It Takes a Village, installation view, Ditchling Museum of Art + Craft, East Sussex, 5 July 2025 – 1 February 2026.

Ditchling Museum of Art + Craft, East Sussex

5 July 2025 – 1 February 2026

by ANNA McNAY

To mark its 40th birthday, Ditchling Museum of Art + Craft is hosting an exhibition all about reaching out: reaching out and exploring the breadth of the collection, its many (inter-)connections and peripheral figures and bringing them and lesser seen objects to the fore; reaching out and connecting to present-day villagers and erstwhile members of the former Guild of St Joseph and St Dominic;1 reaching out to those with access or other needs, including neurodivergent visitors, to make the exhibition and museum an easier place for them to come to; and, last but absolutely not least, reaching out to survivors of abuse, through a project carried out together with the Methodist Survivors’ Advisory Group, to learn how to sensitively show works by Eric Gill, one of the key artists in village history, but who is known for his abuse of two of his young daughters, Elizabeth (Betty) and Petra.

As an example of this outreach, the museum worked with year 11 students from a local secondary school to make letterpress posters on its presses, inspired by the posters in the collection, and both sets now hang in the Hilary Bourne Gallery, alongside the original press. The exhibition really opens, however, with a specially created pictorial map, showing the locations of different artists’ homes and studios around the village. It is really helpful for building a visual impression of the place and space over the past century (although I did also comment to the museum’s director, Steph Fuller, that we need a family tree, as well, as there is so much interrelating and intermarriage).

The main body of the exhibition contains items selected by more than 50 contributors, working with the curator Gregory Parsons, a craft specialist, and it presents rarely seen discoveries alongside well-known pieces by craftspeople, including Gill, David Jones, Joseph Cribb (Gill’s first assistant and his successor at Ditchling when Gill moved to Capel-y-ffin in Wales) and the weaver Ethel Mairet. Fuller says: “The objects are really important, but how they got there as a product of that person and their skills and their life and their experiences seems to me to be what’s really interesting – that whole package of things. The Guild was a really extraordinary, radical social experiment. It worked in some respects and not so much in others, but there were a lot of people who were committed to it over a long period, and I think it’s really admirable what they were trying to do. A lot of it is very resonant for now, too, because it’s about living in harmony with nature and low consumption and having one good quality thing that does the job. And so I thought it would be good to foreground some of that a bit more rather than just focusing on one man [Gill], who was only there for part of the time [1907-24, with the Guild only being founded in 1920], who has this very dramatic private life and tends to dominate the conversation.”

Mary Ginnett by Louis Ginnett, no date, Mary Ginnett in black and cream cloak Collection of Ditchling Museum of Art + Craft.

First among a number of items of clothing on display is an art deco striped cape, modelled by Mary Ginnett in a portrait by her father, the Ditchling artist Louis Ginnett (Portrait of Mary, 1920), which hangs opposite. “When you see it, it's basically a cream-and-black striped cloak,” says Zenzie Tinker, a conservator who worked on the object, in one of 12 oral history interviews with people connected to the museum (played in the gallery, but also available via the website). “The black is velvet and the cream, it’s a very complicated weave … Artists often accumulated garments that they would dress their sitters in and I’m sure he chose this because it’s quite a dynamic garment with the stripes and the folds and the lustre of the velvet and the difference in the texture between the cream areas and the velvet areas. So, it would have been really challenging to paint and would have shown his painting skills off very well.” The cape itself shows off the unknown maker’s skills as well.

Amy Sawyer, Landscape Appliqued Jacket. Collection of Ditchling Museum of Art + Craft. Photo: Tessa Hallmann.

Next to this is a very different jacket by Amy Sawyer, an artist who lived in Ditchling for most of her life, until her death in 1945, and quite an eccentric woman by all accounts. She started out as a painter but developed what people describe as a “withered hand”, probably poisoned by the lead in the paint. She took up writing plays and making textiles. When this jacket was being conserved, they found that there’s more ease built into one side of it, which the experts think means Sawyer might have modified the pattern to allow for more movement for her damaged arm. Either way, it depicts the beautiful rolling hills around the village and has big, bold stitchwork.

One of my favourite works on display is the beautiful and tender Madonna and Child – Our Lady of the Hills (c1921) – painted by Jones, shortly after he almost died of trench fever, in which the baby really has the form of a curled-up, sleepy infant being gently kissed on the forehead by its mother. Next to this is the door of a safe that was used to store silver items at the Guild, also painted by Jones with the Agnus Dei (c1925). Quite a contrast.

David Jones, Our Lady of the Hills, 1924. Collection of Ditchling Museum of Art + Craft.

Another favourite exhibit is the set of wood-carving tools belonging to Cribb and comprising chisels of every imaginable size in a velvet roll and battered and dented mallets. It is hard to conceive of these blunt instruments being used to create such exquisite works as the stone relief carving of a girl’s head, undated, looking coyly down across her shoulder, on display nearby.

In among a vitrine of wood blocks, is a block and print by Alan Taylor, Cribb’s son-in-law, which shows Cribb and Taylor and Peter Cribb, his son, fishing for pike at their favourite pond. Some of the items are so everyday they can’t fail to make you smile.

Hanging on the wall are the Rules of the Guild of St Joseph and St Dominic (mid- to late-1920s), written and decorated by Cribb and originally hung in the Guild chapel. Anton Pruden, grandson of the silversmith Dunstan Pruden, who is also a silversmith and goldsmith and has a jeweller in the village, chose this as one of his objects, noting: “The central tenet to this is that work should be … the centre of their life … not the means of buying leisure.”

It Takes a Village, installation view, Ditchling Museum of Art + Craft, East Sussex, 5 July 2025 – 1 February 2026.

A wall of portraits of key characters in the village, where the interrelationships get really interesting – not to mention complicated – begins with a pencil portrait of Mary Gill (Eric’s wife) by Jones (1923), which hangs above a photograph of Jones, who was engaged but never married to Gill’s daughter Petra, by Janet Stone (1966). Toward the bottom of the salon-style hang are a self-portrait and a portrait of the committed distributist Philip Hagreen (both no date) by Edgar Holloway, a draughtsman who later turned his skills to lettering for signs, and a playful caricature by Hagreen of George Maxwell (c1950), who built looms, homes and the Guild’s carpenter’s shop.

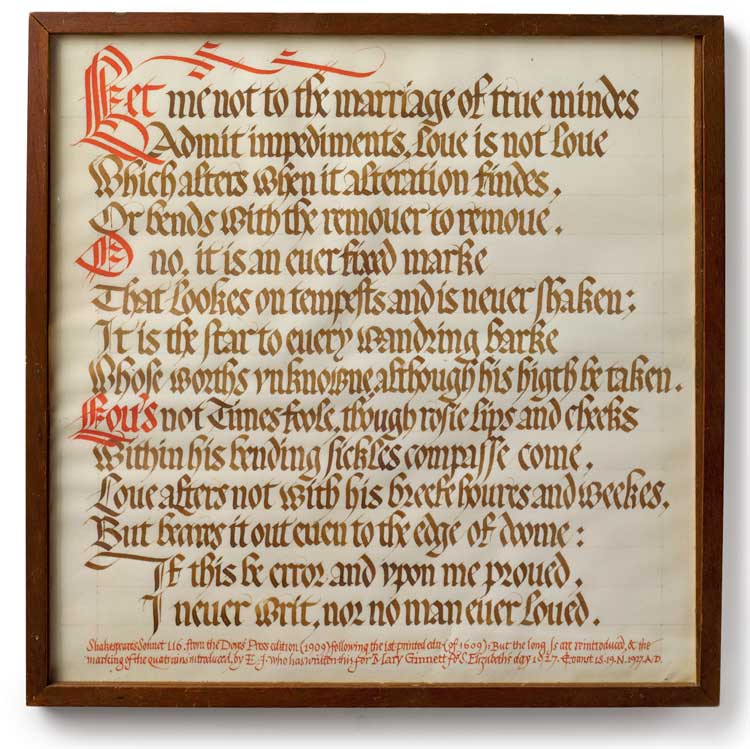

Edward Johnston, Shakespeare's Sonnet CXVI 1927 (used as book cover). Collection of Ditchling Museum of Art + Craft. Photo: Sara Morris.

Another tender item is Shakespeare’s sonnet CXVI, written in beautiful calligraphy by the typographer Edward Johnston – whose name is synonymous with the London Underground – for Mary Ginnett (1927). Ewan Clayton, a calligrapher and writer and member of the Guild before it closed in 1988, says: “It’s probably the best piece of calligraphy that they have in the museum. It’s a square-framed vellum panel and it’s from late in his life. It’s a medieval script, but it’s very him.” Johnston, despite being an old friend of Gill and having followed him to the village, was one of the few males in his circle not to join the Guild. Nearby, his pens and penknife are also on display.

On opposite walls, two series of prints bring a touch of humour to the exhibition. Wood engravings by Hagreen (c1937-47), who shared a studio in Ditchling with Jones, show his skill in conveying complex religious, social and political views through the simple use of line. An example is a colour image of a snake wrapped around an apple tree, with the label “Eat more fruit” and the caption “The first advertiser”. On the facing wall, there is a selection of small rhyme sheets, produced and printed by St Dominic’s Press (no date), with very funny poems by its founder, Hilary Pepler, and illustrations by Mary Dudley Short. This humour is truly needed as the content and tale about to be told in the Gill section weighs heavy.

In a statement on its website, the museum acknowledges that Gill is: “An artist central to our narrative and whose importance to art and design history in the UK and around the world is impossible to ignore, but whose diaries record that he sexually abused his daughters as well as participating in other disturbing sexual acts.” In 2017, Nathaniel Hepburn, the director at the time, said: “My view as a curator was: he’s an artist, and we show his work. I hadn’t felt it [his biography] would be an issue for us, until one day I found myself looking at work we would feel uncomfortable showing.” Here, he is referring to an envelope in the Ditchling archives, on the back of which, in two columns, Gill had listed, in some detail, the measurements of various parts of his daughters’ bodies, his own measurements and, at the bottom, his penis size, erect and flaccid. This was included in the exhibition Hepburn put together, which sought to ask the question: “Is it possible to enjoy Gill’s art when we know about his abuse?” The envelope is not included in today’s.2 While that exhibition largely received a positive response, there were also comments such as “Angry at the focus on Gill’s behaviour with no acknowledgement of its impact on the lives of his daughters.”3 What Fuller primarily wanted to do differently was to let the survivors speak: both those in the methodist group, and also Betty and Petra themselves. (Both sisters are now dead, but the project spoke with one of Petra’s granddaughters and somebody who knew Petra.)

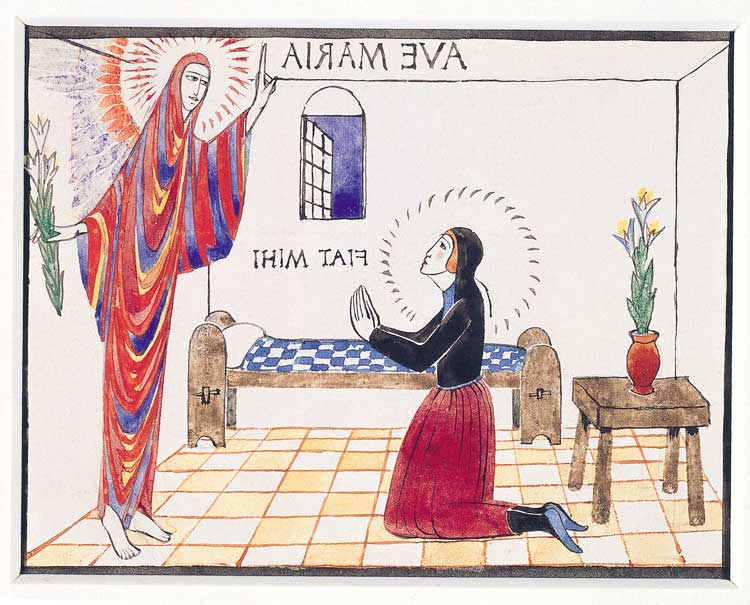

Eric Gill, Annunciation, c1912. Collection of Methodist Modern Art Collection.

A fascinating corner explores religious motifs and the portrayal of power relations, looking in particular at the Annunciation. Annunciation (c1912) by Gill is on loan from the Methodist Modern Art Collection and is shown both as it is, an original reverse drawing for a mirrorscope slide, and with a vertically flipped and projected image, as was the intended product of the object. It is shown alongside The Annunciation (1922) by Jones and Annunciation (no date) by Hagreen. Survivors from the Methodist Survivors’ Advisory Group commented on the different dynamics, suggesting that the Gill angel, looming over a terrified Mary in her bedroom, feels oppressive and controlling, whereas Jones’s scene is set outside, thus feeling freer. In starker contrast, Hagreen’s annunciation shows the angel kneeling before Mary, with an attendant reversal of power dynamics altogether.

.jpg)

Philip Hagreen, Annunciation, no date. Collection of Ditchling Museum of Art + Craft.

Alongside three images of embracing couples by Gill (two drawn, one sculpted) and a drawing of each daughter in profile, display cases and vitrines show drawings, stories and photographs by and of Gill’s daughters, placing them centre stage, as more than just anonymous names or “victims”. In addition, Petra’s self-made Assam-silk wedding dress hangs proudly on a mannequin, a symbol of hope for a better future. (Petra was taught to weave by Mairet, and there are many stories about her being scolded for muddling up her counting and getting things wrong.) Of the Gill images, an anonymous survivor says: “We have chosen these images to show how Gill twisted the tradition of Divine Love into something perverted.” Can the images be divorced from the story of their maker? They truly are breathtakingly beautiful objects, but how can we feel that when we know the context in which they were created? Another survivor notes: “Some people have even been heard to say: ‘We need to separate the artist from the deed, and see what an amazing artist Gill was.’ Total rubbish, his abuse is so often portrayed in his art, and what he did to his sister and daughters, he even wrote about in his diaries, as if it was part of the normal day-to-day routines. This man was a paedophile no matter whether he was a good painter or not, he was a paedophile first, middling and last, and that is how he should be remembered.” Case closed? The same survivor, Vivien, continues: “The reason we have collaborated on this project was because we wanted to stop hiding those people, like myself, who have been abused, and told to keep quiet, yet the perpetrator, even when they are convicted, are still the ones that make the headlines and it’s their voice that is heard.”

A hasty summary of take away points from such a challenging project seems too flippant, but Fuller says it was made clear by the survivors from the outset that the solution is not to hide the work away, as this is what all too often happens with the abuse itself. “No one wants to talk about it because it’s difficult,” she says, “but actually, for them, it’s crucial that it’s possible to talk about it.” Showing the work, along with the correct contextual information, and with appropriately trained invigilators, can perhaps enable this. Fuller certainly feels happier going forwards now the elephant in the room has been properly addressed.

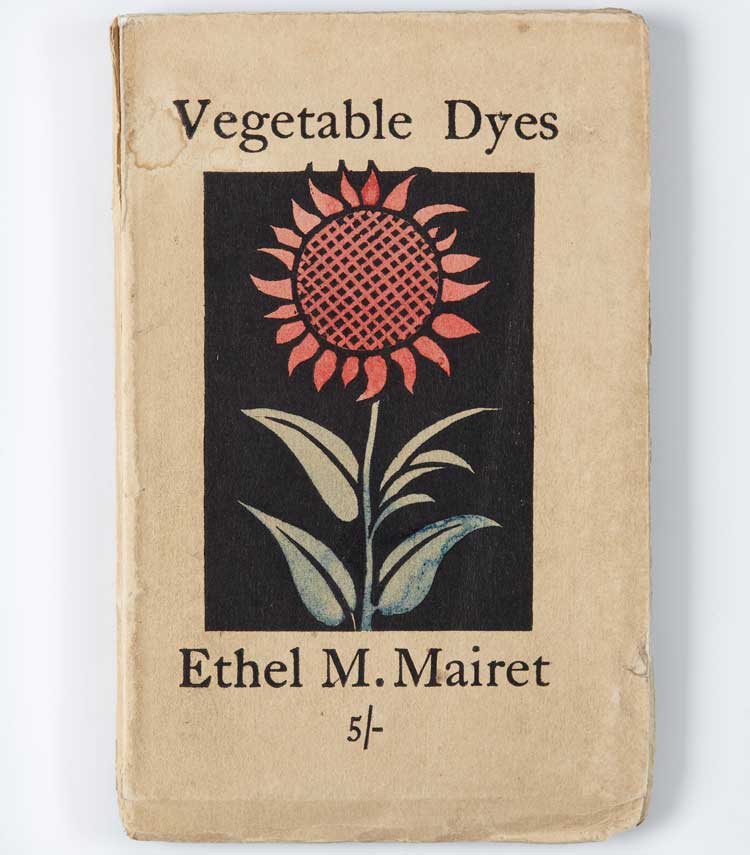

Vegetable Dyes book cover. Fourth Edition 1924. Collection of Ditchling Museum of Art + Craft. Photo: Tessa Hallmann.

The final section of the exhibition is about interaction and access. With a focus on weaving, the disabled and neurodivergent co-curators bring Mairet’s workshop, Gospels, to life, and visitors are given the opportunity to smell some of the plants – woad (blue), gorse (yellow) and madder (red) – used for natural dyes (still grown in – and used from – the museum garden) and to feel some of the different material textures. Alongside, there is an audio track playing the sound of the loom and an accompanying audio description of the workshop. Finally, there is an opportunity to try some weaving for yourself. Fuller is very keen to embed this extended sensory offering and all-important accessibility in the future. “We’re on the journey now,” she says. As an autistic visitor, I particularly enjoyed the scents, but, visiting with my art critic hat on, I would say I was most drawn to and impressed by the section on Gill. Is it worrying that, even in an attempt to banish him from the limelight, he still comes up trumps? Only time will tell.

Whether you are interested in Gill or not, this is still an exhibition well worth visiting, as it brings out objects from the collection that are rarely seen, but which, as indeed was the intention, really add to the story and show that it truly does take a village. The exhibition is set to shape a major collection redisplay planned for 2028. Bring it on!

References

1. An experimental Roman Catholic community of artists and craftspeople based on a medieval model, founded by Eric Gill and others in Ditchling as a community which united work, faith and domestic life, centred on its workshops and chapel. Part of the Guild’s ethos was a Catholic socialist philosophy known as distributism, which was about people being able to be self-sufficient and having enough land to live off.

2. I recommend reading Eric Gill: can we separate the artist from the abuser? by Rachel Cooke in the Observer, 9 April 2017, for a detailed discussion.

3. Eric Gill/The Body by Julia Farrington, in Index on Censorship: A Voice for the Persecuted, 15 May 2019.