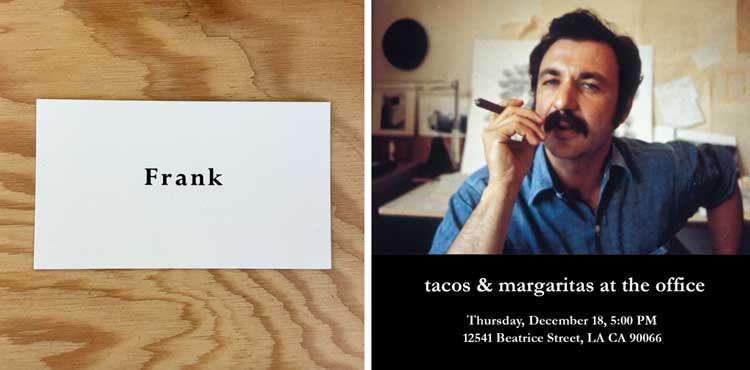

Frank Gehry sitting in one of his Little Beaver cardboard armchairs, with art dealer and curator Jeffrey Deitch. Photo: Ann Philbin.

by JILL SPALDING

AHH, FRANK.

So, to a person, did the 90 or so of us convoked to his studio to celebrate and mourn him bid farewell to a giant, an icon, our friend. Frank’s beloved wife, Berta, stood at the entrance, encircled by those he had affected, from the draughtsmen to Harrison Ford.

Projected on to the concrete wall, the image of pre-celebrity Gehry – tousled dark hair and moustache – summoned up memories shared with whoever stood near. John Walsh, former longtime director of the Getty Museum, remembered a visit with Frank and Berta to the Mauritshuis in The Hague where they spent an inordinate time comparing Vermeer to De Hooch. Society photographer Joan Quinn reminisced about family dinners with them at their neighbourhood Chinese eatery, Madame Wu’s Garden. Katie Anawalt recalled the day she proposed to the artist Chuck Arnoldi and he said, “Wait right here”, raced off to ask Frank what to do; and told, “She’s great, marry her!”, accepted. Chuck chimed in with their day on the 74ft Foggy – named for Frank’s initials, FOG, as is his studio, it’s the only bespoke sailing boat he ever designed – when, to the delight of MS NOW’s lead anchorman, Lawrence O’Donnell, he was encouraged to take the wheel, saw that the entire helm, like the deck, was an artwork, and panicked.

My own memories spilled into the night, the drive home and the day following. The first time I heard of Frank was in 1978, via a peculiar house, built in Santa Monica by some renegade young architect, that was breaking the rules and offending the neighbours. Perfect for my magazine I thought, on driving past it and almost crashing the car, so bizarre were the soon-to-be-signature elements of chainlink fencing, plywood, angled glass, exposed framing and corrugated metal designed to partially hide, but not replace, the original pink adobe Dutch colonial bungalow. Perhaps because I hadn’t conveyed (having not yet understood) the full enormity of Frank’s achievement – architecture as sculpture, curved space as landscape, skewed angles as music – Vogue’s great Leo Lerman thought otherwise. “Frank who? G-e-a-r-y?” Given that Frank’s only other known house was diminutive (for Ron Davis, a riff on the artist’s shaped canvases), US Vogue passed. But UK Vogue didn’t, and that’s how I inadvertently gave Frank his first international exposure and earned his undying loyalty.

Frank loved that I championed in print his remodel of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, that had sent the old guard into shock. That I had introduced him to Si Newhouse, who subsequently commissioned the Condé Nast cafeteria that constituted Frank’s first New York commission. That I cheered him on at the Sun Valley ice hockey matches he showed up for and with no practice – still the Toronto boy– aced. That I immediately understood the importance of his piscine moment – when he picked up some shards outside a Formica factory he was visiting and played them into fish scales, most notably constructing a monumental undulating sculpture for the fated Peter Lewis house, which then ended up in a sale I was manning for the Music Center, and later a series of standing lamps. I bought one immediately, owned it for three months then realised that the $6,000 I had paid for it was the exact sum of my son’s fall school tuition and abjectly returned it to the gallerist Fred Hoffman, who promptly resold it to the art collector and Museum of Modern Art president Agnes Gund. Frank stepped in with the gift of his Little Beaver cardboard armchair, which still holds pride of place in my home, though only he has since sat in it.

Not that devotion spared me his famed ire when crossed. On the opening night of Frank’s groundbreaking Walt Disney Concert Hall, in order to judge the acoustics I had asked to be seated in the Gods and, on rising at intermission, almost keeled over, so low was the railing. Finding Frank in the lobby, I raved on about the hall and the sound, then reported my vertigo and suggested he raise the railing. He didn’t speak to me for a year.

There was the time that Frank, Berta, the film-maker Sydney Pollack and I had been piped by a crew of 22, including the chef and trainer, on to the Lone Ranger, the 255ft tugboat that Peter Lewis, of Progressive Insurance, with helicopters, pool and a basketball court, had converted into a pleasure yacht, and was now sailing up Norway’s largest fjord. Upon passing mountains relating so closely to Frank’s curved facades as to, I was certain, enchant him, I raced below deck to his cabin and banged on the door to ask that he come view them, only to anger him into ignoring me for the rest of the day because I’d interrupted his massage.

A back story of interest here: on our third night out, after a touching ceremony hanging over the railing as Frank and Berta dropped candles fixed to white paper plates in the coal-black ocean to mark the passing of I’ve forgotten who, as we sat around the dinner table – Peter gently high on weed – Frank asked for a final yes or no to the funding for New York’s long-projected downtown Guggenheim. “Yes,” Peter assured him, but conditional on the museum’s then director, Tom Krens, having found a way to fund the other half. “Has he?” Frank persisted. “Well, let’s find out,” answered Peter, and 12 hours later, halfway up the fjord, Krens was dropped by helicopter on to the deck.

His brilliant idea, we learned at dinner that night, was to sell all the museum’s famed Kandinskys. When that didn’t fly, Krens proposed to sell everything else and, after securing the downtown building, using the rest of the profit to acquire one great contemporary work yearly. Frank looked at Peter, Peter looked at Frank, and Berta and I knew it was over. Krens was hoisted up and out in the morning and the next I heard of him he had invited the Marchesa Katrin Theodoli to lunch to discuss stretching her famous fastest-of-its-class Magnum to 190 feet to accommodate enough art to establish a floating, world-touring Guggenheim.

Police guarding the entrance to the Guggenheim Bilbao before its opening in October 1997. Photo: Jill Spalding.

Our most dramatic shared experience was at the VIP pre-opening of Bilbao, the billowing museum already held to be the now star-architect’s masterpiece, that had been conjured from the ideas developed for the unrealised Peter Lewis house. I showed up early so as to elicit a few quotes from Frank for my article, to find him standing out front with a policeman, watching Jeff Koons and his assistant still planting the welcoming Puppy. A white van drew up, with what the artist thought were more florals but the men who stepped out were ETA terrorists carrying machine guns. Koons grabbed his assistant and ran to the nearby cafe, Frank and I behind them, the policeman was shot dead, police cars screamed in, removed the body, threw up barriers, and the next thing I remember was the museum doors opening as though nothing had happened, Frank besieged by reporters and collectors. If I hadn’t taken pictures of this surreal scenario and the bunches of flowers already piling up where the policeman had fallen, I wouldn’t have credited any of it.

It’s telling that dramatics didn’t eclipse the quotidian; the night Frank and Berta came for dinner with their teenage sons, Alejandro and Sam, whose cursing in front of my boys occasioned the apology of a case of Champagne; the day that Frank and Maggie Keswick (the great landscape designer and daughter of the last Taipan) shared her plan for a red river to flow past the Lewis house.

As we filtered out into the night, to a person all looked up once more at our friend’s tousled image. Ahh, Frank, no one shall ever again ask how to spell your name. You belong to the world.

• Frank Owen Gehry, architect, born 28 February 1929; died 5 December 2025.