Left: George Kars, Portrait of Berthe Weill, 1933, installation view, Berthe Weill: Art Dealer of the Parisian Avant-garde, Musée de l’Orangerie, Paris, 8 October 2025 – 26 January 2026.

Musée de l’Orangerie, Paris

8 October 2025 – 26 January 2026

by SABINE SCHERECK

In 2023, the groundbreaking exhibition Paris Magnétique at the Jewish Museum Berlin brought the École de Paris to the city. It is still vivid in my memory as it opened a window to the Parisian art scene from 1905-1940 and introduced many Jewish artists, including Georges Kars, Alice Halicka and Béla Czóbel. In the background, one name kept cropping up: Berthe Weill (1865-1951), who showcased their work in her gallery. At the Amedeo Modigliani retrospective at the Museum Barberini last year she played a more prominent role, as she was the only one to arrange a solo exhibition of his work during his lifetime. It was a testimony to her courage to present young, unknown artists whose avant-garde work was bound to shake up the establishment. Her name is connected to the most celebrated artists of the 20th century, including Marc Chagall, Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso. She was also the first to sell a work by the then unknown Spaniard even before he had arrived in Paris. The list of artists, for whom she paved the way and who are now fetching top prices, is long. So, it was high time that this influential art dealer, who had such an impact on art history, was put centre-stage and this exhibition does so formidably.

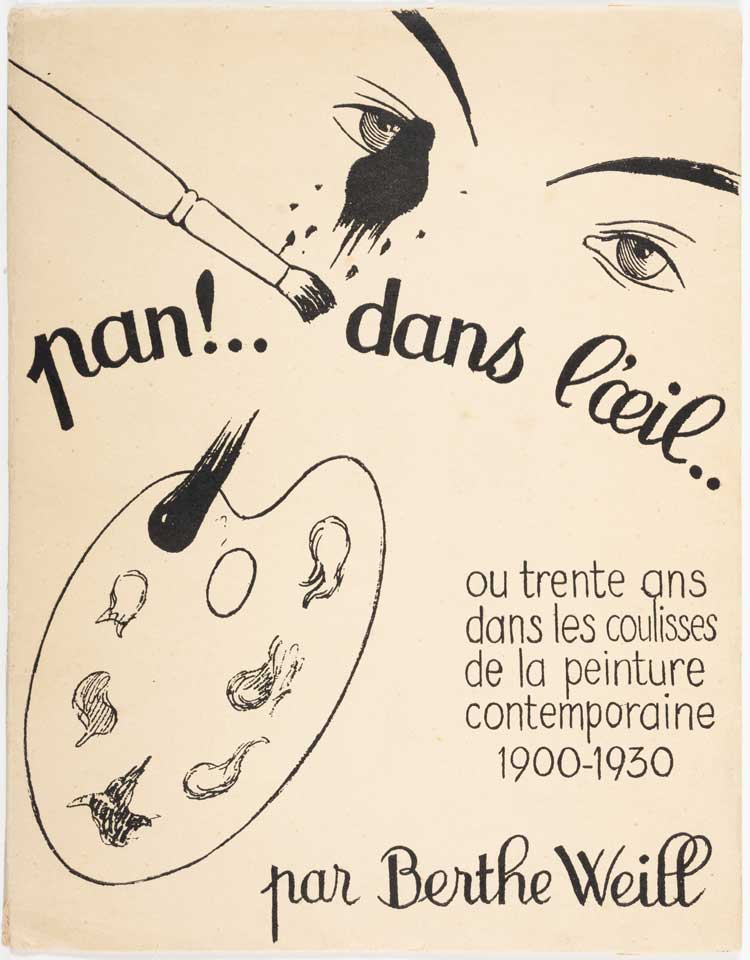

Cover of Berthe Weill’s Memoirs Pan! Right in the Eye, or Thirty Years Behind the Scenes of Contemporary Painting 1900-1930. Copy on paper from the Imperial Manufactures of Japan, Librairie Lipschütz, 1933. © Marianne Le Morvan Collection – Berthe Weill Archives.

Having for so long been reduced to a footnote in art history it – as written by men and mainly about male artists – meant a lot of research was needed and the exhibition is the result of cooperation between the Musée de l’Orangerie and the leading scholar on Weill, Marianne Le Morvan, along with the Grey Art Museum in New York and the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, where versions of this show were presented this year. For Le Morvan and the curators, Lynn Gumpert in New York, Anne Grace in Montreal and Sophie Eloy in Paris, a vital source was Weill’s 1933 autobiography Pan! Dans l’Oeil (translated into English only in 2022, under the title Pow! Right in the Eye!), which revealed what an extraordinary, convention-defying figure she was.

Émilie Charmy, Self-Portrait, 1906-1907. Oil on canvas, 81 × 65 cm. Private collection. Photo: © Studio Gibert. courtesy Galerie Bernard Bouche.

First, she was the only female art dealer in Paris at a time when it seemed unimaginable for women to take on such a role. Second, she was the only art dealer focusing on young artists, which she made clear on her business card, which read “Place aux jeunes”, which can be translated as “Make way for the young”. She also stood out because she supported many female artists, whose work made up about a third of those she showcased. Among them were Suzanne Valadon, who was recently given a major retrospective at the Centre Pompidou, Émilie Charmy, whose portraits also featured in both the Suzanne Valadon and the Modigliani exhibitions, and Halicka and Hermine David, whose work had appeared in Paris Magnétique. It is noteworthy that Weill was also very welcoming to those from abroad: Picasso (Spain), Diego Rivera (Mexico), Samuel Halpert (US), Czóbel (Hungary), Kars (Czechoslovakia) and Chagall (Russia).

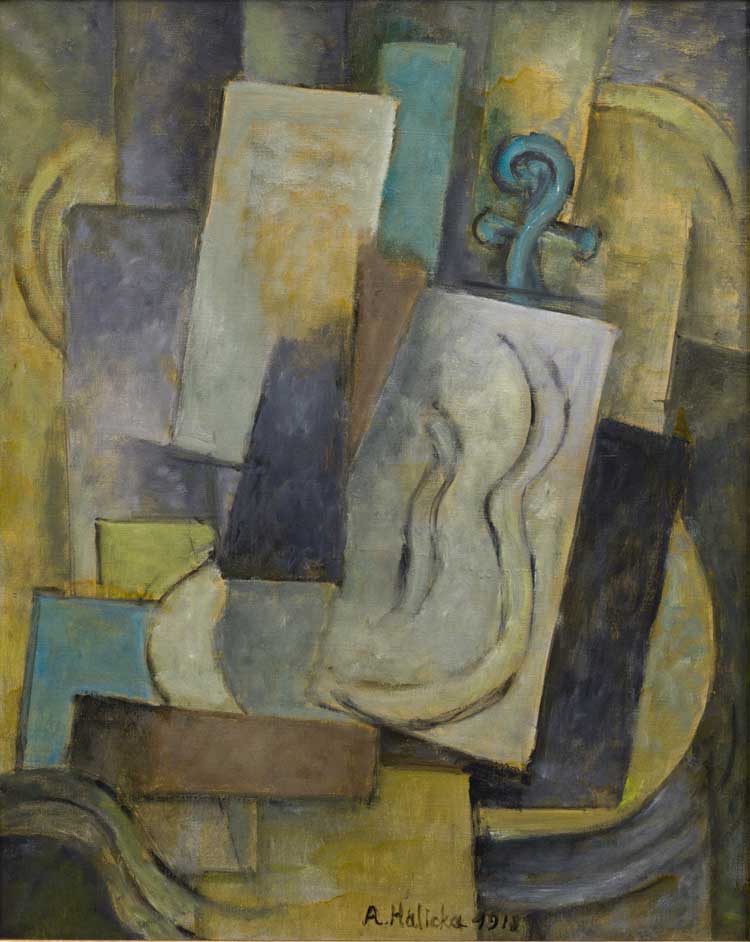

Alice Halicka. Still Life with Violin, 1918. Oil on canvas, 92.5 × 73 cm. Bordeaux, Musée des Beaux-Arts, purchase, 1972. City of Bordeaux, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Photo © F. Deval. © Adagp, Paris 2025.

Her achievement lay not only in the promotion of newcomers, but also in her dedication, steadfastness and the fact that she established herself in a milieu dominated by university-educated men from well-to-do families. Weill, by contrast, was born into a Jewish family, her mother being a seamstress and her father a textile trader. She had six siblings and, at the age of 10, her education ended. As a teenager, she became an apprentice in an antique shop, and it was here that she came into contact with the art world. In 1901, aged 36, she used her dowry to open her own gallery. Wisely, she called it Galerie B Weill so as not to draw attention to the fact that a woman was behind it. She kept the gallery until 1940, a remarkably long time considering she took many risks and ran it without business acumen. For example, if she made a sale for 130 francs, she would give 110 francs to the artist to support him as best as she could. This meant that she hardly managed to keep herself afloat and once the artists had made a name for themselves, they moved to other dealers. She finally had to close the gallery because when the Nazis occupied Paris in June 1940, they forced Jews to shut their businesses. She was additionally at risk as she presented works the Nazis had classed as “degenerate”. She survived the war in hiding but was penniless after it. As a sign of gratitude and to honour her, many of the artists whom she once supported came together in December 1946 to organise a benefit auction. Their donated works raised enough to enable her to live comfortably until she died in 1951.

Astutely curated by Eloy, this exhibition tells Weill’s story through the artists she championed. It begins with Pigalle, the bohemian district in which she had set up her gallery and where, at night, the lights of the cabarets sparkled. Theatre posters not only illustrate the lively quarter but also Weill’s beginnings, as prints were in high demand and she traded them too. This was common practice at the time as the exhibition Art is in the Street, at the Musée d’Orsay, highlighted earlier this year.

![Pablo Picasso, Hetaira [or Courtesan with a Jewel Necklace], 1901. Oil on canvas, 65.3 × 54.5 cm. Turin, Pinacoteca Agnelli. Photo: © akg-images.](/images/articles/w/020-weill-berthe-2025/13a-Pablo-Picasso-Hetaira.jpg)

Pablo Picasso, Hetaira [or Courtesan with a Jewel Necklace], 1901. Oil on canvas, 65.3 × 54.5 cm. Turin, Pinacoteca Agnelli. Photo: © akg-images.

It is stunning how this exhibition brings to light the artistic closeness between Picasso and his fellow artists. For example, seeing Picasso’s Still Life (1901), with its glowing oranges against a strong blue background in an almost impressionistic style, next to Matisse’s First Orange Still Life (1899), also featuring a table with oranges and equally impressionistic, is very revealing. The same applies to Picasso’s Courtesan with a Jewelled Collar (1901), which could be mistaken for a work by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec owing to its sensuous art nouveau lines, while Toulouse-Lautrec’s Clowness Cha-U-Kao (1895) might pass as a quirky Edgar Degas. The pictures demonstrate that the artists cannot be easily identified at that time, as they had yet to find their signature style.

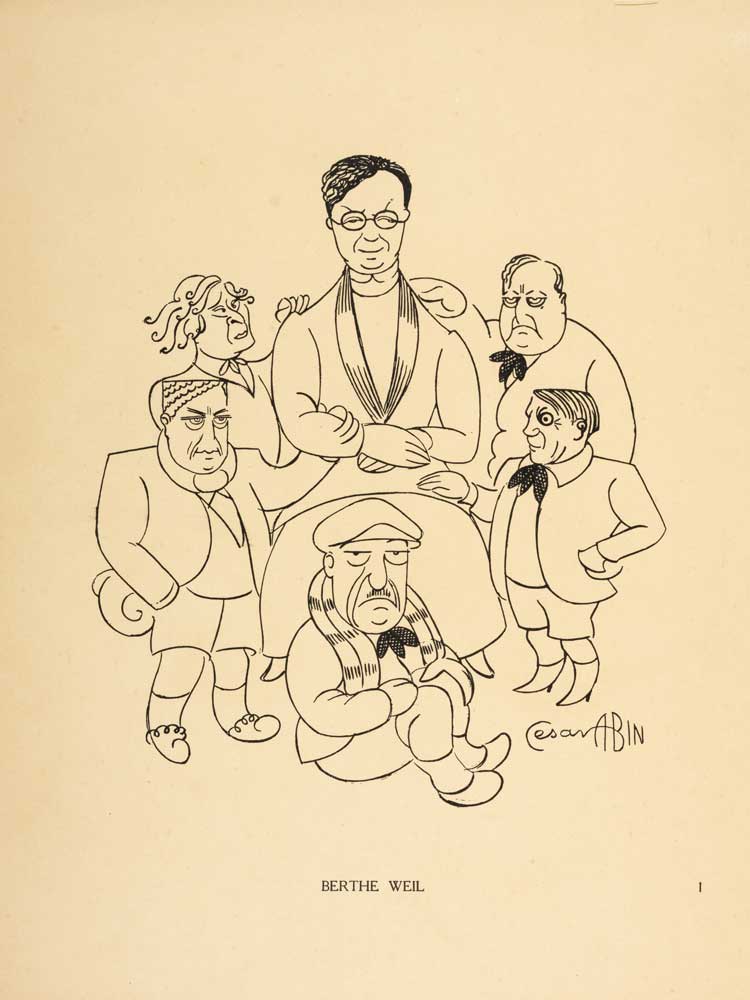

César Abín. Portrait of Berthe Weill Surrounded by Derain, Chagall, Léger, Picasso, and Braque, in Their Faces: 56 Portraits of Contemporary Artists, Critics, and Dealers, with a commentary by Maurice Raynal

Imprimerie Muller et Cie., Paris 18th, 1932. © Marianne Le Morvan Collection – Berthe Weill Archives (gift of Alain Endewelt).

The Parisian avant garde was no uniform art movement, so many different artistic styles came together under Weill’s roof. One of them was fauvism and examples of it are lined up along one wall. Fauvism, defined by its vibrant colours showing landscapes and villages, broke away from traditional perspectives and Weill exhibited this emerging style even before it drew wider attention at the Salon d’Automne in 1905. The images by Maurice de Vlaminck and Raoul Dufy here convey the impulsiveness with which the painters created their work. At the other end of the exhibition hall, diagonally opposite to the fauvist paintings – both in the physical space here but also in terms of where they are on the artistic spectrum – is a display of cubist works, marked by their broken, murky colours, strict geometrical shapes and multiple, fragmented perspectives. The movement is illustrated by paintings by Rivera, Halicka and Louis Marcoussis. The exhibition concludes – in terms of artistic movements – with abstract paintings, including Otto Freundlich’s Composition (1939) with its colourful rectangles arranged in an oval pattern.

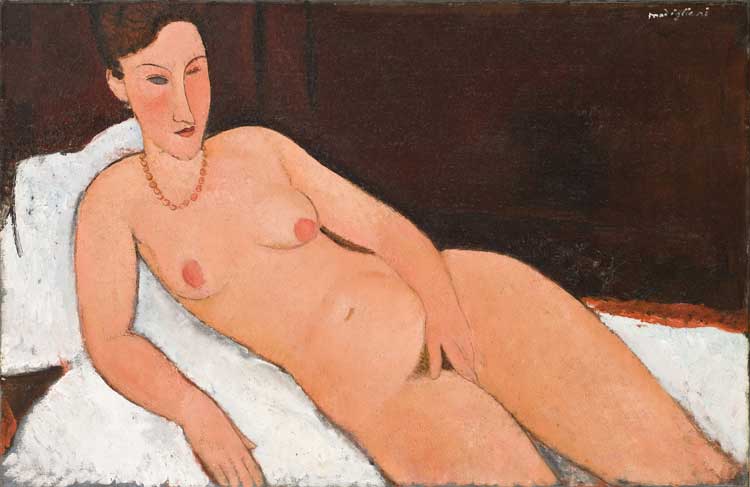

Amedeo Modigliani. Nude with Coral Necklace, 1917. Oil on canvas, 66.5 × 101.1 cm. Oberlin, Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College, Ohio. Gift of Joseph and Enid Bissett. Photo: © Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College, Ohio.

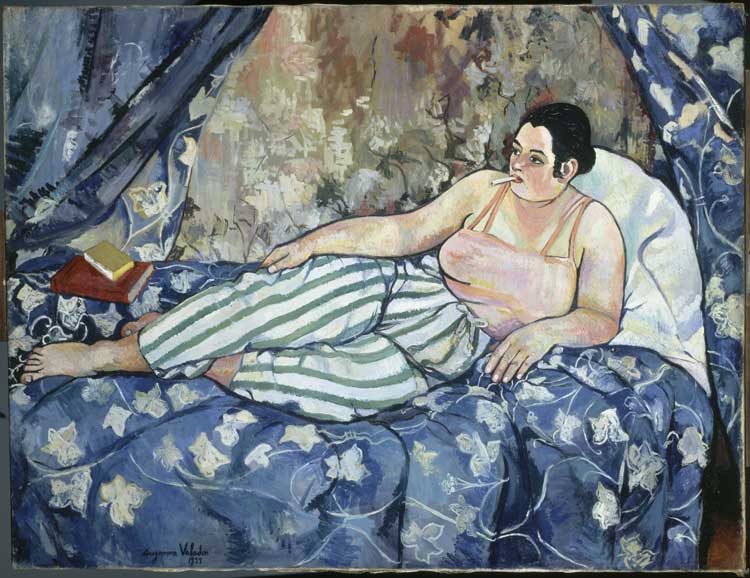

Much prominence is given to the women with whom Weill was good friends: Charmy, Valadon and David. Curatorial ingenuity shines through in the poignant juxtaposition of Modigliani’s reclining woman in Nude with Coral Necklace (1917) and Valadon’s The Blue Room (1923), also showing a reclining woman, but subverting traditional depictions of nudes as seen through the male gaze. Valadon’s woman is lounging on a bed, dressed in comfortable clothes, a camisole and striped pyjama bottoms. She is smoking a cigarette, looks pensively into the distance and has books within reach. She has no intention of pleasing, let alone seducing a man. Instead, she has the aura of an emancipated, modern woman leading a self-determined life. This is stressed by her ignoring the viewer, suggesting no validation from others is needed.

Suzanne Valadon. The Blue Room, 1923. Oil on canvas, 90 × 116 cm. Paris, Centre Pompidou, Musée National d’Art Moderne / Centre de Création Industrielle, on deposit at the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Limoges. Photo: © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, Dist. Grand Palais Rmn / Jacqueline

Hyde.

Weill organised about 140 exhibitions and showcased more than 300 artists. Not all are still household names, so there were some discoveries, such as the black American female sculptor Meta Vaux Warrick, who was a protege of Auguste Rodin, and the French symbolist Odilon Redon and his countryman Fabien Launay AKA Fabien Vieillard, a painter, illustrator and engraver. Launay stands out with a still life of a withering sunflower, painted in 1902, two years before his death. Unlike other still lives in this exhibition, which all embrace the avant garde, this realistic but melancholic depiction of a flower in a homely environment conjures up life in the French countryside.

Georges Kars. Portrait of Mme Berthe Weill, Art Dealer, 1927. Charcoal, signed lower right, 49 × 32 cm. Private collection. Photo © Caroline Coyner Photography.

Apart from the money raised to support Weill in her later years, the way the Parisian art circle cherished her is also reflected by the artists who portrayed her, such as Charmy, Kars and Picasso and by the fact that they affectionately called her Mère Weill (mother Weill), which also suggests “merveille” (marvel) as it rhymes with the pronunciation of her name Berte Vay.

The exhibition, with about 80 works, is part of a series at the Musée de l’Orangerie, which is looking at the art world from a different perspective by putting the spotlight on art dealers and collectors. It previously showed Amedeo Modigliani: A Painter and His Dealer and Heinz Berggruen: A Dealer and His Collection. This is also part of a wider trend: the Liebermann Villa am Wannsee, for example, drew attention to the collectors Felicie and Carl Bernstein this year and the Alte Nationalgalerie in Berlin will next year pay tribute to the well-known art dealer Paul Cassirer, who promoted artists including Max Liebermann. Yet again, this demonstrates how unique and significant Weill is and why this exhibition matters.