.-Image-courtesy-Ikon-Photo-by-David-Rowan-(1).jpg)

Seulgi Lee, Slow Water, 2022. Installation view, Ikon Gallery, 2025. Image courtesy Ikon. Photo: David Rowan.

Ikon Gallery, Birmingham

25 June – 7 September 2025

by DAVID TRIGG

The large suspended wooden trellis in the opening room of this show at first appears plain and nondescript. It is only when you walk under the circular canopy, and begin viewing it from different angles, that its true variegated nature reveals itself. Shifting combinations of intense pink, green, yellow and purple slats that were at first hidden from view now transform the rigid structure into a vivid interactive experience. This is Slow Water (2022) by the South Korean artist Seulgi Lee in collaboration with the French carpenter Pascale Theodoly. It brings the modernist grid into dialogue with munsal, the traditional latticework found in Korean homes – a meeting of old and new and east and west that characterises many of Lee’s works in this, her first UK solo exhibition at Birmingham’s Ikon Gallery.

Based in Paris since 1992, Lee has developed an intriguing collaborative practice that sees her working alongside craftspeople from around the world, incorporating their traditional techniques into elegant and captivating works that reference the histories of minimalism and conceptualism while examining the lines between art and craft, the past and the present, and the rational and the irrational. The title of this exhibition, Span, refers to an ancient unit of measurement derived from the distance between the thumb and little finger of the human hand. It speaks of an intimate, bodily way of measuring and encountering the world around us, including our relationships with the crafted objects on display and one another.

.-Image-courtesy-Ikon-Photo-by-David-Rowan-.jpg)

Seulgi Lee, Span, installation view, Ikon Gallery, 2025. Image courtesy Ikon. Photo: David Rowan.

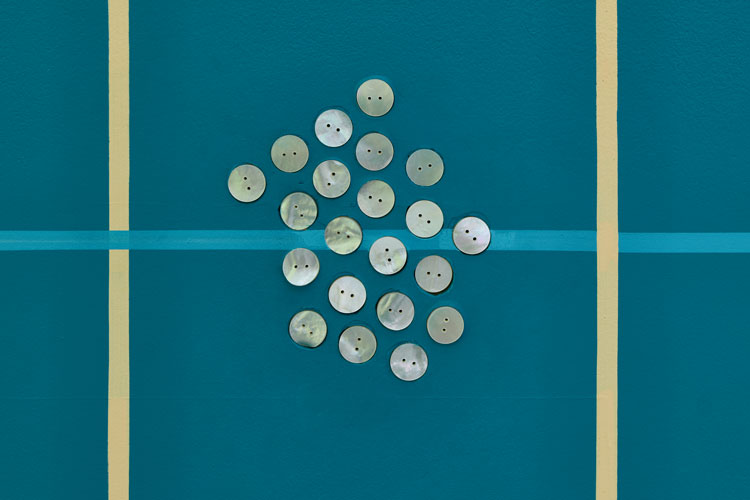

The grid is a recurring motif throughout the show, seen again in Moon Door North East (2023), a freestanding munsal form that refers to the changing shape of the moon during the lunar cycle. Flying Buttons (2025) is a series of colourful hand-painted wall and ceiling murals made in collaboration with Suyeon Kim, Jaewoo Park and Jin Mo Kim – Korean dancheong artisans whose work is normally seen adorning the wooden architecture of Confucian and Buddhist temples. At Ikon, their traditional designs are forsaken for rigid geometry responding to the specifics of the gallery’s Victorian schoolhouse architecture. Highlighting Lee’s penchant for the fantastical, the work’s title suggests that these multicoloured grids are perhaps maps, charting the course of imaginary airborne buttons as they flutter like butterflies from room to room.

Seulgi Lee, Span, installation view, Ikon Gallery, 2025. Image courtesy Ikon. Photo: David Rowan.

One mural has several real mother-of-pearl buttons physically embedded into it. Hand-crafted by local maker George Hook, whose family has been associated with the mother-of-pearl trade since 1824, their iridescent surfaces shimmer against a sea-green wall. Typically made from oyster and mollusc shells imported to Britain from Asia and Australia, these fasteners were once an affordable form of everyday jewellery, yet the work’s title, Six Pence (2025), again reveals Lee’s surreal form of associative thinking, linking these objects to the British tradition of finding a sixpence in a Christmas pudding – a sign of good luck. It also brings to mind the history of shells as currency; the cowry shell, for instance, was used as a means of payment in Asia as far back as the 13th century BC.

.-Image-courtesy-Ikon-Photo-by-David-Rowan-(7).jpg)

Seulgi Lee, Span, installation view, Ikon Gallery, 2025. Image courtesy Ikon. Photo: David Rowan.

Lee’s best known and longest running collaboration is with master nubi quilters from Tongyeong in South Korea, who have worked on the artist’s Blanket Project U since 2014. Nubi is a traditional form of padded quilt, which is sewn line by line in a process requiring years of training and intense concentration. In Lee’s silk blankets, which are mounted on differently coloured walls throughout the exhibition, traditional patterns are replaced by striking geometric abstractions that represent Korean proverbs or vernacular expressions.

The key to deciphering these works lies in their titles, which provide the English translation and meaning. For instance, in U: Drink the kimchi soup = To hope for something to be given (2024), a large red disc positioned amid various hard-edged shapes in blue, pink, green and brown could feasibly be read as a soup bowl seen from above. Similarly, in U: My three-foot nose = I’m too ground down to help anyone else (2018), an elongated mauve triangle suggests a nose. British idioms are also represented; in U: A piece of cake = Easy (2025) the triangular and semicircular forms playfully evoke a slice of delicious dessert.

As with many of Lee’s works, her blankets are visually generous and impeccably crafted. In a world where traditional nubi textiles have been largely replaced by mass production and where vernacular idioms are giving way to internet memes, there is a sense in which the artist’s project is an attempt at preservation, if not an act of resistance. The same could be said of her Basket Project W (2017), which similarly explores the relationship between image, craft and language through a collaboration with female basket weavers from the village of Santa María Ixcatlán in Oaxaca, southern Mexico.

.-Image-courtesy-Ikon-Photo-by-David-Rowan-(2).jpg)

Seulgi Lee, Span, installation view, Ikon Gallery, 2025. Image courtesy Ikon. Photo: David Rowan.

.-Image-courtesy-Ikon-Photo-by-David-Rowan-(3).jpg)

Seulgi Lee, Span, installation view, Ikon Gallery, 2025. Image courtesy Ikon. Photo: David Rowan.

Distributed at various points around the exhibition, these conjoined baskets of varying shapes and sizes perch atop thin brass armatures (made by the French craftsman François Lunardi). Their titles reflect the artist’s fascination with the Ixcatec language, which reportedly is now spoken only by a handful of elders in the mountain village visited by Lee. For instance, W / Sa la si tundu tzude chitjiu juwa, alias, The madman has a broken blue (green) nose (2017), derives from a curious saying that Lee heard from the weavers and which is reflected in the sculpture by a strange, proboscis-like protrusion. However, it is not always apparent how the baskets relate to their titles; W / Usatcha, alias, Coyote (2017), for instance, bears no clear resemblance to a canine or, indeed, any other animal.

Several works in this show are easy to miss, such as Han (2024), a small glass sphere blown by the Seoul-based glassblower Jongin Kim in which water from the titular river has somehow been sealed. Elsewhere is Espan (2024), a silk ball embroidered by Japanese temari artisans and which Lee has hidden high up on a ceiling beam, its concentric blue rings appearing to narrow and expand when viewed from different positions.

.-Image-courtesy-Ikon-Photo-by-David-Rowan-(5).jpg)

Seulgi Lee, Span, installation view, Ikon Gallery, 2025. Image courtesy Ikon. Photo: David Rowan.

With most of Lee’s works being made by workers outside the art market, the thorny question of exploitation is one of which the artist is acutely aware. Her discussions with her artisan collaborators, such as nubi quilter Sungyoun Cho, see that they are paid fairly for their labour. And, unlike many other artists who outsource fabrication, she also ensures that each maker is properly credited in her exhibitions. For Lee, the traditional skills of others are not simply a means to an end, rather, her art is a way of honouring them.

While Span celebrates the enduring dexterity of the human hand, its crafted objects also serve as vehicles for Lee’s flights of fancy. Her mother-of-pearl buttons are, she says, “stars walking on clothes”; her suspended wooden trellis imagines viewers underwater looking up at “the reminiscence of colours reflected”; and she wonders if her nubi blankets might influence the dreams of those who use them. Lee’s playfully idiosyncratic works are as much a feast for the imagination as they are for the eyes.

.-Image-courtesy-Ikon-Photo-by-David-Rowan-(4).jpg)

Seulgi Lee, Span, installation view, Ikon Gallery, 2025. Image courtesy Ikon. Photo: David Rowan.