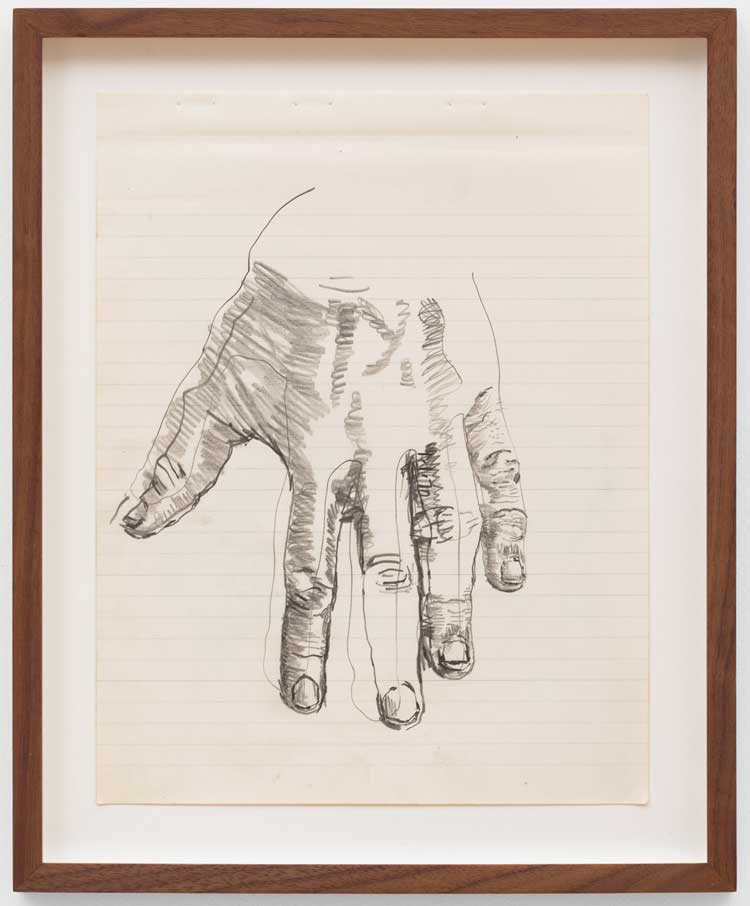

Paul Thek. Untitled, 1969-70. Pencil on paper, 27 x 21 cm (10 3/4 x 8 1/4 in) each. © Estate of Paul Thek. Courtesy of Pace Gallery, Galerie Buchholz, Mai 36 Galerie, and the Watermill Center, NY. Photo: Eva Herzog.

Thomas Dane Gallery, London

29 May – 2 August 2025

by JOE LLOYD

Paul Thek (1933-88) was forever painting windows. Seized by Joy: Paintings 1965-1988 features a showroom’s worth of glass panes. There are two small 1987 paintings that depict the wall of a New York apartment building from outside. In one, a shadowy figure can be glimpsed through the glass, though Thek does not reveal anything more. Other pieces show views of the city segmented into wide panels, and a teeming garden beheld through irregular lattice windows. One of the largest works on show, from 1972, features skyscrapers rising through a window painted on an otherwise almost empty canvas, so that the window frame exists independently of a wall and the world around it.

_ph-Ben-Westoby_Fine-Art-Documentation_01.jpg)

Paul Thek. Untitled (cityscape), 1972. Acrylic on canvas, 166 x 142 cm (65 1/4 x 56 in). © Estate of Paul Thek. Courtesy of Pace Gallery, Galerie Buchholz, Mai 36 Galerie, and the Watermill Center, NY. Photo: Ben Westoby / Fine Art Documentation.

Perhaps these endless sheets of glass indicate a knowing distance from the world, visible but separated. Such a status would certainly describe Thek’s relationship to the art world. He was a Brooklyn native who came up in the 60s New York art scene. His most exhibited works are the Technological Reliquaries (1964-67): wax sculptures that resembled dismembered limbs or raw chunks of flesh, often placed in Plexiglas boxes (one, from 1965, is in a Warhol Brillo box instead). The sculptures were inspired by seeing Jasper Johns’s wax works and the colour field squares of Josef Albers. He told Artforum: “I was amused with the idea of meat under Plexiglas because I thought it made fun of the scene – where the name of the game seemed to be ‘how cool can you be’ and ‘how refined’.” The large-scale The Tomb (1967) was a ziggurat encasing a pink effigy of Thek himself, with this right hand severed to leave a bloody stump, cordoned off like an archaeological site.

Paul Thek. Untitled, 1969-70. Pencil on paper, 27 x 21 cm (10 3/4 x 8 1/4 in). © Estate of Paul Thek. Courtesy of Pace Gallery, Galerie Buchholz, Mai 36 Galerie, and the Watermill Center, NY. Photo: Eva Herzog.

He was friends and then a partner of the photographer Peter Hujar, and appeared in about 20 of Hujar’s photographs; some of Thek’s work appeared in the recent Hujar retrospective at Raven Row in London. They travelled to Palermo together in 1963, where a visit to the Capuchin catacombs inspired them. Thek was close to Susan Sontag, and allegedly gave her the name for her collection of essays Against Interpretation, and was a subject of Andy Warhol’s Screen Tests. When Thek died from Aids-related illness in 1988, Sontag devoted her essay Aids and Its Metaphors to his memory. Otherwise, he faded from view. His paintings barely sold in his lifetime, and he spent periods unable to produce any work.

He has emerged from the shadows somewhat in recent years. In 2010, the Whitney Museum convened his inaugural north American retrospective. Seized by Joy is the first Thek exhibition in Britain in more than a decade. It was curated by fashion designer Jonathan Anderson and artist and writer Kenny Schachter, the latter of whom has written a volume on Thek and here exhibits some work from his own collection. They have displayed the pieces with a confidence that a more conventional curatorial duo might lack. In the gallery ’s front room, 10 of Thek’s cityscapes are huddled together around a corner, while a larger work with a similar subject matter dominates a facing wall. Infant-scaled chairs have been set out beneath these assemblages of work, perhaps implying that the works should be viewed from below, looked up at like altarpieces in a church.

_01.jpg)

Paul Thek. Untitled (rooftop water tower), 1983-84. Watercolour, chalk on paper, 46 x 61 cm (18 x 24 in). © Estate of Paul Thek. Courtesy of Pace Gallery, Galerie Buchholz, Mai 36 Galerie, and the Watermill Center, NY. Photo: Ben Westoby / Fine Art Documentation.

Considering the scope of Thek’s oeuvre today is difficult. Many works have vanished, including The Tomb. Thek himself did not help. In 1967, he moved to Europe where, as Matthew Israel writes in Art in America, he “embarked on the creation of stage-sized immersive environments” called Processions, which have been seen as predecessors of installation art. Many of these pioneering pieces are now lost. Thek used perishable materials (tissues, paper, sand) and would reuse objects from one piece to make another. He wanted art to be earthy and worldly, to reflect the place and time in which it was created. He said: “Just because, traditionally speaking, an artist is frequently the contemplative, removed from the world and devoting himself to an idealised and perfected image, doesn’t mean that art can’t be very much from the world as well.”

_ph-Ben-Westoby_Fine-Art-Documentation_01.jpg)

Paul Thek. Untitled (Grapes), 1974. Enamel on newspaper, 58 x 84 cm (22 3/4 x 33 in). © Estate of Paul Thek. Courtesy of Pace Gallery, Galerie Buchholz, Mai 36 Galerie, and the Watermill Center, NY. Photo: Ben Westoby / Fine Art Documentation.

This might seem at a remove from the window paintings, where Thek seems the very idea of the artist gazing at the world; or his diaphanous depictions of beaches and seascapes, with their cerulean skies, lapping waves and sunset glows. Yet these conventionally appealing landscape works feel more like the vigorous capturing of a moment than determined contemplations. Thek captures fleeting occurrences, such as a jogger running along the shore or a kite shivering in the wind. Like Johns before him, but with sparser means, Thek also signposts the materiality of his pairings. Some appear delineated within hand-drawn lines, stressing a sheet’s plain border. Like the objects of Processions, they exist on cheap, ephemeral material.

_ph-Ben-westoby_Fine-Art-Documentation_01.jpg)

Paul Thek. Untitled (Latin America), 1984. Oil on canvas, 61 x 91.5 cm (24 x 36 in). © Estate of Paul Thek. Courtesy of Pace Gallery, Galerie Buchholz, Mai 36 Galerie, and the Watermill Center, NY. Photo: Ben Westoby / Fine Art Documentation.

Many other paintings appear on top of newspapers, a practice Thek maintained on and off for the last two decades of his life. He began in 1969 after one of his trips to the Italian island of Ponza, where he fixated on water and solitary swimmers. Generally painted on to double-page spreads of the International Herald Tribune or the Village Voice, these works only partially efface the text and grids below. A 1973 diptych showing a pink-skied sunset over a rocky coastline floats above stories of Nixon borrowing a topcoat and an academy of music celebrating its birthday, as well as an advertisement for a home rowing machine. Thek contrasts this static, solid, grid-based order with the liquid, translucent, dynamic construction of his images. His fixation on clouds and waves, ever-moving forces of nature, seems a further kick against the structured surface below. Flatness begets depth.

_ph-Ben-Westoby_Fine-Art-Documentation_01.jpg)

Paul Thek. Untitled (South America), 1984. Acrylic on canvas board, 61 x 46 cm (24 x 18 in). © Estate of Paul Thek. Courtesy of Pace Gallery, Galerie Buchholz, Mai 36 Galerie, and the Watermill Center, NY. Photo: Ben Westoby / Fine Art Documentation.

These visions of water are the show’s highlight. They show a consummate draughtsman. Though they may seem to be far removed from his more provocative sculptural works, they share a similar resistance to refinement. Elsewhere in the exhibition, Anderson and Schachter display another aspect of Thek’s work, too – a strain of whimsy. One 1974 newspaper painting high up on a wall features a potato that has sprouted limbs over a field of blue; one from 1975 has two inverted hammer and sickles, albeit with the hammer replaced by an exclamation mark. Another section features four neat self-portraits on lined paper, which run the gamut from weariness to contentment. There are still many facets of Thek to discover.