Jaune Quick-to-See Smith: Wilding, installation view, Fruitmarket, Edinburgh, 7 November 2025 – 1 February 2026.

Fruitmarket, Edinburgh

7 November 2025 – 1 February 2026

by VERONICA SIMPSON

In the introduction to the excellent catalogue for this show, the Fruitmarket Gallery director, Fiona Bradley, opens with a quote from Jaune Quick-to-See Smith: “My work comes from a visceral place – deep, deep – as though my roots extend beyond the soles of my feet into sacred soils. Can I take those feelings and attach them to the passerby? To my dying breath, and my last tube of burnt sienna I will try.”

And try she did, allegedly completing one of the drawings in the upstairs room the day before she died, unexpectedly quickly, from pancreatic cancer, in 2025. Smith posed this question in the 1990s, but it underpinned the conversations she and Bradley had while devising this show. The thread that ties it to Fruitmarket’s programme is the idea of land and ownership – subjects close to Native American narratives and those of the Highland Scots, whose homes and livelihoods were ruthlessly demolished in the Clearances, between 1750 and the mid 1800s, with landowners removing people and communities in favour of more profitable sheep.

Bradley says: “Jaune wanted to spend time in Scotland to better understand the history and politics of land here as part of her preparation for her exhibition … As it turned out, that wasn’t possible: illness overtook her. The exhibition shifted from being a slice through the continuum of her thinking, climate activism and artmaking, to being a first posthumous presentation, with sculpture and painting made right up until she could no longer work.”

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, I See Red: 10,000 Years, 1992. Courtesy the Tia Collection. Image courtesy of The Estate of Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Garth Greenan Gallery, New York and Stephen Friedman Gallery.

Unlike many of the elder stateswomen of Indigenous communities being discovered or rediscovered and reappreciated, Smith made her mark in the 1980s, when she was setting up co-operatives to promote and exhibit the work of other Native American artists. It was 2020 before she sold a painting to a nationally significant collection – the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC (a painting from the I See Red series); it was the first Native American work it had acquired. And she had to fight so hard to get there. Born in 1940 on the Flathead Reservation in Montana, at the age of two, she was deserted by her mother and left in the care of her father, a horse trader. Her childhood was spent travelling across the north-west coast and California, often working in the fields alongside migrant workers.

Apparently, at 12 she saw John Huston’s 1952 film Moulin Rouge, about Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, and decided there and then that she wanted to be an artist. She photographed herself as Lautrec, drawing a moustache on to her face. A fascinating essay in the catalogue by Suzanne Fricke relates these biographical details and explains how she was discouraged from pursuing art or going to college, being told emphatically that this was a path open neither to women nor Native Americans. She prevailed, first earning an associate of arts degree in 1960 from Olympic College in Bremerton, then took classes at the University of Washington in Seattle, before dropping out because of lack of funds. In 1976, she finally achieved a BA in art education from Framingham State College (now Framingham State University), and then – on her third attempt – she won a place on the MFA programme at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, completing it in 1980.

She was passionate about promoting other Native American artists and, in 1977, founded the Grey Canyon Group, a collective of Indigenous artists in New Mexico. In 1982, she co-founded the artist co-op Coup Marks to stage exhibitions of her fellow Native American artists. As a curator, she organised more than 30 exhibitions, the latest being the 2025 show at the Zimmerli Art Museum in New Brunswick, called Indigenous Identities: Here, Now & Always, with nearly 100 artists represented, including herself. There is a sense that she had much more to say and was enjoying being given bigger and more high-profile platforms, such as her 2023 retrospective Memory Map at the Whitney Museum of American Art, as well as this Fruitmarket show, before her death.

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith,

Montana Memories: Into the Dusk, 1989. Image courtesy of The Estate of Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Garth Greenan Gallery, New York and Stephen Friedman Gallery.

But what of the work? My first in-person encounter did not disappoint. The downstairs of Fruitmarket’s two-storey galleries shows the earlier works, including her 1988 Montana Memories series: thickly painted abstracts overlaid with some of the motifs that reappeared throughout her life – bowls, trees and horses. These works seem to give evidence of her long apprenticeship as a contemporary artist, absorbing inspirations from her peers of the 1960s and 70s. Some might see the influence of Robert Rauschenberg in the cardboard or newspaper clippings layered within the paint smears, and objects embedded on to the canvas – for example, a rusting saw in the 1990 painting The Forest (CS 1854), inspired by seeing the effects of acid rain on the Akwesasne Reservation. However, a catalogue essay by Lowery Stokes Sims shares Smith’s specific take on the warp and weft of inspiration, as being very much two-way. She quotes Smith from a 1982 interview in the Arizona Republic: “I look at line, form, colour, texture, in contemporary art as well as viewing old Indian artefacts the same way … A Hunkpapa drum becomes a Mark Rothko painting: ledger book symbols become Cy Twomblys; a Naskaspi bag is a Paul Klee; a Blackfoot robe, Agnes Martin; beadwork colour is Josef Albers; a parfleche is Frank Stella.”

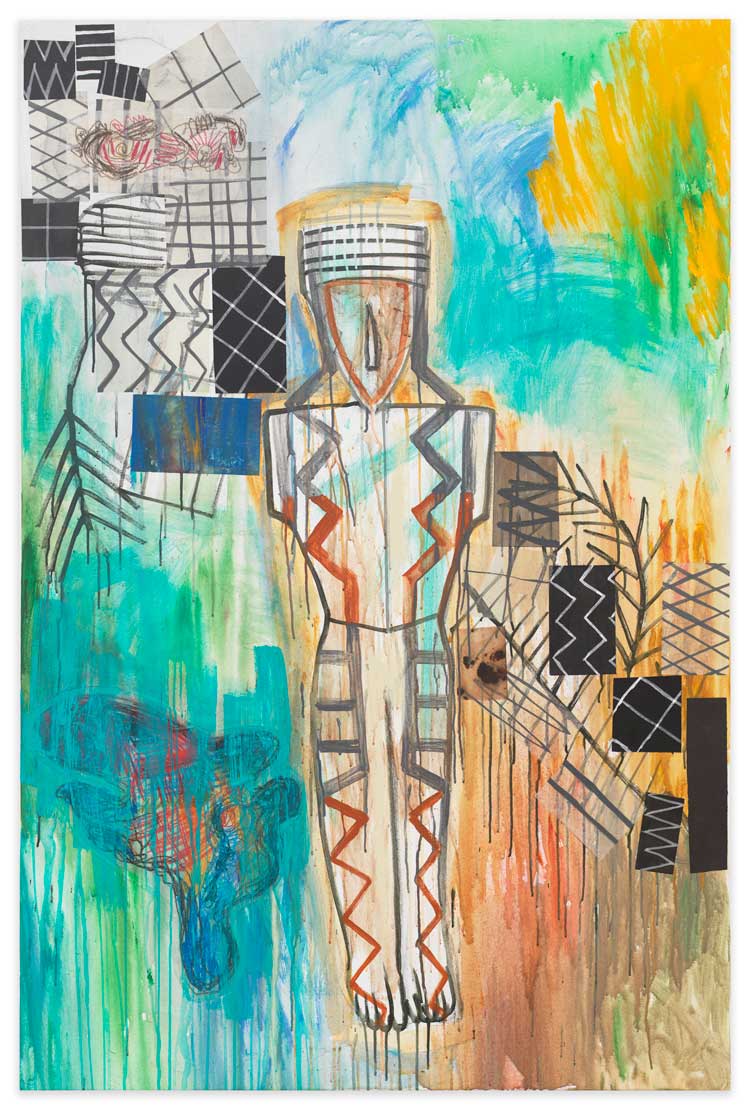

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, I See Red: Indian Drawing Lesson, 1993. Image courtesy of The Estate of Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Garth Greenan Gallery, New York and Stephen Friedman Gallery.

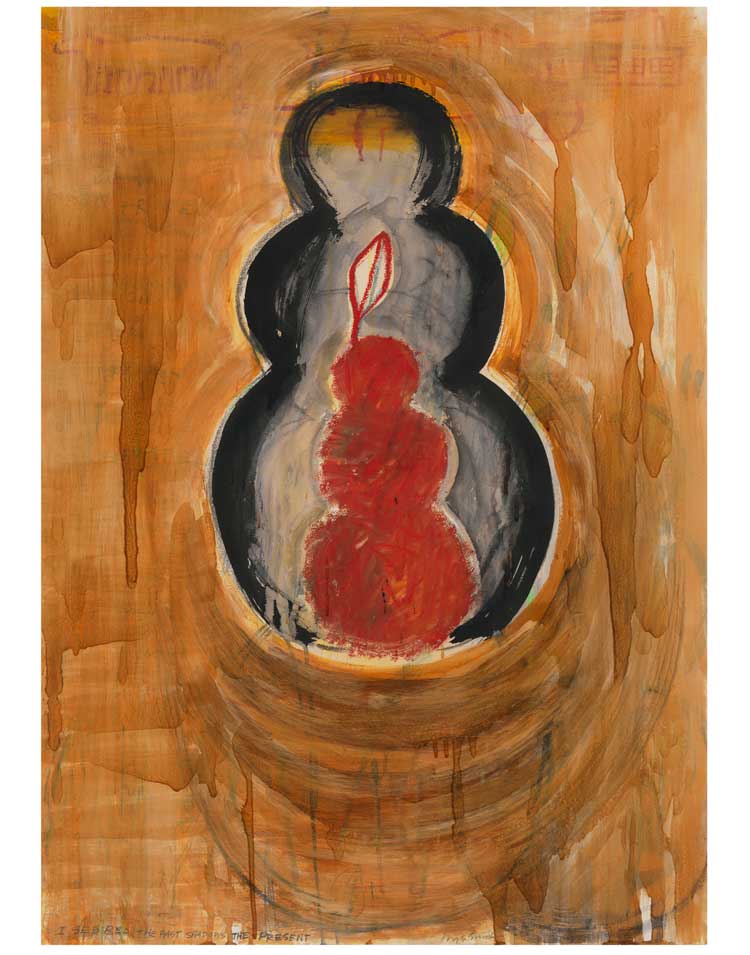

The use of motifs expands and evolves through her I See Red series from the 90s, several of which are also powerfully present. In I See Red: Indian Drawing Lesson (1993), there is a spirit of punky playfulness in which she mixes cartoon outlines with pictographs and petroglyphs, melding the ancient with the modern, humour and anger in a potent cross-fertilisation of symbols and signifiers that may (or may not) have a twist of Jean-Michel Basquiat. The outline of a snowman in I See Red: The Past Shadows the Present (1992) is inhabited by a smaller, red, “squaw” version, feather atop her head.

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, I See Red: The Past Shadows the Present, 1992. Image courtesy of The Estate of Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Garth Greenan Gallery, New York and Stephen Friedman Gallery.

The colour red is an enduring motif in her titles and her works. It represents anger, but she is also flagging up the demeaning “red Indian” term the colonisers applied to those whom they were robbing and displacing. It is also the colour of the earth, red ochre as a pigment for marking bodies and objects of significance.

,-1989.jpg)

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Red Cross (C.S. 1854), 1989. Image courtesy of The Estate of Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Garth Greenan Gallery, New York and Stephen Friedman Gallery.

Red appears, loaded with meaning, in the title of one of her most impactful paintings: Red Cross (CS 1854) (1989). Two lines of crushed and rusting metal cans form a crucifix, accompanied by a pendant of paint-smeared bobbins. Alongside them, the words: “All things of the Earth are connected”, taken from a speech attributed to Chief Seattle, a leader of the Duwamish and Suquamish peoples, representing the rights of his people and the land at negotiations in 1854 in the run up to the Treaty of Point Elliot the following year, hence the “CS 1854” in the title.

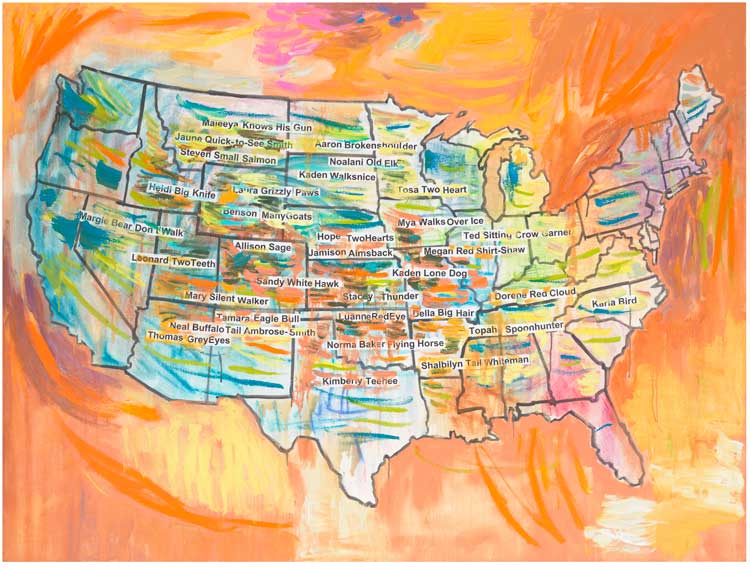

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, American Citizens Map, 2021. Collection Philip Holzer. Image courtesy of The Estate of Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Garth Greenan Gallery, New York and Stephen Friedman Gallery.

This work appears alongside three large and recent map paintings, on the room to the left of the entrance. A 2021 work American Citizens Map features the names of various of Smith’s Native American friends, plastered across each state to show the depth and spread of their presence. They include Thomas GreyEyes, Margie Bear Don’t Walk and Heidi Big Knife. Smith as well as her son, Neal Buffalo Tail Ambrose-Smith, also feature. The palette of joyful, rich and rainbow hues, dominated by orange, gives the work a celebratory feel.

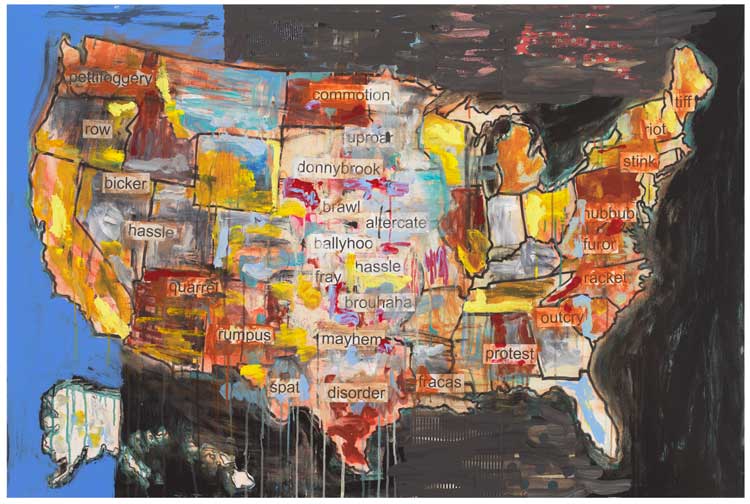

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, War is War, 2023. Private Collection, New York. Image courtesy of The Estate of Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Garth Greenan Gallery, New York and Stephen Friedman Gallery.

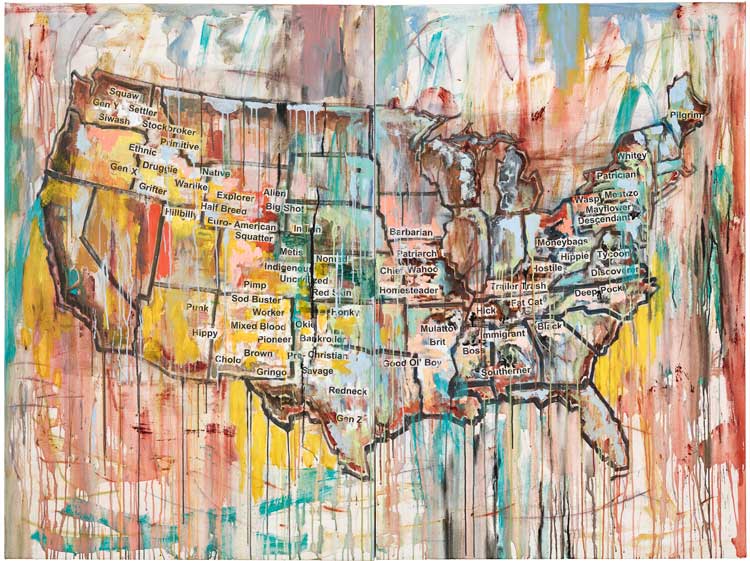

Not so with the map painting next to it. War is War (2023) is a far less harmonious affair. Muddy reds and blacks prevail, and dotted across the map are words such as pettifoggery, bicker, hassle, disorder and fracas. Next to it, also from 2023, is the American Slang Map. Here the words strewn across the continent include ethnic, druggie, half-breed and hillbilly, among other insults. The palette features dirty rainbow hues – a rainbow as reflected in a filthy, oily street puddle.

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, American Slang Map, 2023. Courtesy of Arte Collectum. Image courtesy of The Estate of Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Garth Greenan Gallery, New York and Stephen Friedman Gallery.

Smith once said that “landscape is never static”, but with these names she is establishing the presence of Indigenous Native American communities right across the map of the United States, and the ways in which they and other disenfranchised communities have been exploited and denigrated.

These works on the ground floor have a visceral intensity, the paint so lavishly and lovingly applied, scraped and reapplied. Smith’s intense, impassioned consciousness is vividly apparent in the whole – the layers of thought, the research and the references transmuted, along with her symbols, into something resonant and portentous.

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Tierra Madre: Robin Wall Kimmerer, 2024–25. Image courtesy of The Estate of Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Garth Greenan Gallery, New York and Stephen Friedman Gallery.

The upstairs works are lighter and more figurative. Some were made with the help of her artist son, as her health failed. We have several of her new Tierra Madre series, some made for this show, inspired by pioneering female environmentalists, scientists, artists, activists and humanists, whose work Smith admired. They include familiar figures such as the environmental advocate Rachel Carson, who first flagged up the devastation caused by pesticides in her 1962 book Silent Spring, and the botanist Robin Wall Kimmerer, director of the Centre for Native Peoples and the Environment at the State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry, and author of the books Braiding Sweetgrass and Gathering Moss, which have become seminal references for environmental artists and activists. Some are less familiar, such as Maria Sibylla Merian, a German entomologist who divorced her husband and set off with her daughter to Suriname in 1699 to study the rich insect life there. Smith told Bradley she was one of the first people to highlight the interconnectedness of nature, across all species, plants and land. She also used Native American names to identify plants. Her portrait includes pictograms of the plants, animals and people whose lives are dependent on that insect population.

Ambrose-Smith has shared that his mother’s inspiration for the “totem” style representation of these women was Keith Haring’s 1989 woodcut Totem, though she weaves her own distinctive magic into these portraits. In Sims’ catalogue essay, she spots that Smith “has deployed the linear elements on the surfaces of the bodies to interact with one another to suggest the outlines of additional forms, while creating a sense of an overall decorative scheme”. With those patterns, Sims says, Smith celebrates “global traditions of bodily design, from henna symbols to tattoos to scarification”.

These women stand with open arms, welcoming others to the community of those who pay attention to and respect the natural world. (There is an Annie Lennox figure, but sadly she wasn’t available for this show – a shame, as this feisty and outspoken Scottish singer and HIV/Aids activist would have made a natural national figure to celebrate here).

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith: Wilding, installation view, Fruitmarket, Edinburgh, 7 November 2025 – 1 February 2026.

There are also two big canoe works – canoes being one of Smith’s most frequently recurring objects. Bradley says: “She used the canoe … to signify the power of the artist to communicate across borders.” One is a physical canoe, drenched in red ochre, that hangs suspended over the staircase. Made with her son, the canoe is filled with hyper-realistic animals, apparently representing her family.

-Pic-V-Simpson.jpg)

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Trade Canoe: Turtle Island, 2024-25. Installation view, Fruitmarket, Edinburgh, 7 November 2025 – 1 February 2026. Photo: Veronica Simpson.

The other is a triptych at the far end of the gallery, called Trade Canoe: Turtle Island (2024-25). Turtle Island is a term taken from Native Americans mythologies about the creation of the American continent, describing a landmass forming on the back of a turtle. Writing in the catalogue, Lara M Evans (Cherokee Nation) says the canoe is “packed with all the things we need for survival, including reminders of the past, tools for the future, and the mistakes we hope never to repeat”.

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith: Wilding, installation view, Fruitmarket, Edinburgh, 7 November 2025 – 1 February 2026.

There is also an arrangement of some of Smith’s many drawings, framed and collaged across one wall in a vaguely fish-shaped formation. Coyote Stories Number 2 (1996-2025) followed by the smaller Coyote Stories Number 1 (1996-2025). Such an exuberant expression of her life and art, the irrepressible spirit with which she conjured thoughts, feelings and ideas: it is a fitting final flourish to an artist of enduring significance.

As Evans says: “In painting after painting, Smith explores ways to bring viewers to an understanding that is fundamentally not western, not colonial. It is a long, slow effort to indigenise cultural and political structures still steeped in colonial practices.”