Sheila Hicks, Grand Boules, 2009. Liverpool Biennial 2025 at Tate Liverpool + RIBA North. Photo: Mark McNulty.

Various venues, Liverpool

7 June – 14 September 2025

by DAVID TRIGG

At a time when many old certainties are being eroded and swept away, the theme of this year’s Liverpool Biennial seems especially apposite. Titled “Bedrock”, the exhibition’s 13th edition addresses the things that ground us, whether cultural, social, emotional, or even geological. Although the physical bedrock of Liverpool – the distinctive yellow and red sandstone from which many of its grand civic buildings are built – provided the starting point for curator Marie-Anne McQuay, the theme is largely interpreted in terms of metaphor by the 30 participating artists and collectives, who lead us from contemplations of deep time and the exploitation of natural resources, to the foundational structures of family, community, faith and tradition.

The bedrock of family and kin relations underpin several works in the exhibition, from Sheila Hicks’s Grand Boules (2009) – a series of large, gemstone-like fabric sculptures made by wrapping colourful threads around piles of clothes belonging to the artist’s loved ones – to the poignant multimedia installation Port of Fata Morgana (2024) by ChihChung Chang, in which a model ship created by the artist’s father becomes a vehicle through which intriguing family histories, naval architecture and parallels between the ports of Liverpool and Kaohsiung in Taiwan are explored. Amber Akaunu’s newly commissioned film, Dear Othermother (2025), on show at Bluecoat, questions received notions of family, taking as its starting point the African proverb “It takes a village to raise a child”. Telling the touching story of a matriarchal network in Liverpool’s Toxteth district, it focuses on a group of single mothers who have overcome political, social and financial challenges by building an alternative community through which they collectively raise their children.

.jpg)

Amber Akaunu, Still from Dear Othermother, 2024. Courtesy of the Artist.

In a port city whose foundations are notoriously built on the profits of the transatlantic slave trade, the legacies of empire are a haunting presence in this biennial. The conditions of forced and voluntary migration of African people across history is the subject of Odur Ronald’s installation Muly’Ato Limu (All in One Boat, 2025), also at Bluecoat, in which a cloud of hand-stitched aluminium passports are suspended above metal chairs and jerrycans arranged in the shape of a boat – a reference to the notorious slave ship Brooks, which between 1782 and 1804 made 11 voyages from Liverpool and was immortalised by William Elford’s 1788 engraving revealing the barbarity of transatlantic voyages.

.jpg)

Odur Ronald, Muly'Ato Limu - All in One Boat, 2025. Liverpool Biennial 2025 at Bluecoat. Photo: Mark McNulty.

The installation’s elements conflate past and present injustices, speaking more broadly to global mobility rights. By highlighting the tensions between personal autonomy and restrictions imposed by state borders, Ronald questions the extent to which freedom of movement is a bedrock principle in modern western societies.

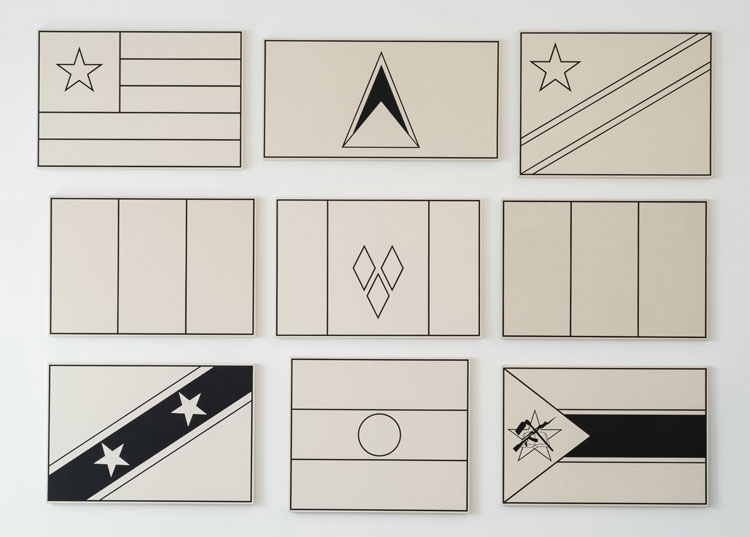

Fred Wilson, GRID OF NINE, 2009. Courtesy of Fred Wilson and Pace Gallery.

Exhibited at RIBA North, Fred Wilson’s painting installation Flag (2009) appropriates the national flags of African and Caribbean countries but drains them of colour, reducing their designs to simple black outlines painted on to unprimed canvases. Commenting on the mutability of postcolonial identities, the work evokes the great losses and erasures suffered by these nations on their journeys to sovereignty.

Hadassa Ngamba, Cerveau 2, 2019. Liverpool Biennial 2025 at Tate Liverpool + RIBA North. Photo: Mark McNulty.

Nearby, Hadassa Ngamba’s painting Cerveau 2 (2019) is an abstract map inspired by the artist’s travels in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Stained with coffee and divided by white lines into 32 units, it alludes to the arbitrary state borders once imposed by colonial powers. On to these, Ngamba has applied pigments made from different minerals and ores, including malachite, copper, cobalt, tar and cassiterite (the last of these, a tin-ore often used in electronics, is frequently sold illicitly to fund violent conflicts in the DRC). With no apparent relationship to any real topography, Ngamba’s map is a kind of psychogeographical meditation on colonial legacies and the environmentally and socially damaging practices involved in contemporary resource extraction in the DRC.

,-2025-Photo-Mark-McNulty..jpg)

Cevdet Erek, Away Terrace (Us and Them), 2025. Liverpool Biennial 2025 at 20 Jordan Street. Photo: Mark McNulty.

Off the beaten track, in a rough and ready warehouse in the city’s creative district, stands Cevdet Erek’s Away Terrace (Us and Them, 2025). Alluding to Liverpool’s love affair with the beautiful game, this large-scale sculptural installation resembles a football stadium, although the dusty arena, which is constructed from compressed earth bricks, suggests a venue for gladiatorial battles as much as Premier League matches. Despite the lack of players or spectators, the noise of a big match is heard and the sound of pounding drums fills the air, alluding to football’s tribal allegiances but also to the wider kinds of divisions and loyalties that exist across society’s political and social spheres.

Imayna Caceres, Underground Flourishings, 2025. Liverpool Biennial 2025 at 20 Jordan Street. Photo: Mark McNulty.

Erek’s bricks are made from clay soil, and several other artists employ raw earth materials, including Imayna Caceres, whose shrine-like installation, Underground Flourishings (2025), comprises more than 100 individual wall-mounted sculptures made with clay from the River Mersey. These diverse forms draw on pre-Columbian motifs and symbols, while on the floor are piles of carefully arranged seeds, leaves and stones. It is an elegant yet frustratingly complex affair, overloaded with esoteric references. According to the wall text, the work “asks us to reflect on the damaging impact of colonial and contemporary exploitation and the extraction of ecosystems which are seen as ‘natural resources’”. This is all well and good, but how Merseyside clay extraction connects with the indigenous cultures of South America is unclear.

Linda Lamignan, We are touched by the trees in a forest of eyes, 2025. Liverpool Biennial 2025 at FACT. Photo: Mark McNulty.

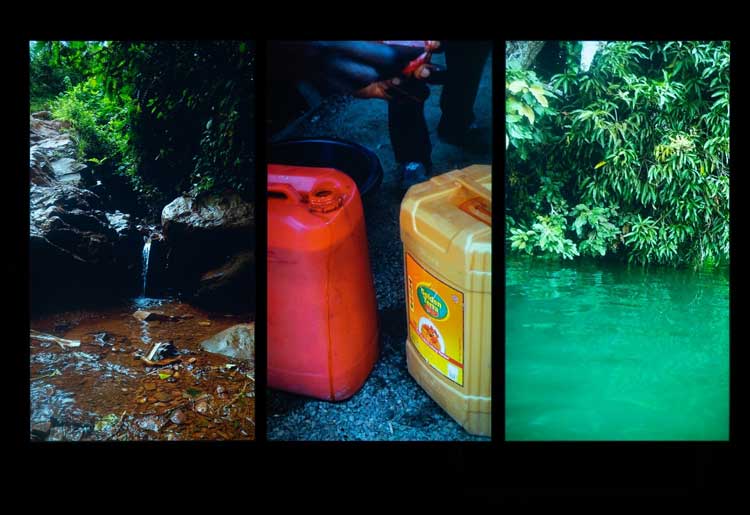

The theme of ecological debasement is addressed more lucidly in Linda Lamignan’s three-channel video, We Are Touched by the Trees in a Forest of Eyes (2025), which centres on Liverpool’s involvement with palm oil and petroleum extraction in Nigeria’s Delta State, an ongoing trade relationship that dates back to the late 18th century. Screened at Fact, the film pits the agendas of multinational oil companies against the animistic beliefs of local Nigerian communities, who are shown performing traditional dances and rituals as they call on nature deities to protect their lands and rivers from violence and oil exploitation.

.jpg)

Elizabeth Price, film still from HERE WE ARE, 2025. Courtesy of the artist.

Faith is a significant bedrock for many in Liverpool and the city boasts two extraordinary cathedrals (its Catholic cathedral, locally nicknamed “Paddy’s Wigwam” because of its unusual modernist design, was last month awarded Grade I-listed status). In one of the biennial’s standout works, Turner Prize-winning artist Elizabeth Price examines the radical character of modernist Catholic churches, which were built across the UK in the postwar years, largely for immigrants from Ireland but also those from southern and eastern Europe. Screened at the Black-E, a community centre in Chinatown, Here We Are (2025) is a captivating and stylish video essay about the Catholic diaspora in Britain and the architecture it advanced. Beginning with the remarkable 1937 futurist church Our Lady Star of the Sea and St Winefride in Amlwch, Anglesey, it features a string of bold and daring designs which are accompanied by a collage of voices that invite consideration of how these buildings reflect notions of belonging and difference.

.jpg)

Maria Loizidou, Where Am I Now?, 2025. Liverpool Biennial 2025 at Liverpool Cathedral. Photo: Mark McNulty.

At Liverpool’s Anglican cathedral, Maria Loizidou’s spectacular large-scale textile installation Where Am I Now? (2025) hangs prominently from the Dulverton Bridge. Hand-woven from thin steel threads, it depicts different species of migratory birds that have been spotted around the grounds of the cathedral. Unrestricted by geopolitical borders, these winged creatures symbolise migratory freedom but, towards the top of the tapestry, we see them carrying people, as if transporting them to heaven – a striking image of redemption that resonates with the ecclesiastical surroundings.

Kara Chin, Mapping the Wasteland: PAY AND DISPLAY, 2025. Liverpool Biennial 2025 at FACT. Photo: Stuart Whipps.

At Fact, birds of an altogether different kind feature in Kara Chin’s zany installation Mapping the Wasteland: Pay and Display (2025), in which Liverpool’s scavenging seagulls become animated ninjas, attempting to snatch food in a room of flashing lights, brutalist architectural models, weeds, a pay and display machine and piles of guano. As a lighthearted response to the nuisances of modern city life, it injects a welcome moment of levity to the biennial, although (as with several other works) it feels tangential to the core theme.

Although there are fewer participating artists than in some previous years, the biennial still feels unwieldy to navigate; indeed, you would be hard pressed to see everything in a day. But that seems appropriate given that this edition has ostensibly been conceived primarily with the people of Liverpool in mind: those who make the city their home. McQuay has herself lived here for a decade and this is very much reflected by her thoughtful curatorial approach, which prioritises a sensitive engagement with the city’s layered histories and complex sociocultural fabric. This biennial asks us to consider where our foundations lie and what kind of future might be constructed on them. As suggested by its strongest works, those foundations must be rock solid, otherwise we risk building on shifting sands.