Sammy Baloji, Salzburg International Summer Academy of Fine Arts. Photo: Mira Turba

by KRISTIAN VISTRUP MADSEN

Lubumbashi is a place where first you have mining activity and then you have people. This is how Sammy Baloji (b1978) describes his place of birth in what was then the Katanga province of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The artist, who has lived in Brussels since 2010, takes the landscape and its resources as his starting point in his interrogation of the continued impact of colonialism and the fraught relationship between humans and the land that we inhabit.

Baloji’s work often begins in colonial archives, where he finds old photographs to superimpose on to his own. In Tales of the Copper Cross Garden, a film he made for Documenta 14 in 2017, footage of the massive machinery used in the copper industry is soundtracked by choirboys as part of a reflection on the role of the church in the colonial enterprise. Through the lens of mineral extraction, we see timelines and geographies collapsing. Across shifting political regimes, from colonial occupation to dictatorship and the more recent rule of various national and transnational mining companies, Baloji shows that beauty, conflict and complexity are constant and concomitant.

The Salzburg Summer Academy is the oldest of its kind in Europe. It has welcomed art students and professionals to the Hohensalzburg Fortress every year since 1953. This year, Baloji was teaching a course called Hunting and Collecting, with the writer and curator Lotte Arndt. Salzburg is all Sound of Music and Edelweiss. As one of the academy’s students put it, this is a place where they have not realised that, in context, ugly things can be beautiful, too.

Sammy Baloji, Extractive Landscapes, installation view, Salzburg International Summer Academy of Fine Arts 2019. Photo: Christian Ecker.

Crowning the city from a hilltop, the 11th-century fortress is the epicentre of Salzburg’s immense tourism industry. At this unreal location, where dramatic clouds rush down from the Alps and hordes of visitors juggle cameras and Mozartkugeln, I meet Baloji for a few beers. We talk about the course he is giving with Arndt and his exhibition, Extractive Landscapes at the Stadtgalerie Museumspavillon. Both take up themes relating to the extraction of natural resources by transnational industries, colonialism and colonial collections. The gallery is on the other side of the Salzach River in the equally fairytale-like Mirabellgarten, a baroque complex of highly pruned flowerbeds, crowded with statues and fountains. A far cry, I suggest, from the vast and conflict-ridden Congolese landscapes portrayed in the exhibition. But, it turns out, maybe it is not.

Kristian Vistrup Madsen: How does an exhibition like yours sit in a place like this?

Sammy Baloji: The invitation from the Stadtgalerie came after the invitation to teach here, so the exhibition also came out of my collaboration with Lotte [Arndt]. I’ve never been here before, and I didn’t know exactly how to relate to this place. How can this work make sense here? Lotte and I were talking and, after looking at the history of Salzburg, we started researching the salt mining activity that’s been going on here: Salzburg was actually built around salt mining. For us, it became interesting to make an exhibition here that can talk about the landscape and bring out some of its complexities. It was quite interesting to consider these ideas, and see how landscapes are controlled, and the subjects of conflict – to show the other face of history, in a way.

Sammy Baloji, Extractive Landscapes (detail), installation view, Salzburg International Summer Academy of Fine Arts 2019. Photo: Christian Ecker.

KVM: The course you and Lotte have run here in Salzburg, Hunting and Collecting, has focused on landscapes and museum collections as bearers of history in postcolonial contexts. How did this collaboration come about?

SB: It began with an exhibition of mine that Lotte curated in 2015. It was at Mu.ZEE, the Museum for Modern Belgian Art in Ostend, and it was from this exhibition that we took the title for the course: Hunting and Collecting. So, it’s a project we’ve been doing for some years. It started from a colonial photo album I got from a collector. The photos are from the early 20th century, and belonged to Henri Pauwels, a Belgian commander in the Congo. Pauwels was commissioned by the Africa Museum, an ethnographic museum in Tervuren, Belgium, to hunt different types of animals in the east of Congo, which would be used to create dioramas in the museum. But the album also functions as documentation of Congo at the time. It shows lots of scenes where he’s posing in front of killed animals – gorillas, leopards, lions – but there are also photographs of landscapes and places, and of the different tribes he encountered. So, it’s really a colonial album.

I knew there were a lot of conflicts going on in that area, so when I discovered the album I got the idea to revisit the same places today. In the eastern parts of the country, there are a lot of conflicts over the land because most of the people there were dispossessed by the national park that was imposed by the colonial regime. And during the genocide in Rwanda in 1994, the park also became a place where soldiers would flee to, living inside and around the park, always being chased by the government from Rwanda. And on top of all these conflicts of borders, there’s also another thing: the discovery of coltan, a mineral used for computers and smartphones.

KVM: So there is a conflict over the land as territory, but also over the resources?

SB: There are companies that are interested in buying, but they are not extracting from the land directly. It’s the local people, or local groups of soldiers, who own the land, and are digging in an artisanal way, and selling the mineral resources to companies in China, or elsewhere. It’s more problematic and complex than just foreign companies coming in. It’s been going on for more than 15 years now in the background of various ethnic conflicts.

My idea was to travel in that area with the album and revisit the places, so I started working with a local photographer who’s also a fixer for international journalists. He’s native to the area, and knows very well the complexity of the situation. I started working with him, but also looking at his pictures, and bringing them into the album, making collages. In that way, the album provides a colonial context to show us how the conflicts still going on today were shaped. It allows us to look at historical and current dispossession through the gaze of mineral resources and the conflicts over the land.

Sammy Baloji, Extractive Landscapes, installation view, Salzburg International Summer Academy of Fine Arts 2019. Photo: Christian Ecker.

Another thing I discovered while travelling in the provinces was the presence of more than 500 NGOs working at the same time. Why should there be 500 NGOs working at the same time, trying to solve the same problems? This is a whole other business that is going on.

KVM: It sounds as if there is a kind of NGO industrial complex?

SB: I would say so, but there are also local NGOs that have been established with the expectation of being supported by the international foundations – it’s a weird situation.

KVM: Starting from the colonial album, it was obvious for you to also work with photography. But it is also interesting that Pauwels was hunting animals for dioramas …

SB: Precisely. I was very interested in the diorama itself as a format that is used in museums. It started with the first taxidermies at the Museum of Natural History in New York. Already in the 1920s, Carl Akeley went to Congo hunting for different types of gorillas, which would go into the first dioramas. It was a huge success. After that, the Belgians also wanted their own dioramas, and that’s why they sent Henri Pauwels, who did the album. I wanted to connect these international influences from New York and from London. In a way, this relates to how mineral resources travel all over the world, and how this creates a particular power dynamic between the global north and global south. For instance, the minerals that were used in the first atomic bomb in the US actually came from Congo. I’m interested in the fact that uranium travels from Central Africa to the US and then lands on Hiroshima.

KVM: What a striking fact! Then, similarly, gorillas from Congo to New York, creating a fashion for dioramas in Belgium … It tells us so much about the link between the colonialism of the past and what we call globalisation today.

SB: I’m always looking at how things travel on a global level. Akeley’s dioramas are still on display in New York. The background is a painting, and I went to the same region and took a picture, but, in mine, you can see that people are living there in camps organised by NGOs.

Sammy Baloji, Extractive Landscapes, installation view, Salzburg International Summer Academy of Fine Arts 2019. Photo: Christian Ecker.

KVM: Is it a refugee camp?

SB: It is. Among the people in the photograph, you have the soldiers fighting in the region, you see them carrying mobile phones. Since this is the area where they are extracting metals, they almost function like advertisements for extraction in Congo. I’m interested in how these things become entangled not only on a local level, but on an international one.

KVM: And how you can capture that in a single image. From seeing your exhibition at the Stadtgalerie, I would say there are two seemingly contradictory movements happening in your work. On the one hand, it is about making things visible, these processes of extraction and colonialism, about tracing materials, and showing how their production is sociopolitically situated. On the other hand, it is about making things abstract, hiding them or showing them in fragments. For instance, you show a series of maps, but they are cropped in different ways to leave out the information or the context that would allow us to read them.

SB: Yes, in doing this, I’m reproducing the colonial process, which is also about strategically erasing or hiding information, producing an abstract relationship to reality. With maps, for example, it’s always a question of what’s reality and what’s an abstraction. If you’re looking at a landscape, but you don’t have all the information, the captions, how do you read it?

KVM: In a way, maps shape our understanding of reality, but they are also just images.

SB: You can see that in the film, too. There is a precolonial traditional knowledge of the land, which is represented by the chief who says: this is the border – but it’s only in his mind. It’s not the “real” border because the land is already occupied by others. So you have these two understandings of the land, or sets of knowledge, which are in confrontation with one another. On both sides, the other’s knowledge becomes abstract, and there is a real tension in between.

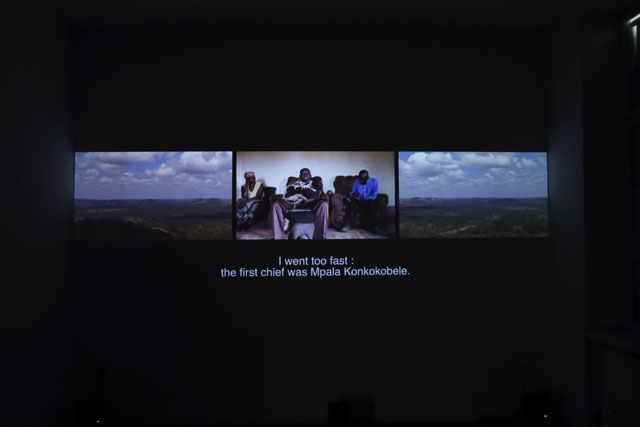

Sammy Baloji, Extractive Landscapes, Salzburg International Summer Academy of Fine Arts 2019. Photo: Mira Turba.

KVM: There is a nice line in that film that I picked up on. A young man says to his father, who is the chief: “There are many stories, do you want to add another one?” He has been telling stories throughout the film, listing the lineage of chiefs and the conflicts they have had over the land. It is so clear in that line that history is about storytelling, and that there are many different ones to tell. You are interested in this slightly fictional aspect of history?

SB: Absolutely. Going to school in Lubumbashi, we never learned about colonialism. After we gained independence [from Belgium] in 1960, several conflicts erupted. It was also the period of the cold war, and because Congo was important in terms of mineral resources and uranium, the US didn’t want it to be on the Soviet side. So for 32 years, from 1965 until 1997, we had a dictatorial regime led by Mobutu Sese Seko who was protected by, and working for, the CIA. Mobuto tried to promote pride in being Congolese, to come back to authenticity and the precolonial times. But actually he was a dictatorial imposition, who used traditional clothing – he wore a hat made out of leopard skin – as a kind of distraction from talking about the colonial system itself. That was not part of what we were learning at school. That history was erased, in a way, for a time.

From 2002 to 2004, I was working as a documentary photographer on a project about colonial architecture. I was working with an architect and a historian to document the colonial architecture and industrial heritage. It was only then that I came to archives of the colonial period, and started to discover the history, through understanding the way the city was built. For me, it became part of how society creates a kind of amnesia in order to continue; how we produce a new identity while hiding part of another one that was there before. But where’s the critique? Where’s the aspect of analysis that shows us how the past and the present are linked?

When I started doing research at this ethnographic museum in Tervuren, I came to the realisation that even in Belgium they’re not talking about the colonial period. Or, if they are, it’s in another way – they have another version of the colonial history. There was a lot of propaganda during the colonial period – this idea of bringing education and civilisation and Christianity to savages – so on both sides, there’s a lot of storytelling.

KVM: How has living in Belgium changed your perspective on colonialism?

SB: I’m not interested in colonialism as nostalgia, or in it as a thing of the past, but in the continuation of that system. My work is really about what is going on now. We always talk about how Germany or England had colonies, and about how they would relate as states to the countries they were colonising. But it’s not about them. In colonialism, you can also find the beginning of capitalism itself. One of the reasons why King Leopold took Congo was to create a place for free trade. Investors were coming from everywhere. At a certain point, it was treated as imperialism, but it’s also capitalism and it’s still going on now. Everything is the same, it just changed names, and I’m just linking up these stories.

KVM: In the exhibition, you show these military remnants, bombshells produced in Congo, which were used in the world wars, but are now popularly used for potted plants in Belgium. As objects in the room, they are very beautiful, very decorative.

SB: With those bombshells I want to revisit the first and second world wars. I’ve been living in Belgium since 2010, but I’ve never seen an exhibition about those wars that mention the involvement of Africa, or the consequences of the wars in Africa. The first world war was a revision of the colonial system, because things changed after that. Germany owned Cameroon, Rwanda, Burundi, Namibia. But after the war, England, Belgium and France divided those places between them. And during the world wars, a lot of workers were made to produce more copper to make bombs. Even outside of that, African soldiers fell in Tanzania and in Rwanda. So the war was everywhere, and was waged with colonial interests. Still, it’s always seen from just one perspective. So, while in Brussels, I’ve been bringing together stories that people have tended to separate. Again, the second world war ends with an atomic bomb, and the uranium came from Congo.

KVM: You find visual and material traces of these histories, like the bombshell plant pots, and bring them together to show how they are connected, and also how the past extends into the present.

SB: Yes. Another example: the plants in the exhibition are ordinary houseplants, which you can find in botanical gardens everywhere in Europe, but they are also plants that grow naturally in mining areas in Katanga. Plants, like minerals, are always travelling, but when it comes to the migration of people, there are borders and walls.