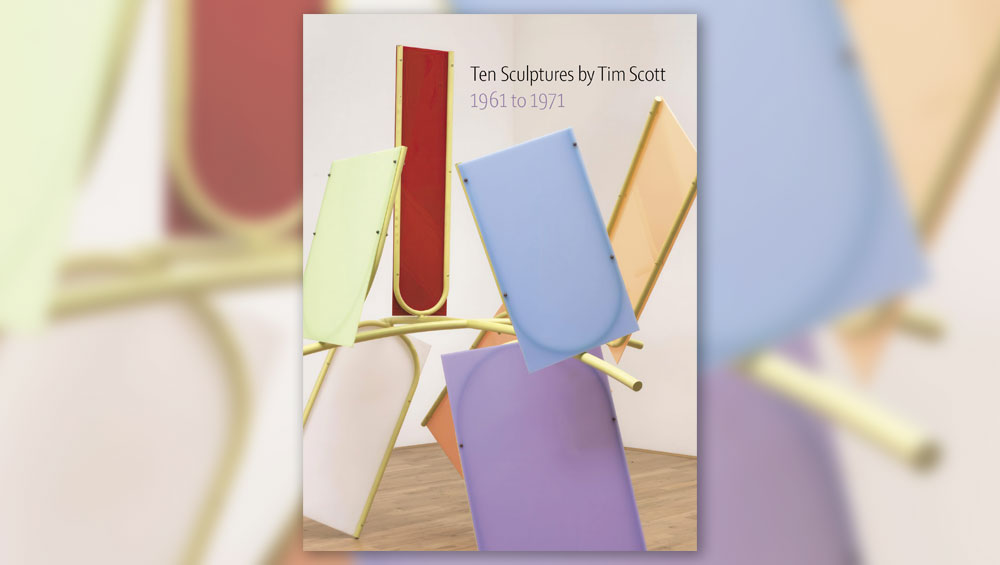

Ten Sculptures by Tim Scott 1961-71 by Sam Cornish, published by Sansom & Co.

reviewed by ANNA McNAY

Tim Scott (b1937, London) is known for his abstract sculptures made from transparent acrylic and steel. He was the first of the group of sculptors who later became known as the “New Generation”. In this 80-page, full-colour monograph, writer and curator Sam Cornish focuses on 10 works made by Scott between 1961 and 1971 and brings to life and exemplifies what he describes in his eight-page introductory essay as the “precisely structured … joy of hedonism” inherent in Scott’s work. Although primarily discussing these 10 works, Cornish brings many more pieces to the conversation, most of which are also illustrated with good, clear images. Scott complained in his notebooks that, at the New Generation exhibition at the Whitechapel Art Gallery in 1965: “No one, to my knowledge, has actually gone round that show and criticised the SCULPTURE ITSELF in an objective and constructive way.” He cannot grumble at Cornish, who here looks at each individual sculpture in an intimate and critical manner. While Scott’s work might appear theoretical and academic, and it was indeed rooted in intense discussions about the nature of sculpture, it can also be understood more simply, and it is possible to take as much or as little from this book as you wish – it is written in depth, but clearly and in an accessible style.

While studying at the Architectural Association, where he understood architecture primarily “plastically”, as a matter of forms in space, Scott also studied sculpture part-time by taking day classes at Saint Martin’s School of Art with Anthony Caro. Caro encouraged his students to make sculptures of impossible things: the street, a scream or a shout, for example. In turn, Scott held a belief in sculpture as a fundamental part of human experience. Cornish quotes him as saying: “Sculpture acts by displacement; it is the state of being, the state of feeling, the state of experience, the state of physical awareness and sensation, the state of confrontation by physical phenomena; not these things themselves or an interpretation of them.”

_extended.jpg)

Tim Scott, Peach Wheels, 1961–62. Wood, glass, paint, 122 × 137.5 × 91.5 cm. Photo: © Tate

Cornish’s introductory essay presents Scott’s trajectory, introducing the artists from whom he drew inspiration. These include Eduardo Paolozzi, who was a visiting tutor at St Martin’s; Le Corbusier, in whose Paris offices he worked after graduating; Henri Matisse, whose cut-outs had a profound effect on him (and the painter Alan Gouk is quoted as saying Scott’s sculpture “inhabits the same world”); Mark Rothko and his colour-field paintings; and David Smith, who inspired Scott to begin using materials such as fibreglass, glass, metal and acrylic sheets. Highlighting the importance of the decade covered by Cornish, a foreword by William Tucker describes Scott’s work of the later 1960s as “more open and playful, more ambitious and more personal” and his work of the 1970s as “undergo[ing] a contraction, to become dense and compressed”. Cornish also notes a “break” at this point. But we shall return to this later on.

Further to his “structured hedonism”, Cornish lists a bunch of oppositions present in Scott’s work: open, closed; full, empty; plane, volume; lightness, weight; precision, excess; monumentality, immediacy; groundedness, levitation; sculpture, architecture; sculpture, painting. The first work to be looked at (they are arranged chronologically) is Peach Wheels (1961-62), which Cornish describes as “stat[ing] paradox with the concision of a well-delivered punchline”, concluding with the former keeper of the Tate Gallery Anne Seymour’s description of it as epitomising Scott’s work’s “unreal reality”. The work could almost be understood figuratively, and yet, and yet …

Tim Scott, Dulcimer, 1961–64/65. Wood, fibreglass and glass, 91.5 × 305 × 91.5 cm. Photo: © Tate

Second, we encounter Dulcimer (1961-64/65) (the date range is so great because the maquette wasn’t made into a full-size sculpture until Scott was given a stipend by the gallerist Leslie Waddington in 1964). “If Peach Wheels is a one-liner,” Cornish writes, “Dulcimer is a more complex phrase”, a series of successive open and closed forms in the manner of Picasso’s cardboard construction Guitar (1912). More directly, the work shows the influence of Constantin Brâncuși and exemplifies what Cornish terms Scott’s “horizontal Brâncuși-ism” – namely taking the shapes and forms of the Romanian sculptor but spreading them on their sides. (Cornish also notes that the reclining forms of Henry Moore must have been an influence, too.) In talking about Scott’s work, one should perhaps use the term “shape” rather than “form”, because his works are opened out with the components not necessarily connecting. (“The problem of sculpture is the problem of SHAPE and it is through shape that impact must result,” Scott wrote in his notebook.) Nonetheless, mass must be valued as inherent to sculpture, and the paradox of Scott’s desire for open sculpture to retain a sense of “a kernel, a nucleus, a core” (a central mass) is his central one, made especially clear in the discussion of Quantic of Sakkara (1965), an opened-out stairway, partially dressed with fibreglass shapes, and standing on (or right next to) flat, coloured sheets.

Tim Scott, Quantic of Sakkara, 1965. Wood, fibreglass, steel, re-made in aluminium, 205 × 455 × 275 cm. Photo: Anthony Caro Centre.

As is also the case with Curlicue I (1963) and Quadreme (1966), these sheets of Perspex function as what could be called “pseudo-plinths, memories of plinths that have been incorporated completely into the sculpture”. They mark off the sculptures from “real space”, yet simultaneously claim the whole expanse of the gallery, and invite the viewer to measure the artwork against their own body. Curlicue I holds a tension, as its core is made of latex foam that would return to its flat form if removed from its Perspex container – an unspoken promise (or threat) of geometric tautness transposing into “fluid motion”. The solidity of Quadreme is similarly “enlivened with intimations of speed, generated by its zig-zagging central motif, and by its slight deviations from basic geometric divisions” (again, suggesting the idea of shape over form).

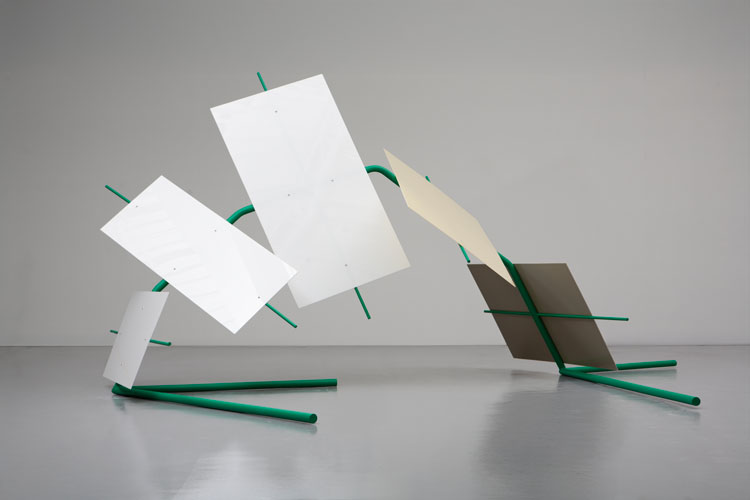

Tim Scott, Bird in Arras III, 1968.

Acrylic sheet, steel, paint, 282 × 579 × 416 cm. Photo: Cylla von Tiedemann.

Quinquereme (1966), Cornish proposes, might be seen as the culmination of this first phase of Scott’s sculpture and his engagement with Brâncuși, and it is the last work in which he stages a clear opposition between closed and open volumes, “open, at times expansive, but still autonomous and self-contained”. After this, comes the Bird in Arras series, from which Bird in Arras III (1968) introduces an active structure, with the meeting of the rectilinear and the curvilinear in the arc of its spine, feathered with plain Perspex sheets.

Tim Scott, Bird in Arras VI, 1969. Acrylic sheet, steel, paint, 270 × 291.5 × 218 cm. Photo: Tim Scott Archive.

Bird in Arras VI (1969) exemplifies the colour Scott took from the cut-outs of Matisse and the painting of colour-fields by the likes of Rothko. Its seven acrylic sheets are at once colour and material, and this is the “most richly and successfully polychromatic of Scott’s sculptures”, bringing with it “the potential for immediacy, speed and flexibility”.

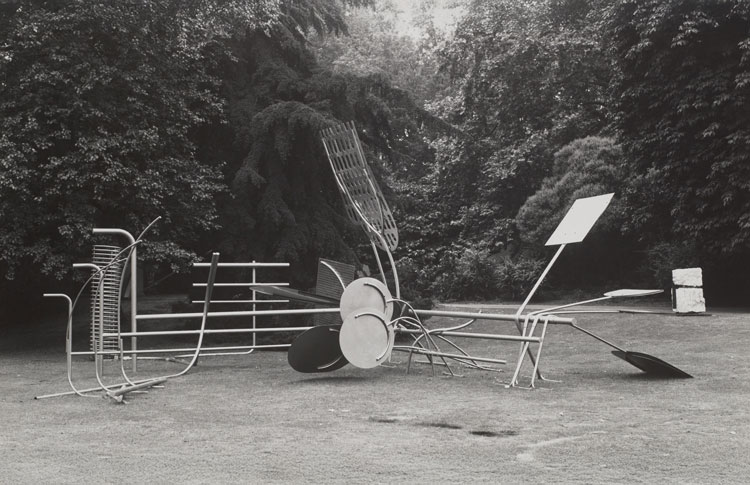

The final work to be discussed, Cathedral (1970-71), really makes clear the change in direction of Scott’s work. His largest sculpture by far, at more than 5 metres high, 15 metres long and 9 metres wide, it was inspired by the ruined abbeys of Fountains and Rievaulx in North Yorkshire, and it was his first sculpture both to be made entirely in steel and to be shown outside. Scott has often been defensive about comparisons between his sculpture and architecture, but Cathedral moves beyond this distinction, requiring the viewer to enter its sphere. “If his work of the 1960s had evoked a narrative of creation of the mind rather than the body,” Cornish says, “from Cathedral on, creation was increasingly a physical act.” But as Scott adds: “There are no real solids – there are very large bits of material, but they don’t make up a big solid mass. They are all transparent.” And, he says: “Cathedral becomes most fully itself when viewed from close-up.” Again, there are echoes of Rothko’s instruction that his paintings should ideally be viewed from a distance of 18 inches. Can Scott’s works be understood as “sculptural equivalents to the clarified mirage-like images of colour-field paintings or post-painterly abstraction”?

Tim Scott, Cathedral, 1970–71, in A Silver Jubilee Exhibition of

Contemporary British Sculpture, Battersea Park, London, 1977. Steel, c450 × 1520 × 912 cm. Photo: Conway Library.

The book ends with extracts from Scott’s personal notebooks (1958-65) and extracts of his reflections on sculpture (1967) and colour in sculpture (1969). After all, who can say it better than the artist himself?

This book provides a thorough introduction to and overview of a fascinating artist who has been far too overlooked in his own country (while being better known in Germany). Surprisingly, the Tate collection holds 12 sculptures by Scott dated 1961-71, but these are rarely shown. “Encountering one of Scott’s sculptures,” Cornish ventures, “is an exhilarating experience”, but there has not been a full survey exhibition of the New Generation since 1971. Cornish closes his essay by outlining his vision of such an exhibition, drawing solely from the Tate collection, and including Brâncuși’s Fish and Matisse’s Snail, Caro’s Early One Morning, Phillip King’s And the Birds Began to Sing, Smith’s Wagon II or Cubi XIX, and Scott’s Quinquereme and Bird in Arras VI. As Cornish says: “Wonderful!” Let it be! Amen.

• Ten Sculptures by Tim Scott 1961-71 by Sam Cornish is published by Sansom & Co, price £15.