,-2025.jpg)

Daphne Wright. Sons and Couch (detail), 2025. Jesmonite, Photo: Jed Niezgoda, Courtesy the artist and Frith Street Gallery, London and Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford.

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

13 June 2025 – 8 February 2026

by BETH WILLIAMSON

In the basement of Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum, at the very core of the collection displays, you might say, is a small exhibition by the Irish artist Daphne Wright (b1963). Working with unfired clay and jesmonite, Wright, who says she has an innate need to make things, has long-investigated the cycles of life, the transition of forms between life and death, the pivotal moments for human beings, especially her two sons. Through a variety of themes, what Wright comes back to again and again is the domestic, the place where identities are largely forged. This exhibition puts the domestic at the heart of the museum in language it understands. Of course, as Wright comments in the film made to accompany Deep-Rooted Things, the domestic is all over the museum. So, what is on show here?

Daphne Wright, Fridge Still Life, 2021. Unfired clay and mixed media, 132 x 48.5 x 52 cm on freestanding plinth. Courtesy the artist and Frith Street Gallery, London. Photo: Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford.

Fridge Still Life (2021) is a curious work in so many ways. A fridge, made of unfired clay, is mounted on a plinth in the gallery. This domestic appliance is, of course, used to keep food fresh for longer, to slow down the natural processes of life and death. Here, the door is missing, and I worry about the temperature of the items inside and that an uncooked chicken is above a bunch of wilting asparagus. Its shelves are quite bare, with just a couple of containers besides the items already mentioned. I can’t see if the vegetable drawer is full or empty. The artist’s sons on the couch adjacent have easy access to drinks and snacks, but there are slim pickings. On top of the fridge, a vase of drooping flowers gestures to the wilting asparagus inside and a 17th-century, Netherlandish flower painting hung nearby.

The centrepiece of this exhibition is a domestic scene, a tableau called Sons and Couch (2025). This is the latest in a short series of works that began with Sons (2011), then Kitchen Table (2014). Then on the cusp of adolescence, this latest sculpture sees them on the brink of adulthood. She laments the gaps in time between sculptures but she had to have their permission to cast them or it could not be done. Wright is clear that Sons and Couch does not portray her sons; rather, it is them, a solid rendering of a moment in space that captures them physically and emotionally as they negotiate their identities as young men. One son lies in a relaxed pose, stretched out on the couch, with plump cushions supporting his head at one end and an outstretched foot hanging over the edge at the other. He is outgrowing the domestic space physically and, by extension, emotionally. Wright’s other son sits on a rug on the floor, his back supported by the edge of the couch and his legs stretched out in front of him. The detail of the fringes on the rug, the lace edge of the tablecloth and the folds in his T-shirt are astonishing.

Daphne Wright. Sons and Couch (detail), 2025. Jesmonite, Photo: Jed Niezgoda, Courtesy the artist and Frith Street Gallery, London and Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford.

These young men may not be presented as athletes or heroes, but they still have much in common with the plaster casts in the museum’s Cast Gallery, which often take the young adult male as their subject. At the opposite end of this exhibition, we see a cast of the surviving fragments of a metope (a rectangular element of Doric architecture) from the Temple of Zeus in Olympia. A young, beardless Hercules defeats the Nemean Lion in the first of his 12 labours, at the very beginning of his journey through adulthood.

That same hairlessness is palpable in Sons and Couch. Xa Sturgis, director of the Ashmolean, observes a balance in Wright’s sculpture between vulnerability and brutality. While that vulnerability is obvious enough in her materials and in her tender handling of tableaux compositions – the poignant curve of a wilting flower, or the innocent air of the seemingly hairless bodies of two young men, eyes closed – the brutality emerges differently. The tableaux are largely drained of colour and pared back to their essential elements. The smoothness of surfaces such as heads and limbs recall childhood and the mother that soothed and cared for them when they bumped a head or grazed a knee. While this might be construed as a nostalgic remembering of care and care-giving, it might also be thought of as brutal, bringing such childish things back into plain sight just as these young men are navigating their way in the adult world and shaping their own identities. These lean young bodies are still growing into their own skin and yet, here they are placed in the public museum for all to see. It is not the bodies themselves but rather their emotional fragility that is exposed. There is an air of innocence in their closed eyes yet that is simply a function of the casting process. Meanwhile, the scale and placement and lack of colour lends it a monumentality akin to its Herculean companion.

Wright recalls visiting the homes of her children’s friends and sometimes seeing the cast pressing of a baby hand or foot, kept as a memento of that period in their lives and, she thinks, grieving for that past time. Her own experience of casting with her sons was gleeful and full of enjoyment. She recalls casting in bits when her sons were younger, an ear, part of a cheek, then putting the pieces together to cast the figure. The shift from kitchen table to couch comes with the increasing independence of the young men.

Daphne Wright. Ugg, 2019. Mixed media. Photo: Ellie Atkins, Courtesy the artist and Frith Street Gallery, London and Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford.

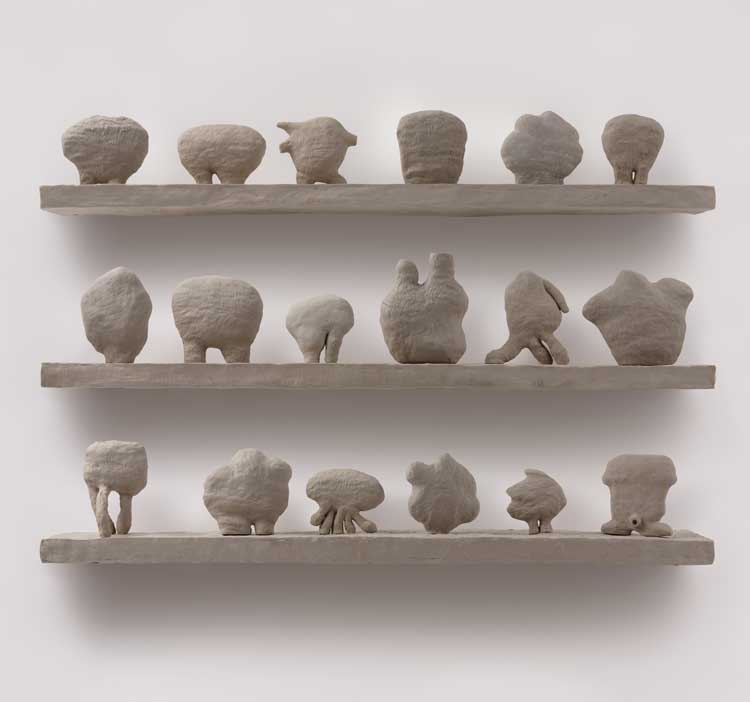

Further signs and symbols of the domestic and childhood adorn the gallery walls around this exhibition. The 18 amorphous objects that constitute Ugg (2019) could be a display of ancient artefacts, but it is not. Instead, it is based on a collection by the artist’s son of plastic figures known as Moshi Monsters. For Wright, however, they are perhaps presented as a relic of childhood and Ugg speaks to the childlike urge to build collections as much as the museum’s role in doing the same.

Daphne Wright. Pets, Amphibians and Reptiles, 2019. Mixed media. Photo: Jed Niezgoda, Courtesy the artist and Frith Street Gallery, London and Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford.

This idea of collecting is further explored in Wright’s series of works based on a collection of posters that once came free with the Guardian newspaper. Butterflies (2025), Pet Amphibians and Reptiles (2019), Pet Rodents and Rabbits (2019) and Dogs: Utility, Toy, Hound and Terrier (2025). Each collection in the series comprises around 30 or so wall-hung sculptures in greyish unfired clay. Butterflies is hung next to Rachel Ruysch’s A Forest Floor: Still Life of Flowers (1688) from the Ashmolean’s collection and featuring a red admiral butterfly among the flowers. Once again, Wright draws direct comparisons between the contemporary domestic landscape and that of the museum, a landscape that is broadened by her inclusion of Plates (2019) made by pressing clay between two plates and decorating the result with faded but familiar patterns. These ghostly remnants of years gone by speak to the domesticity of past childhoods and the future memories to be made in years to come. Wright often visited the Ashmolean with her sons when they were young. Now, on the brink of adulthood, they invite new audiences to experience her work and the collections within the museum.

Daphne Wright, Plate – Motif, 2019. Unfired clay and mixed media. Courtesy the artist and Frith Street Gallery, London. Photo: Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford.