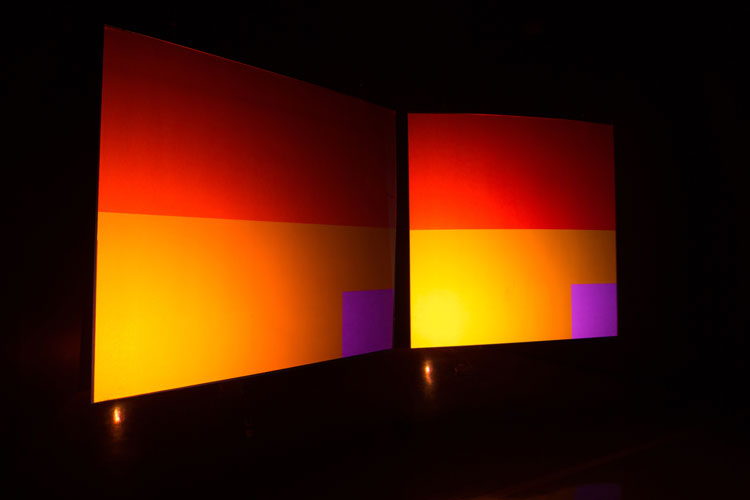

Ernest Edmonds, Shaping Space, 2012. Installation with computer, projector and camera. Private collection. Photo: Thales Leite.

by CAROLINE MENEZES

Ernest Edmonds (b1942, London) is one of the pioneers of what is variously termed computer art, digital art, or media art. An artist and mathematician, Edmonds has gained international recognition for his early and sustained exploration of human-machine interaction in the creative domain. His artistic projects, ranging from interactive installations, videos and art games to drawings and paintings, invite audiences to engage directly with algorithmic systems, offering insights into the dynamic interplay between people’s perceptions and actions and the potential for artistic experiments with technology.

The first time Edmonds used a computer to make art was in 1968 for the artwork Nineteen, when he wrote a program to generate an ideal image composition using numbers and shapes that he reproduced on canvas, prints and even sculptural reliefs. These rules still inform his paintings today. In the following year, he created the playful installation Communications Game, focused on non-verbal communication through minimal signals such as turning lights on and off, laying the groundwork for his interest in networked interactivity without prescribed instructions.

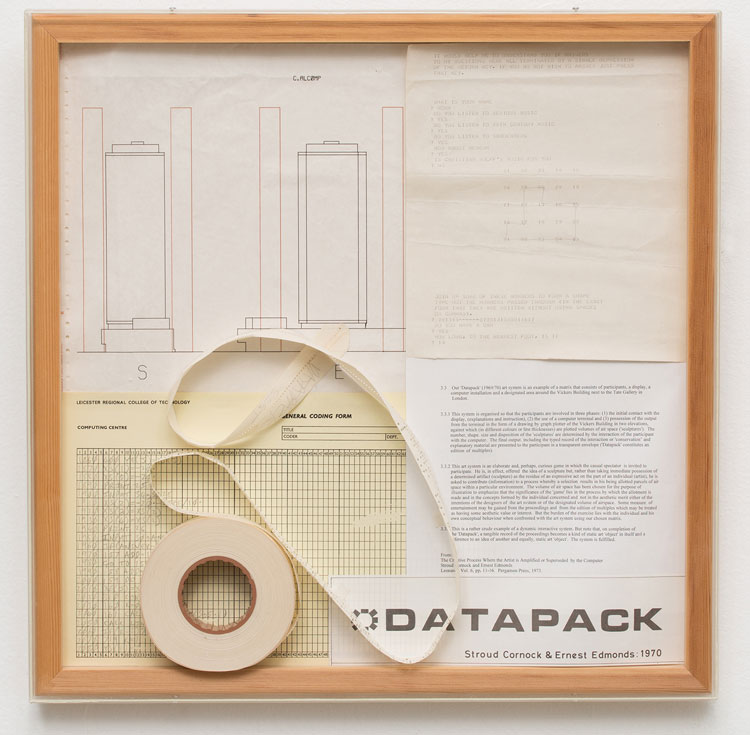

Ernest Edmonds, Datapack, 1970. Poster and punched card, 50 x 50 cm. Private collection. Photo: Thales Leite.

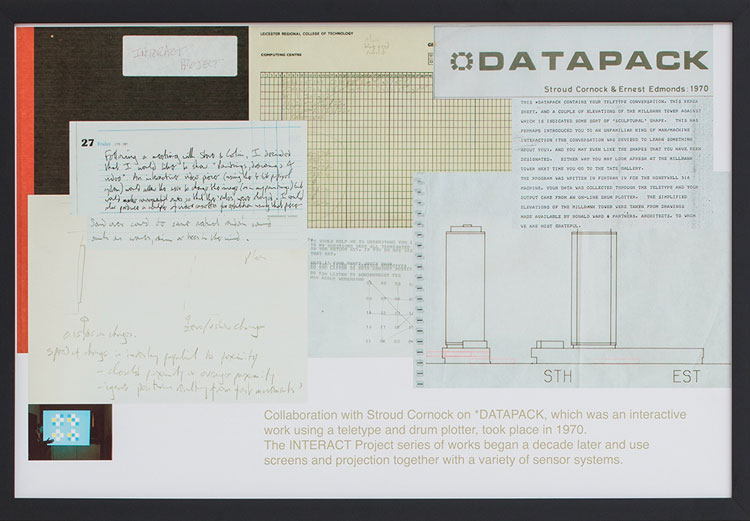

In the 70s, Edmonds expanded his practice across media, exploring film, sound and interactive systems. Datapack (1970) – created in collaboration with Stroud Cornock (1938-2019), a sculptor, curator and fellow pioneer of interactive art – enabled participants to have a “conversation” with a computer in English, with the exchange printed afterwards. Despite the limitations of early technology, the piece marked a key step in exploring interactivity in art, a concept that permeated his practice with series further on. This interest is evident in a range of works that progress with the digital transformation, starting from the 1990s and receiving different versions, such as the various iterations of Cities Tango, composed by a system that connects cities, allowing a person in one location to influence an artwork in another. Likewise, his Shaping Forms series, which features screen-based works that change shape and colour in response to the viewer’s movements, and Shaping Space, which offers an immersive development of that idea, extending the interaction into the surrounding environment.

Ernest Edmonds, Shaping Space, 2012. Installation with computer, projector and camera. Private collection. Photo: Thales Leite.

My connection with Edmonds began more than a decade ago, during my research into the early history of computer art, when I encountered his work and later met him in person in England. Later, I curated the exhibition Primary Codes, presented in Rio de Janeiro in 2015, which featured Edmonds’s work alongside pieces by other pioneers in the field: Harold Cohen (1928-2016), a forerunner of artificial intelligence and the arts; Paul Brown (b1947), a British artist at the forefront of generative art; and Frieder Nake (b1938), a German artist and theorist. The distinct visual language of each of these artists made significant contributions to the development of computer art. Their influence is vast, and over the past years, all have been honoured with the ACM SIGGRAPH Distinguished Artist Award for Lifetime Achievement in Digital Art,1 with Nake most recently receiving the award in 2025.

In July 2024, I encountered Edmonds in Germany during the Generative Art Summit, a conference that brought together an international group of scholars and artists to discuss the past, present and future of digital art. Held at the historic Akademie der Künste in Berlin, and framed by the comprehensive subtitle From Camera to Artificial Intelligence 1954-2024, the event inspired intense discussions on the fast-evolving relationship between computer technology and artistic practice.

Ernest Edmonds, Quantum Tango, 2025. Live interactive networked video connecting three cities: London, Vancouver, Padua. Webcams, Raspberry Pi and display screens, variable custom installation. Courtesy of Gazelli Art House. Photo: Deniz Guzel.

Between coffee breaks, Edmonds, his wife, Linda Candy (a respected researcher and author in creativity and practice-based research), and I deepen the debate, especially regarding the history of computer art. This interview continues a conversation that began in Berlin and is being published to coincide with Networked, an exhibition with Edmonds’ artworks at Gazelli Art House in London. The show is part of a collaboration with Francesca Franco, Chair of the SIGGRAPH 2025 Art Gallery, who is leading the curatorial vision for this year’s edition, focused on the dynamic interplay between nature, art and technology. Edmonds’s new interactive work, Quantum Tango, will be on view simultaneously at Gazelli Art House, at the 2025 SIGGRAPH conference in Vancouver, and in Italy. The three locations are connected via live data and video streams, enabling participants in each city to shape the evolving composition across the network.

Ernest Edmonds, The Communication Game, 2025. Arduino microcontrollers, toggle switches and LED ligthboxes presented in custom-built booths. A new version of an ongoing project, begun in 1969, variable custom installation. Photo: Deniz Guzel.

In a time marked by heated debates surrounding computer-assisted creativity, generative processes and the role of AI in the arts and creative industries, speaking with a pioneer of algorithmic and interactive art felt urgent and timely. With computer art finally entering the mainstream art discourse, the opportunity to reflect with someone who helped shape the field from its inception was invaluable.

Caroline Menezes: The last time we met was at the Generative Art Summit, held in Berlin last year. There, we shared a slightly uneasy feeling about seeing the current generation of artists working with code being called pioneers, while you, Frieder Nake, and other true pioneers were there and were already doing art in the 1960s. How do you see the current state of computer art? Beyond the obvious technological advancements, I sometimes feel that we need more historical exhibitions to show the younger generation that many of the provocations around the “partnership/association” between computers and creative minds were already being explored from the very beginning, conceptually, as in your earlier works such as Datapack and Communications Game, and also aesthetically. If you had to advise the new generation on the next step in creative technology and making art with computers, what would it be?

Ernest Edmonds: In view of the massive changes in technology that have taken place since I started (1968), younger people may have difficulty in grasping what preceded them. There is nothing new about artists studying the history of their medium, however. A problem is that generative, digital art is only just now being accepted in the established art world and so that history is not readily available yet. I agree with you that we need to raise its profile. As in all forms of art, we can find good and bad, innovative and pedestrian. Computer art is no exception. But, because it is a relatively new medium, the pedestrian is almost as accessible as the exciting work. However, the lack of grounding in history is quite a weakness. My early work that you mention provides a good example, including the related publications. Consider just the title of the paper Stroud Cornock and I presented in 1970, The Creative Process Where the Artist Is Amplified or Superseded By the Computer.2 We were clear that the way forward was with the technology as an amplifier, and that is still the case. But it is not uncommon even today for people (artists? technologists? …) to think that computers can make art of quality: replacing the artist. Strangely then, my advice today is partly the same as it was 55 years ago. Ask questions. What is the special nature of the latest technology, used as a medium for art? Is there something to add to colour, form, time, interaction etc that art using the new technology is characterised by? And, to repeat from the past, how can it amplify your creativity?

Ernest Edmonds, Nineteen, 1968/69. Constructed wood relief, 183 x 145 x 18 cm. Private collection. Photo: Thales Leite.

CM: What inspired your interest in making art? And how did your fascination with computing begin? When and how did the spark happen that led you to think of using computers in your art, such as in Nineteen? When you first saw the process in action, a computer generating patterns for creating drawings, did you have a sense, even then, that this could the future of art? Or did you see it more as just one of many possible tools, perhaps a way to make computation more appealing?

EE: My interest in art, initially drawing, started when I was about 10, but the striking moment came while I was in secondary school and saw a Cézanne self-portrait. Like most artists, I explored many avenues before focusing on the constructivist tradition, tempered by a continuing fascination with Cézanne and a strong concern for colour inspired largely by Matisse. I also came to know Kenneth Martin and the UK Systems Group. This was a natural starting point for the exploration of computation, the implications of the computer for art. The actual start for me was while making Nineteen. It consisted of 20 reliefs, but my initial concept did not consider how they were to be arranged, except that they would be in a 4x5 grid. When I came to look at that issue, I found it quite difficult to resolve. I could see that certain pieces should not be close to one another, others should not be on the same column, etc, and, as I had just taught myself to program a (mainframe) computer, I realised that I could write a program specifying those rules and setting a process going to search for a solution. So, in 1968, I found that computers could be valuable in my art. It was the same year as the Cybernetic Serendipity exhibition, of course. The Computer Arts Society was formed and, I started collaborating with Stroud Cornock. That is when my real artistic journey began.

Ernest Edmonds, Datapack, 1970. Notes. Private collection. Photo: Thales Leite.

CM: You were also one of the thinkers who introduced the idea of interactivity between machine and art. And by interactivity, I mean works such as Datapack, where a computer was answering questions, anticipating what is now common with chatbots and machine learning. What compelled you to explore that further?

EE: In the late 1960s, participation was a fashionable concept in art, so realising that computers were developing in the direction of enabling human-computer interaction (rather than requiring punched card or paper tape input and line printer output), interactive digital art looked like an important way forward to explore. The technology didn’t make it easy at the time, but it was clearly right for the future. Very soon, Xerox Parc would open, and personal computers would start to appear. The technology of the artwork Datapack was primitive by modern standards, but it absolutely engaged people in an interactive aesthetic experience.

CM: How did the relationship between human and machine evolve in your work, and how did that develop into the series exploring the interaction between the public and the artwork?

EE: As soon as I realised that interactivity was a key area for computer-based art, I saw that very little was known about what we now call human-computer interaction (HCI or sometimes CHI) outside art, let alone within it. Hence, I then promoted research into the subject, and it grew to become a second string to my bow. So, in parallel with my art practice, I developed a programme of research into HCI, and the two fed off one another.

,-2014.jpg)

Ernest Edmonds, Four from Shaping Forms (Park Hill B), 2014. Acrylic and digital print on canvas, 150 x 150 cm. Private collection. Photo: Thales Leite.

CM: How crucial do you think it is to understand coding in order to create art with new technologies? Do you see it as a decisive skill that artists must learn themselves, or is it something that can be outsourced?

EE: It rather depends on how the artist is working. If they are using a computer application, such as a painting system, then they may only need to understand how that application works. On the other hand, if, like me, the artist is exploiting software as a new medium for making art, making new forms of art, they need to understand software. The code is important, and its characteristics will matter in the art-making process. For us, as software artists, understanding coding is vital. Even if the artist subcontracts some of the coding to a programmer, they will need to know how to do it themselves, or they will be giving a portion of the creative decision-making away, which is OK if that is what they want to do, but it’s not for me.

CM: Do you think that, due to its technological essence, collaboration among digital artists has become something intrinsic to what we call digital art? Following this idea, could the subjectivity of the artist become less prominent in this kind of artistic expression? Does computer art deal more with universal or abstract concepts, rather than personal ones?

EE: I am not sure that collaboration is any more important in digital art than in other media. For example, in silk screen printing or bronze casting, it has often been important and, of course, for a very long time, artists’ studios have been partly occupied by assistants who did some of the work, even though the lead artist was perfectly capable of doing it should they have wished. As to subjectivity in the digital arts, we can think of an artwork, from the artist’s point of view, as existing in a set of layers. For example, one layer might be a mathematical structure such as perspective, another might be colour laid down on top of the perspective, then perhaps texture. One way of looking at this example would be to see the most subjective part as the texture and the least subjective as the perspective. The choice of using perspective, and the form of perspective, can be seen as subjective, as is the texture. So, in digital art, many of the choices made about the “abstract concepts” being used will be quite subjective, while what follows applying them can be seen to be “universal”. In that sense, what you suggest is often true, ie, “computer art deals more with universal or abstract concepts, rather than personal ones”. But we should not forget that some artists use computer painting systems that imitate freehand drawing, and naturally, they work as subjectively as anyone.

From left to right: Ernest Edmonds, Shaping Form 28.5.2007, 2007. Computer, monitor and camera. Private collection; Shaping Form 28.10.2013, 2013. Computer, monitor and camera. Private collection; Shaping Form 1.5.2015, 2015. Computer, monitor and camera. Private collection. Exhibition view, Primary Codes), Rio de Janeiro, 2015. Photo: Thales Leite.

CM: From the current wave of advanced creative technologies, AI, virtual reality, augmented reality, is there any specific one that has caught your attention?

EE: Well, I have been working with all those examples for many years, although AI has taken on a new meaning in recent times, referring to just a small (but successful) special area of AI as I know it. My current focus is in the area of quantum computing, with its fundamental concern for uncertainty. While standard computing simulates randomness with pseudorandom numbers, quantum computing has true uncertainty at its core. Now that is an exciting area to consider, and although the fundamentals were understood quite a long time ago, the implications are only now being investigated. The other area, which I started looking at in 1970 but am working hard on today, is communications. The full development of network art as a new form still has a long way to go.

CM: To wrap up, could you tell me about your current artistic projects?

EE: It is quite a busy time, I am pleased to say. I am presenting the next piece from my Cities Tango series, where several interactive works communicate with one another over the internet. These integrate changing, reactive, abstract images with photographic images from the various cities involved, some caught in real time. The main driver is an invitation to contribute to the art exhibition at the 2025 SIGGRAPH Conference.3 The Art Exhibition Chair, Francesca Franco, invited me to make one of my networked distributed pieces. I am showing a new one, Quantum Tango, that has three interacting parts, Vancouver, Padua and London (at Gazelli Art House). This year’s SIGGRAPH art theme, “Connecting Nature, Art and Technology”, has shaped the photographic element of the new work. For example, tree growth in London is creeping through and changing fences, or fires near Vancouver are reshaping the landscape. The Quantum aspect of this is about moving from standard two-valued logic, which has played a part for a long time, to quantum logic. But that is another discussion. It’s great that Gazelli is presenting innovative digital art in the heart of London’s commercial scene. Quantum Tango is being shown at Gazelli alongside a reconstruction of my first networked art piece, Communications Game.

References

1. The Association for Computing Machinery (ACM) is an international scientific and educational society dedicated to computing. SIGGRAPH stands for the Special Interest Group on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques.

2. Later published as Cornock S and Edmonds EA, The Creative Process Where the Artist Is Amplified or Superseded By the Computer. Leonardo, 6, 1973, pages 11-16.

3. The very large annual computer graphics conference that has featured computer-based art since 1981.

• Ernest Edmonds: Networked is at Gazelli Art House, London, until 6 September 2025, to coincide with the SIGGRAPH 2025 Conference in Vancouver, Canada, from 10 to14 August.

Ernest Edmonds. Courtesy of Gazelli Art House. Photo: Deniz Guzel.