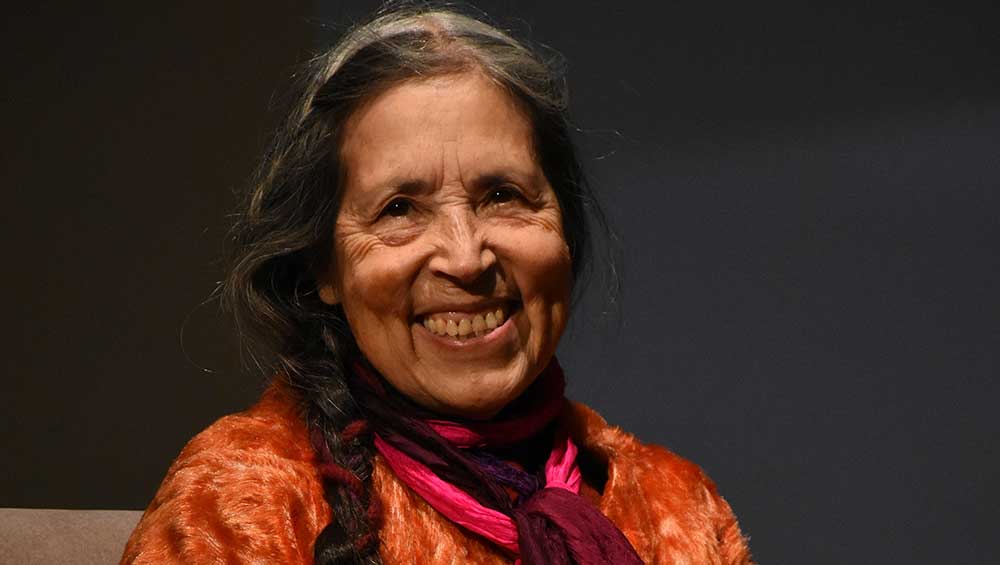

Cecilia Vicuña. Photo: Bruno Savelli.

Interview by VERONICA SIMPSON

There was a moment in 2022, as we emerged from two years of pandemic lockdowns, when museums, galleries and streets were once again filling with people, curious and hungry for connection, eager to feel that the world they were emerging into, after having gone through so much, might be not just different but better. That optimism crystallised for me at Tate Modern that autumn. Here, in this icon of contemporary culture, this symbol of extractive, industrial Britain, was a major retrospective of Magdalena Abakanowicz, whose giant, sumptuously coloured textile structures offered a celebration of the animal, specifically female form, from vulva to womb, which felt as if it could rebirth us all. Alongside this, a giant installation filled the Turbine Hall from the poet and artist Cecilia Vicuña (b1948, Chile). Brain Forest Quipu was encountered as a soundtrack first: from the moment you walked into this vast space, the air filled with the sound of singing, of chirruping – birds, animals, humans in the rainforest, created with Colombian composer Ricardo Gallo. Two sculptures of knotted textiles were draped from the Tate’s ceiling. They were made from organic materials including found objects, unspun wool and plant fibres. The exhibition evoked the ancient South American practice of collectively creating a quipu – a communication system made from knotted threads, using memory objects to record history, ownership and events. Any such artefacts found were destroyed by the Spanish Conquistadors as soon as they realised that they presented an alternative, indigenous history. Vicuña’s wall text declared: “The Earth is a brain forest and the quipu embraces all its interconnections.”

.jpg)

Cecilia Vicuña: Reverse Migration, a Poetic Journey, installation view, IMMA, Dublin, 7 November 2025 – 5 July 2026. Photo: Ros Kavanagh.

Now in her late 70s, Vicuña has been making these quipus for decades, celebrating the fragility and connectivity of plants, animals and people while protesting eloquently the governments and systems who seek to destroy these connections. Raised in what was a quiet village on the edge of Santiago – now part of its sprawling suburbs – as a young woman, Vicuña witnessed and supported the election of Salvador Allende’s socialist party. But she was in London, studying at the Slade School of Art on a British Council scholarship, when his brief, three-year reign was extinguished by a CIA-backed coup led by General Augusto Pinochet. Thus, she suddenly became an exile. She continued her studies in the UK, then moved to Colombia, and then to the US, living in New York. Her political and artistic passions have continued undimmed, and her work has gained increasing prominence, recognised in a retrospective at Rotterdam’s Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art (now the Kunstinstituut Melly) in 2019 and then earning her a Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement at the 2022 Venice Art Biennale.

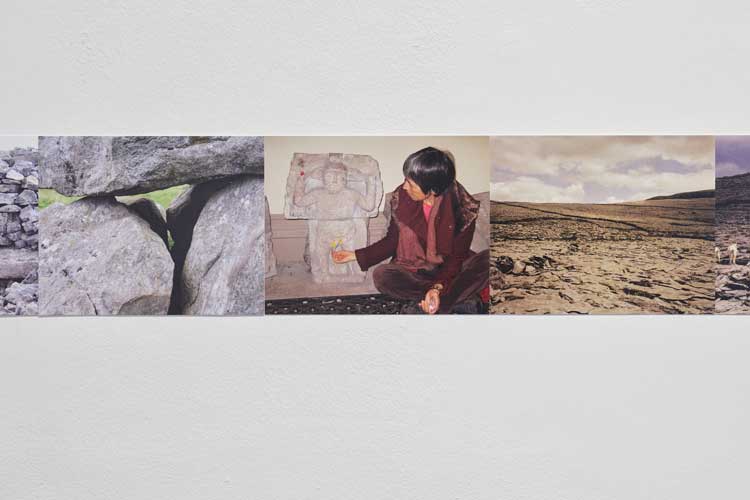

Cecilia Vicuña, A Poetic Journey in Northern Ireland, 2006. Courtesy the artist. Installation view, IMMA, Dublin, 7 November 2025 – 5 July 2026. Photo: Ros Kavanagh.

For her current show, at the Irish Museum of Modern Art (IMMA) in Dublin, Vicuña brings to bear all her skills, as poet, painter, protester and weaver of stories and quipus. A quipu made with local artists (Foraging Quipu, 2025) opens the show. Then we delve into her early years, photographs from her early art school projects of 1969 and 1970, when she was part of a Santiago-based group of artists and poets, protesting against the Conservative, pre-Allende regime. So much of Vicuña’s early work was lost or destroyed that she has had to recreate it, including an illustrated cover for a poetry catalogue of 1970. There is documentation from her London years when she founded Artists for Democracy with David Medalla, John Dugger and Guy Brett. There are several of her “Palabrarmas”– drawings, collages, banners, videos and performances exploring the role of poetry and art in turbulent times, some from her time in London, others made in Bogotá, to which she moved in 1975 – Colombia then being one of few South American countries that wasn’t under military dictatorship at that time.

,-1980,-courtesy-the-artist.jpg)

Cecilia Vicuña, Que es para usted la poesía (What is Poetry to you), 1980. Courtesy the artist. Installation view, IMMA, Dublin, 7 November 2025 – 5 July 2026. Photo: Ros Kavanagh.

There is a moving and entertaining documentary she made in 1980, in which she roamed the streets of Bogotá asking people what poetry meant to them. The responses were almost universally enthusiastic and articulate, whether she was speaking with a car mechanic, a sex worker or salsa dancers. The way the responses are woven together creates a unique form of visual and verbal poetry.

Taking up a large chunk of IMMA’s longest corridor is a ghostly, spellbinding “Aran Quipu”, made of local sheep’s wool, accompanied by a wall poem in Vicuña’s distinctive spidery handwriting:

“Aran Quipu exists at the edge of the impossible. Nothing holds it together except the desire of each fibre to hold on to the next. This quality makes unspun wool sacred, as it contains all possibilities. For me it symbolises the ‘gluon’, a particle that carries the strong force … because it so tightly ‘glues’ quarks together into larger particles. Perhaps one day we will see this cosmic desire for togetherness as what connects us all.”

The official wall caption tells us: “Drawing on the symbolism of the Aran sweater, with its deep ties to nature, the sea and island life, this large-scale installation becomes a powerful meditation on survival, transformation and collective action in the face of global ecological crisis.”

We are encouraged to weave through and around this quipu, waltzing to a spectral soundscape emanating from a neighbouring room. Here, Vicuña has made Mourning Dialog, a sound piece of her own, ethereal, chanting voice, duetting with a wildlife recording (by the ornithologist and writer Seán Ronayne) featuring the curlew, a wetland bird that has all but disappeared from Ireland. This room, painted a deep, malachite green on three walls and ceiling and black on the fourth wall, offers comfortable beanbags on which to sit and reflect on disappearing wildlife and icebergs.

Sheela-na-gig, Sier Kieran in Co, Offaly, 13th-17th century, on loan from National Museum of Ireland. Installation view, IMMA, Dublin, 7 November 2025 – 5 July 2026. Photo: Ros Kavanagh.

Subsequent rooms contain all new works or early works recreated in recent years. They include a room cataloguing the journey of Vicuña and her partner, the American poet James O’Hern, around the ancient sites of Ireland, communing with ancestors, after discovering they both shared DNA from the Oisín clan in the north of Ireland. In the subsequent room is a medieval sheela-na-gig (a stone carving of a woman with an exaggerated vulva) from between the 13th to 17th century, loaned from the National Museum of Ireland, accompanied by sublime and celebratory oil paintings by Vicuña of other Sheela-na-gigs and symbols of female power, including her own “self-portrait”, Sheela Cec (2024). In the following room are what the artist terms The Assistants, small paintings, “conceived as ‘prayers’ – quiet invocations for the continuity of life’s beauty and complexity on Earth”.

Cecilia Vicuña, Ceremonial dress. Courtesy the artist. Installation view, IMMA, Dublin, 7 November 2025 – 5 July 2026. Photo: Ros Kavanagh.

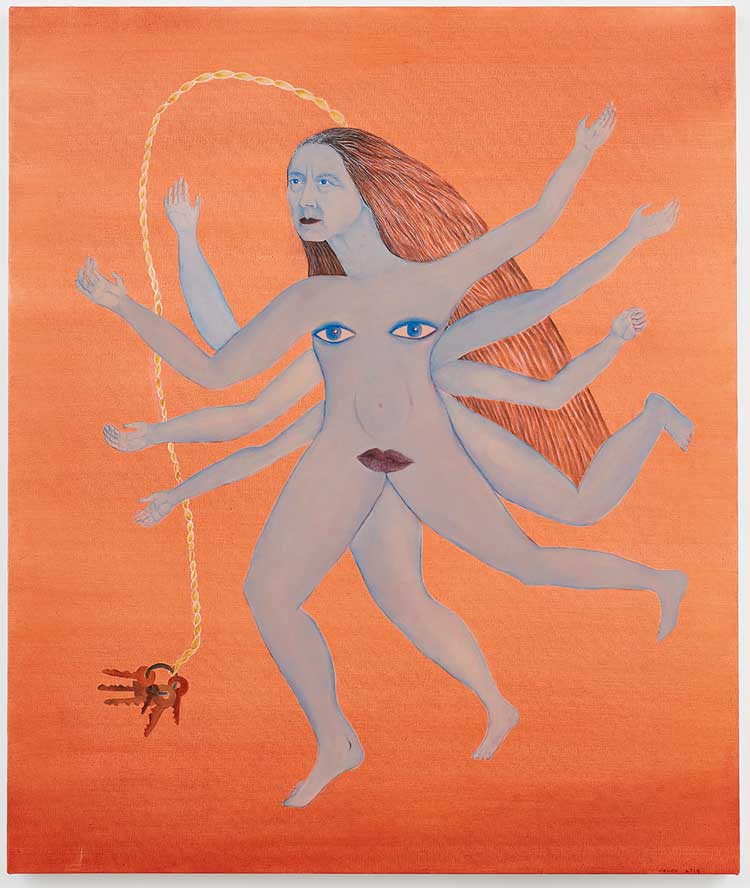

Another textile of delicate, collaged material is draped across the following room, called Unku, Ceremonial Dress. An unku is a poncho-like garment, worn by the Inca for ceremonies. This one, created from salvaged fragments, becomes, in Vicuña’s words, “a dress for all and no one, an array for the oneness that survives our brokenness”. The next room celebrates “feminism and mythology”. Works by Vicuña are placed in conversation with the surrealist artist Leonora Carrington. Most of the paintings are recreations of works Vincuña first made in London, inspired often by her rapt encounters with pre-medieval art in the National Gallery, but with a feminist twist. Some of these were shown in her segment of the Venice Biennale, such as Chinnamasta (2021) and La Comegente (The People Eater) (2019), after the original, lost 1971 work. The last room – but one of the most entrancing – is like a glowing shrine, its painted white walls filled with Vicuña’s Precarios, poetic assemblages of organic and cast-off detritus. I can’t imagine a setting in which the upturned lid of a yellow paint pot could look so magical.

I meet Vicuña, 77, diminutive but radiating energy, in person, at the opening of her IMMA show.

Veronica Simpson: I believe you have a story for me about Studio International.

Cecilia Vicuña: I arrived in London at the end of September 1972, on a British Council scholarship and, at some point, I met Peter Townsend, the editor of Studio International. I believe it was through Monica Pidgeon, a great architect who was director of a magazine called Architectural Design. She published a little note with photographs of a mural I had painted in the streets of London. I believe it was through her that I met Peter Townsend. When he heard that I was the co-founder of Artists for Democracy, he offered the offices of Studio International as our meeting point. We had all our first meetings of Artists for Democracy courtesy of the generosity of Studio International. Very few people know this.

VS: I read somewhere that you had originally intended to study architecture.

CV: Yes, I entered architecture school, a very difficult admissions process. You had to be in the top echelon, achieved with something like a medieval baccalaureate. I believe I was the last generation that went through that process. I was admitted and was there for three months and then I realised the vision I had for architecture was (more akin to what’s happening now, now that architecture is returning to the earth) using earth materials and considering architectural creation more as an artwork that involves in its creation different kinds of society, allowing for exchange, for participation, for community. I had all those ideas in the 1960s when I graduated from high school – could be 1966 when I was in architecture school. The University of Chile, where I did my training, was completely involved in social architecture, which meant square buildings for people with low incomes. There was no room for anything else because this was an urgent issue for Chilean society at the time, so I was better off going to art school.

Cecilia Vicuña, Precario, installation view, IMMA, Dublin, 7 November 2025 – 5 July 2026. Photo: Veronica Simpson..

VS: Had you already started making your “spirit houses” then, little structures made from salvaged parts?

CV: Yes, you see my Precarios work began between finishing high school and starting architecture school. If you look at them, you see they are architectural constructions more than sculptures. What inspired me was when I was about 11, my father, who had an absolute love for art, showed up at home with a big book on Pablo Picasso, by Jaime Sabartés, an art historian. My family was convened around the coffee table where my father would lift each page. That was how it was communicated to me, the sacredness of art. Instead of reading the Bible, like other families, we would be reading an art book. There were photos of the studio of Picasso, with a lot of rubbish and things thrown about. And I liked that rubbish more than I liked the art. And on the mantelpiece there was a series of little sticks and things that instead of going to the floor were … abandoned there. And I looked at them and thought, how wonderful. That is where I picked up the idea that rubbish was a fantastic material.

And you know I abandoned that (practice) in Chile, but when I arrived in London, my response was doubled. On the one hand, I started to go to the National Gallery almost every day to look at the Italian pre-Renaissance paintings. I had only seen those reproduced in books and usually in black and white, so I was completely blown away by them. If you look at the paintings I did in London, there is a distortion in the figures, which was in response to that. On the other hand, I spent my life in London day and night walking the streets, picking up debris. There was lots of fantastic debris. For example, there were lots of garment factories throwing out bags of fur scraps, bags of velvet and Liberty print cotton on the sidewalk. Those Liberty prints ended up becoming part of my Precarios, with fur and velvet and all those things, as well as metal and all kinds of industrial debris.

While I was in London, I saw the film State of Siege (1972), directed by Costa-Gavras, which had been filmed in Chile and was about the military coup in Uruguay. The premier was at the Chilean embassy, and I was invited. Many of my friends were extras in the film – because I had friends in theatre school in Chile. And this horrendous dictatorship was represented in the streets of Santiago. I understood then that this was not a film, but a representation of what was about to happen in Chile. And I started to cry desperately. People were saying: “Why are you crying, it’s a wonderful film, we are here to celebrate Costa-Gavras. Why are you crying?” And I said: “Because this is going to happen.” Nobody believed it. That’s when I started my journal on Chilean resistance. (The military coup in Chile happened on 11 September 1973.)

Brujo-Rojo,-Brujo-Celeste,Brujo-Polpo,-Tierra-Negra,-Celia-Vecuna,-1966-2023,-courtesy-the-artist.jpg)

Left to right: Brujo Rojo, Brujo Celeste, Brujo Polpo, Tierra Negra, Celia Vicuña, 1966-2023. Courtesy the artist. Installation view, IMMA, Dublin, 7 November 2025 – 5 July 2026. Photo: Ros Kavanagh.

VS: I had what I hoped was a sense of optimism and the feeling that change was in the air when I saw your show at Tate Modern in 2022, alongside Magdalena Abakanowicz. It was a shock at the time to realise here were two women who had been making significant work for such a long time but had been allowed to fall below the radar for decades. I was stunned, and also curious about how that happened. It’s a topic I raised with the directors of Haus der Kunst in Munich when they showed an exhibition on installation art and all the most significant artists of that time were women. And yet in the interim – until they started doing their research – nobody had realised this. They had to recreate half the exhibits, because nobody had stored or collected or archived them. How do these acts of erasure happen?

CV: That story on installation art, I lived that story too. I did my first one-woman exhibition at the National Museum of Fine Arts in Santiago. I filled one huge room with autumn leaves. I brought the autumn inside. Do you think I had heard the words conceptual art? No, I had not. I knew nothing about women mostly doing these kinds of things all over the world. Most people who did it in Japan, or Germany, were also, like me unaware. It took 30 years for that installation, that I created in Santiago in 1971, to be mentioned in one phrase in a documentary, by a man.

VS: But you were not making this work for posterity.

CV: No. I was doing it for the awareness for Chilean citizens. To celebrate socialism. This exhibition meant for me the awareness of the joy of now. If we understand that we’re going to die so soon – 70 years was the life expectancy at that time – we have to have a revolution for joy, because we need to be joyful. So, that was my proposal.

And it took half a century for someone … a Chilean curator invited me not to recreate the whole installation, because the museum didn’t have that capacity, but to have a room in a museum with photos. This was in about 2005, nearly 50 years later.

Cecilia Vicuña, Llaverito (Blue Lady) / Ladilla, Crab, 2019. Oil on canvas. 109.22 x 91.44 cm. Private collection. Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Seoul, and London. © 2025 Cecilia Vicuña.

VS: It must feel good now to be properly recognised, after the Witte de With retrospective, and the Golden Lion. How do you feel about this appreciation of your work, after all this time?

CV: No, I never think like that. I grew up in Chile. There have been artists in my family for three generations, and some of them were persecuted. Nevertheless, they continued doing art until they died. Nobody had the expectation before me to be acknowledged. I never heard that. There was never any frustration. What was communicated to me was the absolute reverence and dedication to art, as a magnificent way of being. I grew up with this idea. The fact that they ignored me, repressed me, censored me, seemed absolutely normal. And I didn’t dedicate two seconds to thinking about it. In the history of poets and artists in the world, this has been the norm. This idea of expecting to be recognised, it began in the 1980s, when the art market intervened. Before then, I don’t think I was unique in this notion I’m telling you. Most artists didn’t think they needed to be recognised.

Of course it’s fun, it’s beautiful, it’s miraculous, I am happy about it. But I don’t give it a lot of importance. I think what matters is this shift in consciousness of society itself. So, if I have to play a part in that, I’m happy. Though what is now really terrible is that, just as we are speaking … of women’s imaginations becoming stronger and stronger, the systems of control have developed cell phones, screens, AI, and this is controlling the minds, the imaginations. That is a threat to the survival of humanity. Now the threat is existential, it’s not about the oppression of women, it’s about the survival of humanity.

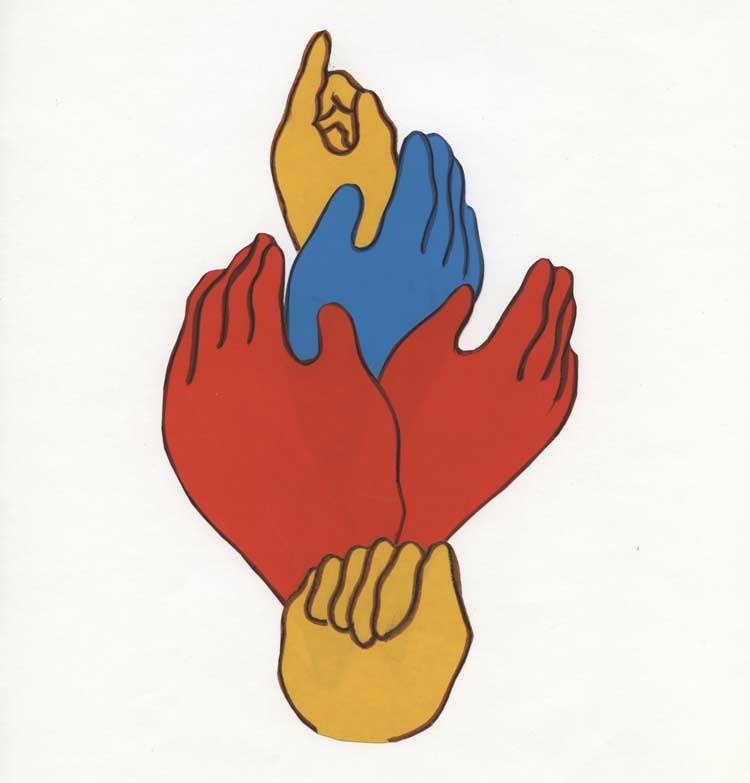

Cecilia Vicuña, Arból de manos, 1974. Collage on paper, 30.5 x 23 cm. Private collection. Courtesy of the artist. © 2025 Cecilia Vicuña.

VS: For someone so attached to and in tune with nature, it’s interesting that you have chosen to live in New York.

CV: When you are an exile, a refugee, you don’t choose where to be. No refugee chooses. The refugee tries to survive that’s all. In New York I found a refuge. Now that refuge is in question, because of the new reality, the new law.

VS: I truly sympathise. But here you are in Ireland, a place that means a lot to you. The curator, Mary Cremin, said when they approached you in Rotterdam to bring that retrospective here you said you wanted to make a special show for Ireland. Why is that?

CV: Yes, because I met Jim, my partner (James O’Hern), in 2004. He gifted me my DNA. He had done it through Oxford Ancestors, a scientific institution run by a geneticist, Bryan Sykes, which had devised a technology whereby you would get a little kit and send a sample of your saliva and they gave you back a 140,000-year history of the journey of your genes. And the last mutation was the point of origin. My paternal lineage was the north of Ireland.

Then Jim invited me to come here. We took a journey, represented in this show as the Poetic Journey, through ancient sites. He designed this journey through sites that were at least 5,000 years old. I had the experience of staying in the neighbourhood for each one of these sites for several days: we spent a month here just doing that. I had the feeling in my heart, the profound impression of these spaces speaking to me. I felt at home. For the soul, time does not exist. In this period, art and poetry are not limited by time. They exist in another time. And, therefore, when I was invited by IMMA, I knew I wanted to tell that story, but in art and poetry. This was not the place for a retrospective.

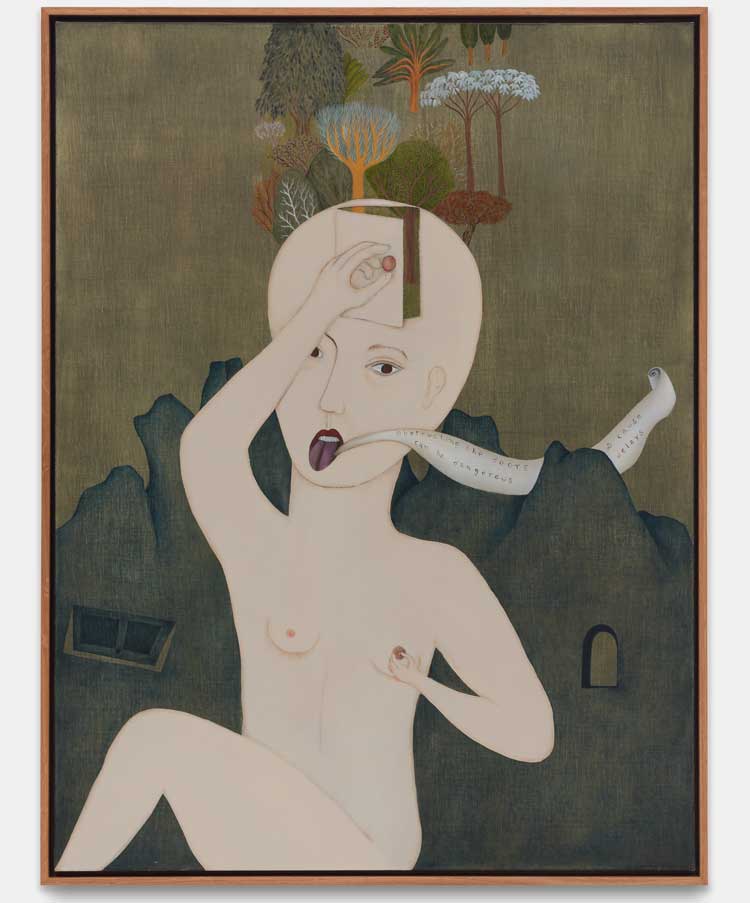

Cecilia Vicuña, Obstructing the Doors is Dangerous, 1972/2023. Oil on canvas, 101.6 x 76.2 cm. Private collection. Courtesy the artist and Xavier Hufkens, Brussels. © 2025 Cecilia Vicuña.

VS: But you have produced such an amazing body of work in the last two years, judging by the paintings and Precarios that fill these rooms. I read that you stopped painting from 1998 until 2013.

CV: When I stopped painting, I knew that I would go back to painting as an old woman. I didn’t stop because I didn’t like it. I always loved it. My mother says I was painting before I could speak. I was drawing, but for me drawing and writing are one. To this day, I handwrite all my work. I am always handwriting, so some of my books are a form of poetry that is a form of drawing at the same time. Art, painting and drawing for me are really one.

VS: There are also films here, where you ask people in Colombia what poetry means to them. I am amazed that ordinary citizens are so eloquent on this point – or they were in the 1980s.

CV: That tells you a lot about the system that has managed to do away with poetry. I made that film in 1980 and, for me, it was evidence that people still lived in the oral culture. Most people were able to do an elaborate, philosophical speech without education – that means they had conversations with their friends, with each other, that were intelligent and complex. This was before people’s lives were ruined by cell phones, by the computer, which uses up the mind space, so complex conversation has practically disappeared from the family situation. This was where and when people spent time with each other, hearing each other. That has disappeared.

.jpg)

Celia Vicuña, Prayer for the Rebirth of Peace in all lands, 2024. Courtesy the artist. Installation view, IMMA, Dublin, 7 November 2025 – 5 July 2026. Photo: Ros Kavanagh.

VS: Well, Ireland might be one place where poetry still lives in the mainstream imagination.

CV: I agree. To me, all peoples are indigenous – except some have forgotten and pretend that they are superior, because they are white or for this or that reason. But even communities in Scotland are indigenous. And so are the Irish. I connect with indigenous, native Irish culture … When Catherine Connolly was elected as Ireland’s president, I felt that energy coming back. She gave a speech about the creativity of women that was so incredibly beautiful. I thought how many women leaders in the world today speak that way, honouring the ancestral lineage of creativity in women that … needs to wake up to reorient humanity.

VS: I couldn’t agree more. And I love the way you have taken this opportunity of the exhibition here to explore the sheela-na-gig sculptures of Ireland, that ancient symbol of birth and femininity. How did you come across these?

VS: I had heard of sheela-na-gigs, the history, but never seen one. In May, IMMA invited me to come to the National Museum, where I saw it (the Seir Kieran, County Offaly sheela-na-gig, which also features in Vicuña’s show). It was the first sheela I had seen in person, and – in Spanish, we say, “she dissolved me” – she demolished me completely. And I began to paint. Between May and now, I did nine sheelas.

VS: This show seems to have sparked a surge of creativity.

CV: You see. When I grew up, I think I was very lucky as my mother is an Indian, but I didn’t know she was an Indian. I only realised when I did my DNA. So, what was my mother like when I was young? She has a sense of joy. And joy is like her thing. She has this force, this attachment to life. Where is this fierceness? I was born in a little adobe house in the wilderness that was countryside but is now part of Santiago. There were no electric lights in the street. My mother was a fierce organiser, she talked to everyone, she organised to get streetlights, and then to have trails converted to something like a road. Always in the mould of joy and connection and loving and making fun. And all this serious intellectual family that was my father’s side despised her, and she responded with kisses and embraces. She would not be oppressed – by her own feeling about herself – nor despise her own possibilities.

VS: Lastly, can you tell me about the major new quipu in this show – Aran Quipu. Here, you have made it with Irish wool, working alongside Irish textile artists. But unlike the one in the Turbine Hall, which was knotted skeins of wool, these are creamy sheets of wool. If there are knots here, they are very subtle, almost invisible.

CV: What makes good wool is the happiness of the animal. It has good grass, this reflects in the quality of the wool. This is the material that I need. That’s why I make my quipu out of unspun wool: it translates to a different kind of relationship to the land. In Ireland, my greatest joy about this installation, is this discovery (of Galway Wool Cooperative). I learned that Irish wool has disappeared, but through IMMA I found an Irish provider of Irish sheep wool from a breed that is about to go extinct. There are only 1,000 females left. We found a small co-op, and they are trying to bring back the value, the significance of Irish wool. The quipu provides a purpose.

I don’t need the knots. I make quipus with knots when they are very tall, because otherwise unspun wool will break. So that’s why, for example, the quipu we had in the Tate had knots, because it was created to be more than 10 metres tall. Your perception that there are knots in the unspun wool is true. In the poem that accompanies the installation, I speak about the fibres sticking together of their own accord. The energy of the cosmos is in there, as it is in us.

I work with assistants. I instruct them on the transparency and thickness. The work begins a few days before I arrive. And then I begin putting it up. I have assistants working with me. Because the quipu needs two things, it needs a group of people and it needs a ritual. So, it begins with a ritual of … flowers and songs and the unity of people, the prayer to become one with the quipu for the quipu to do its work. It’s not an object. It is a structure of thought and feeling and action. It is an instrument for the preservation of life.

• Cecilia Vicuña: Reverse Migration – A Poetic Journey is at the Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin, until 5 July 2026.

Click on the pictures below to enlarge