Jean-François Millet, The Wood Sawyers, 1850-52. Oil on canvas, 57 x 81 cm. Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Bequeathed by Constantine Alexander Ionides (CAI.47). © V&A Images / Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

National Gallery, London

7 August – 19 October 2025

by JOE LLOYD

It is a quotidian scene. Two peasants stand in a field, hands clasped and heads lowered in prayer. There is a basket of potatoes on the ground in front of them. It looks almost as if they are saluting these humble root vegetables. But there is a church spire on the horizon, and this inscrutable pair – spouses? siblings? master and servant? – are reacting to the tolling of its bell. Three times a day, French villagers would recite the Angelus prayer, at dawn, noon and dusk. Jean-François Millet’s The Angelus (1857-59) envisages the last of these three occasions, beneath a pale sun.

Jean-François Millet, The Angelus, 1857-59. Oil on canvas, 55.5 x 66 cm. Musée d'Orsay, Paris. © Musée d'Orsay, Dist. Grand Palais Rmn / Patrice Schmidt.

For all the scene’s straightforwardness, it contains multitudes. For the impressionists, it was a masterclass in how to handle light. Some commentators saw it as an expression of support for impoverished labourers, a nascent work of socialist art. Others found a conservative nostalgia for tradition. It gained a second life in reproduction as a Christian devotional image, though Millet’s own relationship with religion remains ambiguous. It was twice the most expensive painting ever sold. Vincent van Gogh called it “poetry” and made a copy. Salvador Dalí was haunted by it, referencing it over and over before penning a book on it. He had the Louvre X-ray it, revealing a shape that he claimed was an infant’s coffin. Few art historians have agreed with this interpretation. Yet the painting might still speak to grief. Life expectancy was low. The Angelus prayer asked Mary to intercede on behalf of the living and dead. The figures could be thinking of the spirits of those they had lost. Or they could be solemnly marking thanks that another day of hard labour is over.

Millet: Life on the Land centres around this masterpiece, a rare loan from the Musée d’Orsay. But this small yet substantial exhibition contains a further brace of enrapturing paintings and drawings by Millet. His last London survey was at the Hayward Gallery in 1976. But he has become a familiar presence in British museums. There was a late-19th-century vogue for collecting his works in Britain, which has led to a healthy distribution of masterpieces across the nation. Except The Angelus, all works here come from British collections, often bequeathed by private donors.

For much of western art history, rural labourers were painted either as ornaments to pastoral landscapes or bawdy rustics. Millet broke with these traditions. He was a realist painter who strove to depict ordinary subjects as they were. He worked from experience: he was himself born to a prosperous farming family in Grouchy, Normandy, and spent his youth helping in the fields. Millet later moved to Paris for two periods, where he would translate his childhood landscapes into paint. From 1849 to his death in 1875 he lived in Barbizon, a village south of Paris on the edge of the Fontainebleau Forest, where he became one of the leaders of a school of realist painters.

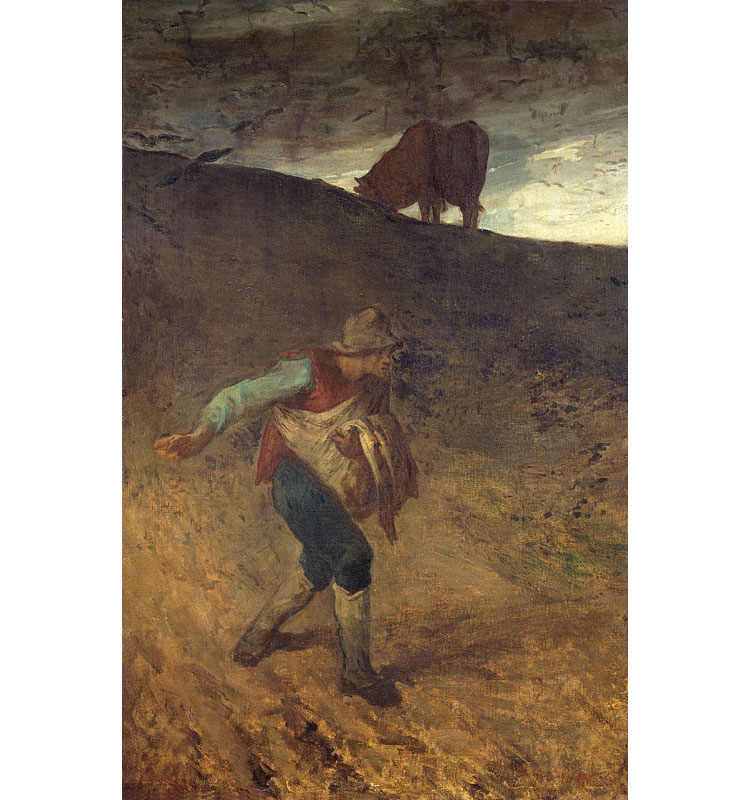

Jean-François Millet, The Sower, 1847- 48. Oil on canvas, .95.3 x 61.3 cm. Lent by Amgueddfa Cymru – Museum Wales. Bequeathed by Gwendoline Davies in 1952. © Amgueddfa Cymru - National Museum Wales.

Millet did not reject previous depictions of countryside life. He was an admirer of Pieter Bruegel the Elder. The subject of The Sower (1847-48), the first version of a painting Millet exhibited to great success at the 1850 Salon, wears a hat that could have been worn by one of the Flemish master’s celebrating peasants and, like Bruegel, Millet captures his protagonist’s potent movement. But unlike his carousing ancestors, the sower is a faltering figure, stepping forward with trepidation. Birds gather in the sky, eager to undo his labour. The cragged land looks as if it might swallow him up. Millet’s figures are often alone with the land. Even those working in tandem can still feel isolated. In a stupendous crayon drawing of A Man Ploughing and Another Sowing (1849-52), the two men seem to be living on parallel tracks, alienated from each other as much as their labour.

Jean-François Millet, A Man Ploughing and Another Sowing, 1849-52. Black crayon on paper, 14.5 x 21.2 cm. The Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford. Bequeathed by Percy Moore Turner, 1951. © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford.

This is the real countryside, not a bucolic fantasy. Émile Zola in The Earth, his monumental depiction of rural life, wrote of “terrible seasons of famine, sudden excesses of all sorts, dreadful periods of destitution during which men nibbled the grass beside the ditches, like beasts of the field”. There is no grass-nibbling at the National Gallery, but you get the sense that the more impoverished of his labourers could easily be reduced to it. A drawing of A Shepherdess (c1850-5) has its subject leaning against a spiky thicket, which appears as if it might engulf her. She is knitting: never a moment to spare. We see Faggot Gatherers (in a large unfinished painting from 1868-75) slouched under the weight of their loads. In a smaller depiction of the same subject from 1850-55, a young woman stands while her aged colleague sits in exhaustion, her fingers crooked from years of toil.

Jean-François Millet, A Shepherdess, about 1856. Black chalk with touches of blue chalk on pale buff paper, 22.8 x 15.1 cm. National Gallery of Scotland. Mr A.E. Anderson Gift 1929. © National Galleries of Scotland.

There remain questions as to how Millet related to his subjects. He identified with the peasantry: “A peasant I was born, a peasant I will die.” He sometimes wore clogs to underline this connection. Yet in his work, humility is often joined with a heroic quality. The pair in The Angelus are monumentally scaled, like figures in a neo-classical history painting (Millet trained under Paul Delaroche, a paramount example of his genre). His drawings sometimes show the sort of Herculean musculature favoured by Michelangelo. His characters’ outfits make their wearers grander, almost sculptural. The journalist Charles Bigot noted that Millet’s clothes are “massive and worrying, and it was surprising that they did not crush those who wore them”. A Milkmaid (c1853) seems almost armoured by her heavy skirt. She holds her copper milk can on her shoulder like a warrior laden with booty.

Jean-François Millet, The Winnower, about 1847-48. Oil on canvas, 100.5 × 71 cm. The National Gallery, London. © The National Gallery, London.

Preparatory drawings for The Winnower (1847-48), Millet’s first large-scale depiction of his great topic, show a detailed, closely observed face. But in the painting itself the Winnower is half-turned away, his features cast in shadow. The central figure in The Wood Sawyers (1850-52) – a painting whose rhythmic brushwork pre-empts Van Gogh – is experienced as an almightily posterior clad in blue trousers. Even in The Angelus, where the male farmer’s face is angled down towards the foreground, his face is a blur. Is this the result of Millet’s propensity to paint from memory rather than direct observation? Or is he transforming these people into archetypes or symbols? The ostensible simplicity of Millet’s scenes and subjects hides an inexhaustible depth.