,-c1896,-designed-by-John-Henry-Dearle,-embroidery-overseen-by-May-Morris-photo-by-Anna-McNay.jpg)

Vine screen panel embroidery (detail), c1896, designed by John Henry Dearle, embroidery overseen by May Morris, c1896. © William Morris Society. Photo: Anna McNay.

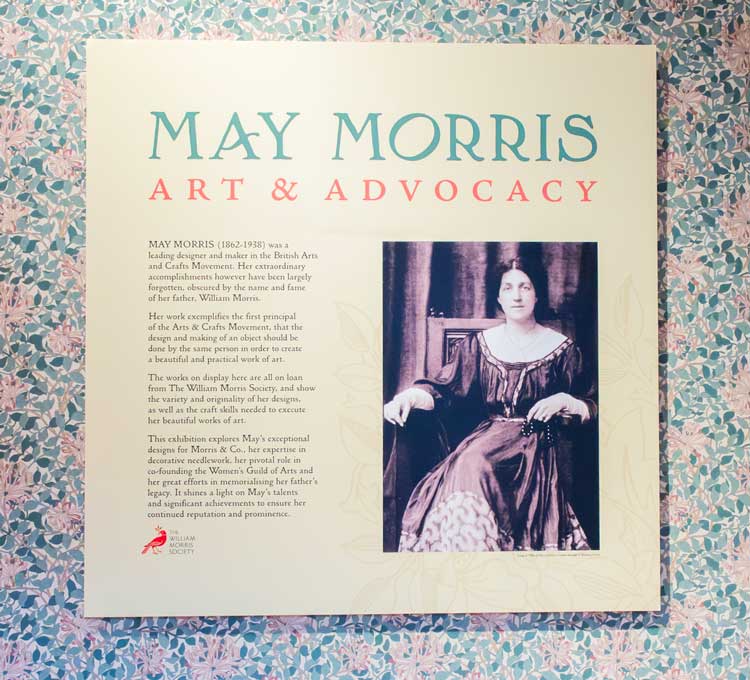

Russell-Cotes Art Gallery & Museum, Bournemouth

5 April – 5 October 2025

by ANNA McNAY

May Morris’s obituary in the Times described her simply as “daughter of William Morris, the poet”, but she was so much more. Born Mary “May” Morris in 1862, she was the youngest daughter of William and his wife Jane (née Burden, lover and muse of Dante Gabriel Rossetti). Her upbringing was unconventional and bohemian. William and Rossetti – together with other friends – launched their business, later Morris & Co, at about the time of May’s birth, and she and her sister, Jenny, grew up surrounded by craftwork. They were home educated, and while Jane and their aunt worked on embroidery in the home studio, the children frequently stitched simple items such as pen-wipers and kettle-holders. May’s father also taught her to draw (and one of her sketchbooks is included in a vitrine in this exhibition). Her whole childhood was essentially an apprenticeship.

In 1878, aged 16, Morris enrolled at the National Art Training School (now the Royal College of Art), where she studied embroidery, looking especially at medieval forms. After her studies, she unsurprisingly worked at Morris & Co. By dedicating herself to the promotion and preservation of the family (AKA her father’s) legacy, May ended up being all but erased herself. In 2017, the William Morris Gallery in Walthamstow put on the exhibition May Morris: Art & Life, the most comprehensive survey of May’s work to date, which brought together more than 80 works from collections around the UK, and was crowd-funded through an Art Fund Art Happens campaign. This exhibition in the simply fabulous and very apt setting of Bournemouth’s Russell-Cotes Art Gallery & Museum is smaller and focuses on Morris’s wallpaper designs and decorative needlework with works on loan from the William Morris Society.

At the time of the William Morris Gallery exhibition, its then curator, Anna Mason, said: “About 30 years ago, Jan Marsh published a biography of May, and there was a small show of her work at the William Morris Gallery in 1989, but since then there’s been a huge vacuum … She is top of the list of research enquiries we get, there have been new artists responding to her work and lots of people asking questions about her life and career.” And with this interest only having increased in the interim, this exhibition in Dorset is timely.

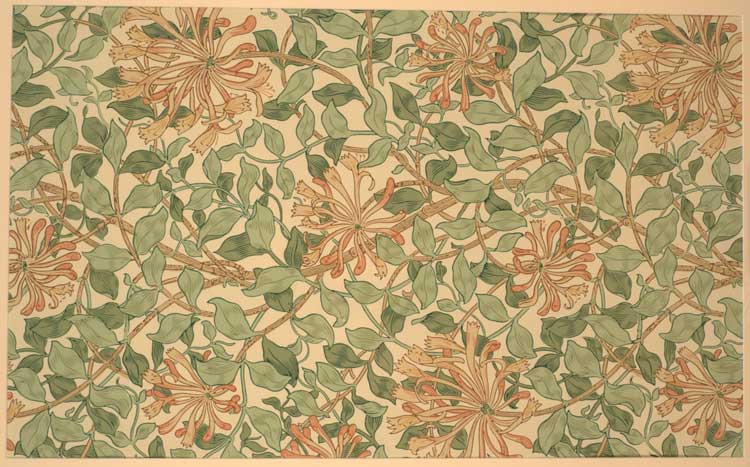

Honeysuckle, designed by May Morris, manufactured by Jeffrey & Co for Morris & Co, c1883. Blockprinted in distemper colour. © The William Morris Gallery, London Borough of Waltham Forest.

The first room opens with a section on the three wallpapers Morris designed between 1881 and 1886: Honeysuckle (c1883), Horn Poppy (c1885) and Arcadia (c1886). While they were well received and remain popular to this day – especially Honeysuckle – these were to be the only three she created; William, by comparison, designed 41 wall- and five ceiling papers. A couple of his wallpaper designs are included here as well, enabling interesting comparison. May shows a general preference for lighter tones and hedgerow and meadow plants, frequently based on her own botanical drawings, whereas William tends towards more richly coloured fruits and elaborate acanthus leaves. Nevertheless, it is clear that both were conforming to the house style of Morris & Co, making it easy to see how misattribution was possible. (Many of May’s works were indeed misattributed to William.)

Design for Honeysuckle, c1883. Pencil and watercolour on paper, 99.6 x 68.6 cm. © William Morris Society, bequeathed by Helena Stephenson, 1970.

Most of the company’s designs were not coloured in during the design process, leaving the choice of colours to the last phase of production. Many designs would carry notes of the colours to use, allowing for them to be changed or swapped. Horn Poppy, for example, which features open and closed flowers and foliage against a pin-dotted background, was offered in 10 different colourways. Despite its detail, it only required three woodblocks (by comparison with the 11 required for William Morris’s Jasmine, 1872). To help visitors visualise the process a little better, the exhibition also presents a beautifully carved woodblock used to print Honeysuckle.

Arcadia wallpaper, c1886, designed by May Morris, colour woodblock print on paper, manufactured by Jeffrey & Co for Morris & Co. © V&A, given by Morris & Co. Photo: Anna McNay.

The reason Morris designed just three wallpapers was that, in 1885, she took over the management of the company’s embroidery department. The role involved liaising with clients, overseeing textile design and production, pricing and invoicing products, and recruiting and training employees. In the 1891 census, Morris described herself as “artist, designer and embroiderer” and ticked the “employer” box, emphasising how seriously she took her role. “Design is the very soul and essence of beautiful embroidery,” she said a couple of years later.

An interesting example of design is that for Flowerpot (c1885-90), which demonstrates May’s merging of two designs – one her father’s elaborately swirling drawing, one her own sparser and more delicate yet bright watercolour – into a new one. Elsewhere, in the design for Persian No 1, we see references to Islamic art, which were common in both father and daughter’s work. May travelled to Egypt and Morocco and built up a collection of textiles and other objects to which she often referred in her work. Minstrel with Cymbals (c1885), in turn, is based on a stained-glass window designed by William (c1867), used in several churches, including Llandaff Cathedral and Jesus College Chapel, Cambridge. May’s work rarely featured figures, so this is a singular example, thought to have been made to demonstrate her skills to potential commissioners.

Westward Ho! (early 1880s), on the other hand, is a rare example of a collaboration between May and her mother, with May creating the design and Jane completing the embroidery. Both this and Bunch of Grapes (c1882) demonstrate Morris’s penchant for the colour blue, of which she wrote: “Choose those shades that have the pure, slightly grey tone of indigo dye … reminding one now of the grey-blue of a distant landscape, and now of the intense blue of a midday summer sky – if anything can resemble that.”

Lily of the Valley (c1896) is, however, the most abounding example in the exhibition, showing the myriad ways in which one design might be adapted and realised, including as a mat, a wall hanging, a cushion or chair cover, a bag or a tablecloth. Its cascading swirls and delicate blooms interlace and overlap, like the tendrils of a sweet pea, and if a design could exude a scent, this one’s would be every bit as delicious as the two flowers put together.

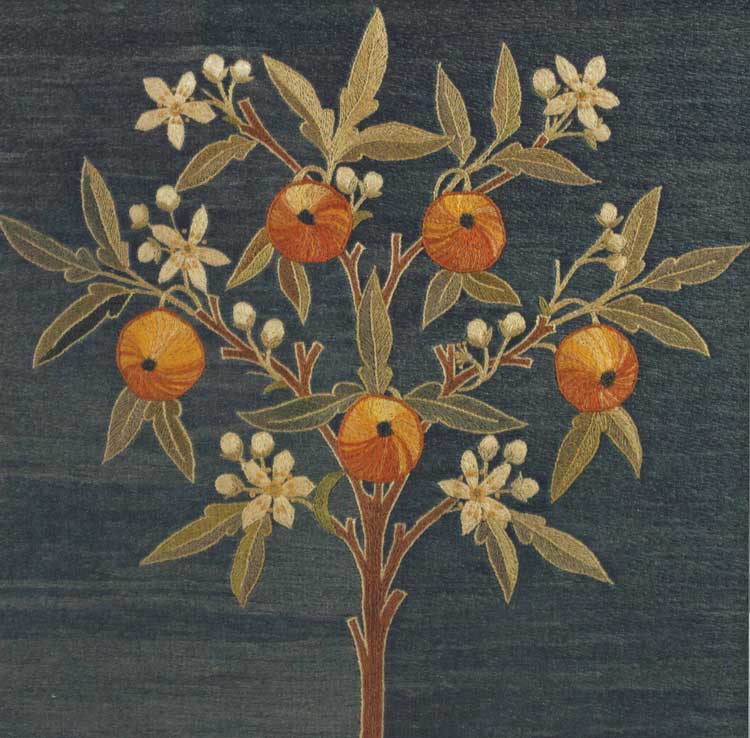

Orange Tree panel, designed and embroidered by May Morris, possibly c1897. Silks on linen, 41.8 x 43.5 cm. © William Morris Society, bequeathed by Helena Stephenson, 1970.

Throughout the exhibition, there are lots of activities for children (and grownup children!) to become actively involved, including pattern sheets to colour in, information on various stitches, and embroidery kits. The latter were something one could purchase at the time from Morris & Co, enabling clients to complete the work themselves. Each kit would have included a design marked in outline, accompanied by a small, completed sample section, and it would have been sold for a much lower price than the completed work – for example, £3 as opposed to £47 for a portiere (a curtain hung in a doorway).

Morris left the company in 1896, the year her father died. Mason said: “As a woman, she didn’t have control of any of her financial assets, so she then had to completely reinvent herself and carve out a freelance career … As a single woman living in London, what she did was really quite extraordinary.” May took the opportunity to expand her skillset beyond what Morris & Co had required of her, learning silversmithing and writing and lecturing on embroidery across Britain and America. In 1907, she also established the Women’s Guild of Arts, as a woman’s counterpart to the Art Workers’ Guild, which was open only to men. Throughout her life, Morris advocated for progressive political causes, attending socialist meetings with her father and contributing to political journals. She rallied against the injustices of industrialisation, capitalism, and class and gender inequality (she did not, however, join the Suffragette actions, placing more importance on socialism).

,-drawn-by-May-Morris,-1893-photo-by-Anna-McNay.jpg)

Design for January cushion (detail), drawn by May Morris, 1893, pencil and watercolour on paper © William Morris Society. Photo: Anna McNay.

The final years of her career were focused on ensuring her father’s legacy was preserved. She published 24 comprehensive volumes of his writings, with a biographical introduction to each (1910-15); two volumes on his artistic and literary achievements and socialist activism (1936); and she donated examples of his designs to the V&A for a proposed “Morris Room”.

In terms of her private life, following an affair with the playwright George Bernard Shaw – who wrote of how she managed to overcome the inherent tediousness of embroidery – Morris was married for four years to the political activist Henry Halliday Sparling. Their union did not last, however, and Morris divorced him. She spent her later years at Kelmscott Manor, the Morris’s family home in the Cotswolds, living with the erstwhile gardener, Mary Lobb, whom she described as “housekeeper, cook and companion, and I may add, my almoner”1 and of whom she said: “I should be lost without her.”2 On her death in 1938, Morris left Lobb more than £12,000 (almost £1m today) and secured her tenure of Kelmscott Manor for the rest of her life.

May Morris: Art & Advocacy, installation view, Russell-Cotes Art Gallery & Museum, Bournemouth,

5 April – 5 October 2025. Photo: Eliza Naden.

Morris’s striking appearance is well documented (and there are plentiful examples in this exhibition), thanks to the artistic social circle of her family, which meant that she was used to sitting for photographers and painters alike. Rossetti described her as “quite a beauty the more one knows her and will be a lovely woman”. Certainly, his portrait seems to exaggerate Morris’s best features (even as a child), rendering her, in the parlance of the pre-Raphaelite group, quite a “stunner”.

Mason said: “There is a sense with May that there is more to be discovered. Her work is incredibly visually captivating. She works at all kind of scales – very minute detailed work; very large expressive pieces. I think people are aware of her and want to know more.” This small but thorough exhibition portrays Morris as a trailblazing feminist, prolific artist and lecturer, and promoter of her father’s legacy. As she described herself later in life to Bernard Shaw: “I’m a remarkable woman – always was, though none of you seemed to think so.”3 Her work exemplifies the first principle of the Arts and Crafts movement, namely that the design and making of an object should be done by the same person in order to create a beautiful and practical work of art. As Lobb formulated it to the director of the V&A a month after Morris’s death: “You see William Morris could design embroideries but he could not embroider, anyway not as well … Mrs Morris could embroider but couldn’t design, Miss Morris could and did both design as well as William Morris and embroider as well [as] any one … and her colour arrangements were unapproachable and original.”4

References

1. A Well-Crafted Life by Jan Morris in May Morris: Arts & Crafts Designer, London: Thames & Hudson, 2017, page 27.

2. The Rich and Complex Character of May Morris, Designer, Embroiderer, Jeweller and Writer by Thomas Cooper in art herstory, 25 March 2023.

3. Morris, op cit, page 29.

4. ibid, page 31.