-4.jpg)

Donald Locke: Resistant Forms, 2025. Installation view at Spike Island. Image courtesy the artist. Photo: Rob Harris.

Spike Island, Bristol

31 May – 7 September 2025

by DAVID TRIGG

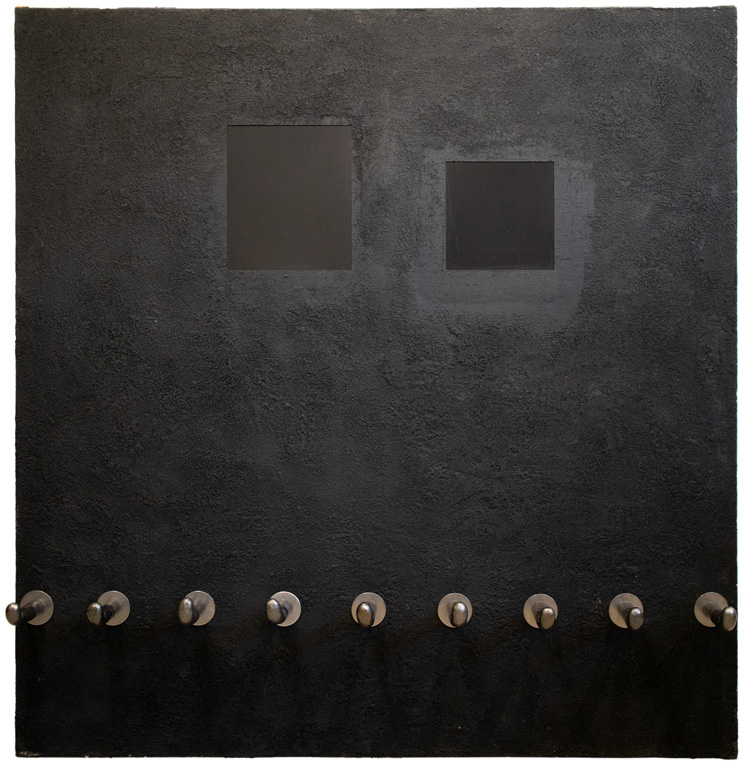

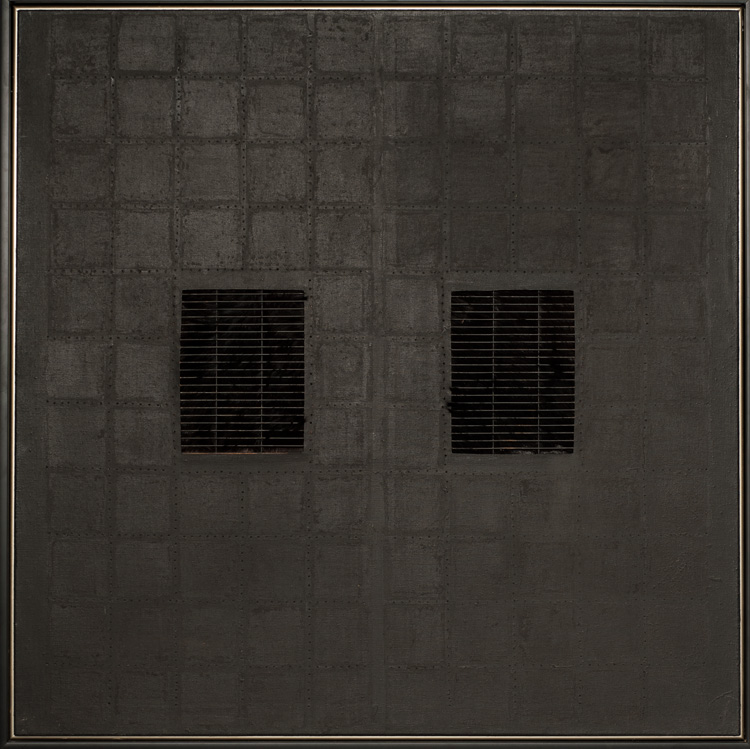

The three black monochrome canvases that open this exhibition are austere, aggressive and discomforting. Rows of sharp tacks protrude from their gridded surfaces, and one features a pair of carceral metal grilles. The Guyanese British artist Donald Locke (1930-2010) made these stark mixed-media works in the 1970s and, although they employ the language of geometric abstraction, they refer to the gridded topography of the Guyanese sugar plantations created by Dutch colonisers in the 16th century and later controlled by the British. In approximating aerial views of these sites, they point to landscapes that, to this day, are haunted by the scars of enslavement and indenture. Such melding of formal concerns with the dark histories of slavery and colonialism is characteristic of many works in this ambitious survey, which charts the development of Locke’s expansive, interdisciplinary practice from the mid-60s to the late 00s.

Donald Locke, Black Painting, 1978-79. Mixed media on canvas, formica, ceramic elements attached to canvas with stainless steel washers. Courtesy Estate of Donald Locke and Alison Jacques.

Born and raised in British Guiana (independent Guyana since 1966), Locke attended the Working People’s Art Class in Georgetown before receiving scholarships to study in the UK at Bath Academy of Art (1954-57) and Edinburgh College of Art (1959–64), where he became enamoured with ceramics. After relocating to Georgetown in 1964 to teach art at Queen’s College, a research bursary allowed him to return to Edinburgh in 1969 to further develop his ceramic skills, after which he moved to London, where he lived from 1970 to 1978.

The striking vessels and biomorphic volumes that Locke created during the 60s showcase his versatility and expressive freedom as a ceramicist. Shaking off the rigid limitations of mid-century British studio pottery, they are a celebration of clay, evoking the human body and organic forms. These sensual, tactile pieces paved the way for his radical Plantation Series (c1972-6), in which ceramic elements are combined with metal, wood, grass, carpet, fur, paint and lacquer to directly address themes of subjugation in colonial Guyana. With a practice increasingly unbounded by geography and the conventions of British art, this development flowed from Locke’s diasporic identity. As he remarked in a 1976 interview, he was now working “without the old inhibitions which still operate with deadening effect in many of the studios in Britain”.

-13.jpg)

Donald Locke: Resistant Forms, 2025. Installation view at Spike Island. Image courtesy the artist. Photo: Rob Harris.

The small assemblages Plantation K-140 (1974) and Plantation Piece (1973) comprise black, rectangular bases topped with tight rows of slender ceramic forms. Alluding to human figures, these vertical protuberances are held by small metal cages, a reference to the devices designed to trap fruit-eating pests on Guyanese plantations but also suggestive of those used in the enslavement of people. Although they were initially presented as purely abstract sculptures, Locke would later concede that these works were metaphors for the coerced labour of the exploitative plantation system that shaped Guyana and other Caribbean nations. As he said in a 2007 interview, his use of formalist abstraction was a way of refracting his predominant interest in “the nature and experience of the black man in the New World”.

-5.jpg)

Donald Locke: Resistant Forms, 2025. Installation view at Spike Island. Image courtesy the artist. Photo: Rob Harris.

The most well-known work in the exhibition, Trophies of Empire (1972-74), is a large open shelving unit with 27 compartments, each housing one of Locke’s infamous ceramic “bullets”. Some of these highly polished black cylinders appear like candles, while others resemble cucumbers, erect stamens (à la Robert Mapplethorpe) and, somewhat inevitably, phalluses. Indeed, critics have consistently read them as priapic forms. Rasheed Araeen, writing in the catalogue to the seminal exhibition The Other Story at the Hayward Gallery in 1989, suggested that Locke should “come out of the cocoon of his sexual fantasies and come to terms with the outside world”. However, the artist always maintained that these objects, which are mounted into trophy cups, candle holders, and other assorted vessels, were ammunition.

Donald Locke: Resistant Forms, 2025. Installation view at Spike Island. Image courtesy the artist. Photo: Rob Harris.

Such ambiguities typify Locke’s works. A case in point are his mixed-media canvases of the 90s, made after a Guggenheim Fellowship brought him to the United States in 1979 (he first lived in Phoenix, Arizona, until 1990, and then Atlanta, Georgia, until his death). Their surfaces contain expanses of black paint applied with wild, gestural brushstrokes and overlaid with perplexing amalgamations of found objects and photographs. Pieces of wood, metal and fur collide with photographs and photocopied images of, among other things, Confederate and Union soldiers, the British royal family, weapons and Locke’s own sculptures, including bronzes made in Arizona such as Pomona Blue (1985-86) – a voluptuous female figure without arms, feet or a head, inspired by the tragic story of the 19th-century enslaved woman Sarah Baartman.

These works are as much about the artist’s enjoyment of assembling disparate materials as they are commentaries on plantation violence, colonial injustices and the history of American racial politics. With them, Locke aligned himself with a lineage of 20th-century artists working with assemblage, from André Breton to Robert Rauschenberg, to black vernacular artists of the American south such as Thornton Dial and Lonnie Holley. In doing so, he ensured that they remained open to a multiplicity of readings.

Donald Locke, Southern Mansions, 1996. Ceramic, wood, artificial fur. Courtesy Estate of Donald Locke and Alison Jacques.

Marking the apex of his mixed-media paintings are the powerful, large-scale canvases The Mark of Brer Nancy (1995) and Southern Mansions (1996), both of which feature striking bursts of colour, most notably slashes of blood-red paint that emerge like flesh wounds from beneath layers of thick black paint. On each painting, partially obscured by dark clouds of pigment, are spectral images of antebellum plantation houses and Locke’s past works, including his ceramics and Plantation Series. Southern Mansions is punctuated by what look like whips as well as several square, velvet-lined recesses – pitch black cavities that recall Kazimir Malevich’s suprematist geometry and which introduce an incongruous sense of orderliness amid the painterly tumult and evocations of violence.

Donald Locke, The Cage, 1976-79. Acrylic on layered canvas, steel, fur. Collection of Lorenzo Legarda Leviste and Fahad Mayet.

Locke’s immersion in Atlanta and the American south had a huge impact on the direction of his late work. It was also a period of looking back; he returned to mixed media ceramics; to Guyanese folklore in his charcoal drawings; to figuration in the decoration of ceramic vessels; and he revisited pivotal works, as in Trophies of Empire #2: The Cabinet of Billy Mick Miller (The Altar Piece of Hernando Cortez) (2006-08), in which the ceramic bullets of the original are replaced with improvised sculptures and talismanic objects made from found objects, scrap wood, and locks of human hair. Reminiscent of ethnographic displays, this second iteration is a wunderkammer of sorts, bringing together aspects of African American vernacular art, Caribbean mythology and reflections on Locke’s journey as an international artist.

Speaking to Locke’s ideas about the hybridity of black culture and its contributions to modernity, Trophies of Empire #2 is characteristically rooted in diasporic reflection, material inquiry and oblique social commentary. As with so many works in this long overdue exhibition, it is multilayered, complex and idiosyncratic, inviting subjective readings and eschewing singular interpretations. This appears to have been a deliberate tactic on Locke’s part. It is what makes his works so baffling and yet, at the same time, consistently intriguing and richly compelling. In mining his personal history as well as the colonial legacies of the countries in which he resided, Locke made a vital contribution to art history, one which can no longer be overlooked.

Donald Lock: Resistant Forms will tour to Ikon Gallery, Birmingham, 1 October 2025 to 22 February 2026; and Camden Art Centre, London, 3 April to 6 September 2026.