Jeremy Deller. Meet the Gods, Dundee, 2025. Still from Otto Cox, courtesy of Jeremy Deller.

by VERONICA SIMPSON

Ten minutes into my interview with Jeremy Deller, he tells me he is not interested in reading what I write about him. No offence is intended, and none taken. From Deller this statement is entirely in keeping. Rarely have I met an artist less interested in his own profile or having his ego massaged – or less keen to analyse his work. To place his comment in its conversational context, he says: “I try not to be too self-conscious. You’ll do this interview, but I won’t read it. I won’t look at myself on film or listen to myself if I do an interview. I don’t want to read a review.”

This lack of self-consciousness is probably an essential ingredient in someone who works so consistently with the public. An ability to put your ego to one side is vital if you want to liberate whichever aspect of popular culture has inspired your ideas. In his 2023 book Art is Magic, which is as entertaining an artist’s biography as you are ever likely to read, he says: “The public are more or less up for doing things, sometimes just out of curiosity, which is what makes the world go round for an artist like myself.”

Having studied art history at the Courtauld and then Sussex University, he discovered his calling as an artist several years later, when he realised he didn’t have to make anything with his hands but could activate people with his oddball ideas. Or, as he says in his book, by bringing “two elements together and then stand[ing] back to see what transpires”. Acid Brass (1997) was the breakthrough work, fusing the nostalgic warmth and camaraderie of a brass band with the driving, rhythmic energy of acid house music. He picks his collaborators well. For this, he approached one of the UK’s best brass bands, the Williams Fairey brass band, and persuaded them to give it a try, debuting the experiment at The Bluecoat arts centre in Liverpool. It turned into one of his most popular and enduring performance works – even chosen for the opening party of Tate Modern in 2000.

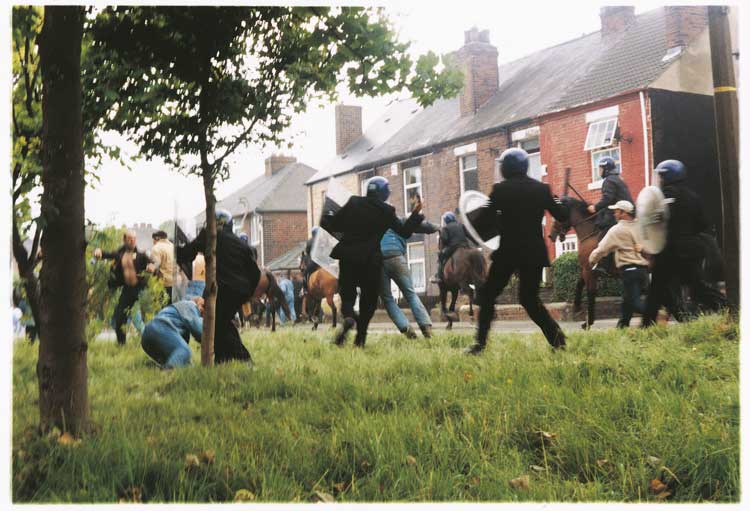

In 2001, he made The Battle of Orgreave, recreating the historic 1984 clash in Yorkshire between the police and striking miners, using former miners and historic re-enactment enthusiasts. The resulting film, directed by Mike Figgis (another stellar collaborator), has been described as having “changed the course of contemporary art”. In 2009, Deller drove across the US, from New York to Los Angeles, towing a car destroyed in a Baghdad bomb attack two years earlier, accompanied by a US war veteran and an Iraqi citizen (It is What It Is).

Jeremy Deller. It Is What It Is, 2009. The car in front of a mural depicting the fall of Baghdad near 29 Palms, California. Courtesy of The Artist and The Modern Institute / Toby Webster Ltd., Glasgow.

He won the Turner Prize in 2004 for Memory Bucket (2003), a documentary about Texas. Subsequent documentaries include Everybody in the Place: An Incomplete History of Britain 1984-92 (2018), which translated into film a mind map he first sketched out in 1996, called The History of the World, which charts the evolution of 20th-century Britain through music.

Jeremy Deller. Everybody in the Place: An Incomplete History of Britain 1984-1992, 2018 (film still). HD Video Courtesy of The Artist and The Modern Institute / Toby Webster Ltd., Glasgow.

Sometimes he has fun blowing up sacred cows, such as the reverent, pickled-in-aspic preservation tendencies of the heritage industry. Sacrilege (2012) apparently emerged from daydreams about “what the stupidest idea it was possible to make would be, the sort of thing you might see on The Simpsons”. And thus, a full-scale bouncy castle-style inflatable replica of Stonehenge was born.

In 2013, he represented Britain at the Venice Biennale with his pavilion titled English Magic, looking at different kinds of magic – in particular the sleight of hand by which politicians or the super-rich get away with presenting something bad as good, or vice versa.

Deller has also demonstrated a deftness with memorial events: poignant and yet completely unsentimental, We’re Here Because We’re Here (2016) commemorated the first day of the Battle of the Somme, 1 July 1916, when more than 19,000 British soldiers were killed. Deller, with the help of various regional theatres and advice from the National Theatre’s then director Rufus Norris, recruited more than 1,000 young men to dress as soldiers, each carrying a card with the name and regiment of a dead soldier and the words “Died at the Somme on 1st July 1916” and the hashtag #wearehere. They materialised, with no fanfare or pre-publicity, at railway stations and shopping centres all over the UK, silently handing out their cards if people spoke to them, and at the end of that day, 1 July 2016, they disappeared.

Jeremy Deller. The Triumph of Music, Derry, Northern Ireland, April 2024. Photo courtesy Jeremy Deller.

Deller has spent the last two years working with the National Gallery to develop a programme of celebratory public events to commemorate its 200th anniversary. With the overall theme The Triumph of Art, The Triumph of Music kicked off in Derry, Northern Ireland, in April 2024, with a celebration of the local music scene, but specifically the bands and venues that prevailed in the 1990s, despite the ongoing sectarian and political violence of the Troubles, articulating in the process something of what it took to keep enjoying music against such a backdrop, as well as what music did to maintain the community’s resilience. In May this year, Meet the Gods took place in Dundee, with a pageant inspired by scenes from the National Gallery’s painting by Titian, Bacchus and Ariadne, with costumes made by students from Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and Design, which also drew on a traditional student/street parade called The Revels, which occurs at this time.

.jpg)

Jeremy Deller. Meet the Gods, Dundee, 2025. Instagram, poster. Still from Otto Cox, courtesy of Jeremy Deller.

In June, for the summer solstice, Deller was in Llandudno for Carreg Ateb: Vision or Dream? It entailed a street party and celebratory rituals including a performance by young actors from Bangor’s Frân Wen company, who developed their own mythological characters for the event. They also made a film – set in the Manod slate quarry in which the National Gallery’s collection was stored, during the second world war – currently showing upstairs in Mostyn art gallery, Llandudno. Over that weekend, members of Frân Wen and the wider community convened at the Neolithic site Bryn Celli Ddu in Anglesey.

Jeremy Deller. Carreg Ateb: Vision or Dream?, Llandudno, Wales, June 2025. Photo: Mark McNulty.

The solstice weekend also saw a show opening at Mostyn with new, commissioned works from five early career Welsh artists, shown alongside works by Deller and objects from the National Museum of Wales, Llandudno Museum and Storiel. The featured artists were: Esyllt Angharad Lewis, with a multimedia installation; Gweni Llwyd, whose moving image work explored quarries as spaces of possibility, creativity and connection rather than relics of labour and loss; Lewis Prosser, with exquisite ceremonial wicker sculptures; Llyr Evans, with a three three-channel video; and Sadia Pineda Hameed, whose tactile installation invites us to cross borders in our imagination, while negotiating different forms of identity. Of his own works, Deller has chosen to show So Many Ways to Hurt You: The Life and Times of Adrian Street (2010), the fascinating documentary he made about the Welsh miner turned exotic wrestler, with the screen framed by a new mural by Heidi Plant (Deller commissions a new mural to surround the screen each time he exhibits this work), and The Uses of Literacy (1997), his “fan art” collection in tribute to the Welsh rock band Manic Street Preachers. The show also features a newly commissioned site-specific banner by Deller’s long-term collaborator Ed Hall.

Deller spoke with Studio International in person, at Mostyn gallery, Llandudno.

Veronica Simpson: With all the work that you have had on in the last year – on top of this massive National Gallery 200th anniversary party - it must feel as if you are coming towards the end of an art marathon.

Jeremy Deller: Well, there’s the Trafalgar Square celebration at the end of July. So, there’s six weeks left. But, yes, it’s been two years in preparation and even before that it’s been years of thinking.

VS: When did the National Gallery approach you?

JD: It was 2017. Then not much happened until two or three years ago.

VS: What was the original brief?

JD: They asked if I would do an event to celebrate its 200th anniversary, a public event. We came up with this idea of a big party and processions.

VS: So, it had to be nationwide, involving the public.

JD: Yeah. In the open, public realm. Free to go to. All those things.

Jeremy Deller. The Triumph of Music, Derry, Northern Ireland, April 2024. Photo courtesy Jeremy Deller.

VS: It’s such an interesting selection of places – hats off to you and the National Gallery for picking them. Plymouth, Dundee, Llandudno, Derry.

JD: They’re not the capitals of the nations like London is. We’re not going to Glasgow or Edinburgh. Sometimes you want somewhere that’s not quite so big to work in.

VS: Indeed, but all these cities have amazing culture, great artistic institutions, a sense of their own heritage and strong creative communities that not everyone knows about. I think the locations are very well chosen.

JD: Thank you. I mean, I had a hand in some of it – here, for example. Also, they are all very difficult places to get to from London. Which played a part.

Jeremy Deller. Carreg Ateb: Vision or Dream?, Llandudno, Wales, June 2025. Photo: Mark McNulty.

VS: I was reading an interview with a fascinating artist in her 70s, Kiki Smith, in Studio International, who said artists are always trying to reveal themselves and remain hidden at the same time.

JD: That’s very good. Some artists … all they do is just reveal themselves and go on about themselves. But a lot of artists are hiding and showing.

VS: Is that you? I mean, one of the distinctive things about your art is it’s not about you.

JD: No. And I’m not in it. I don’t appear in it.

VS: Smith also references the importance of the space between yourself as an artist, your impulses and the work you are making. What is interesting, she says, is that space between these things. Do you agree? Do you have a sense of that space?

JD: What, were I am in the work? No, not really. All the things I work with are the things I’m interested in. People: I’m interested in what they do, the themes and subjects.

VS: But you have an instinct about what needs to be voiced or what’s interesting or missing in public discourse?

JD: Yes, I suppose you do have an instinct. You just go with your own interests, and you don’t think: “Oh, people are talking about this, I must look at that.”

VS: Though often you go against what is mainstream, you look for the off grid and the underrepresented.

JD: Sometimes. But on the whole, it’s just what interests me. And you assume that if it interests you, then there’s going to be someone else interested. It can’t just be you.

VS: It is fascinating though that things you picked that were seen as deeply unfashionable or uncool at the time – folk artefacts, magic or morris dancing – have now crept back into fashion.

JD: Yeah. But I’m not looking for the next thing. I’m just following my nose and seeing where it takes me. You want to be surprised by what happens. You want to have a career in which you’re not even clear in two years’ time what you’ll be doing … just because some opportunity arises. That’s the big thing about making work with the public. You offer something up and then it’s takes on its own direction and life.

VS: When you plan a participatory project, there’s no sense of you trying to control what happens, the outcomes, or the impacts? You must have some objectives?

JD: Not really. You plan and you make sure that what’s going to happen is what you want, but in the environment, in the open air, with the weather, you can’t control what happens, it’s impossible. For me, you just experiment really and put something out. Then stand back and see what happens.

VS: I was interested to learn that you studied art history at university, so you weren’t planning on being an artist early on. The young Jeremy Deller didn’t think that was an option.

JD: It wasn’t available. There was no career path. It wasn’t going to happen. It was like thinking about becoming a scientist having not studied science. It was nothing to do with my art history studies, that was just something I was studying to be close to art. That was the next best thing. It was a gradual, slow-motion thing, over a period of years. I was unemployed, took photographs, did bits and bobs, got into a printmaking class for unemployed people and carried on from there. There was a seven-year penny-dropping experience.

VS: You put that show on in your bedroom, [Open Bedroom (1993)].

JD: It wasn’t in the bedroom, it was in the house. It was meant to be in the bedroom, but it took over.

VS: What was in it?

JD: Some paintings I made – the first and last paintings I ever made – some photographs, some bits of text from the men’s toilets in the British Library, some T-shirts I’d made.

VS: And the T-shirts have continued.

JD: So has publishing and playing around with culture basically.

VS: You were interested in 1990s rave culture, and that sense of rebellion and hedonism and protest. The rave scene did seem like an act of protest, at a time when there was a lot of complacency, and consumerism and corporate ambition were flying high.

JD: There was a lot going on. But in 1994 there were protests about dance music. I was very happy to experience that scene.

Jeremy Deller. The Battle of Orgreave, 2001. Police officers pursuing miners through the village. Courtesy of The Artist and The Modern Institute / Toby Webster Ltd., Glasgow. Photo: Parisah Taghizadeh.

VS: When did you feel moved to coalesce that interest in protest and popular culture into an artwork, for example The Battle of Orgreave (2001)? That was a kind of protest.

JD: In a sense, but it was about a historical moment. That was something I was very interested in, having seen the 1984 miners’ strike on telly, the scenes were still with me. I was just lucky to get an opportunity.

VS: It was an amazing project to land as such a young artist – the Artangel commission pretty much funded two years of research, and you really did your homework.

JD: Yeah, it took over. As it should. Like this (the National Gallery event). It was a very big opportunity. I spent a lot of time travelling around Britain talking to people. I didn’t document it at all. It was mainly former miners, those were the people I was interested in, I wanted to get their version of events. The re-enactors weren’t there. They came later. They hadn’t been present. And they were scared of the miners, who brought a degree of realism they’d never been subject to. In a re-enactment, you don’t get that. There’s nothing at stake with a re-enactment, because it’s ancient history (except maybe the civil war ones). But really, it’s just acting, effectively. When you’re up against people who were part of a campaign or in the original battle, you pick up on that and it really intimidated them, as did the camaraderie of the former miners. The re-enactors had never seen that element before – men like that being together and being a unit and being mates. I think that really intimidated them, that esprit de corps.

VS: I can see these are fascinating elements to work with.

JD: Yeah, big male energies.

VS: And Adrian Street had lots of that. I so enjoyed watching your film about him in the exhibition.

JD: That was nine years after. Yes, he had big male energy as well.

VS: But it seems he was a little guy – he compares himself to Alexander the Great in the film, who was apparently only five feet tall, but used props and costume elements to make himself appear bigger, as Street did. How tall was he?

JD: He was my height or shorter. His dad was tiny as well. Welsh miners, maybe they were shorter because of diet and lifestyle or almost evolutionary reasons – it’s better to be small when you’re spending time in a mine. But he made up for it in his personality and toughness. He was a very single-minded and determined person.

Adrian Street with his father at the pithead of Bryn Mawr colliery, Wales, 1973. Photo: Dennis Hutchinson.

VS: I’m interested in the threads spun by the experience of making one work, and how that connects to the next. Your interests are so broad. What connects, say, the Battle of Orgreave, which was probably a seminal work, to the ones that followed.

JD: Well, I don’t think about it. In a way, that’s for other people to think about, make sense of. I try not to be too self-conscious. You’ll do this interview, but I won’t read it. I won’t look at myself on film or listen to myself if I do an interview. I don’t want to read a review.

VS: But that’s also a conscious decision, a discipline, isn’t it?

JD: Yeah. You can’t read your press or, if you do, you have to read it all, good and bad. Some people would obsess over what’s written about them – feel aggrieved, or whatever. And I don’t want to think about things too much, I just want to keep doing rather than thinking.

VS: The National Gallery Project – The Triumph of Art –could be seen as a kind of protest against austerity and the slashing of arts budgets and arts education in UK schools. It’s giving lots of ordinary people an opportunity to make music, make art, create spectacle, have fun. That seems to be a public demonstration of sorts.

JD: Of sorts.

VS: Does that link to the thread of shining a spotlight on things that might be considered unfashionable?

JD: It’s not even that. It’s just things … like a lot of relatively random things you can look at and walk around - an easy-going event because there’s music, there’s fun, it’s not very staged.

VS: But it’s very inclusive.

JD: I suppose it is inclusive. It’s not like massively professional in the traditional sense. It’s not corporate. It’s something else.

VS: By staging these processions, are you tapping into a nostalgia for rituals that used to happen all the time in communities and villages?

JD: They still are. Nothing’s really gone. If anything, because of the internet, it makes these things massive – these big dangerous ones. Like cheese rolling and all these big football matches between towns, which are now more popular than they’ve ever been. It’s like they go on a bucket list of things to do, like running with the bulls of Pamplona. In terms of film, it’s incredibly attractive to people. If anything, I think they’re more popular now than they’ve ever been.

VS: You’ve had a really busy year, what with this and the Bradford City of Culture event.

JD: Yeah, it was good that. Yeah, May was very busy. I also had a commission in Scarborough with a mosaic. And an exhibition in Hannover that I curated for the Kunstverein.

VS: How do you manage it when there is so much going on at once?

JD: By chance, it all came together in May. I was barely at home. And I’ve barely been at home in June either. But you should be glad you have these moments, basically. Not everyone gets the opportunity to be as busy as I am. I’m not complaining.

VS: Is that busyness abating or is 2026 looking just as busy?

JD: No, 2026 won’t be like this. It’s a little quieter, then it will get busy. It’s busy enough.

VS: What’s the most personal work you have done, or one that you felt most personally invested in?

JD: Are we talking about a favourite work? The work that I thought was probably my best work was when I took the car that had been destroyed in the Iraq war around America. And I think that was the best thing for me personally, it was full of so much potential, and danger, but very interesting.

Jeremy Deller. It Is What It Is, 2009. Photographs taken throughout the tour, Houston, Texas. Courtesy of The Artist and The Modern Institute / Toby Webster Ltd., Glasgow.

VS: You were putting yourself at personal risk in terms of the reactions you might have provoked?

JD: It was a kind of crazy thing to do but I love the fact that I could do it. I think if you did that now, America is a very different place, so it would be hard to make a work that was that potentially confrontational without getting into trouble.

VS: Have you got anything brewing that you feel as excited about?

JD: If I did, I wouldn’t tell you. There will be things happening next year, I’m sure. I’m not worried. But hopefully less intensive travel. I’ve barely been abroad to work because I’ve been so busy here.

VS: Something like this generates a lot of discourse, a lot of sharing, shared experiences for the people involved. It must feel like an incredibly valuable thing to be putting out there now.

JD: Yeah. I suppose so. I don’t think about it. I don’t feel I should be responsible for that. That’s just a byproduct, but that’s good that it happens. I’m not thinking: “Am I a good person to do this?” I just do it. It’s just one of the benefits. Of course, when you work with people, it’s good that they’re having all these experiences.

VS: Which community do you feel you have had the most interesting interaction with, through any of your works?

JD: I’ve had a very nice relationship with a steel band. I like being with musicians or groups of musicians. And they’re playing in Trafalgar Square, so that’s nice – playing twice. I work with so many people I’d have to look at my book. There are some gardeners in Munster I’ve enjoyed working with.

VS: There’s an amazing group of youngsters from a theatre company in Bangor who are performing tomorrow. I saw the film upstairs of them dancing in the slate quarry.

JD: Yeah. They’re performing on the promenade tomorrow, which will be great. I’m really looking forward to that.

VS: I can imagine that might be a seminal moment for them – talking to an artist such as yourself, doing what you do. It could be a light-bulb moment: that you can do what you do for a living.

JD: Maybe.

VS: I mean, if such an event had occurred for you at 16, you might have followed this pathway sooner?

JD: Yeah, it’s possible. Again, I don’t think about it too much. They’re in a theatre group, they’re always up to something interesting. That’s why they do it. I’m just another person that they meet, like dancers or choreographers come along. I’m just one of many, I suspect. They’re performing near the Neolithic burial chamber. Tonight - well tomorrow. It’s one of the famous chambers where, as the sun rises the light goes right the way through it because of the alignment of the sun.

VS: Have you visited other Neolithic sites? I visited the stones at Callanish on the Isle of Lewis last year, which felt quite special.

JD: Yeah. I’ve been to Callanish. I’ve been to a lot of them. I haven’t been to enough of them. I was on Dartmoor last week with some people, on a project.

VS: Do you visit these ancient sites for your own personal interest as well as work?

JD: Sort of. Not for any spiritual reasons. I’m not like a hippy in that respect. I’m interested when people believe certain things, but I don’t necessarily believe. I’m not a sceptic. I’m just someone looking in, really. And sort of interested in it.

VS: There’s no danger of any of this stuff getting any less interesting to you?

JD: No. I might take a break from it. But not next year, I’m not taking a break from it. I’m doing something else.

VS: What would a break look like for you?

JD: Er … a tree. Sitting under a tree. That’s what I want. Reading a book. That’s literally all I want. I’d love to do that for a month.

• Carreg Ateb: Vision or Dream?, part of the National Gallery’s The Triumph of Art is at Mostyn Gallery until 27 September 2025. The National Gallery celebrations travel to the Plymouth Hoe for an event titled Hello Sailor on 5 July. There will be a procession from the Box art gallery to the Tinside Lido, including key creative institutions from the region. The NG200 celebrations will conclude with a family friendly event – with many of the previous participants convening – in Trafalgar Square on 26 July.