William Mackrell.

by SABINE CASPARIE

Whitechapel Gallery’s The London Open Live 2025 is, excitingly and for the first time, focused fully on live art practices. William Mackrell is one of the 15 selected artists who will be performing on dedicated days between now and September. The preview image of Mackrell’s performance Breaking a Dance (2025) shows the artist in a shiny, glittery suit, in what looks like gold sequins on a blue fabric. His blurred face and contours suggest a wild, abrupt movement. It made me think of a rave, or a participant of Eurovision trying out a sports manoeuvre.

Visiting Mackrell in his studio in north London, however, I am struck by a sense of light and calm. There are works on paper on the walls showing abstract, swirling forms in a coppery gold colour. Two large papers are pinned to the wall like mirror images, forming a wall-sized image of a palm tree, its leaves spread out like angelic wings. There are dried sunflowers on stalks, without petals, their heads a cobalt blue. The sound of a train passing gives the space a soothing rhythm.

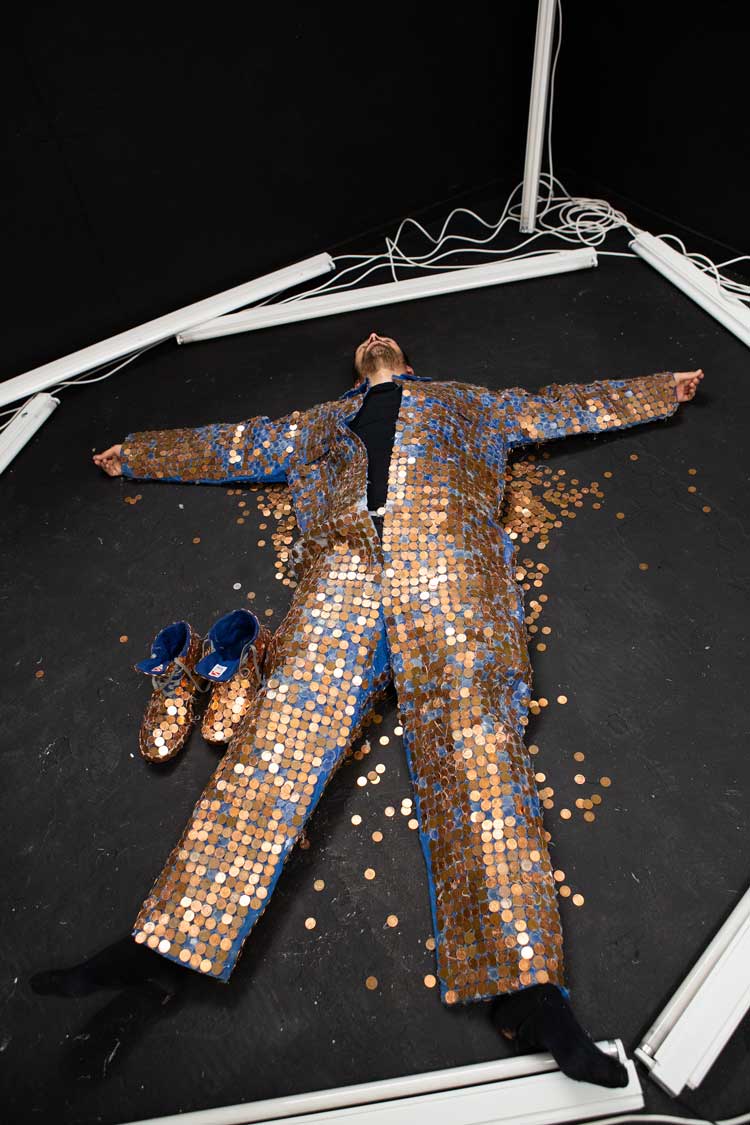

William Mackrell, Breaking a Dance, 2025. Performance, Whitechapel Gallery, The London Open Live 2025. Photo: courtesy the artist.

Like the imprints of sunflower seeds captured inside the copper-coloured swirls, seemingly floating in the wind, Mackrell’s work has moved seamlessly through different media – painting, photography, sculpture, sound and performance – but also through different tones and registers. His most complex performance was the Arts Council-funded Deux Chevaux in 2014, in which the artist staged a procession of two horses pulling a two-horsepower Citroen 2CV car through central London. At a Launchpad residency in France in 2019, the “performance” was fully carried out by nature. Mackrell was struck by the rows and rows of petal-less sunflowers, about to be cut at the end of the summer harvest, and took some into his studio like companions, though not sure at that time what to do with them (many of Mackrell’s works start with close attention to an object or material). Eventually, he left the sunflowers on photographic paper under a rooflight in his studio, lit by moonlight flooding in. The resulting rayograph, Rage Rage Against the Dying of the Light (2020), has a haunting, yet mesmerising quality.

.jpg)

William Mackrell, Rage Rage Against the Dying of the Light, 2020. Rayograph and text framed in UV glass, 245 x 126 cm.

Mackrell obtained a BA in painting at Chelsea College of Art, London, in 2005, and graduated from the MFA fine art programme at Goldsmiths in 2016. His work has been exhibited at Dundee Contemporary Arts UK (2012), Musée National Eugène Delacroix, Paris (2021), and Manchester Art Gallery (2025), where his work was acquired for the collection.

Last year, Mackrell’s Lipstick performance work Divine (2024) was acquired by Muzej Lapidarium Croatia, where it was recently re-presented at the museum in its show Museum as Muse. Mackrell’s exhibition Exposed Tender is currently showing at Lungley Gallery in London, his third solo exhibition with the gallery. Larger and smaller Lipstick paintings are paired with two “Sleep Pieces”: lightbox installations of a mattress and pillow, carrying imprints of his body in sleep. The gallery is bathed in a warm red light, suggesting danger and desire at once.

Studio International spoke with the artist in his studio before the opening of The London Open Live, where Mackrell will be performing his new work Breaking a Dance.

Sabine Casparie: What performance will you be doing at Whitechapel Gallery?

William Mackrell: I will be wearing my studio overalls and shoes, covered head to toe in penny coins. The performance begins with me trying to move and eventually beginning to dance under this quite colossal weight of coins, which might start to shed and fall away. The whole piece is surrounded by fluorescent lights at the end of their lifespan. The lights are sourced from industrial workspaces and artist’s studios near the Whitechapel Gallery and further across London. There is beauty in the way the coins glisten, like the pearly kings and queens of London’s East End with their amazing silver embroidered outfits. At the same time, there will be a sense of fragmentation and inconsistency: the lights will be flickering and pulsing in their natural state of breakdown. I am thinking about London and the disappearance of spaces and objects like fluorescent lights and coins.

William Mackrell, Breaking a Dance, 2025. Performance, Whitechapel Gallery, The London Open Live 2025. Photo: courtesy the artist.

SC: Has the city of London always been influential?

WM: I have always lived here – I can’t seem to escape! The locality charges the work. I am constantly trying to grapple with the city, trying to navigate its intensity, its constant change. London demands so much of the body. I would like to see the performance as radiating that feeling of living in London: trying to keep going under a certain weight and exhaustion, in the forever trembling city. The performance in the Whitechapel has its own time: I don’t know when the lights will falter and stop. I am very interested in rhythms: cycles of things, the rhythms of my body, of society. But rhythms can also be inconsistent: pulses, explosions. We are in a period of uncertainty, and I feel there are a lot of emotions that are difficult to express.

SC: You studied painting, and it sometimes appears in your work, but you don’t seem to use a brush. Was it something that you intuitively felt, that painting wasn’t your medium? Or was there a rational idea behind it, like wanting to stretch the medium?

WM: I think it came from the heart. I felt like the brush was in the way. I wanted to have the immediacy of emotion, but I also wanted to speak of silence, and I felt that things started to get very boxed in with traditional painting. At Chelsea I got interested in everything else going on: sculpture, photography, performance, sound. I came back to painting a lot later, in my Lipstick series that started in 2013, but my mouth became the brush. But mostly I want my work to avoid being cornered by medium, and not to become formulaic. I move between materials and work with a sense of their unfixed relation to medium, blurring these boundaries altogether. It is important to me that the works themselves challenge the language of genre. Not to try and be difficult, but to experiment and surprise. Opening doors instead of closing them.

William Mackrell, Divine Loop, 2025. Lipstick on Heritage white paper, lime wood frame, UV glass, 133.5 x 95.5 cm. Photo: courtesy Agnese Sanvito.

SC: I have always found performance a tricky medium: you are exposing yourself, you are very vulnerable, there is risk involved, and it is hard to sell. What led you to do performances and what was your first performance like?

WM: After coming out of Chelsea College of Art I got really excited about the performative qualities of everyday objects, and I started imaging what would happen in certain unusual, set-up scenarios. My first performance was 1000 Candles in 2009 at Departure Gallery: a temporary space operating from a vast 100,000 sq ft (9,300 sq metre) warehouse in Southall, London, which has since closed. At the time I didn’t really think about the work as a performance but more as an action: the act of trying to light the 1,000 candles. While doing it, I realised how difficult it was, because the force of the heat was very hard to reach over, and the candles started creating their own swirling vortex of air and would blow themselves out into patches. This then led to me later making an eight-hour video of the live work from fully near lit to burnt out. In 2012, I was part of a three-person show, Infinite Jest at Dundee Contemporary Arts, where I presented 1000 Candles as a live work, film and photograph across different galleries in the museum.

SC: What was it about the difficulty that attracted you?

WM: I have an interest in dissecting the myth of Sisyphus, this repeating loop trying to roll something up a hill only for it to roll back down – the persistence in the seemingly impossible. Extending on from 1000 Candles, questioning the potential of candle power, in the second performance, Deux Chevaux I was attracted by the concept of horsepower in a car, but then it also became about doing something very challenging. But also, I find a certain poetry in objects having their own rhythm: objects, like engines, having a life span, a horse that decides to munch in a hedge and not wishing to co-operate and each light in 1000 Candles having its own shine, pulsating in a certain way. Dan Flavin wrote in one of his essays: “The lamps will go out (as they should, no doubt).” I love this idea that maybe he was alluding to his own bulbs that couldn’t last for ever; that for me is where the conversation begins. There is something there about salvaging time and a whole world that can exist inside a fleeting moment.

William Mackrell, Sleep RED, 2025. Carbon paper, mattress, acrylic case, LED lights, 196.5 x 94.5 x 20 cm. Exhibition view, William Mackrell, Exposed Tender, Lungley Gallery, 2025. Photo: courtesy Agnese Sanvito.

SC: Like fighting the futility of life?

WM: It’s not supposed to be sad. I see it more like an exorcism of feelings. Something beautiful and sinister at the same time. Mark Fisher, who taught visual cultures at Goldsmiths, introduced me to the concept of hauntology: the present can be occupied by the past and the future. In my current show at Lungley Gallery, I dismantled my old childhood bed, which was later used by my father, and on which I slept again after he died last year. I decided to record the imprints of my movements during sleep, on carbon paper that I attached like a bedsheet over the mattress and pillow. My resulting sculptures at Lungley Gallery display the bedsprings with the carbon paper on top, lit from within. I was attracted to use a red paper that would give a certain pink-reddish warmth to the room and radiate the other works and feel very bodily. It was important that the work wouldn’t feel cold and sad – more a celebration than a commemoration. My dad always was a great supporter of my work: we had lots of conversations, and he never missed an opening! I like to think of the red light also charging the air with the breath of liveness and performance, as do the Lipstick paintings displayed on the opposite walls. Mark (Lungley) and I came up with this idea to bring the sleep and lips works together – I really appreciate Mark’s vision, sometimes I feel that galleries are not given enough credit for the curatorial input they provide to artists.

Exhibition view, William Mackrell, Exposed Tender, Lungley Gallery, 2025. Photo: courtesy Agnese Sanvito.

SC: There is a sense of layering: literally, putting surfaces over each other, but also metaphorical in the sense of layering time. Are you interested in metaphysics?

WM: I am not very scientific, but I am interested in the effect of materials. I like things to be what they are, but I am curious when one material radiates life out of another. All my work goes back to this idea of disassembling things and putting them back together in a minimal way. I like to leave space for people to step in as we all have very different emotional experiences. There is already a lot to process in life, so I enjoy that my work is difficult to pin down, both in terms of materials and its meaning.

SC: You mention the word “minimal”, and it seems that a lot of your works on paper verge on the abstract. Are you interested in abstraction per se?

WM: I think abstraction is there, but it comes from an interest in focusing on what matters and trying not to overcomplicate things. My studio is calming – the light, the view of the park, the sound of the railway – and it helps me to filter out the noise of life. It is similar on a residency: I like working with the specifics of a place. Going back again to art school when I was trying to paint, there was so much happening, and I couldn’t find a way through: too much choice, too many materials, too many brushes. Like being at a restaurant where there’s too much on the menu.

SC: It is almost as if you work the other way around. Abstraction is often a form of reduction, whereas your work seems to start with a really small thing that you then try to stretch out. Does that resonate?

WM: Yes. I do like the idea of something that can be singular at the beginning and then it can grow. It’s almost as if that thing is building its own momentum. In my Hair Etchings, I don’t find the photograph of the back of someone’s head particularly interesting, but when I start scratching the hairs, they start to change shape: they look more like electric wool and the image becomes almost holographic. I start with scratching one tiny hair, but by the time I have covered all the hair on a large photograph, it’s not about the single scratch any more, it’s about the larger idea – the hair becomes a kind of landscape or a population and the image starts to take on a certain depth. Similarly, in my upcoming Whitechapel performance, I like that the penny, the smallest coin, has been accumulating on my overalls, and that when I move, these pennies will start to show their differences: some coins have a coppery green patina as if they have been in the water, some coins might be more reflective than others, there might be a few euro coins that slipped in. There will be a lot happening in the coins, the lights and the movement, but I don’t want the work to be about one defined narrative.

.jpg)

Exhibition view, William Mackrell, Rage Rage Against the Dying of the Light, Lungley Gallery, London, 2020.

SC: Let’s talk about the use of photography in your work. Photography has traditionally tried to capture a likeness, whereas your work seems to capture something more elusive: an energy or a trace. What interests you about the photographic medium?

WM: I started processing my own films and working in dark rooms from when I was very young, and I liked the space: the red light, the darkness, the feeling of seeing things slowly emerge. I have tried to keep certain elements of photography in my work: ideas of exposure and definition or the blocking of light in cyanotypes. I often use a different medium, like spray paint, to mimic the properties of photography. I would say that I use the ideas of photography more than the techniques: the indexical mark-making in the Lipstick performances, the capturing of light in 1000 Candles and Breaking a Dance. I think a lot about photography as breath: something passing through something else and leaving its heat on the paper.

SC: I like that idea, almost like an abstract performance. But maybe I am trying to label something that is more elusive, open-minded?

WM: I don’t like pinning things down too much. I do connect to abstraction and hauntology, and also mythology, but I like to see these as concepts that the work ricochets off but doesn’t try to speak of directly. I think things can become clearer when they have space to breathe. I do like to be clear about what the materials are. An immediacy with materials – and by extension, with ideas of touch, trace or absence – that is really important to me.

SC: An alchemy!

WM: Yes, there certainly is an element of that. The material is leading; it is telling me what to do. I try to guide the material to tell its own story, which is already there. I like coming up close to things and then giving them space to reveal themselves, and for people to really look and question what they are seeing. Is the paper black or white? Is it a cyanotype or a spray painting? Also, my work has become more colourful and warmer. Maybe it’s because I am a father now. But I also feel that there isn’t enough warmth in the world.

William Mackrell, Divine, 2024. Lipstick performance work. Gallery view, Muzej-Lapidarium Croatia.

SC: To come back on your performance work, you seem to have moved from animating objects to using your own body. Have you become more confident putting yourself in your work?

WM: I had done Lipstick performances before, but then I stopped for a while. The context in which I was sometimes performing felt so wrong: at art fairs and events, I felt that they were often just staged for the show value. I was excited when I read the open call for the Whitechapel, because I could really sense that it wanted to give performance a proper space and a platform. There will be conversations happening around it: the fact that live performance had been hit by Covid, for example, or that it is a difficult medium to make and collect. I thought: “I want to be part of this!”

SC: Do you feel there is a performance art scene in London? Do you connect with other performance artists or is performance a more insular activity?

WM: I am a bit wary of the phrase “performance art” – it can become performance just for the sake of it. I see performance as something more organic flowing from the artist’s practice. Ursula Krinzinger, my gallerist in Vienna, has been supporting performance from the 1970s, and gave artists such as Marina Abramović and Paul McCarthy a platform very early on. There is an interesting scene in Vienna right now. Pati Lara the director of The Ryder Madrid, who I also work with, has had a strong performance platform since when she began with Ryder in Herald Street (east London) back in 2015. At the moment, I feel a bit disconnected from a broader conversation and so I’m excited about the Whitechapel exhibition. I am so curious to meet the other artists – It’s important to support each other. Hopefully, it will lead to a wider dialogue on performance art in London.

• William Mackrell: Exposed Tender continues at the Lungley Gallery, London, until 28 June; Breaking a Dance, part of The London Open Live 2025 at the Whitechapel Gallery, takes place at 7pm and 8.30pm on 28 August.