Musée d’Orsay, Paris

9 January – 11 February 2018

by ANNA McNAY

With 2017 marking the centenary of the death of Auguste Rodin, many exhibitions are looking back and celebrating the French sculptor’s life. But what of his student, lover, assistant and contemporary, Camille Claudel (1864–1943), who, after the breakdown of their affair and the death of her father, was committed, by her younger brother Paul, to an asylum, where she lived out her remaining 30 years in misery, dying at the age of 78?

Despite critical acclaim and respect from her peers during her lifetime, her affair with Rodin and her struggles with mental illness have cast a shadow over contemporary interpretations of her work. Her brother, a poet, dramatist and diplomat, to whom she was once very close and of whom she sculpted numerous busts, organised an exhibition of her sculptures at the Musée Rodin eight years after her death, but even he, shortly thereafter, spoke of her life in derogatory terms, saying: “My sister Camille had an extraordinary beauty, moreover, an energy, an imagination, a quite exceptional passion. All these superb gifts came to nothing: after an extremely painful life, it ended in complete failure.”1 And yet there are works that, even today, have not decisively been attributed to either Claudel or Rodin, so symbiotic was their practice and so similar their style.2 Why, then, is she not up there on the pedestal with him?

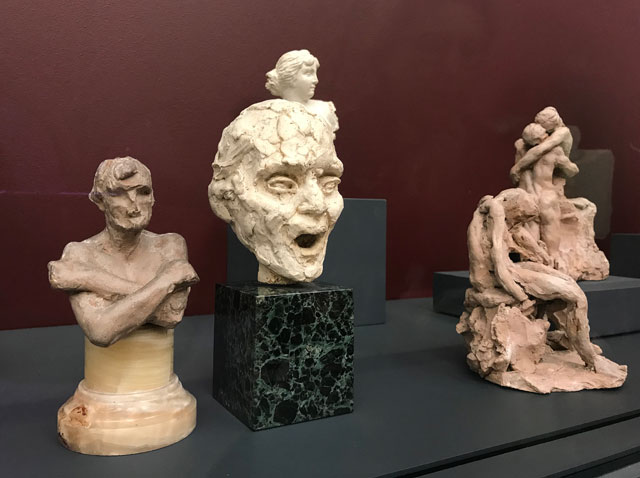

Camille Claudel. Installation view, Musée d'Orsay, Paris. Photograph: Martin Kennedy.

Things are finally changing, and Claudel’s name – to date, largely known to the public through books and films about her woeful life (Bruno Nuytten directed Isabelle Adjani in his 1988 film Camille Claudel, and Juliette Binoche starred in Bruno Dumont’s 2013 film, Camille Claudel 1915), rather than for her work in and of itself – is starting to become better known. March 2017 saw the opening of the Musée Camille Claudel in Nogent-sur-Seine, 62 miles south-east of Paris, a small town in which Claudel lived between the ages of 12 and 15 and where she made her first sculptures. Then, on 27 November 2017, at an auction organised by the Paris-based auction house Artcurial, the French state used a relatively rare law from 1921 allowing it to “pre-empt” works of “national importance” and purchase 11 of her sculptures, consigned by her family, for France’s public museums. These works, in plaster, terracotta and bronze, were on display in the Musée d’Orsay until 11 February and will now be distributed between the museum’s permanent collection and five other museums across France: the Musée Rodin in Paris; the Musée Camille Claudel; the Musée Sainte-Croix in Poitiers; and La Piscine – Musée d’art et d’industrie and the Maison Camille et Paul Claudel, both in the north of the country.

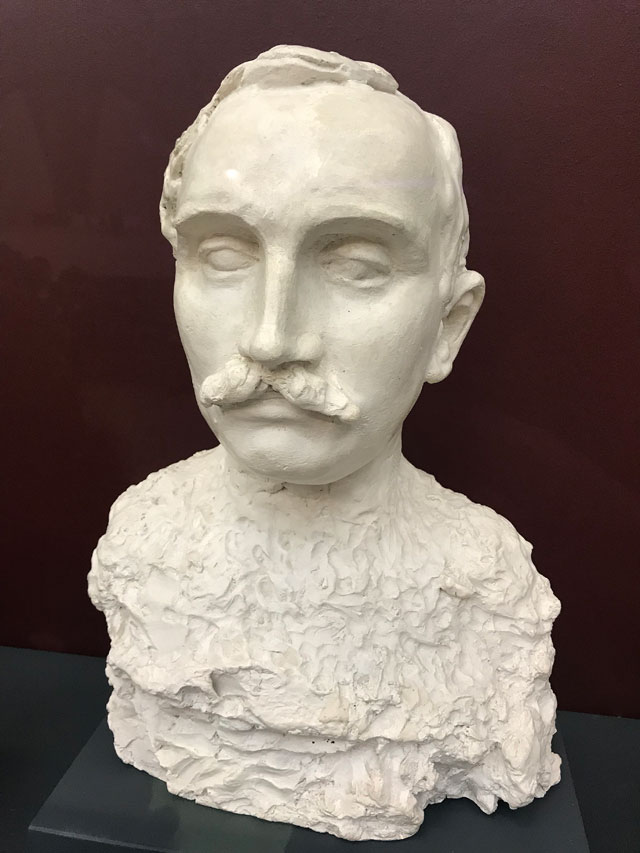

Camille Claudel. Buste de Paul Claudel à trente-sept ans (Bust of Paul Claudel aged 37, study), 1905. Plaster, 39.5(h) x 30.5(w) x 25(d) cm. Poitiers, Musée Sainte-Croix. Acquired with the support of the French National Heritage Fund, the Nouvelle-Aquitaine regional acquisition fund (FRAM), Jean-Paul and Isabelle Brasier, Sylvie and Jean-Marc Juric, two anonymous individuals and an anonymous company, the Mutuelle de Poitiers Assurances and the Société des Amis des Musées de Poitiers

© Artcurial / DR. Photograph: Martin Kennedy.

Among the works that were saved are two busts of Paul, a study for her final sculpture of him, Buste de Paul Claudel à trente-sept ans (Bust of Paul Claudel aged thirty-seven) (1905), in which his dignified, moustached figure emerges from the block, and her much earlier second bust of him, known variously as Mon frère, Jeune Romain and Buste de Paul Claudel (My Brother, Young Roman, Bust of Paul Claudel) (c1882-83), in which he stands proud and honourable, dressed as a Roman soldier.

Camille Claudel. Diane, c1881. Plaster, 18(h) x 10.5(w) x 7(d) cm. Villeneuve-sur-Fère, Maison Camille et Paul Claudel. Acquired with the support of the Communauté d'agglomération for the Château-Thierry area, © Artcurial / DR. Photograph: Martin Kennedy.

From around the same time, Diane (c1881), which depicts the young face of the Roman huntress, further shows Claudel’s early classical style, influenced by her training with Alfred Boucher in Paris. However, La vieille Hélène or Buste de vieille femme (Old Hélène or Bust of an Old Woman) (c1882-85), depicting the head of a family servant, Victoire Brunet, in a tender, intimate and expressionistic manner, demonstrates the range and freedom of Claudel’s early, pre-Rodin work. This head is perhaps also the first instantiation of Claudel’s interest in old age, a theme with which she later spends much time. A plaster model already in the Musée d’Orsay’s permanent collection, Torse de Clotho (Torso of Clotho) (c1893), acquired in 1988, evidences this preoccupation, with its hollow eyes, sunken cheeks, prominent ribs, and drooping empty sacks of skin for breasts.

Because women in Claudel’s day were still not allowed at l’école des Beaux-Arts, she took lessons at the Académie Colarossi, a progressive – private – art school that placed a focus on sculpture, where she was taught by Boucher. When he moved to Florence in 1882, Rodin was hired to teach his class. Claudel, now 18, began working directly with Rodin, 42, often in his workshop. She modelled for him and learned from him, but the influence was not uni-directional, since works signed by Claudel also find their echoes in later pieces by her master.

Camille Claudel. Left: Sakountala, study, c1886. Terracotta 15.5(h) x 11.5(w) x 12.5(d) cm. Paris, Musée Rodin, © Artcurial / DR. Right: Study II for Shâkountalâ, c1886. Terracotta, 21.50(h) x 18.50(w) x 11(d) cm. Paris, Musée d'Orsay. Acquired on funds from an anonymous Canadian donation, © Artcurial / DR. Photograph: Anna McNay.

Claudel’s “first great work” is often considered to be Sakountala (Shakuntala) (originally shown as a plaster model at the Salon of 1888, standing 6ft/1.8 metres tall), and its later bronze and marble versions, renamed L’Abandon (Abandon) (c1886-1905), and Vertumne et Pomone (Vertumnus and Pomona) (1905) respectively. The sculptures are based on Shakuntala, a fifth-century Hindu drama by the classical Sanskrit writer Kalidasa, containing themes of love, rejection and validation. A terracotta study from 1886, which will now rejoin a sketch at the Musée Rodin, was made during Claudel’s period of intense passion for Rodin. Not yet the finalised composition, it depicts Prince Douchanta seated at the feet of his wife, Shakuntala, imploring her to pardon him for having forgotten their marriage. A second study, showing the final composition, is to remain in the Musée d’Orsay. Of course, there has been much written about how the figures in this work parallel Claudel’s affair with Rodin, and to some extent this might well be true, but she has equally taken a classical tale of love and abandonment and successfully transformed it into a compelling visual object. While Claudel was working on Sakountala, Rodin was creating his now iconic The Kiss (begun in 1882), inspired by the story of Francesca and Paolo in Dante’s Inferno. The similarities between the two works cannot be overlooked, nor – and indeed more so – those between Sakountala and Rodin’s Eternal Idol (1889). In 1884, Rodin wrote to Claudel: “My very dearest down on both knees before your beautiful body which I embrace.”

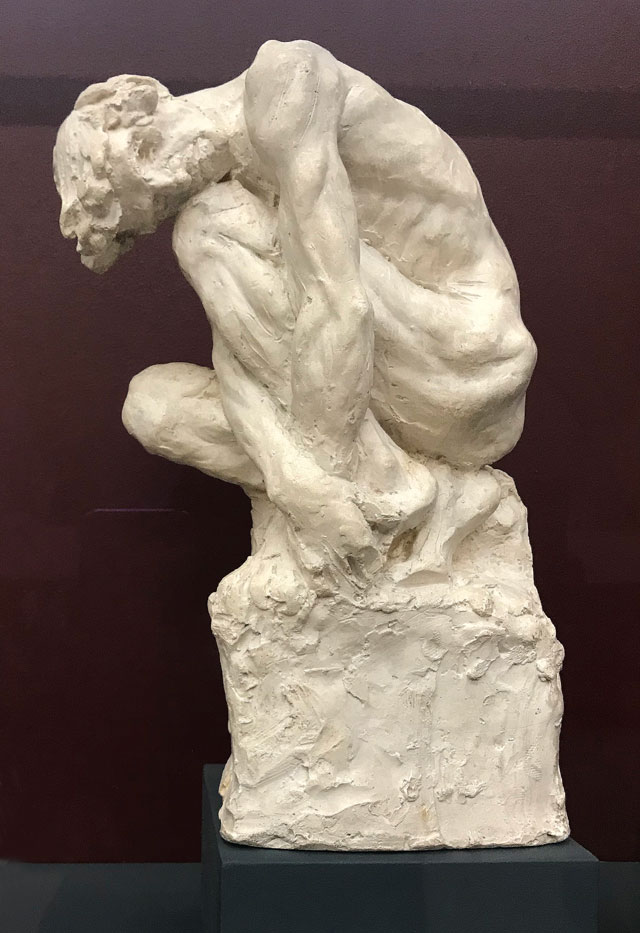

Camille Claudel. L’Homme penché (Man Leaning), c1886. Plaster, 43.2(h) x 16.5(w) x 28(d) cm. Roubaix, La Piscine-musée d'art et d'industrie André DiligentAcquired with the support of the Fonds du Patrimoine, the FRAM of the Hauts-de-France region, the Société des Amis and the Club des Mécènes de la Piscine and thanks to an exceptional sponsorship of the CIC Nord-Ouest

© Artcurial / DR. Photograph: Martin Kennedy.

Other works dating from Claudel’s time in Rodin’s studio include the plaster L’Homme penché (Man Leaning) (c1886), whose tightly self-hugging form, with his musculature every bit as defined as Rodin’s The Thinker (1880) or Michelangelo’s Crouching Boy (1530), radiates a sense of passion and fear, a desperate attempt at self-preservation; the plaster Tête de vieille femme (Old Woman’s Head) (c1890), which portrays the octogenarian Maria Caira, who also modelled for Rodin, with sunken eyes, oversized ears, a swollen nose and wrinkled face; and the terracotta Homme aux bras croisés (Man with Arms Crossed) (c1885). About the last of these, there is still uncertainty as to whether it was made by Claudel or Rodin.

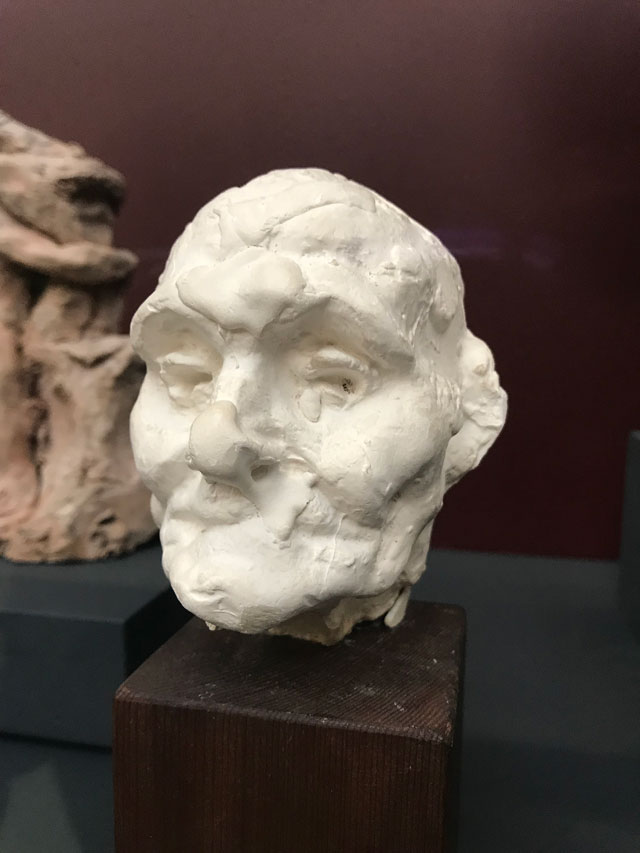

Camille Claudel. Tête de vieille femme (Old Woman’s Head), c1890. Plaster, 11(h) x 9(w) x 11(d) cm. Paris, Musée d'Orsay. Acquired on funds from an anonymous Canadian donation, © Artcurial / DR. Photograph: Martin Kennedy.

The head of Maria Caira was a study for another work by Claudel already in the Musée d’Orsay’s permanent collection: L’Âge mur (The Age of Maturity) (1887), acquired in 1982. This bronze tour de force shows a young girl straining after her lover who is being taken away by an older woman, possibly the personification of death, but, equally, if we return once more to Claudel’s biography, a depiction of her personal circumstances, in which Rodin was abandoning her for his older lover, Rose Beuret.

Camille Claudel. L’Âge mur (The Age of Maturity), 1887. Bronze, 114(h) x 163(w) x 72(d) cm. © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée d'Orsay). Photograph: Martin Kennedy.

In a letter to him dated the previous August, Claudel writes: “It seems to me that I’m so far from you! And that I’m a complete stranger to you! There’s always something absent; which torments me.”3 The plaster of this work was seen by Rodin at the Salon du Champ-de-Mars in 1891 and, although there is no direct record of his reaction, Henry Roujon, the director of Beaux-Arts, proceeded to withdraw his commission for the marble, and Claudel, from this point on, believed Rodin was to blame for all her accumulating woes. There is a French adjective, “éperdue”, which cannot be translated effectively into English, but which means something along the lines of “passionate”, “distraught”, “frantic” and “overcome”, and the works of Claudel from her period with Rodin epitomise this adjective wholesale.

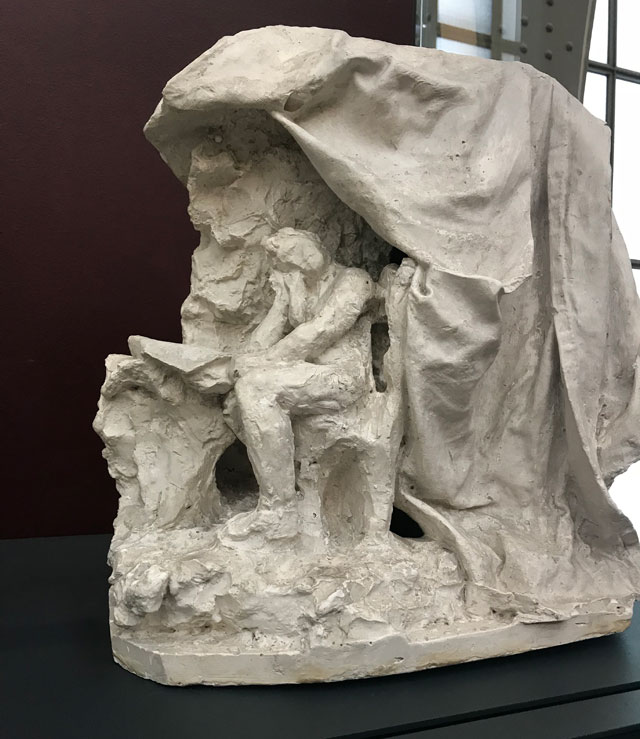

Claudel and Rodin’s relationship ultimately ended in 1898, after a time of drifting apart, furthered by her decision to abort his child in 1892. During this time, Claudel’s style changed – once more – significantly, as she sought to distance herself from their “joint” style, which led to her works for ever being compared with his, mentioned in the same breath as his, and seen as derivative of his. Instead, she began to create intricate, domestic scenes, often draped with some kind of a curtain or throw, as if to turn the scene into a theatre set. Femme à sa toilette, also known as Femme lisant une lettre (Woman at her Toilette or Woman Reading a Letter) (c1895-97), is a beautiful example of this new intimate and personal genre.

Camille Claudel. 2. Femme à sa toilette ou Femme lisant une lettre (Woman at her Toilette or Woman Reading a Letter), c1895-97. Plaster, 39(h) x 40.5(w) x 29(d) cm. Poitiers, Musée Sainte-Croix. Acquired with the support of the French National Heritage Fund, the Nouvelle-Aquitaine regional acquisition fund (FRAM), Jean-Paul and Isabelle Brasier, Sylvie and Jean-Marc Juric, two anonymous individuals and an anonymous company, the Mutuelle de Poitiers Assurances and the Société des Amis des Musées de Poitiers, © Artcurial / DR. Photograph: Martin Kennedy.

In 1899, Claudel moved into her own studio on Quai Bourbon. A decade later, she began to succumb to mental health problems, and, in 1913, shortly after the death of her father, she was committed to a psychiatric hospital in Ville-Evrard an eastern Parisian suburb. Her mother forbade the institution from giving her daughter mail that came from anyone but herself or Paul. In 1914, due to the advancement of German troops, Claudel was moved to an institution outside Avignon, where she died in 1943.

Considering how difficult it was for a woman to be working as an artist at this time, the remarkable achievement of Claudel’s sculpture ought not to be outweighed by the story of her personal life. By dwelling too much on the latter, her works and legacy risk not being valued on their own terms. Equally, however, to understand the deep passion and longing that radiate from her sculptures; to appreciate the progression of her styles; and to realise why she has lain buried for so long, some amount of biographical knowledge is beneficial. Claudel’s great-niece Reine Marie Paris, a specialist in her work, described the opening of the Musée Camille Claudel as an official recognition of “her art and her genius […] Even though it’s late recognition, it’s also a way to separate her from Rodin.”4 These works being made public continues this effort. Both on a personal and a symbolic level – for female artists and for those who battle with mental health issues – the story and legacy of Claudel is an important example of “lest we forget”.

References

1. Rediscovering the Overlooked Talent of French Sculptor Camille Claudel by Cody Delistraty, frieze.com, 28 January 2018.

2. At least for the period of their affair.

3. Camille Claudel: Correspondance, edited by Anne Rivière and Bruno Gaudichon, published by Gallimard, 2014.

4. Rodin's lover, sculptor Camille Claudel, gets museum near Paris by Jake Cigainero, Deutsche Welle, 24 March 2017.