Barbican Art Gallery, London

6 October-22 January 2006

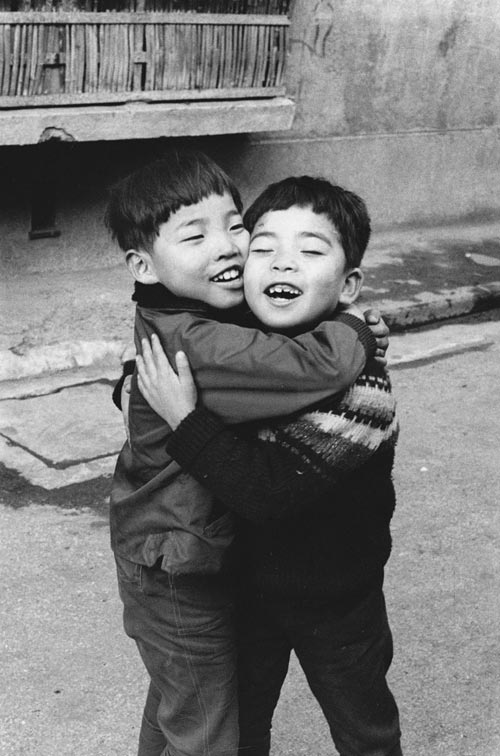

Nobuyoshi Araki. From Satchin and His Brother Mabo, 1963 © Courtesy the artist

Over 4,000 photographs are crowded into both levels of the Barbican gallery. Just to spend a minute studying each would take days, but this exhibition is best appreciated by allowing multiple images to clamour for attention. The way Araki's mind flits from one subject to another makes excellent use of the gallery's almost claustrophobic alcoves and corners. Surrounded on all sides by a jumble of subjects, the viewer sees through Araki's eyes and feels a participant in his compulsion to record everything: snails to flowers, faces to genitals, cats to food. The style also changes from one image to another: composed to spontaneous, black and white to colour, serious to playful.

What especially arouses Araki - as well as the ire of critics - is sex. Araki doesn't seem to go in for the 'serious nude' that even tabloids might forgive (albeit very reluctantly) as art.

In his British shows, most controversy is aroused by the kinbaku (knots with ropes) images in which young women are tied up and suspended from the ceiling of his studio. He says, 'I only tie up a woman's body because I know I cannot tie up her heart. Only her physical parts can be tied up. Tying up a woman becomes an embrace.' Those who call Araki a 'pornographer' or 'misogynist' find this argument unconvincing, but the models seem to be enjoying themselves. According to those who have participated, Araki's shoots are gleeful affairs and his enthusiasm is contagious. There would be far more serious objections if Araki's photographs of pre-pubescent schoolgirls were included but he is (rightly) wary of taking such images on tour outside Japan; even the 'bondage' photographs don't make it to the USA.

By the accepted wisdom of the West, the noted public propriety of the Japanese should be a thin, brittle facade. Under the surface churns a voracious appetite for violent and abusive imagery, and graphic sexuality. The tension should be unbearable; the society should be riven with psychosexual problems - rape, murder, child abuse and domestic violence.

In fact, as the enforcement of censorship has loosened, the rate of sex crimes (already very low in Japan) has fallen. Sober-suited salarymen who read sexually explicit, violent, illustrated novels on the bullet train are far less likely to commit offences against women than their Page Three-reading British counterparts. The Japanese are comfortable with the notion of 'visual language' (perhaps a consequence of the pictographic and decorative nature of their script) and can better engage with visual metaphors than can Western 'literally based' minds. So, what we might consider violent, corrupting pornography, the Japanese can appreciate as harmless fantasy.

Although Japan does not have specific laws against pornography featuring underage children, there are rules against displays of pubic hair - now less strictly enforced in 'art'. A few decades ago, when Araki was threatened with prosecution, he took to scraping away the image over the genitals and substituting daubs of paint (often red, his favourite colour) as a protest against censorship. Some feminist critics mistook this protest for some sort of violent misogynistic urge to mutilate women's bodies.

The idea of applying colour to prints is now an established part of his repertoire. To Araki, a black and white image represents death; it is 'like killing the subject.' He revives the model in his own way, and to his own liking, by adding 'sexual desire and passion' in the form of splashes of colour to the photograph.

This sense of playfulness in his studio work stands in stark contrast to the stern seriousness of other 'transgressive' photographers such as Robert Mapplethorpe, Cindy Sherman and Nan Goldin, and is one reason why Araki is taken less seriously as an artist. Another reason is his prodigious output. Over the last four decades, Araki has published between 250-350 books of photographs (estimates vary).

An attempt at order has been brought to these thousands of photographs by loose thematic groupings - 'self', 'life' and 'death'. The categorisation is an attempt to make the challenge of quantity less formidable, but in the case of Araki, quantity is quality. His interests are as comprehensive as life itself - as full of happiness and frivolity as of gloom and despair. This retrospective also confirms just how little we understand about the Japanese sensibility and how little insight we have into the unintended consequences of our own repressed attitudes to sex.

Rob Johnston