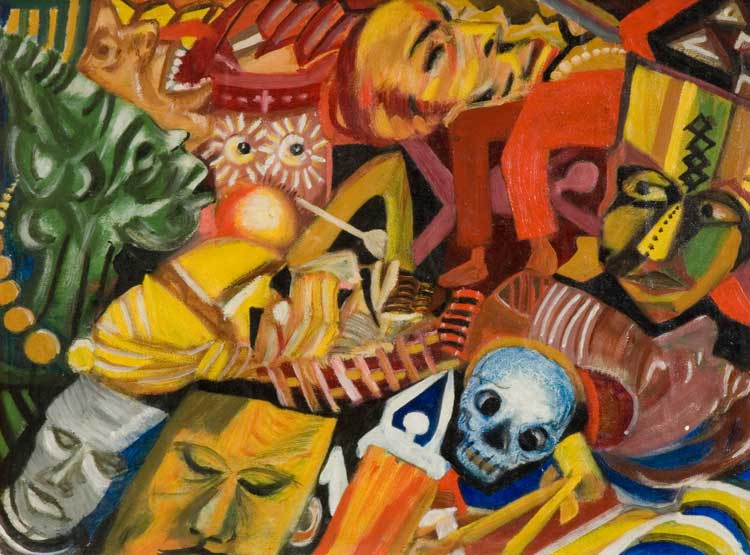

Uzo Egonu, Will Knowledge Safeguard Freedom 2 1985. © Estate of Uzo Egonu. Tiana and Vikram Chellaram.

Tate Modern, London

8 October 2025 – 10 May 2026

by JOE LLOYD

Nigeria is already one of the world’s most populous countries and is set to become even crowded. Nigerian Modernism, the Tate Modern’s survey of the country’s mid-20th-century artistic explosion, might be one of the world’s most populated exhibitions. Bankside’s exhibition rooms are stuffed to the gills with paintings, sculpture, prints, ceramics and wooden objects, to the point where it is easy to be overwhelmed. Some rooms are dedicated to individual artists, others to schools. Many works have no space to breathe. The Tate deserves praise for bringing Nigerian art to a wide attention, and for trying to pursue as many avenues as possible. But for those uninitiated in the country’s myriad artistic traditions, the exhibition might feel like being thrown into the deep end before learning how to swim.

This could be a natural side-effect of Nigeria’s complicated history. For centuries, it was a series of discreet kingdoms inhabited by diverse ethnic groups, the largest of which today are the Hausa, Yoruba, Igbo and Fulani. British colonisation spent decades exploiting it through local proxy rulers before sewing it together as a single unified territory in 1914. It gained full independence in 1960, abolishing the British monarchy to become a republic three years later. A succession of coups, civil wars and military dictatorships followed, before it became an uneasy democracy. Although the title Nigerian Modernism might imply that the exhibition covers the Nigerian parallel to the early 20th-century artistic movement, the bulk of the works on display come from the period just before and after the birth of the independent state.

Justus D. Akeredolu, Thorn Carving c1930s. © Justus D. Akeredolu. Research and Cultural Collections, University of Birmingham.

There are some exceptions, such as the c1900 portrait photographs of Jonathan Adagogo Green and the exquisite miniature 1930s thorn carvings of Justus D Akeredolu. Although the British erased many of the systems and rituals of indigenous life, they did not stamp out the art and craft techniques. One of the most striking early works in the exhibition is a pair of wooden door panels (c1910-14) by the Yoruba sculptor Olowe of Ise, which were later exhibited in the 1924 British Empire Exhibition in London. The works depicts a king receiving Captain Ambrose, a British officer, surrounded by wives, courtiers and prisoners carrying the captain’s belongings. Ambrose cuts a poor figure compared with the dignified ruler. Olowe’s carving has a palpable tactility through lines and indentations, and a liveliness through his use of coloured paint. Elsewhere in the same room, the paintings of Aina Onabolu – who trained in London and Paris and later set colonial Nigeria’s official painting curriculum – are executed in a conventional European style.

Aina Onabolu, Portrait of an African Man 1955. © Aina Onabolu. Yemisi Shyllon Museum of Art, Pan-Atlantic University.

-1962.jpg)

Ben Enwonwu, The Dancer (Agbogho Mmuo - Maiden Spirit Mask) 1962. © Ben Enwonwu Foundation, courtesy Ben Uri Gallery & Museum.

A shift comes with the first artist the exhibition spotlights, the sculptor and painter Ben Enwonwu. By the time of independence, he was the most internationally successful Nigerian, or perhaps even African, artist of his generation, winning acclaim for works such as a conservative 1957 statue of Queen Elizabeth II. His work was warmly received by the British public. In 1960, he was commissioned by the Daily Mirror to create sculptures for its now-demolished headquarters at Holborn Circus. He responded with an uncompromising series of seven carved ebony figures based on traditional Igbo sculpture, five of them holding up a newspaper as if it were a sacred text or a winged being about to take flight. They vanished a few years after being installed, before being discovered in 2013 in a school garage in Bethnal Green, east London; rumours persist that they had been stolen by the East End gangsters the Kray Twins.

Uche Okeke, Fantasy and Masks c1960. © The Prof Uche Okeke Legacy Limited and Asele Institute Ltd. Photo courtesy of Research and Cultural Collections University of Birmingham.

Enwonwu saw himself primarily as a sculptor, but it is his paintings that seem more overtly modern. He painted ritual dancers in masks and feathered headdresses, teeming durbars and dense thickets of local vegetation. There are echoes of Degas, Cézanne and Picasso, though Enwonwu’s work remains entirely its own, even aside from its locally specific subject matter. At the Tate, it ushers in a phalanx of painters who merged indigenous and European influences to create their own individual modes. The Zaria Art Society, founded in 1958, sought a “natural synthesis” that would allow them to express a new African identity. Uche Okeke’s The Conflict (After Achebe) (1965) adapts a scene from Chinua Achebe’s novel Things Fall Apart (1958), in which a Christian convert’s home is burnt down after he unmasks a ritual dancer. Okeke paints in the intense yet melancholy colours of Kirchner or Munch.

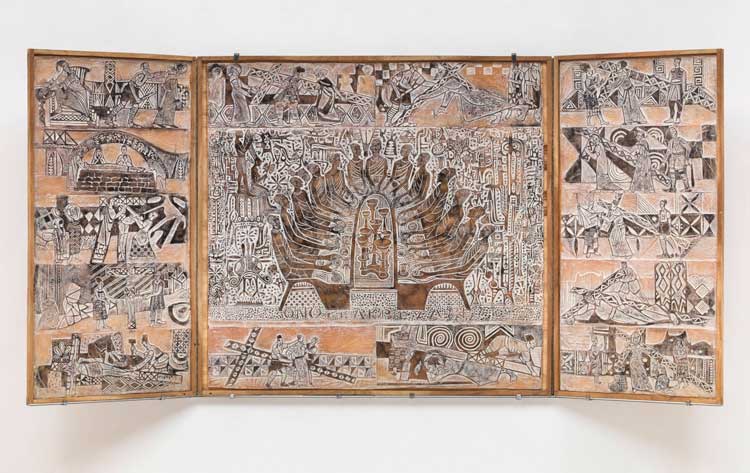

Bruce Onobrakpeya, The Last Supper 1981. © reserved. Tate Collection.

Many of the paintings take a somewhat fantastical turn, drawing on nature and myth. Okeke’s Primeval Beast (1961) is a monstrous toad with sharp teeth, while Bruce Onobrakpeya imagines Négritude (1960) – named for the anti-colonial movement in Francophone sub-Saharan Africa – as a bizarre chicken-like bird. We meet faceless villagers, human-faced trees, hordes of demons and deities. There are also closely observed scenes of life, but many feel muted – even fusty – against their more imaginative competition. Of the dozens of painters featured in the exhibition’s central sections, Demas Nwoko stands out with his soft-toned style. His Nightclub in Dakar (1963) captures three couples dancing under coloured lights – an entirely different sort of movement from the dance-based rituals charted by Enwonwu. It is one of the few works in the show that captures something of the urbanisation of post-colonial Africa, albeit in a different country.

-1974,-printed-2012.jpg)

JD ’Okhai Ojeikere, Untitled (Mkpuk Eba) 1974, printed 2012. © reserved. Tate.

A room devoted to urban life in Lagos follows, with a selection of high-life records, representations of some of the architectural marvels of the 1960s and JD ’Okhai Ojeikere’s photographs of sculptural hairstyles. This section feels somewhat meagre compared with the paintings that come before and after. We are told that Lagos was a rapidly growing and changing metropole, but the exhibition does not convey much of the excitement of the moment. The creative ferment in and around Lagos that gave rise to Fela Kuti and the Afrobeat genre, arguably one of the most thrilling in musical history, is conscious by its absence.

Uzo Egonu, Stateless People an artist with beret 1981. © The estate of Uzo Egonu. Private Collection.

Instead, the exhibition takes us back towards tradition, with the intoxicating output of the Oshogbo School. There are mind-bending embroideries that make the excesses of western psychedelia seem muted, and creative drawings of Yoruba mythology. When we meet urban life again, it is in Uzo Egonu’s eloquent 1981 paintings of Stateless People, vibrantly coloured yet deeply downbeat depictions of Africans exiled from their homeland, painted when Egonu’s vision was impaired by cataracts. Placed at the end of the exhibition, it seems to suggest that modernity has failed Nigeria. And while that may be the case, I wish the exhibition had given a clearer vision of what modernity in Nigeria felt like in the moment.