Lucy Stein, Wet Room, 2021. Installation view, Spike Island, Bristol. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Gregor Staiger, Zurich. Photo: Max McClure.

Spike Island, Bristol

25 September 2021 – 16 January 2022

by JANET McKENZIE

The first major solo exhibition in the UK by the Cornwall-based artist Lucy Stein is presented by Spike Island in Bristol. Stein’s painting is informed by conceptual art practice, her own performance art over 15 years and her study of psychoanalysis and feminist theory. As an obsessive maker and prescient observer of contemporary culture, she also has a passion for esoteric and mystic philosophy and the rich local history in Cornwall, where she has lived at St Just, since 2015. In March last year, as the pandemic spread, her second daughter was born. The experiences have given her painting a visionary power in the present climate of global fear and disaster. Stein’s long-term identification with mystical thought, with goddess culture and witchcraft has empowered an existing love of painting.

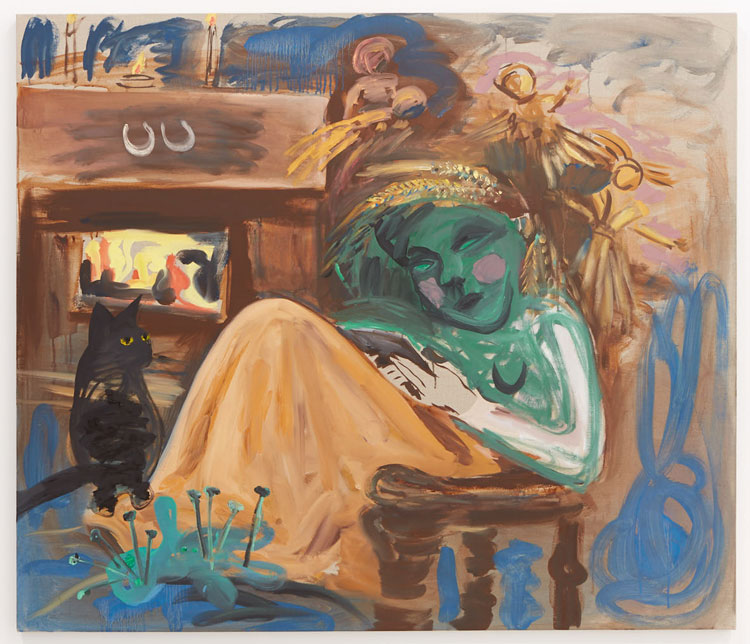

Lucy Stein, The corn goddess goes back on Instagram, 2021. Oil on linen. Installation view, Wet Room, Spike Island, Bristol. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Gregor Staiger, Zurich. Photo: Max McClure.

The notion of conceptual painting as a 21st-century phenomenon came up in conversation with Stein (b1979), whom I first interviewed for Studio International in 2009, soon after reviewing Tal R. “Conceptual painting” in this context refers to the importance of the inheritance of the alchemical vision of Joseph Beuys, his creative processes most evident in his drawing and his description of it. Of course, there are many other instances of conceptual artists who have informed the artist in the 21st century, consciously to express and explore deeply felt experiences yet contextualise them within the universal and within art history and theory. Perhaps all conceptual painting is underpinned by a fluid drawing practice? It is the immediacy of drawing fused with a visceral power of colour, informed as it is with the conceptual inheritance of non-object art that marks the best painters working today. Multifaceted in conception, painting in the present allows the expression of the ephemeral and deeply subjective aspects of life in a non-prescriptive, non-academic form. Contradiction for Stein is an essential part of art-making in the present as opposed to conservative figuration, with a commitment to ideas.

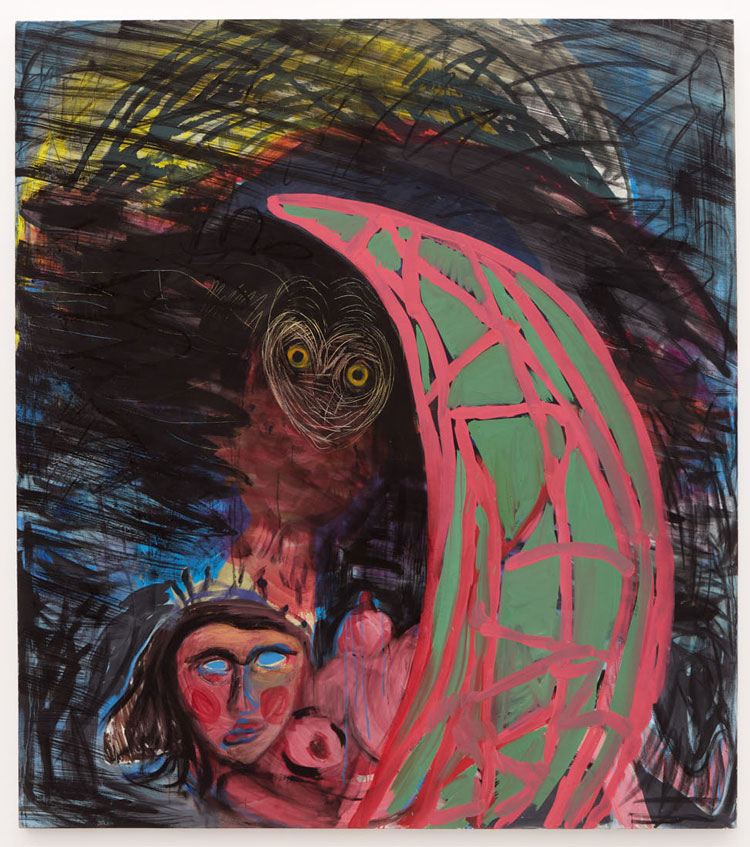

Lucy Stein, Erotic encounters South West, 2020. Acrylic, oil, charcoal on canvas. Installation view, Wet Room, Spike Island, Bristol. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Gregor Staiger, Zurich. Photo: Max McClure.

The experiential in Stein’s new paintings and drawings at Spike Island, in this case childbirth – a visceral, challenging experience in the best of circumstances but in this instance compromised by lockdown protocols (no partner allowed at hospital births) – followed by the hour-by-hour requirements of new motherhood, has perhaps given an uncompromised passion and focus to her most recent body of work. Her rigorous training in drawing at Glasgow School of Art with the conceptual training (under Marlene Dumas at De Ateliers, Amsterdam) have come together with her pandemic experience to great effect. She has exhibited in the UK and abroad. The list of exhibition titles indicates her serious intent and her wit: On Celticity 2016; Fuck You where’s my Suger, a two-day festival on themes of depression and hysteria that she co-organised with Mark Harwood, 2017; and Neo-Pagan Bitch-Witch, London with France-Lise McGurn, 2016). Between November 2019 and May 2022, Stein and Sarah Hartnett are undertaking a pilgrimage along the Mary ley line, which runs from Carn Lês Boel in Cornwall, to Hopton in Norfolk.

Left: Lucy Stein, Sylv’s first bath, 2021. Oil on canvas; Right: Lucy Stein, Hag Fight, 2020. Oil on canvas. Installation view, Wet Room, Spike Island, Bristol. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Gregor Staiger, Zurich. Photo: Max McClure.

The divine energy in Stein’s new work produced in lockdown is tantamount to a call to arms while governments are failing to recognise the cultural necessity of art and the importance of individual creativity for personal wellbeing and a healthy society. Stein transforms quotidian rituals of nurturing new life with the historic importance of water, and the necessity of a female world in tapping the power and mystery of the earth’s capacity to renew.

Lucy Stein. May Queen, 2021. Oil, wax resist, charcoal, Sennelier pastel on linen. Installation view, Wet Room, Spike Island, Bristol. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Gregor Staiger, Zurich. Photo: Max McClure.

Cornwall’s history is replete with dualities: mining industries and Methodism, surfing, tourism and esoteric culture. Historically, it is rich culture, where the myriad of monuments can act as triggers for a personal pilgrimage, for spiritual and artistic journeys. In her essay to mark the Spike Island exhibition, Amy Hale conjures the cultural significance of the artist’s foray into an ancient world: “Here we tell stories of women who wander, of women encountering the land, creating new narratives of wonder, curiosity, challenge. In [one of Stein’s sources] The Chaldean Oracles, Hecate is the soul of matter, feminine in essence, infusing the material with the hot breath of life. She is also a Goddess of Witchcraft and the underworld.” Hale cites Ithell Colquhoun’s The Living Stones; Cornwall, (1957) as making reference to “Fountains of Hecate” where Earth’s energies are most potent. For millennia, humans have marked these sites in various ways, primarily with stone monuments. Mystical philosophers interpret the practice as, “indicating points of subterranean power, enchanted not only by their proximity to underground currents, but also by the rites conducted in and near them. These rites are not only an acknowledgement of their power, they are a gift of force in return that refreshes them in a continual flow.”

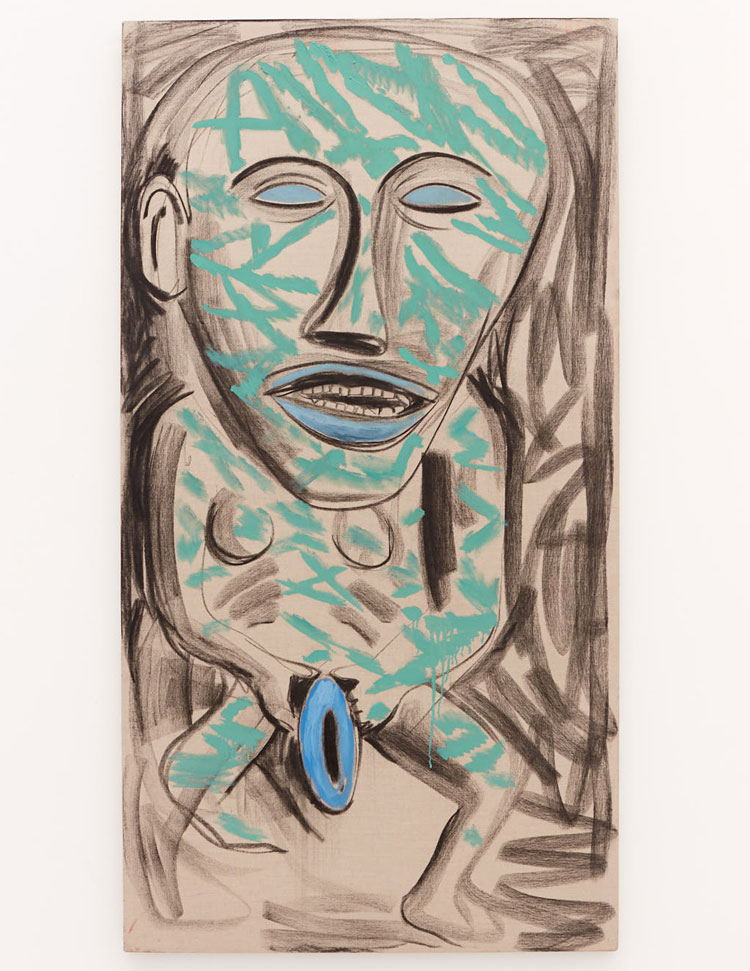

Lucy Stein. Self portrait as a Celtic Sheela, 2020. Charcoal and oil on linen. Installation view, Wet Room, Spike Island, Bristol. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Gregor Staiger, Zurich. Photo: Max McClure.

As her point of departure, Stein chose the fougou – narrow neolithic underground passages unique to west Cornwall that lead to womb-like chambers that have become sacred sites of worship and are thought to have been used in ritual rebirthing ceremonies – to explore the long history of the female. Wet Room centres on an installation comprising a bathtub and sink with running taps, surrounded by tiled walls with hand-painted sea creatures and mermaids that explore esoteric cultures such as the Celtic goddess culture of Land’s End.

Lucy Stein, Wet Room, 2021. Installation view, Spike Island, Bristol. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Gregor Staiger, Zurich. Photo: Max McClure.

Wet Room is the culmination of years of work using the landscape as her site-specific tableau. She researched goddess culture at Cornwall’s Museum of Witchcraft and by “hanging out with the Penzance pagans”. She says: “I have been literally possessed by ideas of enchantment.” The female body represents centuries-long beliefs that pertain to fertility. The works are personalised and thus intensified by the use of what the artist refers to as “raw painting”, the performative ritual of which, enables her to unveil her vulnerability. Stein says that childbirth and the daily care of her new baby and her other daughter have given her strength through being needed: “I consider it a privilege within what is a culture of entitlement where artists are only the content providers for capitalism. It’s a big relief that I’m able to live my life as a ‘creative’, but I don’t think that being an artist should be viewed as a privilege. As is the case in good parenting, doling out love and initiating atmospheres of enchantment makes the world more bearable, but it takes a lot of energy. Artists are content providers for capitalism, yet we’re constantly told that what we do is not real work. I reject that with every bone in my body and see it as another facet of ‘the gentrification of the mind’. This mindset developed alongside the ‘airportisation’ of social space and occupies us ruthlessly. What is useful and necessary is relegated and what is frivolous is promoted. Good art is not a luxury, or a privilege nor is it frivolous although it can appropriate all of these modes to get its message across.”

Lucy Stein, Wet Room, 2021. Installation view, Spike Island, Bristol. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Gregor Staiger, Zurich. Photo: Max McClure.

In 2009, Stein’s show at Gimpel Fils, Creemie Myopic Fables, challenged the pervasive visual stereotypes of raunch culture, addressing issues of female sexuality in post-feminist culture. Her recent work continues to depict a wide range of western female archetypes: a mournful Mary Magdalene (2021) kisses the wounds of a dead Christ; a vivacious May Queen (2020) with exaggerated breasts holds an ear of corn and the outrageous and funny, Hag Fight (2020) presents a brawling, half-naked old woman.

Lucy Stein. Splitting and projection, 2020. Wax resist, poster paint, oil on linen. Installation view, Wet Room, Spike Island, Bristol. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Gregor Staiger, Zurich. Photo: Max McClure.

Splitting and Projection (2020) embodies and illustrates the psychoanalytical processes that Stein is studying. The method employed includes the application of wax to unpainted linen to resist the oil paint. A multiplicity of images is thus constructed, a skeleton split in two is suspended against a vigorously painted red background and surrounded by ghostly traces of other figures.

Looking at El Sol (2021), I am reminded of Ken Kiff, whose marvellous and haunting works I often return to and am never disappointed. They are enigmatic within an imaginary world that is quintessentially human. His use of bare canvas or paper endows the work with a spiritual, numinous quality. El Sol is created with the vigorous application of marks and layering that conjure an inner world such as that created by Kiff. Where Kiff and his generation spoke relatively little about his own practice, Stein and her peers do not have the option to say nothing of where their work has evolved from, its conceptual base. When I mentioned Kiff in the context of describing her work as conceptual painting, Stein told me she loves Kiff. “I travelled to Norwich with my husband and new baby daughter to see that show in 2019. I wish I left more bare canvas in my works, but he really has helped me to leave any at all. We have his illustrated folk tales of the British Isles at home, and I refer to them often. It was also important for me to use unpainted (non-white) linen as a small gesture of decolonisation, that white should not be the ground upon which the whole theatre of making paintings plays out. I think conceptual art and performance art are internalised by painters now, and every gesture, however theatrical or passive, is in relation to this expanded field.

Lucy Stein, Baubo, 2021. Crysta Soap Base, Port Navis Oyster shell (crushed), Princes gay dahlia petals, Autumn Equinox, Oakmoss, Clary Sage, Geranium Egypt ointments. Installation view, Wet Room, Spike Island, Bristol. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Gregor Staiger, Zurich. Photo: Max McClure.

“Psychoanalytic theory with all the stripping down and dissection of layered complexities that it entails, whichever angle you take it, is to me is the most generative system to think about painting through. I suppose that implies that the painting encompasses the spirit, the body and the text. (Everything in psychoanalysis is triangulated.) Also, the idea of the numinous and how this can relate to more 20th-century ideas of presence and absence, and the gestalt, in painting and other mediums is a productive lens for me. It allows for despair and hubris and all the other woman-alone-with-herself feelings that rise up when I paint. Just the word ‘medium’ gets activated when you look at the creative process through that lens, although this is only one angle of many from which to tackle the problem of painting. The course I did in 2020 with the SITE South West in psychotherapy totally opened my mind and revivified the whole process for me.”

• Lucy Stein: Wet Room is commissioned and produced by Spike Island, Bristol. The exhibition tours to De La Warr Pavilion, Bexhill-on-Sea, from 29 January to 2 May 2022.