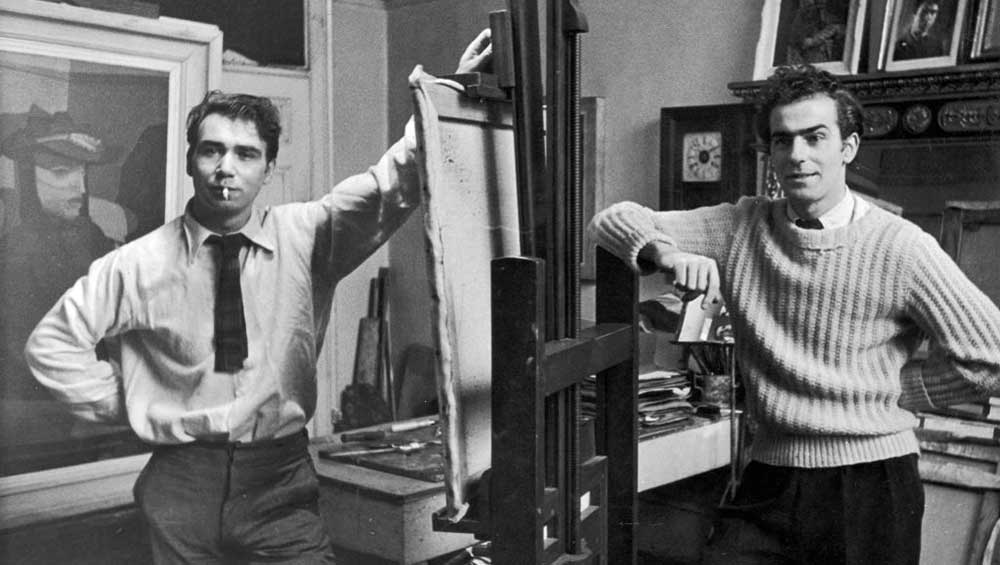

The Two Roberts, Photo: Felix Man, Courtesy of Getty Images.

Charleston, Lewes, East Sussex

15 October 2025 – 12 April 2026

by TOM DENMAN

The story is about a couple, both painters, both men at a time when homosexuality was illegal, similarly different in a way that the one classically completed the other. Robert Colquhoun and Robert MacBryde – or “the two Roberts”, as they were known, which is also the title of the new novel (2025) by Damian Barr, curator of this show – were both born in the west Scottish county of Ayrshire and came from working-class backgrounds. They met, as scholarship boys, in their foundation years at Glasgow School of Art in 1933. Thereafter they were inseparable, a fact that was recognised early on: in 1938, when Colquhoun won a travelling stipend – narrowly beating MacBryde in the competition – the school’s chairman of governors secured the money to give his boyfriend a second award. Later, at the start of their London glory days in 1942, the critic Wyndham Lewis would describe them as “one organism”. Although Edinburgh’s National Galleries of Scotland gave the Roberts a presentation in 2014, this is their first major show in England – the country in which they spent most of their working lives – since their 1962 retrospective, which omitted the then-illegal personal element of their relationship.

Ian Fleming, The Two Roberts, Colquhoun and MacBryde, 1937–1938. Oil on canvas. The artist’s estate, Glasgow School of Art.

Aside from acknowledging two once-famous, subsequently forgotten artists who remain a fascinating, poignant example of art dovetailing with love and life, the exhibition is striking for its novelistic curation. Barr’s fondly personal wall text narrates a tale of love, fame, drunkenness and tragedy. This forms a backdrop to a thematic arrangement of drawings and paintings which, rather than offer any kind of chronological progression, characterises the roles the artists played. In his still lifes, for instance, MacBryde “gives us a glimpse into their home, serves up delicious eyefuls of rationed foods, and shows us what he’s cooking for his man”. It is a biographical, charmingly licentious resurrection of two figures that marries well with their painterly theatrics which, in turn, seem to correspond with the enigma of the self, particularly the potential need to mask or codify one’s own outlawed sexuality.

Dominating the opening section is not a work by either artist, but rather a portrait of the pair at Glasgow School of Art (1937-38) by their tutor, Ian Fleming (the painter, not the more famous novelist of 007 fame). Both are seated, the broody, high-cheekboned Colquhoun slumped in his chair (in the wall text, Barr describes him as “shy and introverted or, when drunk, potentially explosive”); the more gentle-featured MacBryde (“his extroverted opposite”) sat next to him, his tender-eyed gaze narrowly missing his boyfriend’s face, his hand’s close pictorial proximity to his forearm. Whether or not Fleming intended coded recognition of their romance, we have a sense of their deep personal bond.

Robert MacBryde, Apples on Paper. Oil on board. © the artist’s estate. Pallant House Gallery, Chichester.

And it is hard not to see this image as containing a secret, surrounded as it is by so many depictions of masquerade: MacBryde’s The Singing Man (c1945-46), who wears a kind of Greek mask, Colquhoun’s Masked Figure: Venetian Carnival (1950) and Puppet Show, Modena (1951), and even his oddly carnivalesque The Potato Diggers (1946). This could be little more than a love of cubism – in their day MacBryde was known as MacBraque and Colquhoun as McPicasso. But the artists, especially Colquhoun, who was drawn to the human figure more than MacBryde whose main genre was still life, are more masky than Picasso ever was. Even Colquhoun’s relatively naturalistic pencil drawing of himself as a soldier during the second world war, The Army Haircut (1940), is highly mannered, as if expressing the diabolical effects on his soul of being forced into military service – and separated from MacBryde: raging eyes, arched eyebrows, an elven ear.

Exempt from the army because of tuberculosis, MacBryde used the connections he was making in the London gay scene – especially Peter Watson, a millionaire philanthropist and founder of the influential magazine Horizon – to bring Colquhoun home in 1941. This decade was the Roberts’ heyday. They rose quickly to fame and acceptance among the fabled crowd of virtuosic drinkers – including Lucian Freud and Francis Bacon – at the Colony Room in London’s Soho. Most of the show’s more substantial paintings date to after their eviction from their London studio – for having “drunk orgies”, the landlord put it – in 1946, as they declined into impoverished nomadism, even if they continued to enjoy a degree of recognition. Colquhoun, for example, had a retrospective at Whitechapel Gallery in 1958.

Robert Colquhoun, Woman with a Goat. © the artist's estate / Bridgeman Images. Victoria Gallery & Museum, University of Liverpool.

The abounding flavour is theatrical wit, tinged with sorrow. We can easily imagine the couple indulging in a bit of wordplay in MacBryde’s Man with a Melon (1952) – painted around the time the Roberts were lodging with the poet Elizabeth Smart in Essex – in which a loosely clothed, sad-eyed Pierrot is slumped at a table beside the eponymous fruit, apparently acting out an allegory of “melancholy”. This might make us wonder what it really meant for them to be “with a melon”. A stinking hangover, perhaps? And if the melon is a sad fruit, then this puts a playfully sinister spin on Colquhoun’s Melon Seller (1950), in which a similar figure, possibly a red tear in his eye, skins the fruit with a threatening blade. His exaggerated gesture, along with the geometric backdrop of deep purple and green, dusky blue and jet black, lends the image a musicality – transforming the melon into a sad-sounding, ominous instrument the vendor is strumming.

The use of earthy, warm colours, the constant sense of a beating human heart, is perhaps most of all what distinguished the Roberts from the exuberance of, say, Picasso or Bacon. To take a magisterial example, in Colquhoun’s The Goatherd (1948), the man’s heavy-nosed, leathery face which, as usual, resembles a mask – the eyes eyelets through which the “real” goatherd peers, let alone his purple-dotted cheeks and lips – all have a certain clownishness about them. But the dirty hues, and the ravaged, almost skeletal appearance of the man’s chest, and his abject slump as he leans back against an incongruous cuboidal form – a coffin perhaps, or an out-of-context pub bar – convey genuine, deep sadness. MacBryde’s Still Life, Autumn (c1950) is a proto-cubist depiction of a cucumber, cantaloupe and a loaf of bread, nicely laid on a wooden chest. One drawer is half open, its handle inviting us to take part in the illusion which, if we decide to see the keyhole as symbolic, is also an enigma. The overriding feeling is one of homely comfort, generated by the claret wall and sweet-pink wrapper cradling the fruit and veg. This is an abstraction, yes, but one that is intimately relatable.

-the-artist_s-estate,-Bridgeman-Images.jpg)

Robert Colquhoun, Bitch and Pup, 1958. Oil on canvas. © the artist’s estate, Bridgeman Images. City Art Centre, City of Edinburgh Museums & Galleries.

The Roberts painted in a similar style, a kind of humanist proto-cubism, and it is interesting to see how they might have influenced each other – such as in the looming shadows in the middle of MacBryde’s Still Life with Calf’s Head (1948) (note also the scrotal tap above the sink) and Colquhoun’s Bitch and Pup (1958). The intruding shadow (a canonical, comparable example of which is in Picasso’s The Shadow of 1953) could be ours, inviting us to peel the potatoes and handle the severed head, and to observe, at close quarters, the canine mother and child. The show includes one actual collaboration, their designs – each drawing signed by both – for the costumes and set of Léonide Massine’s Scottish-themed ballet Donald of the Burthens, staged at The Royal Opera House in 1951. Colquhoun died suddenly, in his studio in London’s Museum Street, in 1962 at the age of 47. After this MacBryde hardly worked, and, in 1966, he was killed by a car in Dublin.