Luigi Ghirri: Polaroid ‘79–‘83, installation view, Centro per l'arte contemporanea Luigi Pecci, Prato, 2 November 2025 – 10 May 2026. Photo: Andrea Rossetti.

Centro Pecci, Prato, Italy

22 November 2025 – 10 May 2026

by TOM DENMAN

Despite being a prolific critic as well as one of Italy’s greatest 20th-century photographers, Luigi Ghirri left no written record of what he intended with his Polaroid project, which he worked on from 1979 until the early 80s. But chances are the medium’s clunky mechanics and ineluctable tactility had more to do with it than the instantaneousness for which it was then celebrated. A Polaroid camera’s fixed-angle lens and the hazy, often fragmentary images it produces – with the print quality depending on ambient temperature as well as light – remind us of photography’s status as a mediator as opposed to a crystalline window. If any of this sounds pertinent now, it may be because a newfound love of analogue aesthetics has precipitated the resurrection of Polaroid after the advent of digital cameras ran the company off the road in the early 2000s.

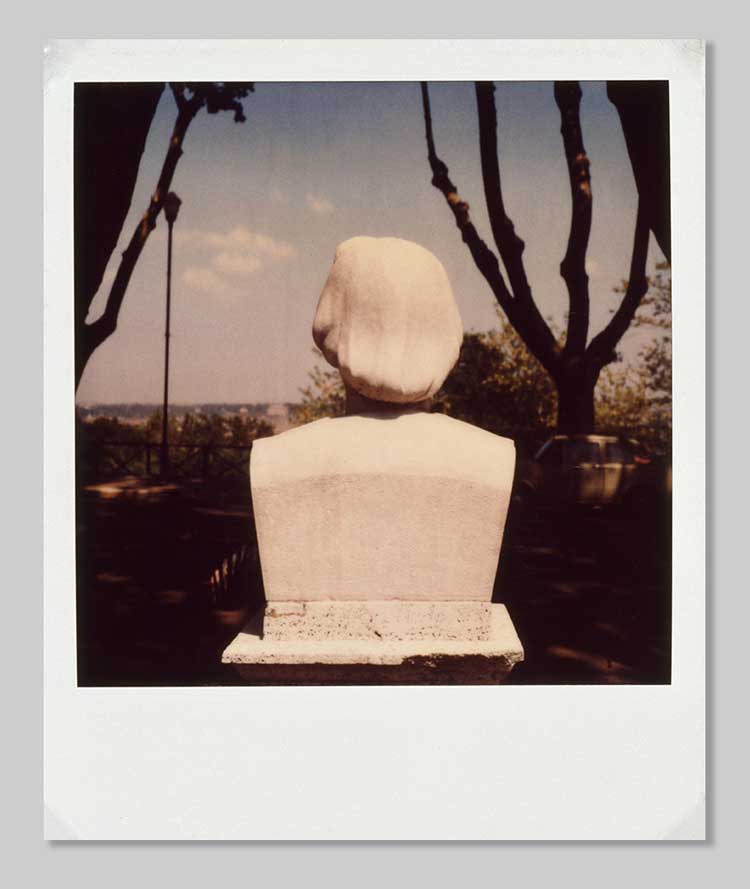

Luigi Ghirri, Roma, 1979, Serie. Polaroid, 8 x 8 cm. © Courtesy Thomas Dane Gallery, London and Naples.

As seen in this exhibition focusing on Ghirri’s work in both the widely used small-format instant camera and the so-called “Giant Polaroid” – which created impressive prints measuring 50cm x 60cm – he was critically attuned to the incompleteness of visual experience. Often this involved framing aspects of the world – especially Italy – deemed to be unphotogenic. Each of his five small Polaroids titled Roma (1979) presents the back of a different marble portrait bust in what appears to be the same Roman park. Unable to identify the men they depict (whether by naming them or projecting on to them some kind of personhood), we are encouraged to consider afresh the weirdness of the appearance of things. We may initially perceive their smoothed-down backs as identical, but their visible hair and headwear is markedly different, as is their position in the park, the latter hinted at – though in a way that is nonetheless fragmentary and unmappable – by a different pattern of tree branches and sky surrounding each bust. We must look rather than label, see diversity rather than project monotony.

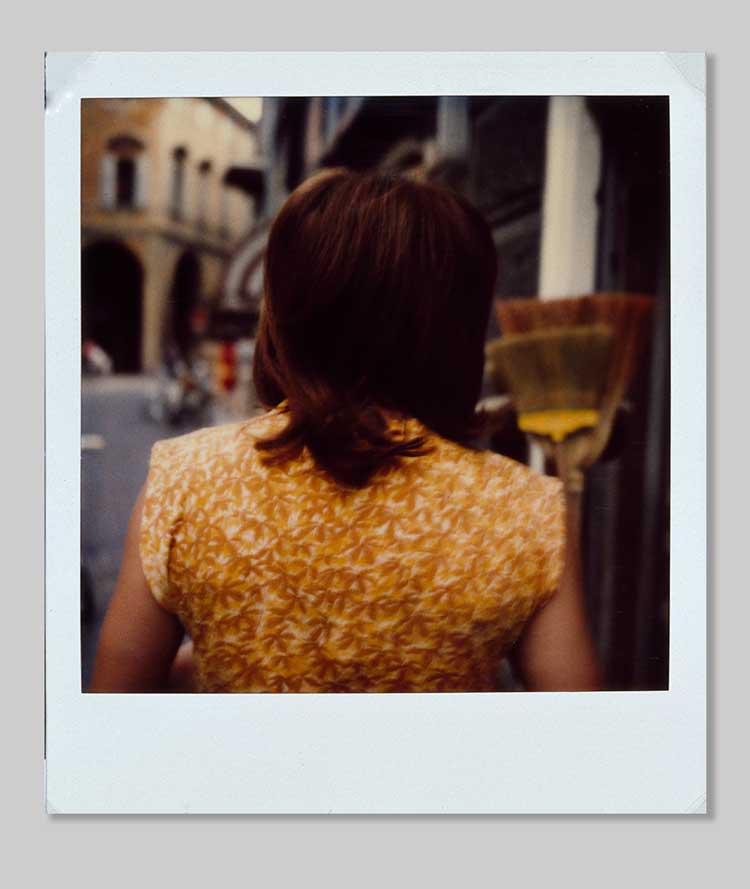

Luigi Ghirri, Modena, 1980, Serie. Polaroid, 8 x 8 cm. © Courtesy Thomas Dane Gallery, London and Naples.

If the square format suggests totality, this only highlights the image’s omissions that render it a fragment, just as the centrality of each bust offsets its wrong-way-roundness. Enhanced by the Polaroid’s dreamy texture, the effect is to keep the image open, and our minds actively envisioning a labyrinthine world – it will come as no surprise that Ghirri was a Borges fan. Visual convention puts us in the “mind” of the statue, but this speculative realm is cordoned off; we go on an imaginary adventure, its infinite pathways metonymised in the expansive vista in the background. A similar thing happens in Modena (1980), where we see the back of a woman’s auburn-haired head and shoulders which block our view of an already blurred Italian street. The woman’s figure is cropped beneath the shoulder blades, and there are two brooms propped against the wall, one of them incidentally the same colour as her yellow leaf-patterned dress. Are these housekeeping implements the real subject of her gaze? The mythic image of Italy – scenic streets, curvaceous women, nice clothes – is distorted. The mismatch between mental image and what we see pushes us to look independently of ideology.

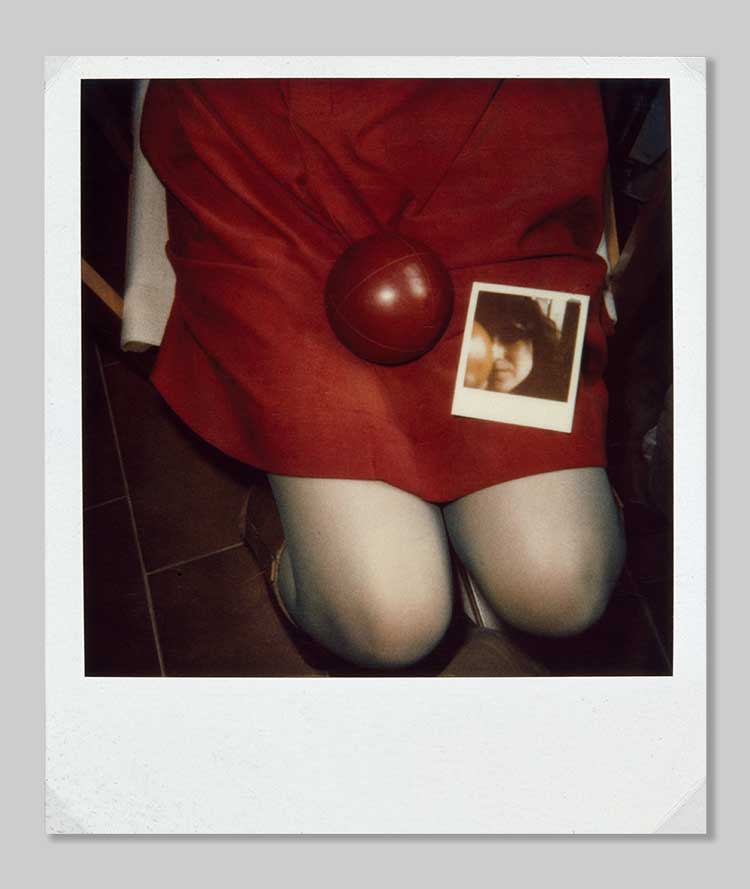

Luigi Ghirri, Formigine (Mo), 1983, Serie. Polaroid, 8 x 8 cm. © Courtesy Heirs of Luigi Ghirri.

The Borgesian conceit of codifying a labyrinth within a tiny space – which in Borges’s case was the short story or fictive essay – resonates especially in Ghirri’s inclusion of leading clues or images within the fragments. Consider Formigine (Mo) (1983): the lap of a woman in a red minidress on which rests a matching red ball, while beside it is another Polaroid depicting possibly the same woman holding possibly the same ball in front of her face, one eye peeking out. The erotic interplay of hide and seek is reminiscent of Velázquez’s Rokeby Venus (1647), whose gaze reflected in a depicted mirror similarly ambushes us. But in Ghirri’s Polaroid the woman is clothed, and the layers of clarity and obscurity multiply at every turn: the unnamed woman could be also looking at the photographer from beyond the frame. And the inserted Polaroid is from another moment, maybe immediately before, maybe earlier (its overexposure suggests it was taken in daylight, whereas the more immediate photograph’s flash-induced chiaroscuro feels nocturnal), and there is no guarantee it is the same woman whose face is still, nonetheless, partially obscured. The synergy of clues is as neat as it is volatile; the enigma of photography is at once reinforced and dismantled, and reinforced in its dismantlement.

Reference to Velázquez is warranted by the way Ghirri frequently turned his camera to much older works of art, often photographs of them in books, slides or other media. He thus nuanced Walter Benjamin’s notion that mechanical reproduction diminished a unique artwork’s aura. He does this pronouncedly in the photographs he made using a Polaroid 20×24 Instant Land Camera, invented in the mid-70s, when the company – wishing to promote its innovation, recognising it was too cumbersome to be a success among the general public – invited some of the world’s leading artists to play with it (Warhol and Rauschenberg were among some of its more famous users). Ghirri would go to Polaroid’s European headquarters in Amsterdam to use this device (which resembled an old studio camera, with wheels, hood and bellows), bringing with him a suitcase of items that he would assemble and shoot. These included dice and toys, for instance – resonating with the playful and contingent nature of Ghirri’s approach – but mostly reproductions of artworks: a creased Piranesi ruin, a self-portrait by Rembrandt in an art book, Antonello da Messina’s Virgin Annunciate (c1476) mosaiced in projector slides. Whereas the wide-bordered smaller images are like peepholes into labyrinthine worlds, Giant Polaroids impose themselves on us, often presenting their subjects at more or less 1:1, if not expanding them somewhat – further positing art’s reproduction as art.

Luigi Ghirri: Polaroid ‘79–‘83, installation view, Centro per l'arte contemporanea Luigi Pecci, Prato, 2 November 2025 – 10 May 2026. Photo: Andrea Rossetti.

In Amsterdam (1980), the art book is opened on a white background, Rembrandt’s face cut out to reveal another, slightly warped and less recognisable self-portrait by the same artist. It is also possible that Ghirri has inserted this picture in the aperture. On the opposite page, Ghirri has placed a projector slide, into which he seems to have put the excised face, as if, in fact, it were printed into the transparency itself. There is a poetic magic to the relationality and trickery of images, animated by the glossy shimmer of the Polaroid, the trompe-l’oeil shadows of pages and slide, and Ghirri’s scrawl along the top of the print recording the details of the exposure. This lends the reproducibility of art an aura in itself, while turning our attention to the mental processes of reception. Rembrandt’s face would be recognisable to many because they have seen reproductions of his work – rather than the painting in Nuremberg, let alone the 17th-century painter in the flesh – and, possibly, other examples of it. Any mental image of Rembrandt is likely a layered hybrid of original and copy, and it is this image that we bring to an original artwork.

In promoting an awareness of the processes that monotonise our experience of the physical world – including art – Ghirri might be trying to restore to Rembrandt’s painting some of its lost aura, something that could be said for Ghirri’s project as a whole. Not that he sees the world as a work of art, but he adopted Polaroid’s inability to disguise its artificiality to get us to keep questioning the mechanisms affecting our perception: we get closer to truth by uncovering the lie of its reproduction. The project is manifestly political because in this way we combat the blind absorption of the myriad images that are fed to us.