Céline Condorelli, Dedication (To The Sea, To The Sea). Folkestone Triennial, 2025. Photo: Lia Toby/PA Media Assignments.

Various venues, Folkestone, Kent

19 July – 19 October 2025

by VERONICA SIMPSON

It is fitting that Sorcha Carey’s first outing as curator of the Folkestone Triennial is called How Lies the Land? Her predecessor, Lewis Biggs, across three triennials, cultivated often inspiring and bravura performances, expressions of each artists’ characteristic style and materials, which detonated across the town- and sea-scape – often chiming with the social or economic issues of the town or of the day, but not consistently. By comparison, Carey’s choreography of 18 artworks, by artists from 15 countries, is a subtler, deeper, and, for me, cumulatively more powerful dialogue with this distinctive coastal terrain. A common thread across almost all the works is an intensity of focus and attention to the ground beneath our feet, the plants, the birds above us, the various bodies of water that surround us, and the impacts of climate and human activity on this ever-shifting and eroding location.

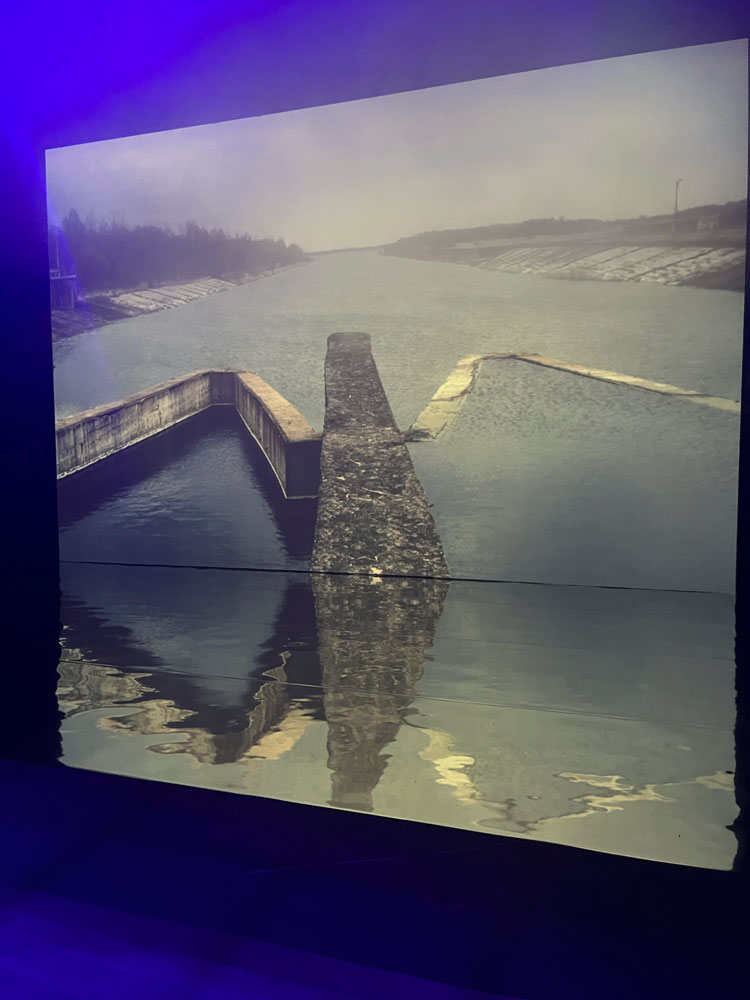

Descending from the first floor bar at the Quarterhouse, the main gathering space for Folkestone’s creatives and visiting culture lovers, you enter a darkened room. Here, a massive screen is showing the Lithuanian artist Emilija Škarnulytė’s film Burial (2025), the almost monochrome tones of which are reflected in the large, silvery floor tiles placed immediately in front of it. In the film, she poses profound questions about what happens when we harness science to mess with nature – in this case, using atomic energy to power our lives – and how we deal with the consequences. Burial is a mesmerising, hour-long meditation on the slow dismantling of Lithuania’s Ignalina nuclear power plant, which was decommissioned in 2009 and is still, slowly, being taken apart.

Emilija Škarnulytė's film Burial. Installation view, Folkestone Triennial, 2025. Photo: Veronica Simpson.

As we see the workers in their hazmat suits painstakingly dismantling elements of this huge nuclear energy plant – sister to Chornobyl, it was fitted with the same Russian RBMK reactors, and thus its decommissioning was a condition of Lithuania joining the EU – we are invited to hold two conflicting notions in our heads: an awareness of the radioactive toxicity of these components (nuclear waste, as far as we know, can take hundreds of thousands of years to deactivate) and the fact that the containers designed to keep the radioactive components (and us) safe are only good for the next 100 or so years.

Stylistically, the film bears the influence of Andrei Tarkovsky, but Škarnulytė weaves her own languorous, nihilistic spell with the pacing. Filmed with her team over three years of staggered visits, the camera lingers over this monolithic building, its epic infrastructure, from the cooling towers stacked (but still lethal) in a sealed bay to the ornate, graphic arrangement of its 20th-century control panels (now inactive). She adds layers of her own mythological symbolism through closeups of sensual, slithering snakes – Burmese pythons, in this case. Why snakes? She says: “It’s about not having the story just from the human perspective.” After visiting several nuclear sites, “where there are no humans left, but nature and animals have taken over,” she likes the use of pythons for their pagan reference by which they are known in Lithuania – as a symbol of rebirth.

Škarnulytė’s grandmother was apparently blinded by a nuclear cloud in 1986, the year before Emilija was born, and as a result, the artist tells us, her grandmother has never seen her face. No wonder then that Škarnulytė says: “I am fascinated by borders you can’t see.”

Sarah Wood, Prospect. Folkestone Triennial, 2025. Photo: Thierry Bal.

There are multiple connections between the works Carey has picked – unlike Biggs’s more liquorice allsorts approach. Just around the corner from the Quarterhouse is a small beach hut by Sarah Wood, its blackened timber and rusting tools in the entrance evoking Derek Jarman’s famous Prospect Cottage, half an hour’s drive east along the seafront. Jarman was attracted to the bleak poetry of this stretch of unusual, desert landscape, not least for the presence of Dungeness power station, right up against the water. He bought Prospect Cottage in 1986 after being diagnosed with HIV, and that sense of a body at war with itself, while finding beauty in the resilience of this semi wilderness, and the garden he cultivated, is tangible in the clips Wood has pieced together. Her film, which she also titles Prospect, collages home movies from Jarman’s archive with unused footage for his film The Garden, over which she has laid her own imagined conversation with the artist and his inspirational influence, his rallying-cry for beauty, nature and community.

There is also a harmonious cluster of works side by side on Folkestone’s East Cliff. Katie Paterson’s Afterlife (2025), an ode to amulets, in a semi-ruined Martello Tower sits next to Jennifer Tee’s Oceans Tree of Life, a seaweed shaped earth work, the russet limbs of which sprawl across the grass to the cliff edge, overlooked by Urn Field, Sara Trillo’s sun-baked, giant vessels of compacted local clay and herbs. I have not seen such sympathetic adjacencies demonstrated before at Folkestone, nor so well at most public art festivals. And they enjoy the additional frisson of being set either side of an active archaeological dig.

Katie Paterson, Afterlife. Folkestone Triennial, 2025. Photo: Lia Toby/PA Media Assignments.

Paterson’s contemplations of time and matter are always richly rewarding. Afterlife (2025) is no exception. The circular contours of the brick Martello tower perfectly accommodate a pale, curved wooden table into which Paterson has inserted 197 replicas of different amulets, gathered over the last three years. Drawing from ancient history, from Mesopotamia to modernity, and from cultures all over the world, from Africa to Asia and the Americas, these amulets – which traditionally offered protection to their owners, whether carried on journeys or buried alongside them – have been sourced from a multitude of individuals and institutions, digitally copied, 3D printed, and then used to mould a new amulet, formed from significant materials, such as bark from mangrove swamps, or microplastics found in a snowball taken from Mount Everest, which are then ground down to provide materials for the casting.

Zeller & Moye, a Berlin-based architecture and design studio that Paterson has worked with before, has designed this delightful display table, with each hollow and channel shaped to accommodate specific amulets, while echoing the contours of a riverbed. Without this table, the collection would not sing half as sweetly. Gazing at each item, from a netsuke mouse to an Egyptian ankh, or key of life symbol, their forms and textures are offset beautifully by the soft, buttery, tones and materiality of this sycamore wood: these are objects to be cupped in the hand or worn close to the body, says each bespoke, undulating contour. And the experience is all the better for the objects not being protected under glass.

The amulets are arranged not chronologically but according to the types of landscape in which they were found, as well as the human actions causing their erosion (pollution, war, extraction). All the finds and materials are itemised in an elegant leaflet, available to visitors. Paterson says the work involved has “been the equivalent of making 197 sculptures – just because they’re tiny it makes no difference. It’s a huge number of donations. There’s a huge list at the back (of the leaflet) of people who have helped or donated materials – everyone from Unesco to the Antarctic Survey.” She declares herself “done” with amulets, not because the amulets are in any way boring, but because the materials sourced to make them were “so contentious and challenging. There’s coral from bleached islands. Glaciers that are now gone completely. Or rainforests that will be gone in our lifetime. It’s really tough things. But visually I love them all. I am absolutely hooked on amulets,” she says. This work will also be shown later this year, in the splendid circular observatory tower in Edinburgh’s Collective gallery, of which Carey is a director.

Jennifer Tee, Oceans Tree of Life. Folkestone Triennial, 2025. Photo: Veronica Simpson.

A short walk up a grassy slope from the tower brings us to Tee’s Oceans Tree of Life, which draws inspiration from Rachel Carson’s The Edge of the Sea, published in 1955, in which Carson outlined the interdependencies of plant and animal life in the intertidal zone. Tee has embedded her large seaweed form into the grassy clifftop above Folkestone Warren, where the beach is rich in fossils. The work comprises a series of snaking pathways formed by hand-cast bricks, in colours chosen to reflect the white chalk in the cliffs and the reds, greens and browns found in seaweed. Each brick is embossed with images showing different species of kelp or extinct creatures and some of these embellishments have been fired with glass made from ground sea glass. This work could well be a “keeper” – there is some leeway for the citizens of Folkestone to retain works from each triennial, depending on budgets and the artist’s intentions. The town’s streets are strewn with works from previous festivals, some of which have formed integral elements of the town (such as Payers Park, an intervention from 2014 by Muf Architecture/Art).

Sara Trillo, Urn Field. Folkestone Triennial, 2025. Photo: Veronica Simpson.

About 30 metres (100ft) away, rising to the clifftop, is Trillo’s Urn Field, sculptures responding to an iron age burial ground found on the edge of the town, where shards of pots and vessels were scattered among the human remains. Trillo has taken 10 of these fragments and turned them into large sculptural interventions that emerge from the dense and vigorous scrubland clinging along the cliffs. Vessels are decorated with elements or markings that draw on the original relics and the wild landscape around. Their pale, fossil-like forms turn the area into a sort of burial ground.

Hanna Tuulikki, Love (Warbler Remix). Folkestone Triennial, 2025. Photo: Lia Toby/PA Media Assignments.

From there, a wander up and along the edge of the cliff brings us to an old first world war shelter, where Hanna Tuulikki’s installation, Love (Warbler Remix), celebrates the marsh warbler – a bird that used to be found on the Kent coast, but, apparently, is no longer, “due to climate change”, says Tuulikki. This remarkable creature composes its song using samples of other birds it meets along the way – across Europe, the Balkans and down to South Africa. Tuulikki, who was putting the finishing touches to the installation when I arrived, said she was “inspired to think of migration as a force that is central to all life on Earth”. She spent time with a group of ornithologists listening to a seven-and-a-half-minute recording of a marsh warbler. By analysing it in forensic detail, they were able to identify 68 different songs and species. For the installation, displayed across the back of this open shelter, she reimagines this song as that of a fictional bird she calls the “love warbler”, with colourful charts demonstrating the bird’s geographical range and breaking down each individual “tribute” in that recording to show what has inspired it, as well as how each fragment looks on a sonogram. On headphones, you can listen to a song she has composed, working with that seven-and-a half-minute recording, but slowed down to a “human scale” so we can identify the patterns and melodies, which turns it into a 21-minute recording. She has mixed the fragments of birdsong with snatches of love songs from various countries along that migratory route, along with live field recordings she is gathering from the sound mirrors at Dungeness. (These are concrete dishes built in 1928-30 to capture the sound of approaching enemy aircraft but completed just as radar came into use, and therefore never deployed. The site has now become an RSPB-protected bird sanctuary.) It is a wonderful idea, which turns into something rather complicated in its execution – the charts are so detailed and the sound work so layered, as well as fragmented, that possibly only the most sonically gifted, or ornithologically inclined, will have the patience to decipher them.

Dineo Seshee Raisibe Bopape, Ka Pheko ye (curse dissolved). Folkestone Triennial, 2025. Photo: Veronica Simpson.

Down from the cliff, on another open grassy stretch, is Dineo Seshee Raisibe Bopape’s work. More visually compelling and thoughtfully composed than the snaking earth wall with which she filled the Serpentine North gallery in Back to Earth (2022), this one is like a large gravestone, or an ancient road marker: a big fat, pale and creamy earthwork, it is contoured into a lozenge shape, flattened around its edges and across its front and back so you can clearly see all the layers of matter that have been compressed into it, many of which have been mined or harvested from the surrounding countryside, including coal and straw. On its top is a little grass-woven “spirit house”, which the artist hopes might be a home for birds. On the back there’s a “gene map”, which Bopape proposes as an aid to releasing ancestral trauma. The work is called Ka Pheko ye (curse dissolved): The Long Story, suggesting it holds a blessing for dissolving inherited burdens.

Rae-Yen Song 宋瑞渊, song dynasty. Folkestone Triennial, 2025. Photo: Veronica Simpson.

A couple of hundred yards away, back in the tight weave of Folkestone’s residential streets, we find the handsome, redbrick St Peter’s Church, which has been known for centuries as the “fishermen’s church” (Peter being the patron saint of fishermen). Here, over the central aisle, the Glasgow based artist Rae-Yen Song has placed a colourful, elongated costume, in which she examines the shared ancestry of life on land and sea. Song Dynasty (2025) is inspired by the sand mason, a worm found around the UK’s southern coast that crafts its home from sand and shells to form a protective tube from which an ornate branching structure protrudes, which it uses to catch food. The colours Song has used are rich and celebratory, the structure reminiscent of the sand mason, as well as traditional Chinese dragon and lion dance costumes. Delicate embroidered sea creatures are visible in its undersides. And it is designed to be worn, with five head-holes emerging along its five-metre length.

Staying with watery subjects, down at the harbourfront is Cooking Sections’ Ministry of Sewers. The duo, Daniel Fernández Pascual and Alon Schwabe, were nominated for the Turner Prize in 2021 and are more typically associated with food-related interrogations. This Folkestone work was inspired by the huge controversies over the last few years around Britain’s national and local water management – or mismanagement – using as a provocation the proposal in feminist writer Sara Ahmed’s 2021 book Complaint, that “to complain is to open a door … the more a door is opened, the more the door is open. The more a path is used, the more the path is used.”

Cooking Sections, Ministry of Sewers. Folkestone Triennial, 2025. Photo: Veronica Simpson.

The duo has taken occupancy of Folkestone Harbour’s old Customs House and dressed it up as the Ministry of Sewers. They have engaged assorted “ministers” (activists from the area), wearing T-shirts with distinctive logos, who, over the 100 days of the triennial, will take turns to sit at the Minister’s Desk, at the far end, and listen to the many complaints and issues local have around sewage spills, sick seals, banned beach days and worrying rashes. The inner walls of the Ministry are plastered with protest banners, useful data, photos and newspaper articles. A double row of chairs at its centre is ready for protesting citizens to wait their turn – you can book a session on charts on the wall. Working closely with a group of lawyers, these gathered testimonies will be compiled to see if there are legal cases to be made, and any hope of holding water companies to account. As the duo declares on the day: “A lot of our work is to empower cultural institutions to engage with civic issues.” This is a brilliant way of harnessing local voices to advocate for positive change and seas that are safe to swim in.

J Maizlish Mole, Folkestone in Ruins. Folkestone Triennial, 2025. Photo: Lia Toby/PA Media Assignments.

A different kind of sifting, above and below ground, is J Maizlish Mole’s preoccupation, examining 1,200 years of old books and maps, from 725 AD and ending a century ago in 1925. Mole then spent five weeks walking 215 miles around town to identify where these mostly vanished elements were once situated. Called Folkestone in Ruins, the resulting maps, enamelled for posterity, are posted all around the town. People can pore over and savour the folklorish labels and references. For example, the Terrible Cliff, that regularly reveals new quantities of human bones whenever there are excavations. Dotted lines reveal a landbridge that is supposed to have existed between the UK and France. Current landmarks are situated in this pre-1925 landscape – including the Great Burstin hotel, which is shaped like a giant ferry and currently sits on the harbour’s edge but in this map is floating at sea. Maze’s practice has been described as a form of “upside down archaeology”.

Rubiane Maia, In Search of Darkness. Folkestone Triennial, 2025. Photo: Veronica Simpson.

Rubiane Maia’s In Search of Darkness is a film and performance work, set within a small, shed-like recess along the harbourfront. Blackened out the better to see the circular projection that is broadcast on to an earthy, circular pile, the room is animated by chants, songs and prose that speaks of our need to honour the Earth and treat darkness “not as something to fear but as a space of feeling and growth”, as the caption in the Folkestone Triennial flyer so accurately states. Maia’s work is inspired by the ancient bones found in and around Folkestone – this place that has been inhabited for thousands of years – and one of the more memorable lines on the compelling soundscape of her film was: “By caring for bones we care for memory.”

Dorothy Cross’s Red Erratic is a work that hits heavy, in every sense. Into this huge chunk of Damascus Rose marble, originating in Syria but which the artist discovered among the luminescent white rocks of a Carrara marble storeroom, Cross has carved shuffling, truncated feet. The rock sits on the waterline, down some steps along the Harbour Arm – on a level with Antony Gormley’s trademark standing man, from an earlier triennial. Every time the tide rises, the waterline comes perilously close to these feet. It was installed by crane in June 2025 – and there is hope that this, too, may remain. The Erratic of its title refers to the geological term for a rock that has been transported, often across continents, by glaciers, and dropped only when the ice has melted. Cross says she felt an almost visceral sense of shock when she encountered this chunk, and the work as she has rendered and placed it, resonates with contemporary cultural, social and economic shocks of its own.

Emeka Ogboh, Ode to the Channel. Folkestone Triennial, 2025. Photo: Veronica Simpson.

Down along the easternmost edge of the harbour is the sonic element of Emeka Ogboh’s multisensory, multipart work Ode to the Channel. This main component is a soundscape shared via speakers placed in the roof of a walkway that leads down to the beach at low tide, but is flooded at high tide. Ogboh worked with a specially formed group of local singers, whom he has dubbed The Sirens, singing modern sea shanties co-composed with a local musician, Rachel Gerrard, starting with that signal moment when a megaflood destroyed the land bridge connecting England to Europe. Ogboh has also developed an ice-cream, Coastal Drift, with local makers Herbert’s, and a beer, Doggaland, with local brewery Docker.

Monster Chetwynd, Salamander Playground. Folkestone Triennial, 2025. Photo: Lia Toby/PA Media Assignments.

With such a high hit rate of artworks that deal so powerfully and conversationally with the town, with each other, and with the issues of the day, there are bound to be a few that don’t quite gel. Monster Chetwynd’s Salamander – a big, colourful, fibreglass yellow creature at the top of Payers Park is one of them. It is only a temporary Salamander, flagging up the news that there will soon be a Salamander-themed playground in a new public space to be carved out of the existing bus garage. The artist apparently loves salamanders because they are under-celebrated animals and because they can regrow their limbs and even their organs.

John Gerrard, Ghost Feed. Folkestone Triennial, 2025. Photo: Veronica Simpson.

John Gerrard has placed a dramatic film work outdoors (not always a good idea, due to low visibility), on a raised terrace used by some of Folkestone’s most fashionable bars and restaurants. Ghost Feed shows a white-cheeked spider monkey staring at a smartphone, while a virtual forest landscape is revealed around it, from smouldering forest fires to war-ravaged battlefield. Apparently made within Unreal Engine, a 3D computer graphics game engine, there are elements of real-time animation that moves the scene from day to night, but the technicalities of how this works – and why it matters – eluded me.

Laure Prouvost, Above Front Tears, Oui Connect. Folkestone Triennial, 2025. Photo: Veronica Simpson.

I was also a little underwhelmed by Laure Prouvost’s Above Front Tears, Oui Connect. A sculpture of a hybrid, three-headed bird sits on top of a remnant from Folkestone’s ferry-terminal infrastructure. For some reason it has large breasts, prominent nipples, and a plug dangling from its rear end. There is also a fledgling, presumably related, but with only one head, perched perilously across a small stretch of water, unattainable. The work is accurately described as being “poised between the sea and the sky”, and “symbolic of thresholds”. But when other works articulate their resonance and relevance so clearly, its subtleties don’t do it any favours.

Céline Condorelli’s Dedication (To the Sea, To the Sea) is also a mite underwhelming. A number of flagpoles have been put up around Folkestone, bearing squiggly, indecipherable graphic flags with incomprehensible symbols that pivot at whim. They are said to be flagging up the various futures that have been imagined for Folkestone, but they seem flimsy and insignificant compared with most of the work around them.

A last artwork – by Prabhakar Pachpute – had not arrived, having been held up en route, so I can’t include it in this review. Overall, though, this is a richly rewarding triennial, worth lingering over – and returning to. Carey, referring to the title she has given this outing, says: “Embedded in the phrase is the understanding that the layers and contours of the land have not only influenced where we find ourselves now, but can also suggest which direction we should take next.” One hopes that the majority of works here provide sufficient nourishment and inspiration to divert us on to a more wholesome and resilient route than we, as a species, seem to be following.