the creation of the German empire, known as the Kaiserreich. It was a period of buzzing development and made Berlin a good place to be.

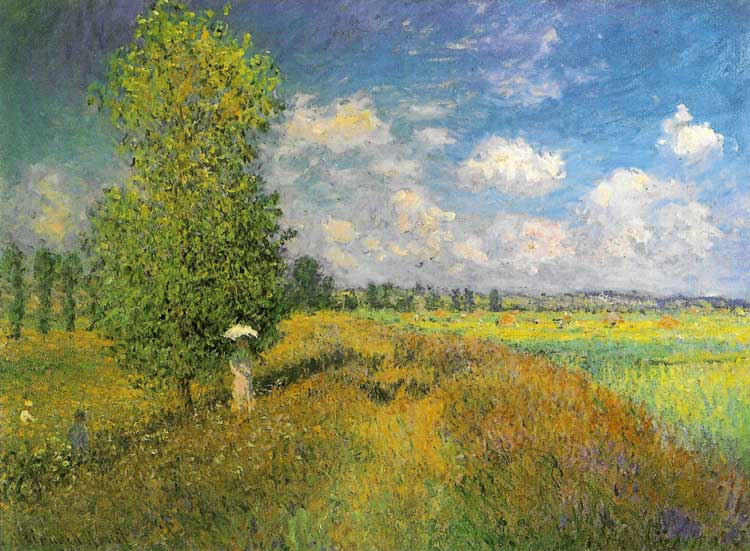

Claude Monet, Summer, Poppy Field, 1875, as reproduction, location unclear.

After a brief introduction, the exhibition presents through portraits some of their illustrious and renowned guests who would easily engage in debates sparked by the art displayed at the Bernstein house. Among them were the artists Sabine and Reinhold Lepsius and the museum directors and curators Alfred Lichtwark, Wilhelm Bode and Hugo von Tschudi, the last of whom is shown here in a drawing by Liebermann. Most intriguing, however, is a painting of the Danish critic and writer Georg Brandes. Having seen his powerful portrait at the Paris exhibition Christian Krohg – The People of the North, he is a familiar figure to me. Krogh painted him in 1879 as a young man but, here, his portrait shows him with grey hair. Liebermann captured him in 1902, almost 20 years after Brandes’ stay in Berlin, where he lived from 1877 to 1883. Brandes was in the city just long enough to witness the impressionist paintings at the Bernsteins, who lived only a few houses away from him. He was also one of the first to report on the new style, when writing an essay on Japanese and impressionist art for a Danish newspaper.

Édouard Manet, Departure of the Folkestone Steamer, 1869. Oil on canvas as reproduction, Philadelphia Museum of Art, The Mr and Mrs Caroll S. Tyson Jr. Collection.

Among the dozen works from Paris that documents cite were in the Bernstein’s collection were Alfred Sisley’s The Seine at Argenteuil (1872), Claude Monet’s The Petit Bras of the Seine at Argenteuil (1872), Summer, Poppy Field (1875) and Édouard Manet’s Departure of the Folkestone Steamer (1869), the last of which was presented to the couple by Carl’s cousin Charles Ephrussi, who had already started collecting French impressionism. The Bernsteins even visited Manet’s studio, where they bought three still lives on the spot: White Lilacs in a Glass Vase (c1882), Bouquet of Peonies (1882) and Roses, Tulips and Lilacs in a Glass Vase (1881). It is fascinating to learn that Pissarro’s gouache Peasant Women Working in the Fields, Pontoise (1881) was also part of their collection bearing in mind that a few kilometres away from the Liebermann Villa in the southwest of Berlin, the Museum Barberini in Potsdam is showing a big retrospective, The Honest Eye: Camille Pissarro’s Impressionism. The Bernstein’s purchases also prove that women were prominent in the French art scene at the time as they acquired works by Mary Cassatt, Berthe Morisot, Eva Gonzalès and Marie Cazin, mainly showing women and children.

Édouard Manet, Bouquet of Peonies, 1882. Oil on canvas, reproduction, location unclear.

While Bernstein’s acquisitions were first shown exclusively to their circle of guests, they were presented to a wider audience when the couple lent them, in October 1883, to the gallerist Fritz Gurlitt. He showcased them with works belonging to the Parisian art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel, who hoped to gain a German market for this new artistic style. The Berlin art world did not take to impressionism right away, yet the seeds for establishing it in Germany were firmly planted.

Of all the above-named works introducing French impressionism to a German audience, only Sisley’s The Seine at Argenteuil is on display here. That may seem disappointing but, in fact, it is an achievement as some of the works are now in far-flung places such as Japan and the United States, while others are lost without a trace. A map in the last room shows what has become of the works. The couple had no children. Carl died in 1894, and Felicie moved into a smaller place with a female relative. She continued to collect art and when she died in 1908, she left the works to her friends to support them: these included museums, but also Liebermann, who had always been impressed by the Bernsteins’ art collection. He said: “The [Bernstein] collection contained Manet’s most beautiful still lifes […] but above all wonderful Cl[aude] Monets, including the famous Champs de coquelicots, which Mrs Bernstein left me because I had always particularly admired this painting.” Their unwavering support of French impressionism also had a profound influence on Liebermann’s own art collecting. But even before he had made friends with the couple in about 1884 or 1885, he had formed his own links to French impressionism. As a young artist, he had travelled to Paris in 1873 to further his studies. The following year, he spent the summer in Barbizon and engaged in plein-air painting, which set him on the path to becoming an impressionist painter himself.

It is fortunate that photographs of the lavish and luxurious Bernstein home have survived. For this exhibition, they have been enlarged to skilfully cover the walls. This not only enables visitors to picture themselves as guests at the Bernsteins but also to spot the paintings discussed on their walls.

The exhibition is small, yet opens a chapter in Berlin’s cultural history that had long vanished from sight. It also follows the current shift of venues to look behind the scenes by featuring art collectors and their crucial contribution to the art world as did the Brücke-Museum last year when presenting the art collector Hanna Bekker vom Rath and as will the Musée de l’Orangerie this October when honouring the gallerist Berthe Weill who promoted young avant garde artists such as Modigliani in Paris at the turn of the 19th century.