-Paris,-place-de-la-Bourse,-5-juin-1914.jpg)

Georges Chevalier (1882-1967), Paris, place de la Bourse, 5 June 1914. Autochrome, 9 x 12 cm. Collection Archives de la Planète, musée départemental Albert-Kahn, dpt des Hauts-de-Seine.

Musée d’Orsay, Paris

18 March – 6 July 2025

by SABINE SCHERECK

Journey through a city today and you will see posters plastered everywhere: on the walls of houses, at bus stops, in train carriages and on dedicated advertising hoardings. They are part of everyday life, so much so that we hardly notice them, let alone credit them with any artistic merit.

In the mid-19th century, however, when a new type of poster emerged in the urban space – illustrated and in colour – its artistic value was indisputable. Art is in the Street makes that very clear as it transports visitors back to the period. At the time posters were created by renowned artists such as Alphonse Mucha, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Théophile Steinlen, but the show also repositions the art form within a wider historical context, raising awareness of how revolutionary it was and that it was part of the artistic avant-garde. Outside the realm of art, the poster also had an impact on other areas: it transformed the cityscape; it helped to develop a thriving advertising industry and a consumer society was born. As a means of mass communication, the poster also sat within the rising mass media, which was particularly prominent in cities. There, advertisements from entrepreneurs of all trades jostled for the attention of passersby, offering, for instance, theatrical entertainment, the latest incandescent gas streetlights, new shopping experiences in department stores, biscuits, beauty products or exotic travel destinations. Posters were used, too, for political purposes to initiate change. From today’s perspective, the style of these posters encapsulates an idealised, visual memory of the belle époque.

Théophile Alexandre Steinlen (1859-1923). Charles Verneau Printing House (Paris). Charles Verneau Posters, La Rue, 1896.

Colour lithograph, 240 × 300 cm. Paris, National Library of France, Department of Prints and Photography. Photo: BnF.

The exhibition, focusing on Paris, opens with Steinlen’s La Rue (1896), a 2.40m x 3m coloured lithograph advertising Charles Vernau, to be precise the posters printed by him. The size in itself was a statement compared to paintings of the same size, which often depicted monumental historical scenes. La Rue shows a mixed crowd of passer-bys, from the washerwoman over the child-minding governess to the refined ladies of the bourgeoisie. The street became a stage to which posters formed the backdrop.

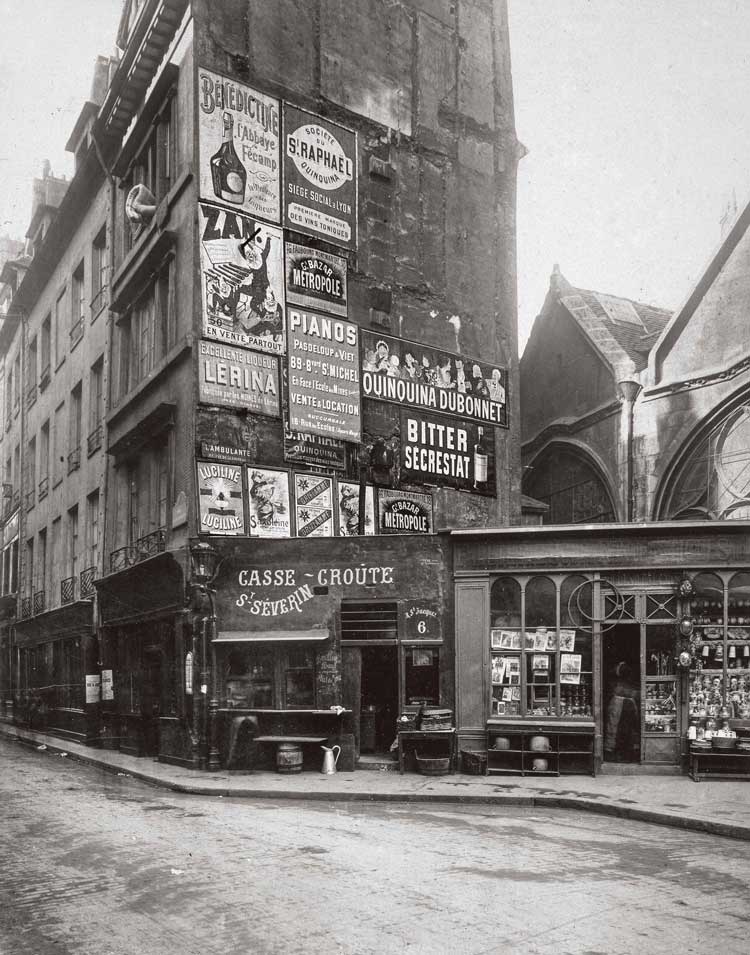

French Photographic Union. Rue Saint-Jacques, buildings 8 and 10, between 1893 and 1898. Aristotype, 29.3 × 23 cm. Paris, musée Carnavalet - Histoire de Paris.

The influx of posters turned the city into a battleground – on numerous fronts. While some regarded the new colourful art as an embellishment of the public space, others feared that the city’s splendour with its fine architecture would disappear behind the masses of advertisements – a “visual pollution”, as one wall text put it. At the same time, posters not only competed with one another for space and attention, but also rivalled one another in their content and messages.

Louis-Robert Carrier-Belleuse (1848-1913). L’Étameur, 1882. Oil on canvas, 64.8 × 97.8 cm. Private collection. Photo: Studio Redivivus.

The entry section is captivating with paintings and photos that bear witness to the new look of the city, among them Louis-Robert Carrier-Belleuse’s painting L’Étameur (1882) and Edouard Vuillard’s La Paris Métro, la Station Villiers (1916). L’Étameur stands out because of its detail, in which numerous colourful but weather-beaten posters are shown covering a wall. Vuillard’s image points to additional insights: when the metro opened in 1900, designated areas for advertising were part of the concept. Protected from adverse weather and benefiting from a continuous flow of people passing through, the station proved an ideal location for advertising.

Edouard Vuillard (1868-1940). Le Métro, la station Villiers, 1916. Painting with glue enhanced with pastel on paper mounted on canvas, 88.5 x 219.5 cm. Paris, Musée d’Orsay, Purchase, 2007. Photo: RMN-Grand Palais (Musée d’Orsay) / Hervé Lewandowski.

Advertising through posters prompted further innovation. In 1868, the French printer Gabriel Morris, who specialised in event posters, began to erect throughout the city so-called colonnes Morris (Morris columns), which were dedicated to advertising and ensured Morris exclusive use. (Visitors from Germany, however, may be surprised that there is no reference to Ernst Litfaß, who invented the free-standing advertising column that bears his name and has been a fixture in Berlin’s streets since 1855.)

Eugène Atget. Place Denfert-Rochereau, 1898. Albumen print, 20.5 x 17.3 cm. Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France. Photo: BnF

The 1870s and 80s witnessed the advent of “mobile” posters, with men or horses pulling “advertising carriages” and “sandwich men” carrying advertisements through the streets. In England, they had already been a regular sight since the 1820s. According to a wall text, on 22 March 1887, 604 poster-bearers were roaming Paris, particularly in lively theatre and shopping areas. The flourishing advertising industry also generated a new trade – the bill poster; in 1908, even a few women took on this job. The Gabert advertising and billposting company employed some, but with mixed feelings. On the one hand, this was marketed by Gabert as “Modern Paris” and “Feminist Paris: The New Professions for Women”; on the other, they were tokens because Gabert regarded this work as unsuitable for women.

How much the spread of the new media gripped society is humorously reflected in short films by George Méliès and the Lumière brothers. Méliès’ silent film shows a policeman patrolling his patch while, unnoticed by him, a man attaches a poster to the wall behind him. Later, another bill poster covers up the first poster with a bigger one, causing a fight between the two men. When they spot an approaching gendarme, they do a runner and the policeman on duty gets a good dressing-down for not having noticed the illegal bill-posting.

This transient nature of posters is brought out by another installation, albeit more by chance than by intention. Five screens show different views of Paris, documenting the endless stream of posters filling the city. The photos are on rotation. Although the locations keep changing, one could easily picture having just one location on each screen and observing how it would change over time, the visibility of each poster on a street lasting only until another poster heralding a newer product replaced it.

Regardless of their fleeting presence and commercial function, posters were taken seriously in the art world and recognised as an artistic genre in their own right. Posters advertising exhibitions of posters in the 1890s document that. Yet, it requires a discerning eye to spot them within the abundance of nearly 230 images spread across the dozen rooms of the show. An interesting footnote is that already at that time, posters had become a collector’s item.

-Maison-de-la-Belle-Jardiniere-1849.jpg)

Anonymous. Rouchon Printing Company (Paris). Maison de la Belle Jardinière,1849. Colour woodcut, 274 × 216 cm. Paris, National Library of France, Department of Prints and Photography. Photo: BnF.

In the exhibition, the positioning of the poster in a socio-historic context is followed by a look at its technical production – how a coloured lithograph was made at the time. A small passageway then introduces the visitor to the consumer temple Maison de la Belle Jardinière – through a poster publicising it, naturally. The presentation of this giant store, comparable to Harrods in London or Macy’s in New York, is a neat bridge to what is to come – the dazzling and inexhaustible world of consumer products that manifests itself in gleefully coloured posters. This is underlined by a change of space: stepping into a large, bright hall with a high ceiling immediately gives a sense of being in such a grand and airy department store, if not outdoors on the street. The array of posters is stunning. Here, they are not neatly lined up in a row anymore but arranged on top of each other. A small section is devoted to chocolates and biscuits, which is complemented by tins and baskets showcasing the world of branding that grew alongside the rise of the promotional poster.

Firmin Bouisset Firmin Bouisset (1859–1925), poster for the biscuits brand Lefèvre-Utile (LU). Section Advertising for Everything and Everyone, Art is in the Street, Musée d'Orsay, 2025. Photo © Musée d'Orsay / Allison Bellido Espichan.

Revelling in this beautiful and quaint imagery that championed sensual flowing lines characteristic of the period’s art nouveau style, it is hard to imagine that these posters were signs of modernity – but they were, in the way they were used as mass communication, their production using the latest technical equipment and the modern lifestyle they promoted, with its cars, bicycles, lights, cigarettes, travel destinations and entertainment.

-Ambassadeurs.-Aristide-Bruant-dans-son-cabaret,-1892.jpg)

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901). Edward Ancourt Printing. Ambassadeurs. Aristide Bruant dans son cabaret, 1892. Colour lithograph, 134 × 95 cm. Paris, National Library of France, Department of Prints and Photography. Photo: BnF.

Leaving the consumer world behind, there are two other major sections to the exhibition: theatre and politics. Paris’s theatre scene was buzzing and always in need of posters to advertise its shows. Often drawn to fellow creatives, artists moved in the same bohemian circles as performers, writers, directors and producers, so connections were formed to theatres and performers alike – as was the case with Mucha and the actor Sarah Bernhardt, and Toulouse-Lautrec and stars of the cabaret. Hence, a collection of Mucha’s and Toulouse-Lautrec’s work make up that section. After a brief nod to the latest arrival in the entertainment world, the film, and in stark contrast to what visitors encountered before, the tone of the exhibition turns much darker when presenting posters engaging in political causes. While posters for consumer goods and theatre shows addressed an affluent bourgeoisie, these posters confronted the viewer – directly or indirectly – with hardship and injustice. Gone are the cheerful colours of a gay bourgeois life: instead, sombre and muted tones dominate. They are used to advertise mainly books and periodicals calling for political action. Steinlen’s poster Le Journal publie Paris par Émile Zola (1897), for example, announced that the newspaper Le Journal published Zola’s novel Paris as a serial.

-La-Fronde-1898.jpg)

Clémentine-Hélène Dufau (1869-1937). Charles Verneau Printing (Paris). La Fronde, 1898. Colour lithograph, 100 × 140 cm. Paris, National Library of France, Department of Prints and Photography. Photo: BnF.

Clémentine-Hélène Dufau’s La Fronde (1898) is of particular note. First, its portrayal of the group of women elicits a feeling of empathy towards them, but it has a feminist quality not found in any other work here, showing women from all social classes, standing tall, looking towards the future. Second, Dufau is one of only two female graphic design artists represented in this show (the other is Jane Atché with her poster for Job cigarette papers). Third, La Fronde, the subject of the poster, was a feminist newspaper founded by Marguerite Durand in 1897: it was written and run entirely by women – which, for me, was an intriguing discovery. It also makes me wonder why the curators, Sylvie Aubenas and Christophe Leribault, could not have devoted some space to women in the poster design industry and perhaps trimmed the consumer and theatre sections instead. Posters from these last two fields are well-known, popular subjects and have been treated elsewhere, for example in the 2017 exhibition Alphonse Mucha: In Quest of Beauty at the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, and in the 2020 show Toulouse-Lautrec and the Masters of Montmartre at the Victoria Art Gallery, Bath.

Clockwise from top left: Jules Chéret, Jane Atché and Alphonse Mucha. Posters for JOB cigarette papers, exhibition view, Art is in the Street, Musée d'Orsay, 2025. Photo © Musée d'Orsay / Allison Bellido Espichan.

The show impresses with its vast amount of printed works, with some unknown and some rarely seen with familiar classics of the genre, such as those by Mucha and Toulouse-Lautrec. Yet its real appeal lies in the exploration of the shape-shifting power the poster had, which is intricately linked to the heyday of poster printing in Paris. This was a decisive period in the city’s cultural history and coincided with the belle époque, which, through these posters, still shapes the image of Paris today.

-Medee-Theatre-de-La-Renaissance-Sarah-Bernhardt-1898.jpg)

Alphonse Mucha (1860-1939). Ferdinand Champenois Printing House (Paris). Médée. Théâtre de La Renaissance. Sarah Bernhardt, 1898. Colour lithograph, 210 × 78 cm. Paris, National Library of France, Department of Prints and Photography. Photo: BnF.