Eduard Ole. Passengers (Reisijad),1929. Art Museum of Estonia. Photo: Stanislav Stepaško.

Museum Gunzenhauser, Chemnitz

27 April – 10 August 2025

by SABINE SCHERECK

In Germany, the artistic movement of the new objectivity in the 1920s and 30s is a crucial one, representing the zeitgeist of the brief period known as the Golden Twenties. But the style was part of a wider realism movement across Europe, and the Museum Gunzenhauser is the first to present this border-crossing perspective of it – and it does so on a large scale.

The inspiration for this show was curator Gustav Friedrich Hartlaub’s 1925 art exhibition in Mannheim for which he coined the term “new objectivity” to describe the burgeoning new artistic style. The Kunsthalle Mannheim celebrated this centenary last November in grand style with the breathtaking exhibition The New Objectivity, which also looked at the European development of the style and included female artists, since no women were included in the 1925 exhibition. Hartlaub’s exhibition had also toured to Chemnitz, so the Museum Gunzenhauser is picking up a thread within its city’s history. And, like the Kunsthalle Mannheim, it has made a point of including female artists. Among them are well known names such as the German Swedish painter Lotte Laserstein and the German Kate Diehn-Bitt (who also featured in Mannheim), but the focus is on many new discoveries, including Aleksandra Beļcova (Latvian Russian), María Blanchard (Spanish), Veronica Burleigh (British), Stina Forssell (Swedish), Vilma Kiss (Hungarian), Milada Marešová (Czech), Ángeles Santos (Spanish), Ekaterina Savova-Nenova (Bulgarian) and Gerda Wegener (Danish). They prove that female artists were active throughout Europe.

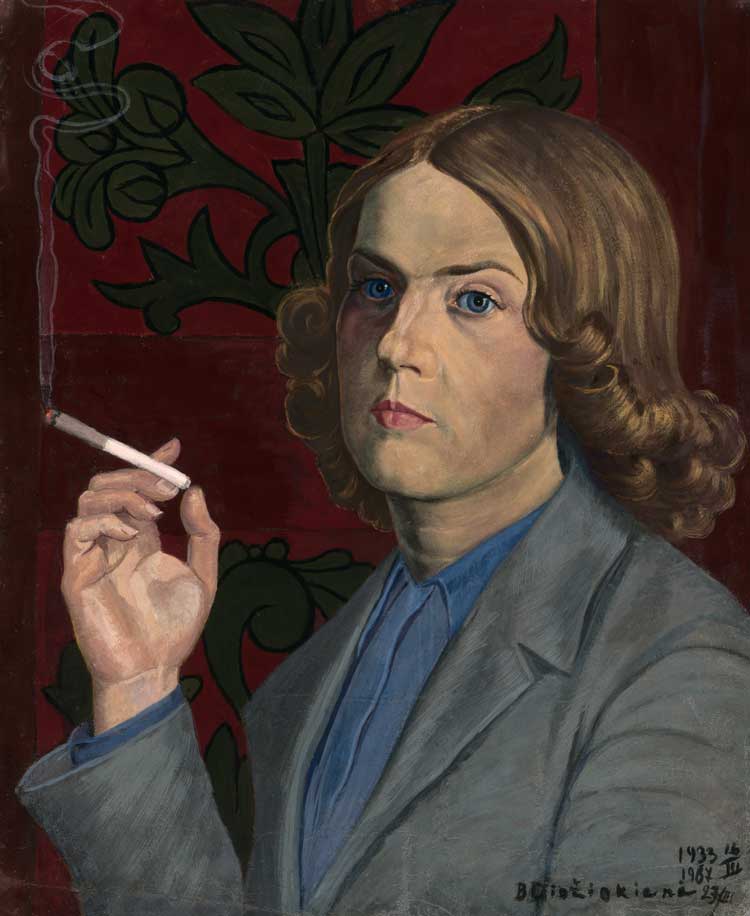

Barbora Didžiokienė. Self-portrait, 1933–1967. Photo: Antanas Lukšėnas.

The exhibition focuses on the northern, eastern and southern parts of the continent, which are rarely considered in the writing of art history, which concentrates mainly on western Europe. This pan-European view brings to the surface artistic influences from the past as well as from different regions, as artists often travelled, soaking up the characteristics of their new environment. In the early years, this was motivated by seeking advancement in their craft when reaching artistic hubs such as Paris, Rome or later Berlin, where they met fellow artists, exchanged ideas, forged connections and created networks. Later, journeys were forced on artists persecuted in their home countries by the political rise of the right. This flow of movement is well illustrated through a video graphic showing a map of Europe with its artistic centres and how they waxed and waned between 1918 and 1939. Beyond the already named cities, the map also includes London, Amsterdam, Dresden, Vienna, Prague, Zagreb, Vilna, Riga, Tallinn, Helsinki and Stockholm.

On an individual level, these movements are neatly outlined on a small map next to each painting tracing the artist’s journeys. Wegener (1886-1940), for example, travelled from her Danish birthplace in Hammelev to Paris and Morocco before returning to her home country and settling in Frederiksberg, where she died. She is represented here with the painting In the Heat of the Summer (1924), which portrays a blond nude from the back, Lili Elbe. The painting is held in a private collection.

The German Czech painter Ernst Neuschul (1895-1968) was born in Aussig (today in the Czech Republic), and his journeys zigzagged between Prague, Moscow, Berlin, London, New York and via Berlin back to London. In fact, these are just key stops and a closer look at his biography reveals visits to other cities, including Vienna, Krakow and Paris. His first wife was a dancer, whom he accompanied when she toured Europe, Asia and America. His second wife helped to get his works out of Berlin, when he was forced out of Germany because of his Jewish background, which eventually brought him to Britain, first to Swansea, then to London. On show here is Black Mother (1931), which captures a black woman in a modest blue coat and cloche hat sitting on a park bench breastfeeding her child. The painting is part of the collection of Leicester Museums and Galleries.

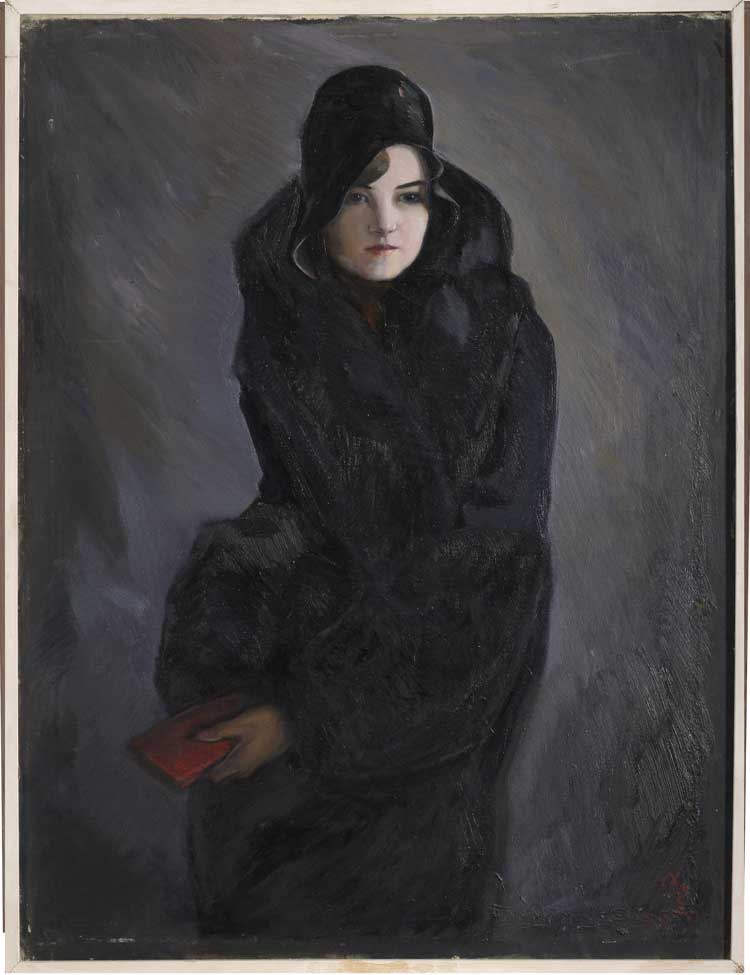

Peet Aren. Lady in Black, 1931. Oil on canvas, 92 x 70 cm. Art Museum of Estonia.

The course of Peet Aren’s (1889-1970) life led from his native Odiste in Estonia to St Petersburg, then to Tallinn and then Tartu in Estonia, and escape through Germany to his final destination, New York. His work Lady in Black (1931) is of a genteel-looking young woman in a black fur coat and black cloche hat. Her face, with its pensive expression, is outlined by wavy black hair. The painting’s home is the Art Museum of Estonia, Tallinn. Where a work is held gives further clues as to which places appreciated the artist and his or her international links. Some of the wall texts in the exhibition also provide valuable short biographies of the artists on display, as many will be new to visitors.

So much for the intricate underlying concept of the exhibition. Ambitious and comprehensive, it spreads across three floors and includes 290 works by more than 60 artists from 20 countries. Two hundred and eighty of the works are from European collections, and many have not been shown in Germany before, or even left their home country.

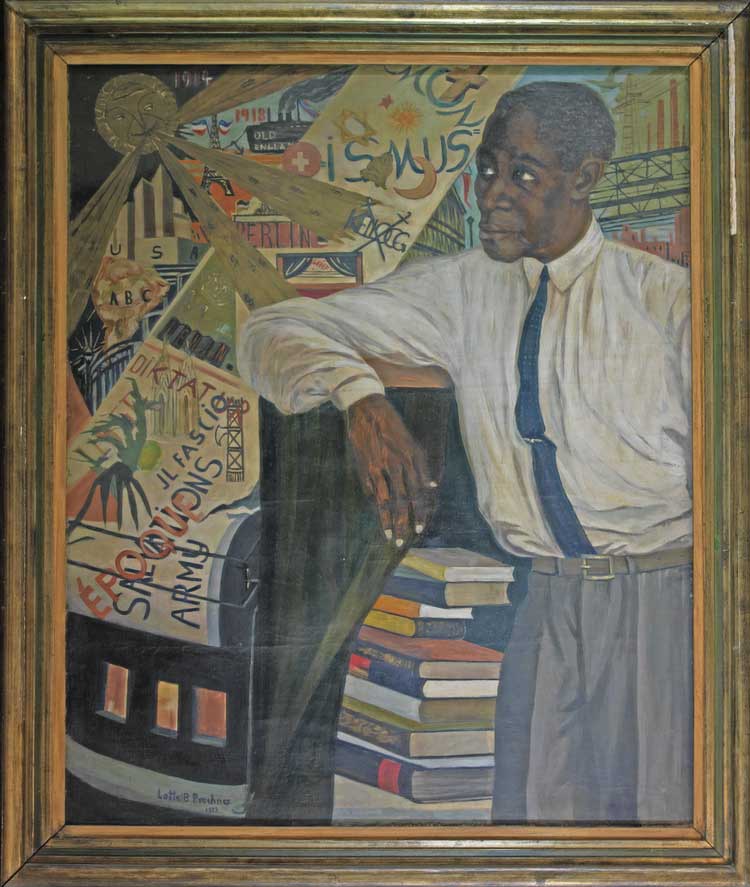

The curator, Anja Richter, organised the works by theme rather than country, bringing to light that realist movements were present across Europe. The curation also enables viewers to immerse themselves in the society of the period and get a sense of what everyday life was like for people across the continent. It takes the viewer to cities, with their haunts and famous nightlife spots, to sports events, to people’s workplaces and homes when portraying them, but also to quiet places when capturing still lives. People were also surrounded by the changing industrial landscape: there are depictions of bleak factory buildings, but also signs of advancing technology, with the excitement sparked by radio as a new mass medium. There was also increasing poverty as well as the emancipation of women, producing the so-called “New Woman”, whose modern lifestyle challenged traditional gender norms and structures.

Lotte Prechner. Epoque, 1928. Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung e. V.

The nightlife section is a great example of how the desire for dancing was prominent across Europe. The array of artists and countries is impressive. From Britain, there is William Roberts’ The Jazz Party (1921); from Germany, Max Beckmann’s Dancing in Baden-Baden (1923); from the then Czechoslovakia, Marešová’s Charity Bazaar (1927); from Spain, Josep Mompou Dencausse’s Dancing (The Cabaret Excelsior) (1929); from Poland, Stefan Płużański’s Café (1934); and from Latvia, Sigismunds Vidbergs’ graphic work In the Schwarz Café (1928). Seeing these pictures lined up together makes clear that it is not possible by looking at them to determine where they came from, and that style and subject prevail over origin in the movement. One reason for this is the socio-historical background out of which the realism movement was born. After the first world war shook up Europe, the map was rejigged creating new states as well as new political systems, particularly democracies. This created a desire for order and clarity, and in democratic countries brought freedom of expression.

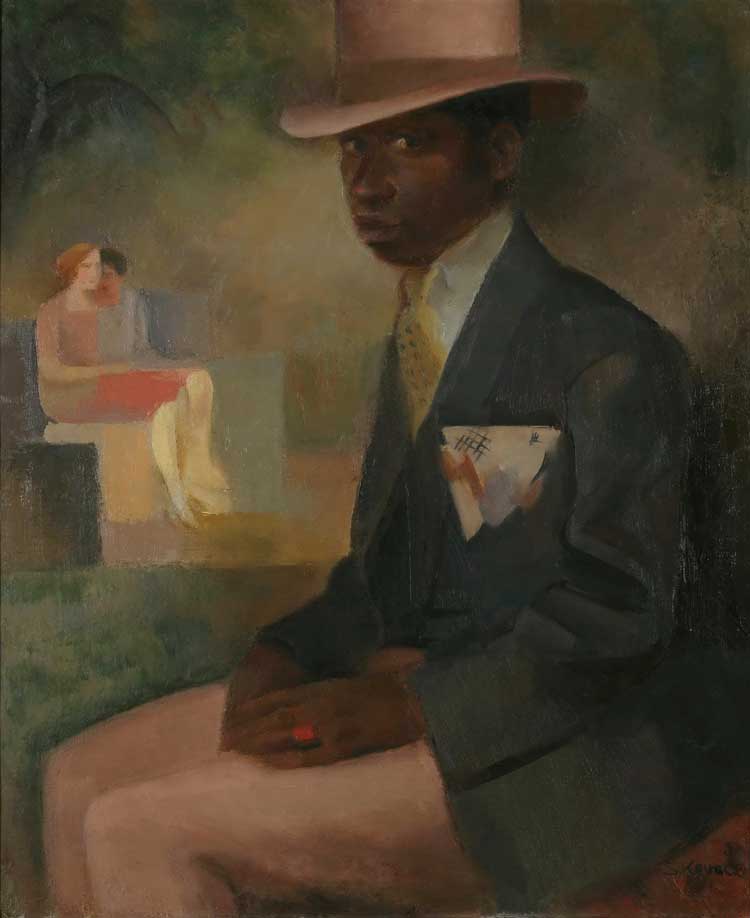

Sonja Kovačić-Tajčević. Man with Pink Hat,1930-32. Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art collection in Rijeka, Croatia. Photo: Goran Vranić.

Boxing was a popular entertainment at this time. A small series of works, cleverly combined with radios from the period blasting out animated sports commentaries, brings the excitement surrounding this new medium to life. For those who could afford it, leisure also meant engaging in sporting activities: tennis, swimming and skiing are all represented here. In the eye-catching Bathers (Balaton Beach) (1930s), by the Hungarian Károly Patkó, in which a small sunlit jetty stretches into an aqua-blue lake, people in colourful bathing suits climb into the water, or bask in the sun, chatting, watching the world go by or playing with children. It is a fascinating mix of liveliness and calmness: it pictures a simple summer’s day, yet, in its clear bright colours evokes the pleasures of it. The most arresting image in this series, however, is the innocuously titled Winter Sports (1930) by the Spanish artist Pere Pruna Ocerans. The painting shows two young women on skis, in which one is catching her companion, holding her around the chest, while the falling skier looks up at her rescuer. They could simply be friends, but there is a clear sense that there is more to it. An additional clue is the colour of the clothes of the falling skier: her red jumper representing love and her green cardigan symbolising hope. Her rescuer is clad in plain brown and looking towards the sky in the act of lifting her friend. It is a scene I have not come across elsewhere, which makes it so intriguing.

Alice Bailly. A Cold Morning in the Jardin du Luxembourg, 1921. Kunst Museum Winterthur, Schenkung von Georg Reinhart, 1928. Photo: SIK-ISEA, Zürich, Jean-Pierre Kuhn.

They are modern women and in the section Emancipation and the New Woman an impressive number of women are represented. Aren’s Lady in Black is placed next to Alice Bailly’s A Cold Morning in the Jardin du Luxembourg (1921), the latter showing a short-haired young woman wearing a smart black coat with fur and a black hat. The abstract black eyes of Bailly’s woman give her a slightly more cheerful look than Aren’s and the light brown background makes the painting less gloomy, although it suggests a late autumn or winter’s day. The curator’s skill in placing portraits that are akin in spirit is evident in several places and results in striking discoveries. A counterpart to these women in black can be found several rooms away, where Meredith Frampton’s Marguerite Kelsey (1928), which was recently displayed in Mannheim, hangs next to Sergius Pauser’s Lady in White (Mrs Beck, née Sokal) (1927). The similarities are striking – they almost mirror each other in content and clear style. Both women, seated and looking into the distance, wear plain long white dresses, have very short black hair and pale complexions. Next to them are flowers on a table and the wall in the background is terracotta coloured. It makes you wonder if they knew of each other’s work.

Sergius Pauser. Lady in White (Mrs Beck, née Sokal), 1927. Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg. Permanent loan of the city of Nuremberg.

The section on women also hosts the aforementioned Black Mother by Neuschul and Wegener’s Heat of the Summer portraying Lili Elbe. There is more to the latter than meets the eye. Elbe embodies a particular facet of the period: the question of gender, identity and gender fluidity, with women adopting male attire and engaging in what were seen as male activities such as driving sports cars, and some men daring to wear women’s clothes to reflect how they felt inside. By presenting Elbe from the back as a blond female nude crouching on an armchair, her gender remains unseen. Gazing sadly and longingly at an unfolded hand-held fan depicting, barely visible, a few women, discloses her sorrow. Elbe was, in fact, born Einar Wegener and six years after the painting was done, travelled with his wife, Gerda, to Berlin and Dresden in 1930-31 for pioneering gender-affirming surgery. The 2015 film The Danish Girl (based on David Ebershoff’s 2000 novel) brought her story to a wider audience.

Wandering through the exhibition, the serious, sober expressions of the women is noticeable, making Franz Lerch’s The Painter Roxane Zurunić (1930), with her refreshing smile at the viewer, stand out. It captures a woman pleasantly content with herself.

Among these many female portraits is a small series, which is set apart from the others in that the women are placed in front of a landscape with a horizon far in the distance, reminiscent of Italian renaissance portraits featuring a view from a window. Christian Schad’s Bettina (1942) and Herbert von Reyl-Hanisch’s Marianne Reyl (1930) are both wearing necklaces, as did the well-situated Renaissance woman. With the woman in By the Hills (1939), Gerald Leslie Brockhurst accentuates the chest with a blue scarf. Common to all is a gloomy surreal edge, owing to the unrealistic, jarring lighting between the women in the foreground and the landscape in the background.

Stina Forssell. Window to the Backyard (Fönster mot bakgård), 1933. Stiftelsen Bohusläns Museum.

A quirkier observation of the period derives from its still lives: the fondness for green plants, particularly cacti, which were popular at the time. Window to the Backyard (1933), by Forssell, a view from the top floor of a tenement building showing the flats opposite, captures a familiar sight for those who have lived in cities such as Berlin or Paris. The potted plants on the windowsill heighten that feeling of familiarity with its snapshot of everyday life.

Kiril Tsonev. Portrait of Svetoslav Minkov, 1939. Sofia City Art Gallery, Photo: Svetla Georgieva.

Another noteworthy section is Human Likenesses. Though it offers a great panorama of characters, male portraits, especially men pictured in their work environment, dominate. Here, too, are images with astonishing similarities: German painter Heinrich Maria Davringhausen’s The Profiteer (1920-21), the Bulgarian Kiril Tsonev’s Portrait of Svetoslav Minkov (1939), and the Russian artist Nicolai Wassilieff’s Portrait of a Man (1929). They all feature serious looking men in shirts and ties, sitting in their offices with views out of high-rise buildings that echo New York’s cityscape. Prominent, too, are the brown, red and grey tones and hard straight lines forming geometrical shapes.

This article can give only a glimpse into this vast show, which presents a major feat in the reassessment of art history. The visitor becomes a time traveller passing through the different worlds populated by the many characters within society: the well-to-do, the managers, the entrepreneurs, the office clerks, the workers, the sailors, the farmers, mothers and street girls, seeing them in dance halls, at sport events, at work and at home – not in one country but across Europe. In addition, although all works come under the heading of realism, the artists sport different artistic styles, which make the exhibition in many respects an extraordinary show.