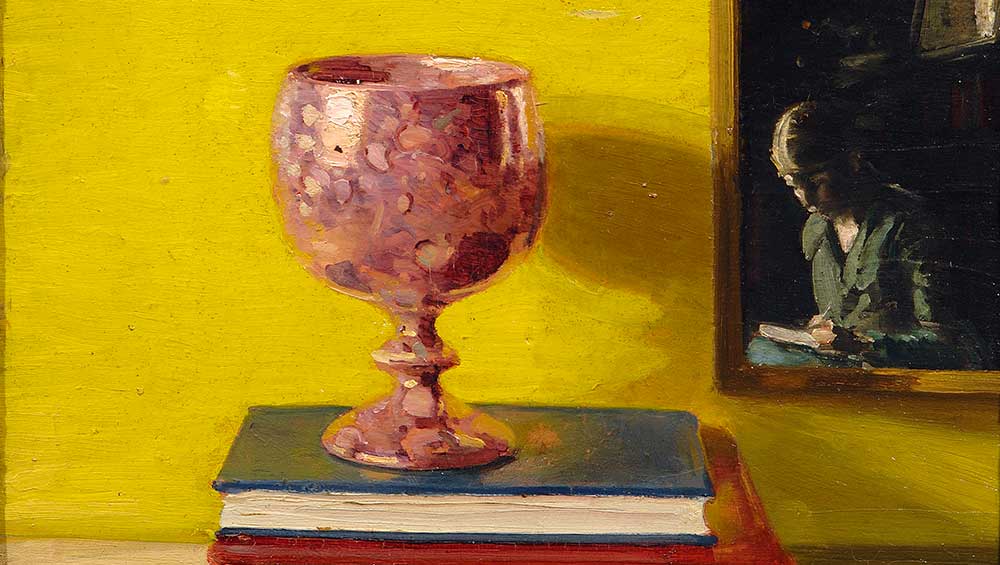

William Nicholson, Rose Lustre, 1920 (detail). Oil on panel, 27.5 x 33 cm. Private Collection c/o Hazlitt Holland-Hibbert.

Pallant House Gallery, Chichester

22 November 2025 – 10 May 2026

by DAVID TRIGG

He was a consummate portraitist, a masterful still-life painter and adept at depicting the English landscape. Furthermore, he was an accomplished graphic artist, book illustrator and theatre designer. William Nicholson (1872-1949), it seems, excelled at whatever he turned his hand to. The sheer breadth of his work, combined with the fact that he never aligned himself with any movement or group, means that his artistic vision is difficult to categorise. Consequently, he has sometimes been unfairly considered a minor artist, overshadowed by the success of his trailblazing son Ben Nicholson. In seeking to set the record straight, this magnificent exhibition at Pallant House Gallery – his first major show in 20 years – encompasses the British artist’s entire career, offering a panoramic view that showcases his extraordinary versatility across media and genres.

William Nicholson, The End of War, 1917. Lithograph on paper, Purchased by Pallant House Gallery (2024).

The loosely chronological exhibition opens with a selection of Nicholson’s graphic work, including the bold posters he produced between 1894 and 1899 in collaboration with his brother-in-law, James Pryde, under the name J & W Beggarstaff. To modern eyes, these simple designs for Rowntree’s cocoa and Kassama cornflour may not appear groundbreaking, but their flat colours and emphasis on outline and silhouette were considered radical in their time and likened to the work of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. More compelling is An Alphabet (1897), a series of 26 woodcuts created without Pryde, which features a motley band of Victorian characters ranging from B for Beggar (a nod to the Beggarstaffs) and D for Dandy, to G for Gentleman and V for Villain. To make the set more child-friendly, E for Executioner was later replaced by E for Earl. Nicholson himself appears in the very first image as a pavement artist: A was an Artist.

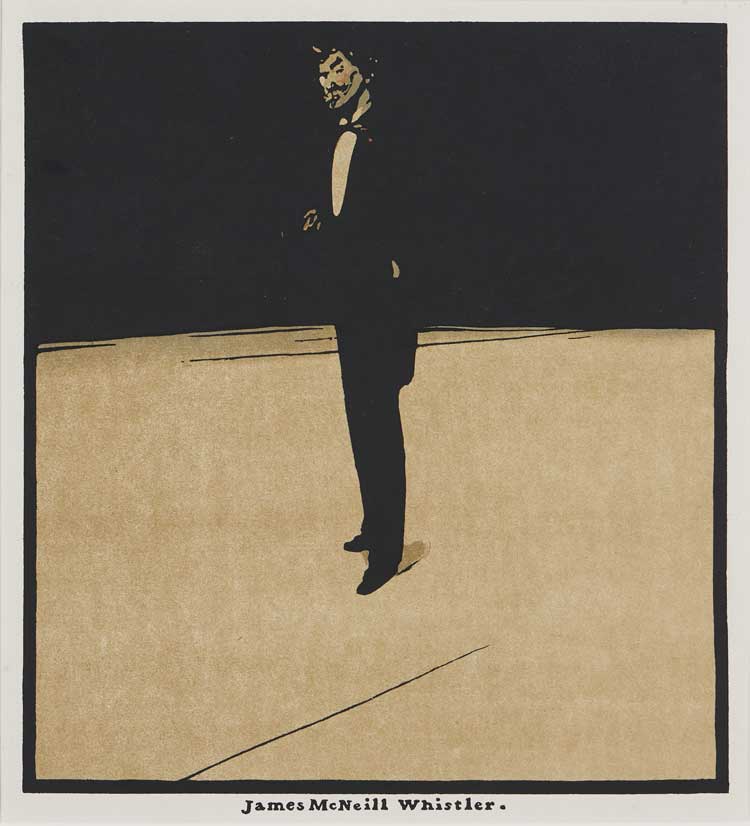

William Nicholson, James McNeill Whistler, 1897. Lithograph from the original woodblock, 24.5 x 22.5 cm. Muriel Wilson Bequest (2019).

After the death of Aubrey Beardsley in 1898, Nicholson was hailed as England’s foremost graphic printmaker, celebrated for his blocky and simplified style. His focus on the lives of ordinary men and women in series such as London Types (1898) gave his work wide appeal, while his iconic 1899 image of Queen Victoria walking with a cane and accompanied by a skye terrier became a bestseller despite the publisher William Heinemann describing the monarch as looking like “an animated tea-cosy”. He was also in demand as a book illustrator and designed covers for numerous publications, including David Dwight Wells’s Her Ladyship’s Elephant (1898), Siegfried Sassoon’s Memoirs of a Fox-Hunting Man (1929) and his own The Book of Blokes (1929). His illustrations also featured in much-loved children’s books, such as The Velveteen Rabbit (1922) and Clever Bill (1926).

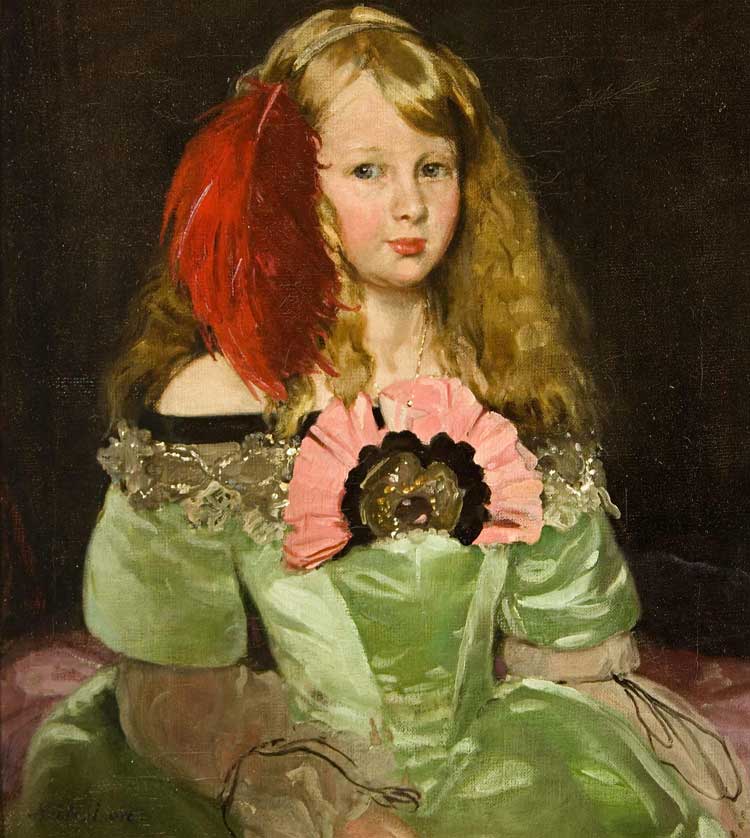

William Nicholson, Jennie as

Infanta, 1913. Oil on canvas, 58.5 x 55 cm.

From 1901, Nicholson shifted his attention from printmaking to painting. His portraits from the period display the same pared-down quality as his woodcuts, with well-known figures including JM Barrie and Max Beerbohm shown in profile and set against plain, tawny backgrounds. These somewhat staid compositions are countered by jaunty portraits of Edward “Feathers” Russell, the “Fool” of the Eynsham morris dancers who, unlike Nicholson’s society figures, would not historically have been the subject of a painted portrait. Nicholson made a decent living painting the great and good, but it is his non-commissioned pictures of people from lower social classes that steal the show here. In The Viceroy’s Orderly (1915), the imposing figure of Duffadar Valayat Shah, the colonial servant of Lord Hardinge, viceroy of India, is painted with great dignity, reflecting Nicholson’s respect for the humanity of his subjects, regardless of their standing in society.

.jpg)

William Nicholson, Nancy with Feather Hat (The Artist’s Daughter), 1910. Oil on canvas, 75 x 62.2 cm. Private collection, courtesy Richard Green Gallery, London.

Nicholson is revealed here as a sensitive painter of children and the show’s most endearing portrait, Nancy in a Feather Hat (1910), captures the artist’s young daughter in a magnificent ostrich-feather headpiece chosen from the dressing-up box in her father’s studio. Nearby, the unfinished and previously unseen 1901 portrait of his six-year-old son Ben is especially tender. The artist’s other sons, Christopher and Anthony, appear in a domestic family portrait from 1907 painted by William Orpen, who shared a studio with Nicholson. Orpen depicts his friend sitting at a dining table with his four children, while behind them a sense of domestic drama is suggested as the artist’s wife, Mable Pryde, reaches for the door handle. Nicholson’s dandified dress sense is evinced by his starched collar, yellow waistcoat, polka-dot dressing gown and polished black slippers.

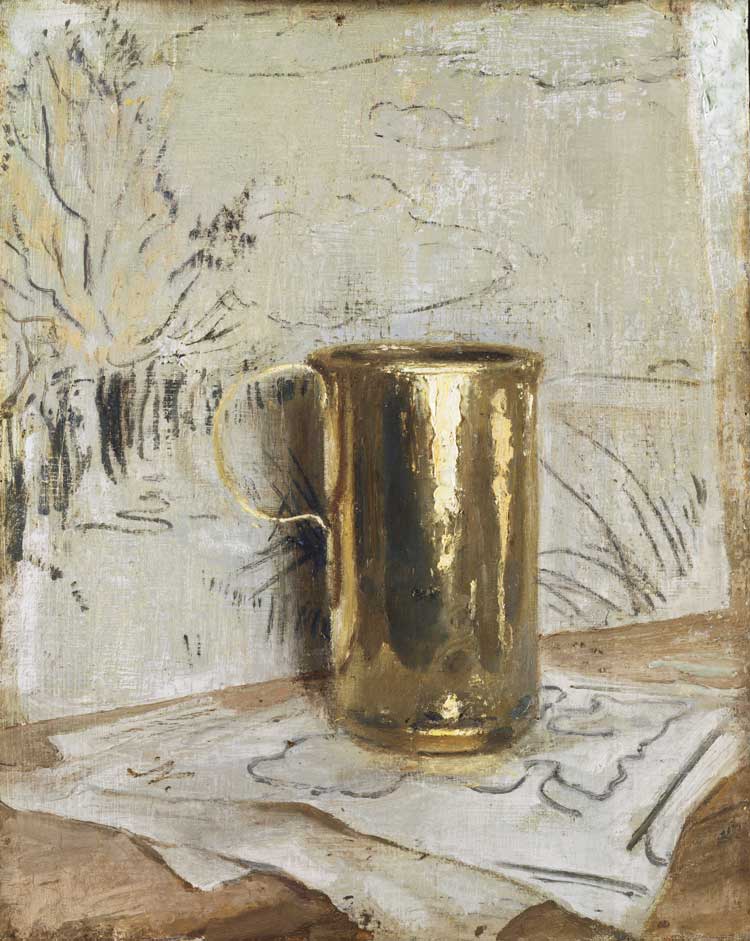

William Nicholson, Gold Jug, 1937. Oil on canvas board, 40.9 x 32.7 cm. Lent by His Majesty the King. © Royal Collection Enterprises Limited 2025. All Rights Reserved.

The contribution that Nicholson made to the still life genre in Britain cannot be understated. His exceptional skill in depicting everyday objects, especially the luminous qualities of glazed, polished and lustred surfaces, is seen in enchanting pictures such as The Lustre Bowl with Green Peas (1911), The Brass Canister (1917) and Gold Jug (1937), a favourite of the present Queen and loaned from the Royal Collection. Delightfully, The Silver Casket and Red Leather Box (1920), which was included in Pallant House’s The Shape of Things last year, is shown here alongside the actual tea caddy depicted – a creation of the 18th-century silversmith Hester Bateman (1709-94), whose silverware Nicholson collected. The valuable objects in so many of Nicholson’s still lifes find their antithesis in the wonderful Miss Jekyll’s Gardening Boots (1920), which immediately brings to mind the worn-out footwear of Van Gogh’s painting Shoes (1886). While the neighbouring portrait captures the likeness of the boots’ bespectacled owner, the garden designer Gertrude Jekyll, with painterly aplomb, this small still life conveys far more about her horticultural endeavours.

William Nicholson, Snow in the Horseshoe, 1927. Oil on canvas board, 32.5 x 40 cm. Private collection courtesy of Hazlitt Holland-Hibbert.

Nicholson similarly enjoyed the outdoors, and the countryside provided a welcome respite from London life. A keen walker, he often explored the chalk downlands of England, initially in Sussex and later in Wiltshire. With his portable paintbox and canvas boards he painted en plein air, capturing the interplay of light, tone and colour on the landscape. Compositions such as The Windmill, Brighton Downs (1910) and Snow in the Horseshoe (1927) are notable for their small scale and pared-down, almost abstract simplicity. Sometimes tiny figures are included, as with Cliffs at Rottingdean (1910) and A Glade Near Midhurst (1937), providing a sense of scale and emphasising the monumentality of the landscape. A room full of late landscapes, including paintings made in South Africa and Spain, emphasise Nicholson’s enduring love of the natural world as well as his evolving painting methods.

Nicholson hated the idea of being pigeonholed. In declining the invitation to be considered for election to the Royal Academy in the 1920s, he wrote to Alfred Munnings: “The idea of a label of any sort scares away from me all desire to paint.” It was an attitude that eventually led to his name being omitted from many accounts of modern British art, though it evidently afforded him a freedom of expression that he enjoyed to the full.