Maki Na Kamura in her studio, April 2023. Photo: © Maki Na Kamura. Courtesy Michael Werner Gallery, New York and London.

by ANGERIA RIGAMONTI di CUTÒ

“The Figure wanted to emerge, but the Landscape would not allow this to happen. Trapped in the air of becoming, in a way suffocated by the surrounding foliage-sludge in which it found itself ensconced.”1

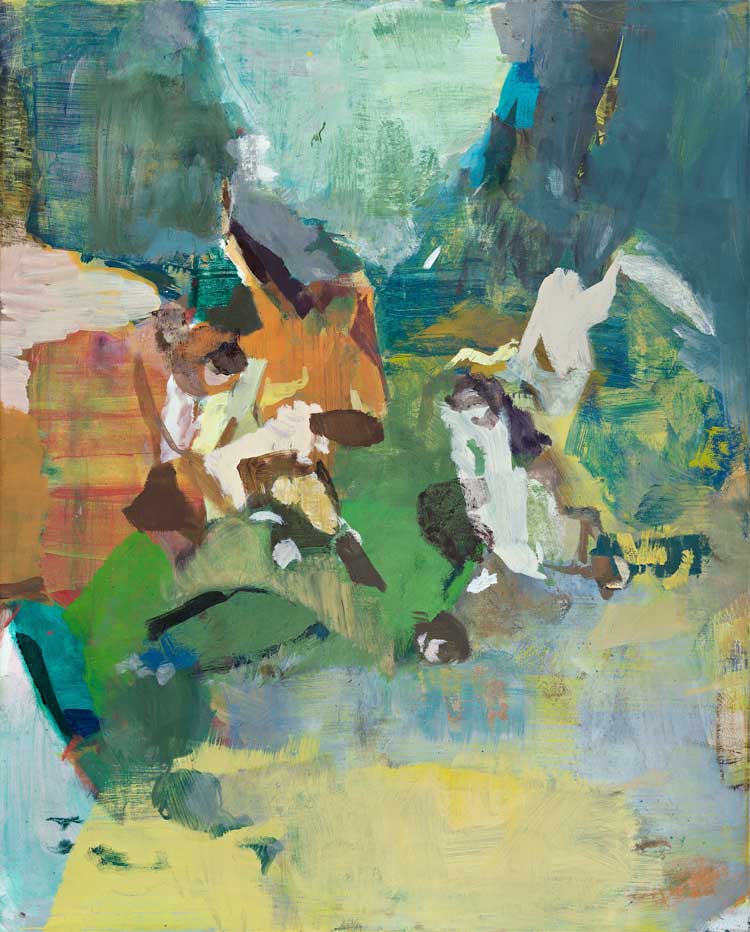

Aptly, the exhibition catalogue text accompanying a suite of paintings by Maki Na Kamura (born Osaka, Japan) takes the form of an ekphrastic poem, a composition that conjures up the elusive nature of the artist’s images, with their almost-but-not-quite recognisable elements of landscapes and figures. Quicksand-like, these intimations ultimately evade the viewer’s grasping eye and mind. Kamura’s figures “crave emergence”2 but are never allowed definition or autonomy within her suggestive fields of colour that tenuously infer the presence of human figures, water, skies, trees and fleeting horizon lines. For all this pictorial mystification, she designates many of her works as landscapes in a sui generis system of titles, with a longstanding series bearing the initials LD, for Landschaftsdarstellung, landscape representation.

Maki Na Kamura, Claim of Babylon II, 2023. Oil, tempera on canvas, 200 x 260 cm. © Maki Na Kamura. Courtesy Michael Werner Gallery, New York and London.

At times, specific art historical references have been identified in Kamura’s work: Giorgione, Nicolas Poussin, Pierre Puvis de Chavannes and Jean-Francois Millet – and she describes herself as both a contemporary and traditional painter – but it is preferable to take in these paintings on their own terms and submit to their slightly destabilising, alluring presence, with viewers, as Kamura suggests, free to project their own associations.

Angeria Rigamonti di Cutò: The encounter with Japan was crucial to the development of European art in the 19th and 20th centuries. In your work, certain western art historical references have been perceived, so I wondered what early encounters you had with European painting that particularly stirred you?

Maki Na Kamura: My grandmother stopped smoking when she turned 60. She had a pack of cigarettes and a matchbox showing a nice print on it. They were never touched again. Years later, I saw a Toulouse-Lautrec at a museum for the first time. It reminded me of that matchbox. And now I can’t say whether the print on the matchbox was Japanese or European.

Locating the centre of the art world in specific decades like Paris at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries was relevant before the days of the internet. Today, we have a worldwide centre. Next, I think this will soon be over, as I have felt for decades a demand for the centre to be in a smaller and more distinct place.

Maki Na Kamura, Ed XIII, 2023. Oil, tempera on canvas, 160 x 210 cm. © Maki Na Kamura. Courtesy Michael Werner Gallery, New York and London.

ARC: Was your home environment one that fostered an interest in art?

MNK: A child with an animal nature was trained to be a human being with the appropriate discipline. There was no way out, I had to provide my own entertainment.

ARC: Why were you particularly drawn to the German painter Jörg Immendorff – who had been a pupil of Joseph Beuys – to the extent that you left Japan with a one-way ticket, to study with him?

MNK: Despite the common description of him as a political painter, in my eyes, Immendorff was a naive romantic painter. As if he was trained well as a child. I could sense it. Another connection was “the Akademie”. In different ways, this place played a part in each of our biographies.

Once, I developed a concept for a group show under the title Three Generations at Kunstakademie Düsseldorf [2002]. I went to Immendorff, persuaded him to loan some works, and, with these works and my own, occupied a private museum in Japan that also collected works by Beuys. The loans were four small works and a large self-portrait of Immendorff. The latter is now in the collection of the National Museum of Art in Osaka.

Maki Na Kamura, Ed XIV, 2023. Oil, tempera on canvas, 140 x 190 cm. © Maki Na Kamura. Courtesy Michael Werner Gallery, New York and London.

ARC: It seems that an important aspect of the distinct visual language you’ve developed is an encounter of diverse landscape traditions, and of abstraction and figuration, in a way that doesn’t water down any of those strands. How calculated was this synthesis, or was it a more instinctive, less thought-out process than the question implies?

MNK: I just try to realise an idea to create valid contemporary paintings. People in the presence of my work can project their memories of all kinds of genres of bygone paintings on to them because I am a traditional painter.

ARC: Rather than the expected essay, the text for the exhibition catalogue is an ekphrastic poem that conjures up this ambiguous and elusive quality of your paintings, describing the refusal of the figures to emerge distinctly from their environment. Why do you not want the viewer to grasp the figures, which are nearly, but not quite, discernible?

MNK: I had an idea to design this catalogue a bit like the lyrics of a song, and not an introduction to the works. When thinking in painting, I rather avoid figures acting narratively. The narrative should remain abstract or analytic.

Maki Na Kamura, Ed XV, 2023. Oil, tempera on canvas, 210 x 160 cm. © Maki Na Kamura. Courtesy Michael Werner Gallery, New York and London.

ARC: In addition to the visual suggestions of figures and landscapes, other aspects of these pictures evoke history painting, such as the sweeping scale of some works and the titles, with their Roman numerals and references to Babylon. What are you aiming for through these enigmatic, fleeting titles (a recurring word is “escape”)? Are they another means of playing with different spheres of time and space?

MNK: When I was six, standing in front of a painting at a museum and pointing to the label, I asked my aunt: “What does this mean?” She said “Untitled” and explained its meaning, which made me furious. Since then, I’ve been protesting against “Untitled”.

ARC: Regarding your technical process, I’ve read that you sometimes work from existing images, scanning and printing them to give you a basis on which to develop your paintings. Can you describe your method and whether it’s changed over the years?

MNK: Most of the images I look for and find contain specific visual ideas that are at odds with the descriptions found in art history books. Since I work a lot with structures and textures, my eyes are trained to spot such patterns in the flood of images, be they reproductions or originals. In other words, it’s not about how the image material in question is ultimately processed. The processed images may be used as a stimulus, by me and by the viewer – or not.

Maki Na Kamura, Ed XVII, 2023. Oil, tempera on canvas, 155 x 125 cm. © Maki Na Kamura. Courtesy Michael Werner Gallery, New York and London.

ARC: In terms of medium, you use tempera and oil within the same painting. Most of your canvases have a rather matt finish with small, isolated areas of quite a dense impasto of oil. How does your distinctive combining of oil and tempera fit in to your scheme of things?

MNK: Mixing oil and water is not as contrary as it sounds. Lotion for your face is one example. Mayonnaise with eggs as a binder is another, which I use more or less in the same way. Painting is an irrational, complex subject, always consisting of combinations of different materials. And people see in it something which is there and at same time something which is not there. All of this is already magic.

ARC: There is something very kinetic, even cinematic, about viewing your paintings. As you start looking at them, the eye and brain inevitably begin trying to apprehend the whole image and its various elements but, not quite being able to take hold of something, keep moving as the image moves. It’s quite a giddy experience. Are you purposely trying to make a static image, and its relationship to the viewer, as dynamic as possible?

MNK: The viewers of my paintings sometimes surprise me with reports of their lively experiences, and I appreciate it.

References

1. Travis Jeppesen (2023), The Figure (after a suite of paintings by Maki Na Kamura, Maki Na Kamura, London: Michael Werner Gallery

2. Ibid.

• Maki Na Kamura is at Michael Werner Gallery, London, until 17 June.