Beyond the Visual, installation view, Henry Moore Institute 28 November 2025 – 19 April 2026. Photo: Joanne Crawford.

Henry Moore Institute, Leeds

28 November 2025 – 19 April 2026

by ANNA McNAY

“Go into the exhibition, touch everything!”

How often does a curator greet you like this? I’d hazard a guess at not very often – if at all. But things could be starting to change.

After all, Henry Moore told the photographer John Hedgecoe in 1968: “One likes people to want to touch, because touch is a part of your understanding of three-dimensional form. You don’t know roughness and smoothness, and you don’t know roundness and sharpness and all those. You’d know it much more intensely if you’ve felt it … Having these notes ‘Do not touch’ in the sculpture exhibition … Well, I want the people to touch … Touch is a part of your understanding of form.”1

While Moore was addressing his comment to everyone, blind and partially sighted gallery and sculpture park visitors are a particular category of people for whom touch is not just a part of their understanding of form, but pretty much is their understanding of form.

Beyond the Visual, installation view, Henry Moore Institute 28 November 2025 – 19 April 2026. Photo: Joanne Crawford.

David Johnson, one of the artists in the Henry Moore Institute’s groundbreaking exhibition, Beyond the Visual, writes in the book of the same title, published to present outcomes of the same research project: “With blindness there is an increased sense of flux or transience when encountering objects that are usually experienced as being ontologically present and static. With visual impairment, and when experienced by momentary touch, objects often take on a more transient quality. With the absence of healthy vision with which to check from a distance an object’s continuing presence, then that object’s ontic presence becomes subject to doubt in the mind of the blind beholder.”2

The exhibition is the culmination of a three-year research project the institute has led in partnership with the University of the Arts London and Shape Arts. It features 16 international artists and includes historical and contemporary works, and, as its co-curator, Clare O’Dowd, says: “Every object in there is open to experience in so many different ways. We’re laying down the gauntlet here. As far as the institute goes, I can tell you that we have been on possibly the steepest learning curve ever. It’s kind of a watershed moment in that this exhibition has been delivered and we have all these measures in place.” These measures include every object being accompanied by an audio description – something the institute began to implement from the moment it came up in discussions with the project. They also have tactile flooring instead of barriers around the works. And, most importantly, every object is there to be touched. In fact, not just touched, but many of them employ combinations of four of the key senses: touch, sight, sound and smell.

A visitor and her Guide Dog with Aaron McPeake, Rings, 2025 in Beyond the Visual at Henry Moore Institute 28 November 2025 – 19 April 2026. Photo: Joanne Crawford.

Take, for example, two works by co-curator Aaron McPeake – Icelandic Landscapes (2007-24) and Rings (2025). The latter comprises five bell bronze rings of different sizes, hanging in the form of a horizontal cone. Each ring has a clapper and can be rung like a bell, each with its own unique sound. As McPeake describes in the accompanying audio description: “The metal that they’re made from, which is bell bronze, 80% copper, 20% tin, when it’s handled, reacts with the oils in one’s hand or the oils in one’s skin and leaves a scent. So, this work’s visual. It’s haptic. It changes temperature, if you hold on to it longer. It’s sonic. It’s vibratory. It’s with the sound element. And then there’s also the smell element.” Honestly, I couldn’t smell all that much, but the Icelandic Landscapes had a deep earthy scent.

David Johnson, Inhibition: Beyond the Doubt of a Shadow, 2025. Installation view of Beyond the Visual at Henry Moore Institute 28 November 2025 – 19 April 2026. Photo: Rob Harris Photo: Joanne Crawford.

Similarly, one of Johnson’s two pieces, Inhibition: Beyond the Doubt of a Shadow (2025), a crude description of which would be a table and stools with chewing gum stuck to the underside, also smells strongly of peppermint (although I didn’t notice this until I was told, showing me how much I might be missing out on by not having all my senses tuned in). A more generous description notes that the “chewing gum” is silicone, and that the pieces are stuck on so as to spell out “inhibition” in Braille. Inhibition, Johnson notes, is the opposite of exhibition, and “the whole piece is about inhibited art. It’s about hiding it rather than exhibiting it. It’s out of sight. It’s invisible, inhibited and only available to touch.” Expanding on what he writes in his book chapter, Johnson continues, that, for a blind person, the underside of a table is just as prominent as the top of it. “So, I decided to put something there. I also wanted the ‘ugh’ factor,” he says laughing, introducing a playful aspect to the piece, which is otherwise designed to deliver a serious message around inclusion.

-(c)-Rob-Harris-(3)-.jpg)

Serafina Min, Pass Away, 2025 in Beyond the Visual at Henry Moore Institute 28 November 2025 – 19 April 2026. Photo: Rob Harris. Courtesy of the artist.

Serafina Min’s Pass Away (2025) is another piece with a serious message. The objects that the artist has made have been placed inside an opaque box and are hidden from view. The only way to experience the artwork is through the audio description, and this attempts to describe the three wax pieces as “explaining death to a blind child”, when you can’t simply say that you won’t see someone again or that they have gone away. Min describes death “not as an absence, but as a gesture”.

Ken Wilder, Pendulum, 2025 in Beyond the Visual at Henry Moore Institute 28 November 2025 – 19 April 2026. Photo: Joanne Crawford.

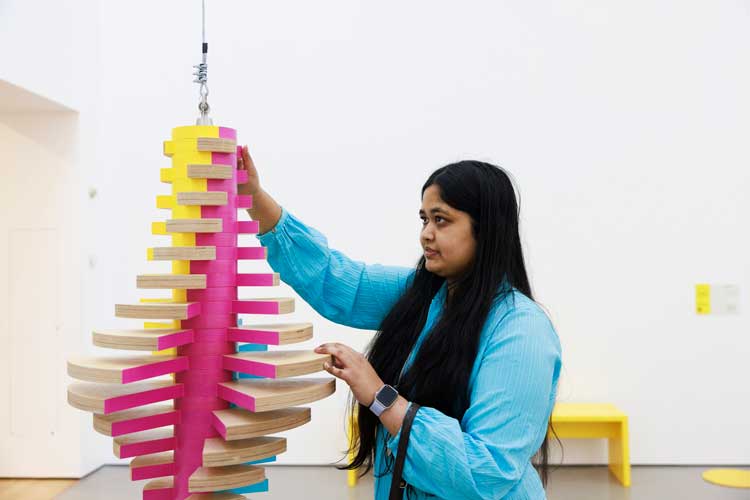

Slightly more playfully, co-curator Ken Wilder’s Pendulum (2025) speaks to the seeing visitor, giving them further insight and food for thought. The piece, built like a child’s wooden stacking toy, with alternating plywood rings and cogs, wide at the centre and narrow top and bottom, is painted in cyan, magenta and yellow. When spun rapidly, the colour appears as grey due to colour mixing resulting from limitations of vision when perceiving rapidly rotating objects. A film playing alongside explains the colour science behind this phenomenon.

Two visitors and a Guide Dog with an Information Assistant interacting with Henry Moore's Mother and Child: Arch, 1959 in Beyond the Visual at Henry Moore Institute 28 November 2025 – 19 April 2026. Photo: Joanne Crawford.

The two historic works in the show are Barry Flanagan’s Elephant (1981) and Moore’s Mother and Child: Arch (1959, cast 1967), both of which it feels a real privilege to be allowed to touch (not that it is any less of a privilege to touch any of the other artists’ works, of course). Perhaps closest to Moore’s in a sense are Lucia Beijlsmit’s four Windows. Made from leftover fragments of marble and sandstone from quarries, Beijlsmit’s pieces have been left roughly hewn on their outsides, but polished smooth on their insides (another nod to Johnson’s notion of inhibition, perhaps). “It’s also like my point of view that the inside is more important than the outside, not only in sculpture, but also in the persons,” the artist says. In the centre of each block, she has made a “window”, through which one can view the exhibition as if through a different lens. The feel of the stones is also quite wonderful, both in terms of roughness and smoothness, as well as temperature.

-(c)-Rob-Harris-(20)-.jpg)

Lenka Clayton, in collaboration with The Fabric Workshop and Museum, Philadelphia, Sculpture for the Blind, by the Blind, 2017 in Beyond the Visual at Henry Moore Institute 28 November 2025 – 19 April 2026. Courtesy of the artist and Catharine Clark Gallery, San Francisco. Photo: Rob Harris.

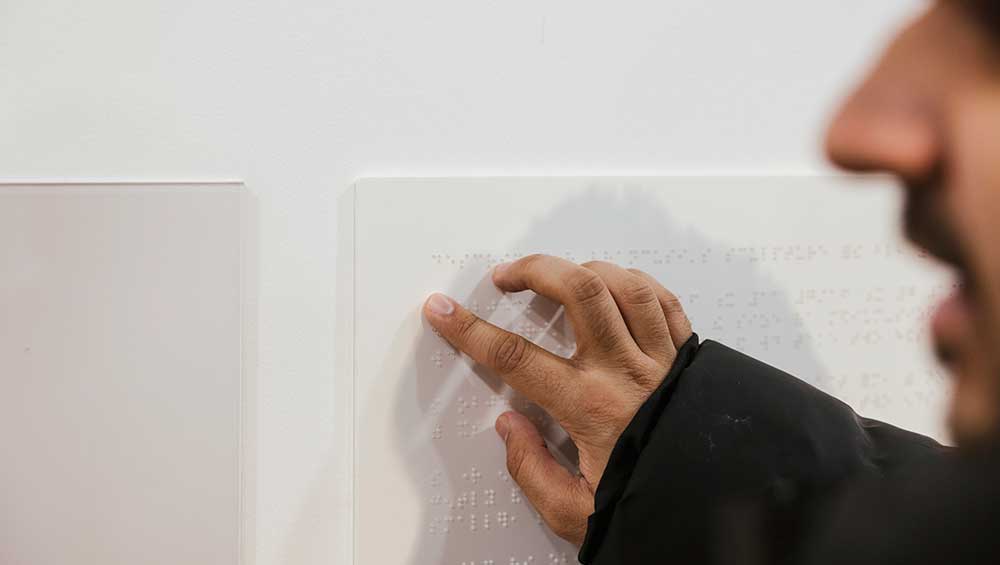

The work that really sums up the project, though, is Lenka Clayton’s Sculpture for the Blind, by the Blind (2017). The starting point for this piece was a sculpture by Constantin Brâncuși called Sculpture for the Blind. As Clayton explains: “I came across this sculpture … in the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. And I’m a sighted person. I could see the sculpture, and I could see that it was in this big glass case. And when I heard the title, there was something extraordinary that it suggested to me that it was a sculpture titled for the blind, but it was displayed permanently in a way that it was completely inaccessible to anybody who would identify as blind.” She found this “confused logic” both “thrilling and fascinating and ridiculous” as well as “very demonstrative of the human condition”. Having tried and failed to get the Philadelphia Museum to loan the artwork, to allow it to be scanned to make a copy, or to allow it to be touched, Clayton wrote a description of the work and read it out in a workshop for blind and visually impaired people, who then made a sculptural form of what they understood. These waxed plaster pieces – completely unboxed and free to be touched – are what are on display here, along with a photograph of the Brâncuși and a Braille transcript of Clayton’s description – something this time able to be experienced only by blind and partially sighted people who have learned the script.

As Wilder reiterates: “This is not an exhibition of sculpture for the blind. We made that very clear at the very beginning. It’s for everybody. The idea of sculpture for the blind is a bit odd, because it suggests it’s a special type of sculpture that is somehow for the blind, and all other sculpture isn’t. We wanted to question that. The whole point of the project, the whole point of the research, is turning that assumption on its head and asking: how do we think about sculpture?”

As for whether you’ll be allowed to touch objects in forthcoming exhibitions at the Henry Moore Institute – well, maybe not. But lessons from this project have certainly been taken on board. The funding from the Arts and Humanities Research Council allowed for extensive training for the front-of-house team on being sighted guides and doing live audio description, and this, as well as pre-recorded audio descriptions are now in place and will continue. Wilder concludes: “It’s fantastic we’ve got this exhibition, but the aim was that this would be an exemplar that other institutions could take on board. The aim was not just the one-off exhibition. We’re hoping this will have a global impact.”

References

1. In 1968 the photographer John Hedgecoe visited Henry Moore and his wife, Irina, at their home. They recorded a series of conversations about Moore’s life and work.

2. Blind aesthetics: complexity, contingency and conflict by David Johnson in Beyond the Visual: Multisensory modes of beholding art, edited by Ken Wilder and Aaron McPeake, UCL Press, 2025, pages 357-72, page 357.