Installation view, Art & The Book at The Warburg Institute, London, 22 May – 2 August 2025. Courtesy The Warburg Institute.

Warburg Institute, London*

22 May – 2 August 2025

Senate House Library, University of London**

18 June – 15 November 2025

by BRONAĊ FERRAN

Two exhibitions in central London this summer celebrate the contemporary and historical impact of print and small press publishing.1 At Senate House Library and the Warburg Institute, a spectrum of materials, from socialist pamphlets to activist flyers, from artists’ books to unclassifiable ephemera, has been assembled from special collections for public appreciation. These reveal the deep history of paper and print as a context through and within which practices of autonomous production have long found realisation. The exhibitions also celebrate the role of the library as a gathering point for, a place of access to, and the preservation of sometimes fragile documents that might otherwise be lost to collective memory.

My visit begins at the Warburg Institute, an organisation created around a special collection of more than 60,000 books, thousands of photographs and slides, index cards, library fittings and other items assembled by Aby Warburg in Hamburg, and sent posthumously by his family to England from Germany in 1933-34, to avoid its potential seizure by ascendant Nazi forces. After two temporary locations, the collection found a final resting place at the University of London, where it is the primary inspiration behind the current exhibition as well as a linked season of events under the theme of Art & the Book.

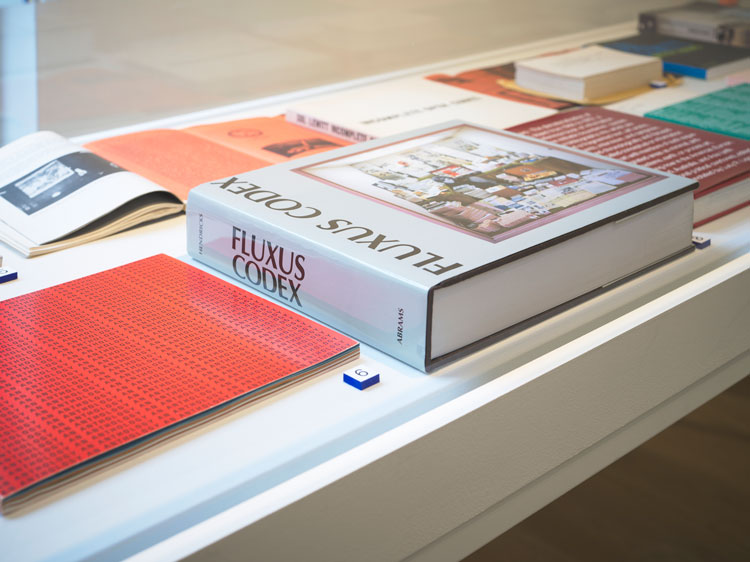

Installation view, Art & The Book at The Warburg Institute, London, 22 May – 2 August 2025. Courtesy The Warburg Institute.

All strands take place within the Warburg’s recently opened, impressively designed extension, comprising an exhibition area and a state-of-the-art auditorium, reached via a welcoming ground-floor reception desk, with an atmosphere of convivial and physical accessibility prevailing within the building generally. The focus of the exhibition and several of the talks is artists’ books, a domain of small-scale (often self-) publishing that grew to be a vogue in the 1970s. The Warburg curator, Matthew Harle, invited two guest curators, Arnaud Desjardin of the Everyday Press and Hlib Velyhorskyi of Biblioteka, to work with him on this project.

The exhibition is mostly centred around a set of homogenously sized vitrines. It forms the centrepiece of a programme that includes short-term residencies by independent bookshops, a series of talks (details of which will be on the Warburg website as they are finalised) and an Art Bookfair that was held over the midsummer weekend. All are open to the public and many of the events (none of which have been recorded or live-streamed) have been well-attended, speaking as this topic does to a range of ages, with artists’ books now a rather fashionable activity, alongside the growth of interest among millennials and gen Z in zine-making.

Installation view, Art & The Book at The Warburg Institute, London, 22 May – 2 August 2025. Courtesy The Warburg Institute.

Infusing aspects of the exhibition are the ideas of Clive Phillpot, an influential art librarian working in London in the late 60s and then from 1977-94 as director of the Museum of Modern Art library in New York. He tends to be cited in any discussion about the artist’s book. For Phillpot, it is effectively its own genre. He became known as one of the first to build up a collection in this area, so situating the concept of the specialist library as one that is interlaced with a cultural history of the artist’s book.

Nonetheless, as a concept, the term artists’ books has somewhat of a contested history, especially in relation to its connection or otherwise with what might have been published by artists before its 1970s’ heyday. This was noted in a 2015 publication by the writer Michael Hampton, who suggested introducing the term “Unshelfmarked” to apply to related material. While pointing towards multiple examples of earlier publications that he views as relevant, he referred to “a volcanic eruption” that occurred in the field after the early 70s, “spreading its plume everywhere” producing “a cloud of formats and multimodal methods, (showcased in both the unique artisanal book and limited edition)” and using diverse techniques of production including “letterpress, pop-up, lasercut, risograph, perfect bound, accordion pleat, giclée, risograph, flip, photocopy, stencil, linocut, comb binding, coil binding, monoprint, leporello, Coptic binding, Japanese stitching” and so on.2

In the 1975 catalogue of a British Council exhibition entitled Artists’ Bookworks, David Mayor, the co-publisher of the iconic magazine Schmuck, offered a rather brilliant critique of a trend towards hermeticism that he saw prevailing in this field. Mayor expressed the hope that the next decade would see a widening out beyond self-referentiality in autonomous production to engage more directly with the sociopolitical realities of the context in which artists’ books were being made.3

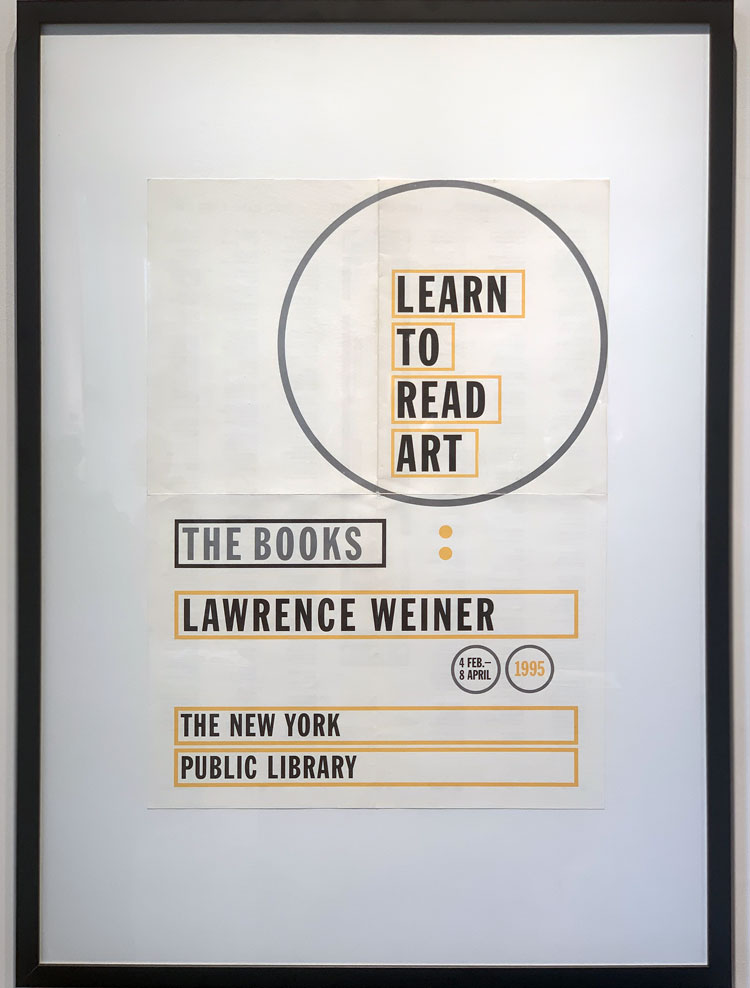

Poster for Lawrence Weiner's exhibition Learn to Read Art: The Books at the New York Public Library, New York, 4 February – 8 April 1995. Installation view, Art & The Book at The Warburg Institute, London, 22 May – 2 August 2025. Photo: Bronac Ferran.

Desjardin, in the vitrines on which he has taken a lead, has focused on presenting a historical perspective through showing numerous books about artists’ books from the late 1960s onwards, drawn from his own collection, that may be read as an attempt to establish a missing canon. Velyhorskyi, by contrast, arrived in London in 2020 with a collection of books about art and architecture as well as photography that he, with associates, had been gathering since 2014 in Ukraine. They were offered a space to place this in Peckham, south-east London, where he started a library that welcomed people and donations, orienting this further in the direction of artists’ books, starting a book fair and then moving the project, in 2023, to a room in Bedford Square in Bloomsbury, central London, owned by the Architectural Association where he had become a student.

A sense in which this intercultural transference – with a library and collection at its heart, itinerant and ending up homed in Bloomsbury – is at some level analogous with the foundational Warburg narrative is reinforced by Velyhorskyi’s emphasis on designing the bookshelves himself. In interview, he has said that the collection now houses more than 8,000 items, thanks to donations from various quarters and places emphasis on how – as in the Warburg library – all the books are openly available on the shelves.

We see homage paid to the ethos of openness and chance connections found in neighbourhoods of proximity in libraries also in this exhibition with a beautifully designed, multifunctional table, covered with catalogues of avant garde publications, some playful artists’ publications and a few more oblique philosophical tomes. On the exhibition’s opening night, this table became the most participatory and rounded part of an exhibition that otherwise appears to have a rather abstracted approach to curatorial interpretation and visual communication. The laying out flat of books, catalogues, anthologies and other items from personal or special collections seems like a missed opportunity to reveal the dynamic interiority of what is on display. Only a few pieces are hung or stand upright. Yet for many of its earlier pioneers, the physicality and materiality of what they were making – the chance for readers to hold and open up the book – was its crucial defining and distinguishing dimension. This was a story shared by Hansjörg Mayer in an interview in Studio International in 2019.

A series of short residencies by bookshops from around the UK (the accompanying literature tells us) falls short somewhat of this objective, being primarily focused (seven out of nine) on more local London-based projects. I sense, too, something of a disjuncture in terms of what is written on the walls and the nature of the material included within the nearby vitrines, as if created by different hands in different phases of planning. I invited Desjardin and Velyhorskyi to comment on how they approached their task as co-curators. Desjardin responded: “The vitrines were split roughly into mainly the more historical material from my collection, providing a bit of context and a trajectory on one side and on the other the more contemporary end of things.” He has also noted that one of the primary drivers behind what they choose to do was to draw attention to “the lack of visibility of contemporary artist publishing despite the vast amount of things released today” and to suggest the questions: “Where are the current libraries and book spaces that make that material available? Why [have] art book fairs become the main space and forum for the display of these productions?”4

Installation view, Biblioteka Book Fair at The Warburg Institute, London. Photo: Bronac Ferran.

A related art book fair, Biblioteka, was duly held in the scorching heat of midsummer London. On my brief visit, I saw examples of early vintage titles changing hands at high prices. There is also a welcome sense here of this very niche area having gained a confidence through surviving everything that has happened, new-media-wise, since the postwar decades. It now seems, in its very discreteness and in many ways, singularity of form, to have gained a cultural resilience, that appears evident in everything to be discovered here, from Brazilian concrete poetry to minimalist books from Singapore, and so on. Many of the stalls were presenting a combination of older and newer materials; some were also showing works engaging with contemporary ecological and political crises, demanding an adjustment of the gaze again away from seeing artists’ books as solely conceptual or aesthetic entities.

Installation view, Biblioteka Book Fair at The Warburg Institute, London. Photo: Bronac Ferran.

In Hampton’s book, he cites Anne Moeglin-Delcroix, one of the world’s leading authorities in the domain of livres d’artists, who has commented that “the artists’ book owes more to the pamphlet (opuscule) than the tome (opus)”.5 For those who take a longer historical view on origins and predecessors, as well as those who are concerned with a wider range of self-published print materials, the concurrent exhibition at Senate House Library is a necessity to visit. My sense on arriving at the space in which this is placed (one has to go to the fourth floor, then receive a special day pass to enter the library itself) is that this is visually a more perceptually stimulating experience than the rather static Warburg exhibition.

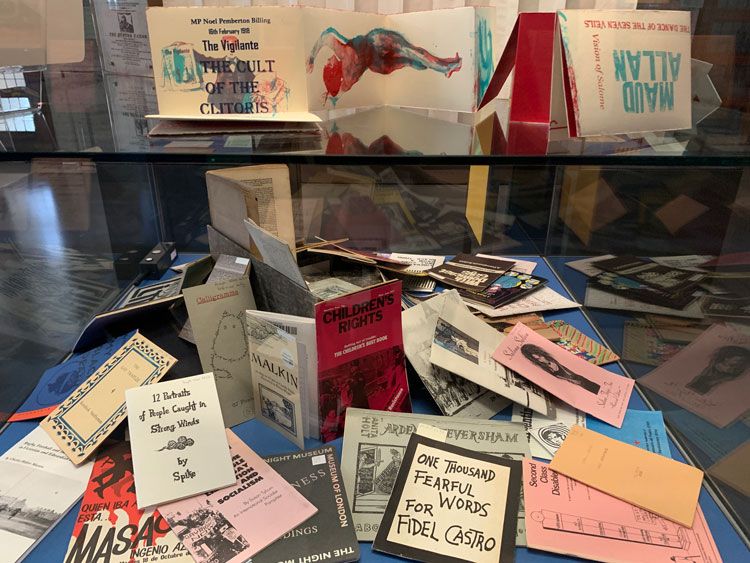

As the exhibition’s subtitle, The Power of Print Unbound, conveys, what is being displayed is a diverse selection of unbound print materials, much of which has a socially engaged, polemical and political edge, although some items are more poetic and reflective in their messages. The placing alongside one another of a stapled copy from 1917 of The Communist Manifesto and a fine example of a German language incunabula from 1491, in the opening vitrine of the exhibition becomes a perfect curatorial entrée for what follows.

Installation view, Spineless Wonders: The Power of Print Unbound at Senate House Library, London. Photo: Bronac Ferran.

Laid out in a series of vitrines of different heights and scales, some wall-based, some freestanding, are numerous examples of print and paper-based materials, arranged in layers and at specific distances from each other, so that a rhythm of multiperspectival movement is achieved. This allows us also to look through and into different phases of social and political history, or histories, being pluralistic and non-divisive in its generative and collaborative effects. On walking through the display area, moving physically between the cases, we grow into the experiences that are being presented, with the exhibition performing an act of opening up for us to view, through a new pluralistic lens, the patterns of emergence in time – and the ideological and political circumstances – that led to various print-based processes being used by people to share their messages with each other, and now with later generations, thanks to careful acts of distilled curation.

The range of what we are seeing has been selected by three co-curators, Tansy Barton and Leila Kassir, academic librarians at Senate House, and Christos Fotelis, who works in paper conservation at the library. They have adopted the phrase “Spineless Wonders” from a broader national/international research project generated initially within Slade School of Art, within which Senate House is a partner. This is a rare sort of exhibition that one feels can be taken in at one glance on arrival yet then justifies spending a considerable time looking closely at its bits. It took two visits for me to fully absorb the various frames of reference that each of the individual items, in a concrete sense, have been chosen to represent or to point towards.

What distinguishes the methods adopted by the three co-curators is that, in several instances, they have chosen not to separate out time periods in a strict way from each other, instead creating temporal overlaps through juxtaposition. This opens up in our heads a sense of historical continuity around, for example, the question of public health, or resistance to fascism, or the demand for equality, as issues that resonate through decades. We sense also a line or continuity between the opening vitrine with its critical inclusion of a very early printed sheet – shortly after the so-called Gutenberg revolution – and later examples of printed and stapled materials associated with self-organising access to education, learning and self-expression that community publishing projects provided for people who, for reasons of class and poverty, might otherwise have been excluded.

What we are seeing is a celebration of the liberating role that small-press publishing has had over centuries in terms of processes of self- and collective representation and, indeed, as a practice of articulated resistance to other forces, acting in this sense as a point of leverage, where the capacity to issue things quickly, and the more cheaply produced the better, might take precedence over design or aesthetics. But as this exhibition vividly shows us, what might pass for cheapness and austerity can gain added value over time. Not least in having survived beyond initial phases of distribution, they enter a different stage and context of reception later. That not everything printed was designed to last for ever – being unbound and unshelfmarkable by intention – adds to the sense of appreciation we now have in getting access to such materials within publicly facing special collections.

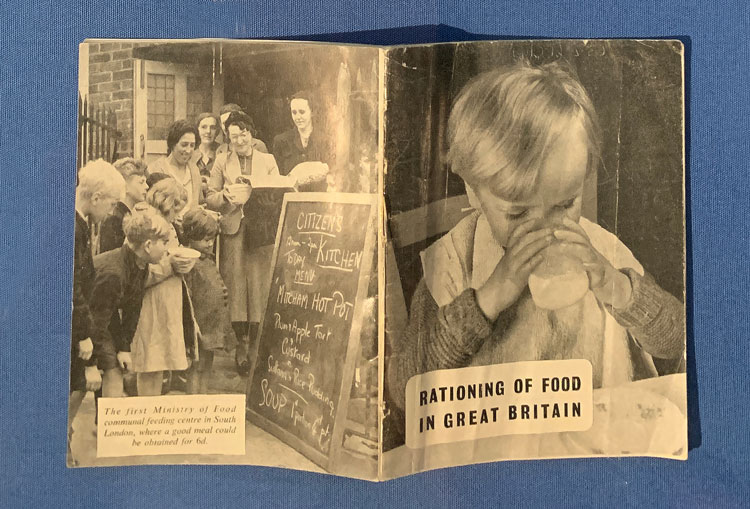

Rationing of food in Great Britain, installation view, Spineless Wonders: The Power of Print Unbound at Senate House Library, London. Photo: Bronac Ferran.

The proto-modernist austerity of type and quality of paper that is conveyed within small publications issued in the wartime period is always a personal favourite. Among those shown here are examples of public health documents circulated by the British government in the early 1940s, that still carry the aura of rationing, of food as well as paper. A pamphlet of a lecture from 1938 headed Health Without Dairy Produce gains added resonance looking back at it now.

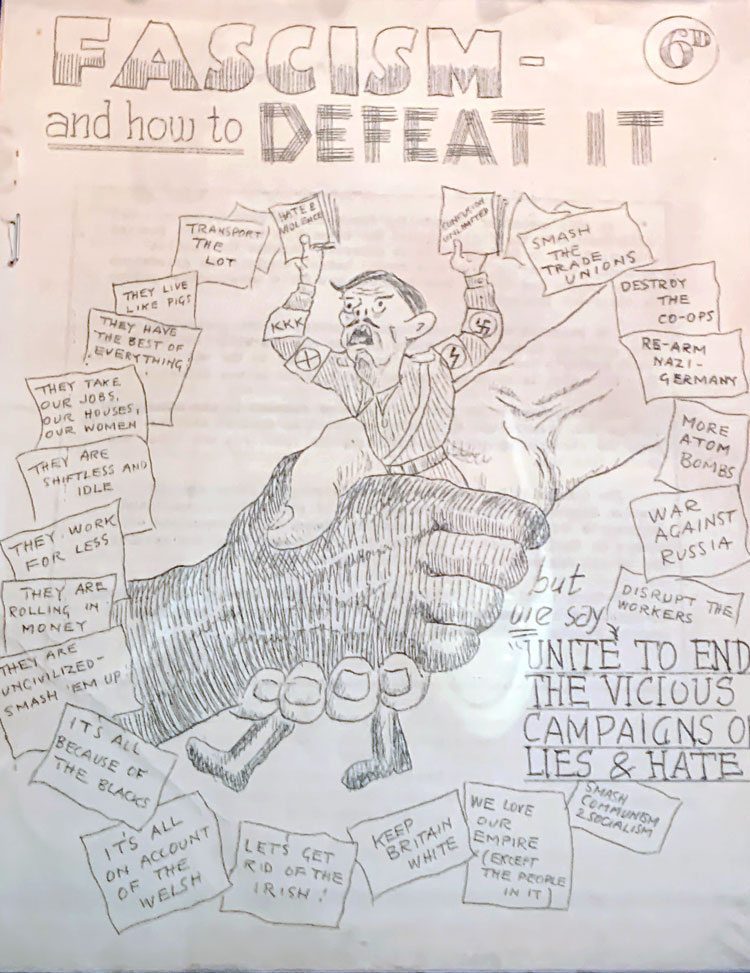

Fascism and how to defeat it, pamphlet, installation view, Spineless Wonders: The Power of Print Unbound at Senate House Library, London. Photo: Bronac Ferran.

Yet other items speak loudly with a renewed sense of urgency, hitting hard on the retina even when we gaze through the protective, low-lit, glass. A critical example of this is a mimeographed publication from the late 1950s that features a white fist and a black fist clutching each other and holding in between them a terrified looking miniaturised figure of Oswald Mosley, then attempting to stand for parliament. The pamphlet is headed FASCISM and how to DEFEAT IT and uses graphic design to communicate a still crucially resonant message, with Mosley shown losing control of the sheets while attempting to use paper and print to get across phrases such as “More atom bombs” and “They take our jobs, our houses, our women”.

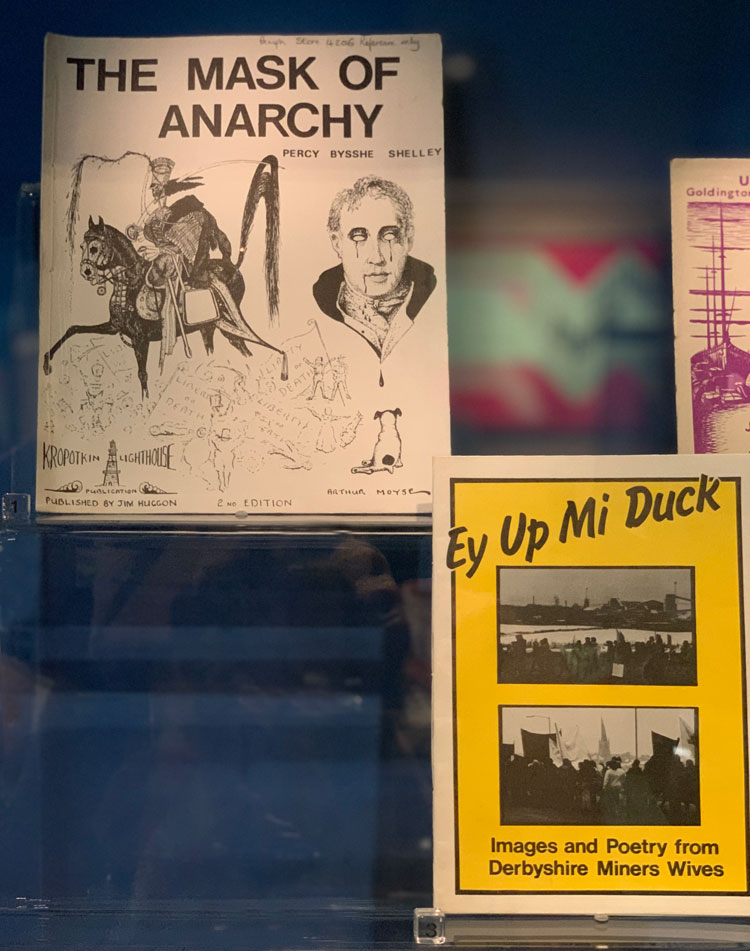

Top left: The Mask of Anarchy, Percy Bysshe Shelley, installation view, Spineless Wonders: The Power of Print Unbound at Senate House Library, London. Photo: Bronac Ferran.

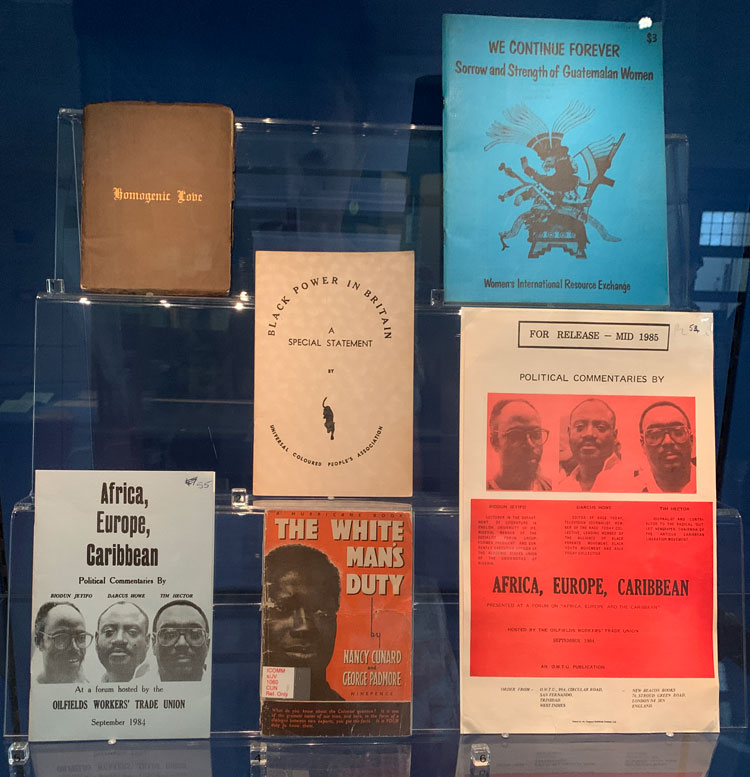

This has been placed in a carefully designed cabinet close to examples of street protest flyers produced in Paris in 1968, a stapled pamphlet entitled Black Power in Britain: A Special Statement (Universal Coloured People’s Association, 1967), stitched pamphlets entitled The White Man’s Duty (Nancy Cunard and George Padmore, 1942), Homogenic Love (Edward Carpenter, Manchester Labour Press Society, 1894), and anti-capitalist and feminist material relating to the City and East End of London in the 1970s and 80s. We see here also a typographically enticing document relating to a Women’s Suffrage Pilgrimage earlier in the century calling for participation and declaiming itself “law-abiding” and “non-party”.

Installation view, Spineless Wonders: The Power of Print Unbound at Senate House Library, London. Photo: Bronac Ferran.

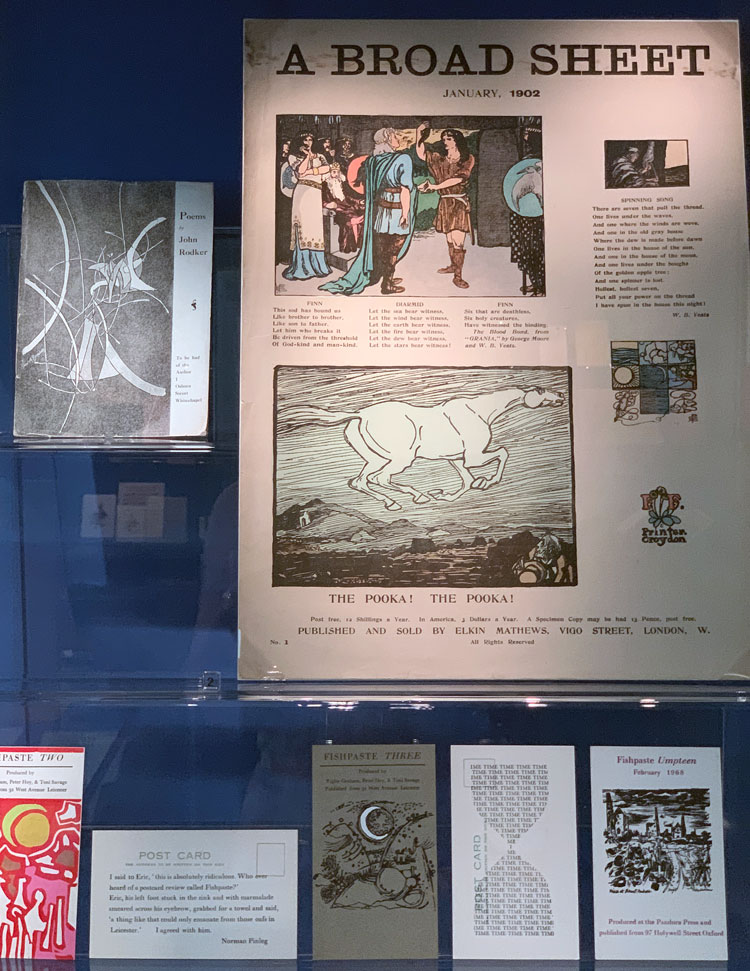

In other cabinets containing a range of fascinating artistic, poetic and theatrical ephemera, the interconnecting of time periods and significant figures and the production of publications comes into dramatic relief, with material featured spanning a range from Percy Bysshe Shelley’s The Mask of Anarchy, to “anti-nuclear songs from printer John Foreman” as well as “queer ephemera, like a photocopied flyer for drag queen Divine”. The extraordinary A Broad Sheet (dated January 1902, Elkin Matthews) has a poem by WB Yeats accompanying what we learn were laboriously hand-coloured illustrations by Pamela Colman Smith and Jack B Yeats, below which we can see the phrase “Printed Croydon”. This specific reference to the means and place of production reminds us that not only is this a beautiful example of text and image conjunction but that it was produced in London at a time when influencing a British intellectual public through the construction of an independent Irish cultural identity by a collective mythologising of a Gaelic history was part of the Yeatsian vision.

A Broad Sheet (dated January 1902, Elkin Matthews), installation view, Spineless Wonders: The Power of Print Unbound at Senate House Library, London. Photo: Bronac Ferran.

Layering points of sociopolitical and historical transition, documented in acts of small-press publishing, on to each other, the Warburg and Senate House exhibitions, in complementary ways, remind us of a critical history that is still unfolding. Both, too, in discrete fashion, provide welcome sources of inspiration for those deeply immersed or relatively new to these crucial practices. I would strongly recommend seeing them both together.

References

1. A list of the works on display at the Warburg Institute can be accessed here; the Senate House library exhibition works are listed here.

2. Michael Hampton, Unshelfmarkable, Reconceiving the artists’ book, Uniformbooks, 2015, page M.

3. Bookart Hermetics by David Mayor. In: Artists’ Bookworks, a British Council Exhibition, 1975, pages 70-87.

4. Arnaud Desjardin, stated in email correspondence with author, June 2025.

5. Michael Hampton, Unshelfmarkable, Op cit, page A.