Edward Burra, Landscape, Cornwall, with Figures and Tin Mine, 1975. Private collection. © The estate of Edward Burra, courtesy Lefevre Fine Art, London.

Tate Britain, London

13 June – 19 October 2025

by CHRISTIANA SPENS

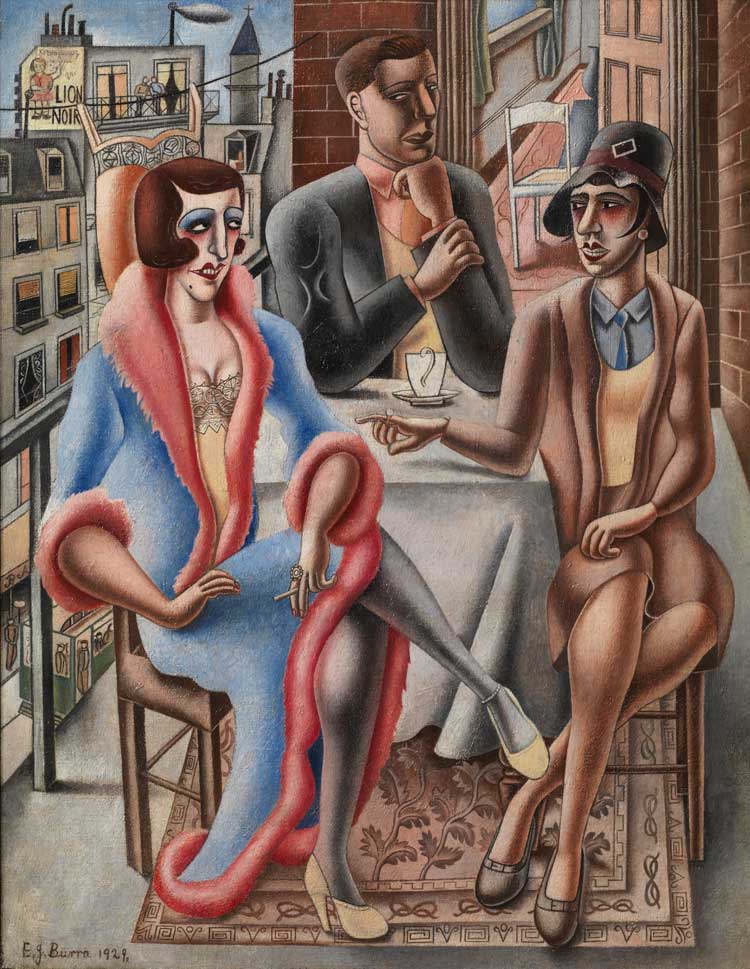

On entering Tate Britain’s retrospective of Edward Burra (1905-76), visitors are met with a large black-and-white photograph of the artist among some of his paintings; he is looking down, forlorn yet endearing, evading our gaze. As a child growing up in East Sussex, Burra was often ill, with rheumatoid arthritis and a blood condition, and perhaps this explains his somewhat frail demeanour. Encouraged by his parents to pursue his interest in art, he described it as “a kind of drug” that helped relieve his physical pain. Walking further into that first room of the exhibition, filled with paintings Burra produced when, fresh out of the Royal College of Art, he travelled to Paris and Marseille, there is a real sense of his art as something hedonistic and enlivening, too; girls dancing in Paris clubs, sailors congregating outside Marseille bars, a woman smoking in a cafe. Burra painted these scenes during the roaring 20s – what the French called the Années Folles (the crazy years) – and he truly captured the joy and flamboyance of the time. In Balcony, Toulon (1929), three glamorous figures cut a dramatic scene, yet there is an undercurrent of distrust; I am reminded of Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises, written in this period, and other literature of the Lost Generation, as they would come to be known.

Edward Burra, Balcony, Toulon, 1929. Private collection. © The estate of Edward Burra, courtesy Lefevre Fine Art, London.

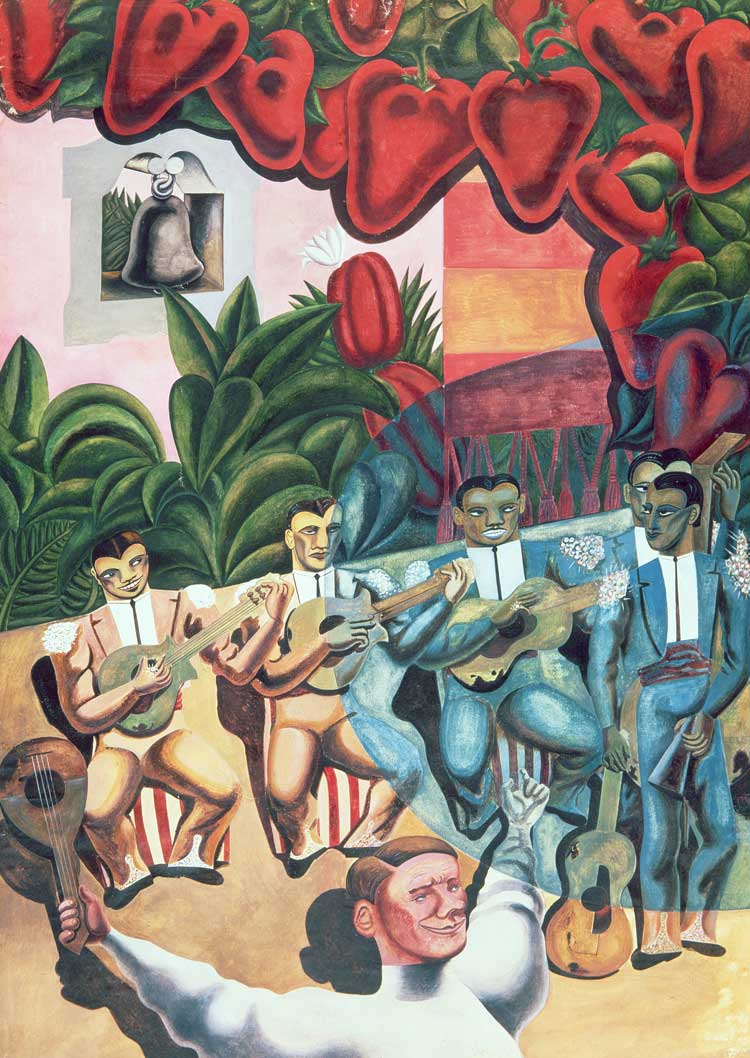

In 1933, Burra sought further adventures, travelling to New York and then to Boston, frequenting bars, clubs and music halls, and painting the jazz singers and musicians he came across. In Red Peppers (1934-35), six musicians playg guitars and banjos, with vibrant red peppers framing the scene. And in Savoy Ballroom, Harlem (1934), he creates an intricate, exuberant scene of people dancing. At the time, he wrote to his friend, the photographer Barbara Ker-Seymer: “We went to the Savoy dance hall the other night; you would go mad, I’ve never in my life seen such a display, an enormous floor half dark, surrounded by chairs and tables and promenade on one side and the band on the other with a trailing cloud effect behind … such wonderful dancing. It’s an experience not to be missed.” In a nice touch, the music playing in this gallery room is from Burra’s personal record collection, which is held in the Tate archive.

Edward Burra, Red Peppers, 1934-35. Dundee Art Galleries and Museums (The McManus). © The estate of Edward Burra, courtesy Lefevre Fine Art, London.

Burra was enamoured with Spanish culture and, before he had even visited the country, he painted scenes based on literature, music and art. In 1933, he finally went there, visiting Barcelona, Granada and Seville. When he returned to England, he produced a series of works that took on a more surrealist edge. Again, these scenes of cafes and bullfighting remind me of The Sun Also Rises; there is such a sense of Burra’s imagination and the way in which his love of art and literature determined where he went and how he lived, as if he were also one of those restless characters with whom he so identified.

In April 1936, Burra returned to Spain, this time to Madrid and witnessing first-hand the violent civil unrest that foreshadowed the civil war. As he wrote at the time: “One day when I was lunching with some Spanish friends, smoke kept blowing by the restaurant window. I asked where it came from. ‘Oh, it’s nothing,’ someone answered with a shade of impatience. ‘It’s only a church being burnt!’ That made me feel sick. It was terrifying: constant strikes, churches on fire, and pent-up hatred everywhere.”

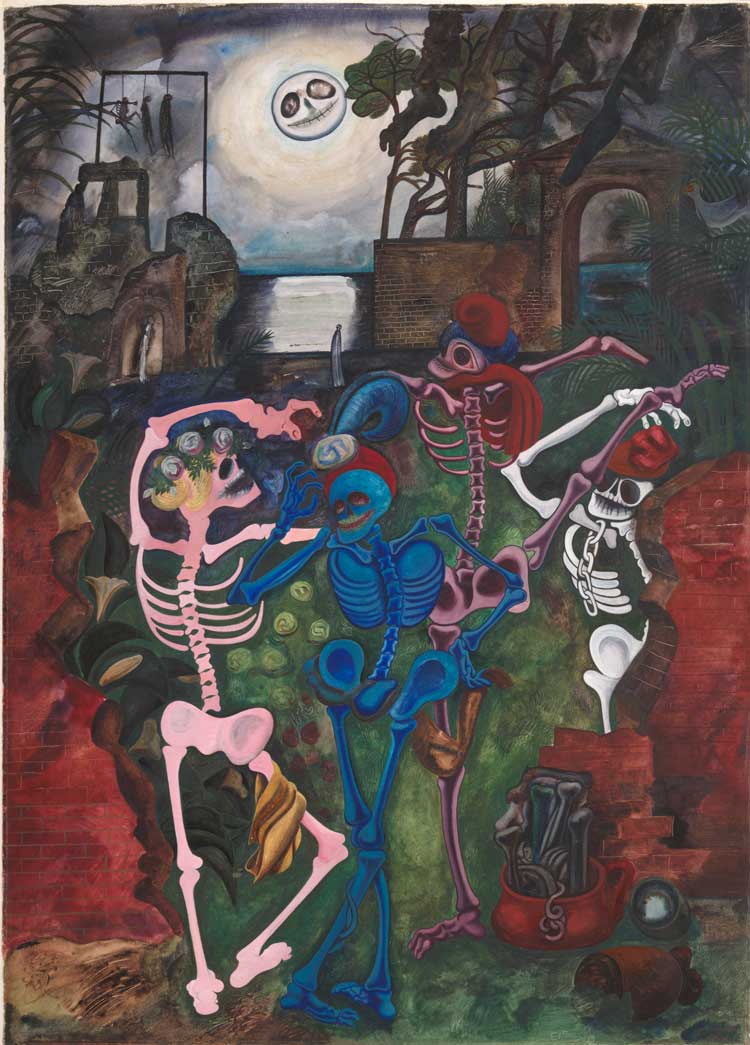

Edward Burra, Dancing Skeletons, 1934. Tate, Purchased 1939. © The estate of Edward Burra, courtesy Lefevre Fine Art, London.

Burra fled Spain that July to escape the escalating hostilities, and from then on the civil war transformed his practice and general outlook. His paintings from the period chronicle the destruction, drawing on newspaper articles and his morbid imagination, with paintings such as The Torturers (1935), in which masked nude figures wield barbed weapons, and Bal des Pendus (Dance of the Hanged Men) (1937), which portrays the construction of gallows and the hanging of civilians.

The second world war intensified this deep sense of horror that had been developing in Burra’s work. Living on the south coast of England again, he experienced the destruction of war: the heavy aerial bombardments, the presence of allied troops before deployment to the front. He was also isolated from his friends, and his physical state worsened due to rationing of the medicines needed to treat his illness. His mood darkened and his work reflected a morbid, depressed state of mind. In War in the Sun (1938), he depicted soldiers as evil beings taking over the countryside around his hometown, and visions of violence and doom. There are many paintings of soldiers, such as Soldiers’ Backs (1942), their bodies seeming to merge into one another and the machinery around them. In the diptych Wake (1940), shrouded figures in red look down on a skeleton in an open grave, recalling Goya’s Black Paintings, which were similarly dark and morbid in the wake of war.

Edward Burra, Soldiers at Rye, 1941. Tate, Presented 1942. © The estate of Edward Burra, courtesy Lefevre Fine Art, London.

In Soldiers at Rye (1941), monstrous masked figures roam around and in Ropes and Lorries (1942-3), a quiet country lane is beset with a convoy of military vehicles. At the time, he wrote to his friend Billy Chappell: “I’ve given up dearie and never go out … I really feel like DEATH and can’t go on.” Painting enabled him to process the horror around him, medicinal in a way it always had been for him, and yet his works reveal the toll that the war took and how it changed his attitudes to humanity more widely.

Despite these dark experiences, Burra did not lose his light-heartedness entirely. One gallery is devoted to his designs for costumes and stage, often in collaboration with his friend Frederick Ashton, for the Royal Opera House, Sadler’s Wells and Ballet Rambert. These recall his earlier flamboyant scenes of Paris, Marseilles and Harlem, and give some respite from his darker paintings.

Edward Burra, Cornish Clay Mines, 1970. © The estate of Edward Burra. Private Collection. © The estate of Edward Burra, courtesy Lefevre Fine Art, London.

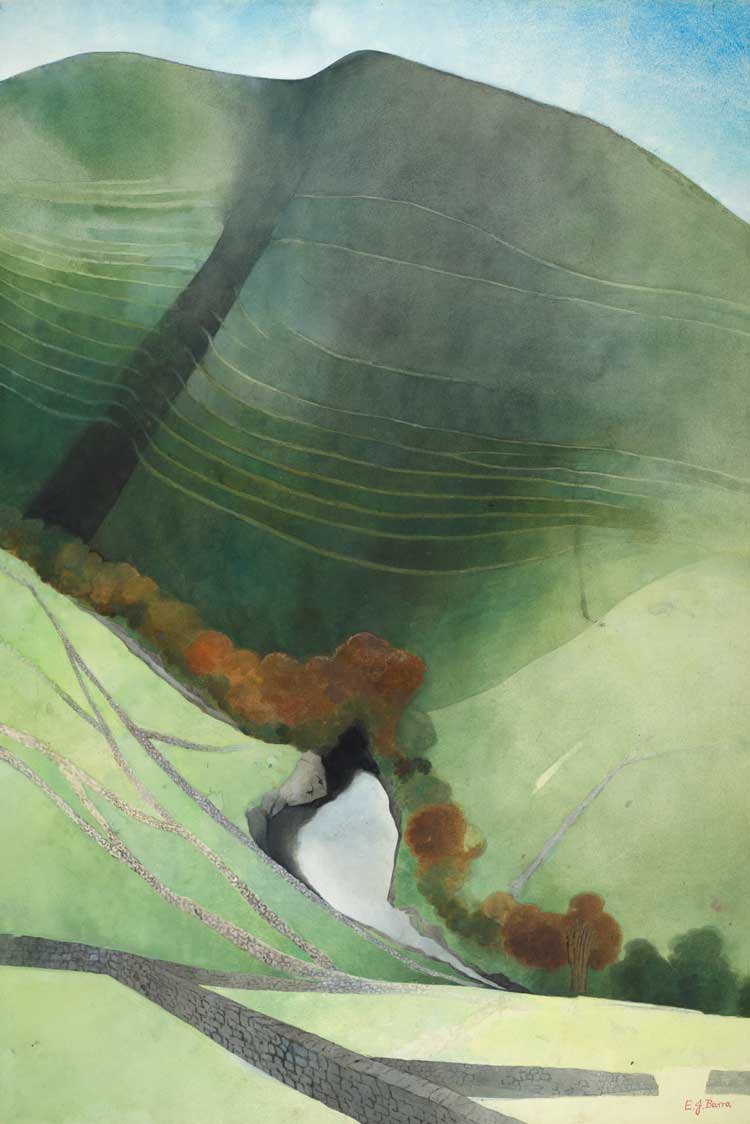

Burra did not travel so much after the war, mostly because of ill health, and so his travels were limited to driving tours of Britain and Ireland, particularly the rugged landscapes of Cornwall and the Lake District. No longer painting people so much, his attention turned to natural scenes of beauty and exploitation; in the wake of the postwar industrial revolution, Burra mourned man’s destruction of the countryside, such as in Picking a Quarrel (1968-69), in which he depicts monstrous diggers excavating a mountain, and Cornish Clay Mines (1970) showing mine shafts and a petrol station.

Edward Burra, Valley and River, Northumberland, 1972. Tate Collection. Image courtesy Tate Photography. © The estate of Edward Burra, courtesy Lefevre Fine Art, London.

Burra’s later paintings of war and environmental destruction seem particularly resonant now, and they are so intricate and devastating I find myself staying with them the longest, despite the horror they reveal. Burra’s deep compassion for the people he met, but also the places he loved, the natural world itself, somehow lifts the horror; from dancing girls and sailors to the onslaught of industry and war, Burra took in everything he saw and knew in a passionate and fearless way, and his work is breathtaking for it.