Jumana Emil Abboud and Anawana Haloba speaking to Studio International at the opening of Artes Mundi 11, National Museum Cardiff, 2025.

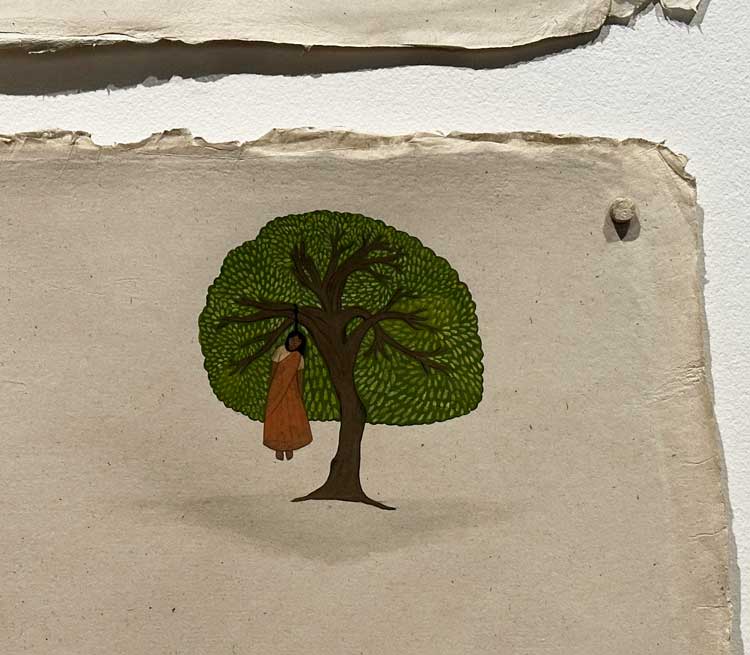

You don’t notice the tragedies at first, among the tiny figures in Sancintya Mohini Simpson’s exquisitely painted multipanel works on paper, at the National Museum Cardiff. Cleverly subverting the usual tropes of Indian miniature painting – which Simpson (b1991, Meanjin/Brisbane) learned during an intensive, month-long apprenticeship in India with the master painter Ajay Sharma in 2013 – instead of the typical subjects of palaces, gardens and princes, Simpson presents us with factories, bleak and dusty forecourts and barracks-like accommodation blocks. They are artfully arranged with stretches of greenery, a few trees, undulating strips of river and sea; on the lower left side is a field of flaming sugar cane. But in among the scattered, white-robed workers walking, sitting, carrying and raking, there are horrors you only see up close: a woman hangs by a rope from a bough of one of the trees; a man lies in a pool of blood, a ruby-red splotch against the overwhelming palette of grey, ochre, brown and green.

Sancintya Mohini Simpson, installation view, National Museum Cardiff, Artes Mundi 11, 2025-26. Photo: Robin Maggs.

Sancintya Mohini Simpson, installation view (detail), National Museum Cardiff, Artes Mundi 11, 2025-26. Photo: Martin kennedy.

The subtlety and restraint of these moments of trauma add so much weight to Simpson’s narrative. As does her personal background: she is the descendant of indentured labourers, who were whisked away from their Indian homes in the late 1800s and early 1900s by British colonial occupiers, to work on South African sugar cane plantations in Natal. Simpson’s work across the two Artes Mundi venues in Cardiff – the National Museum and Chapter Arts – speaks of an intense process of researching, thinking through and clarifying her themes and materials over the last two decades. It is for this reason, among others, that we should celebrate the existence of the Artes Mundi prize, now in its 11th iteration.

The biannual competition – with the largest cash prize, at £40,000, of any UK exhibition – was launched in Wales in 2002 with a mission to expand awareness of an international artist community whose work speaks to the most pressing issues of our time. The prize is so generous, in part, because most of the artists who are nominated have invested a great deal of time and energy on vital issues, exploring complex social and environmental crises, with little financial support or incentive – even if past winners, such as Theaster Gates (2014), John Akomfrah (2016) and nominee Otobong Nkanga (2018), have now reached that enviable and rarefied strata of artists who are well rewarded for their talents.

Sawangwongse Yawnghwe, installation view, National Museum Cardiff, Artes Mundi 11, 2025-26. Photo: Robin Maggs.

Where once the work was shown entirely in Cardiff, for the 10th iteration in 2023, the exhibition was shared across different Welsh venues, creating a richer, solo presentation for each artist in each region, drawing art lovers deeper into the Welsh art ecosystem, and providing a “taster” across the spectrum in Cardiff. This year the Artes Mundi team has continued that evolution, with all artists exhibited in one long, hallway presentation at the National Museum Cardiff, with additional solo presentations. Simpson’s solo show is at Chapter Arts, as stated. At Aberystwyth Arts Centre, Anawana Haloba is paired with Sawangwongse Yawnghwe. At Glynn Vivian Art Gallery Swansea, Kameelah Janan Rasheed takes up the grand Victorian museum’s central hall. At Mostyn in Llandudno, the Peruvian artist Antonio Paucar is paired with the Canadian Palestinian artist Jumana Emil Abboud.

.jpg)

Kameelah Janan Rasheed, installation view, National Museum Cardiff, Artes Mundi 11, 2025-26. Photo: Robin Maggs.

At Swansea, in a presentation of powerful print and film work, Rasheed (b1985, East Palo Alto, California; lives and works Brooklyn, New York) plays dexterously with the space, and with your brain, through her clever, ingeniously crafted verbal and graphic gymnastics. Three huge banners of white print on black, draped from on high, display an alphabetical listing of unlikely but poetic pairings: charismatic complexion; delicate drone; egotistical error, and so on. Elsewhere, she displays posters – very much evoking early work by Jenny Holzer – ridiculing trite catchphrases, but hers are served with a trenchant twist that bears witness to the US’s deeply divisive racial and class politics. “Purchase the proper boots with which to pull yourself up by the bootstraps” is one example. “Take it like a man but don’t take it up with the man” another.

In Aberystwyth, Yawnghwe (b1971, Shan State of Burma; lives and works in Zutphen, Netherlands) explores his own regional and family history in Burma, now Myanmar. He was born into the Yawnghwe royal family of Shan. His grandfather was the first president of the Union of Burma (1948-62), established after independence from Britain. His grandfather, however, died in prison after the 1962 military coup, driving the family into exile in Thailand and then Canada, where Yawnghwe grew up. In Aberystwyth and also Cardiff, Yawnghwe presents a new series of paintings of historical family photographs in key places and at key moments in their story, framed by vivid textile borders evoking the continuing fragmentation of families and nations.

There is also a recent strand of work depicting flower arrangements – innocent-seeming still lives in thick impasto, but always featuring opium poppies, the crop whose potent harvest has led to so much greed and devastation across the globe, but the trading of which funded Burmese resistance fighters.

.jpg)

Antonio Paucar, installation view, Mostyn, Artes Mundi 11, 2025-26. Photo: Rob Battersby.

At Mostyn in Llandudno, Paucar (b1973, Huancayo, Peru; lives and works in Berlin and Huancayo) displays filmed performance, sculptures and video works, foregrounding rituals and interventions in the wildest of Peruvian landscapes. Like an Andean Andy Goldsworthy, his videos feature the artist walking or interacting with the land or nature in ways that demonstrate the intense connection he feels with his native geography – the fact that he almost always performs these acts barefoot and stripped to the waist amplifies a visual and emotional link between his lean, sinewy frame and the gnarled, mostly arid terrain. In one striking film he appears dangling upside down from a tree, bound by his feet and wrapped in a white “cocoon” of bandages (Suspendido en la Queñua (2014). The camera follows his struggles, wriggling and twisting, until he eventually frees himself from the white wrappings, to end up perched, like a cougar, along a branch. Here and at the National Museum Cardiff, there are also sculptures made from black and white alpaca wool, demonstrating traditional knotting, with the long resulting ropes formed into sculptural geometries. It’s not clear what these works are trying to say, though apparently they resonate strongly with Welsh textile traditions.

Jumana Emil Abboud - interview: ‘We can be anything we want to be through the stories we can make and unmake’

For her solo presentation at Mostyn, Abboud (b1971, Shefa’Amr; lives and works in London and Jerusalem) combines new and previous work developed along themes familiar to those who saw her show The Unbearable Halfness of Being at Documenta 15 (2022). Her work explores landscapes as sites of memory and imagination. Drawing on folklore, mythmaking and storytelling, she articulates the strains placed on community and family life through repeated displacement and her own Palestinian experiences of annexation. For Artes Mundi, her key theme is water: the role of natural springs, wells and rivers in local myth and lore, which she explores through the practice of divining – not so much water divining in the traditional sense, as story divining. This divining includes working with local communities to create shared stories around water sources that are then retold as they process through the landscape, often captured on film. She established this practice first in Palestine, has since taken it to Japan and Germany, and now brings it to Wales. For the week preceding Artes Mundi’s opening at Mostyn, she accompanied locals on their own journeys visiting significant wells and freshwater springs around Llandudno. Some of the resulting stories were shared in a performance at the gallery on the show’s opening night.

“My relationship with water goes back a very long time,” she tells us. “It goes back to my childhood and stories told by my female elders around or under olive groves.” While those tales were usually cautionary, intended to keep children away from water sources, she reframes that relationship, embracing their importance as places of gathering. “Stories and folklore and water: it’s all interconnected,” she says.

.jpg)

Jumana Emil Abboud, installation view, Mostyn, Artes Mundi 11, 2025-26. Photo: Rob Battersby.

At Mostyn and in Cardiff, Abboud presents drawings as part of her “imaginative recreation” of ancient and modern mythologies, using natural ink and materials. “My practice finds its resting place in a naive approach. Where is the innocent approach to the landscape and the human story? So much of our experience is already burdened with … political thoughts of diaspora, occupation. We are burdened and carrying these stories with us. It makes our imagination so limiting. I want to go back to this place of innocence.”

Scattered around the room are totems or charms inspired by precious or significant items that she has asked people to bring her from water sources of significance. They have been cast, remodelled in wax, and placed around the gallery, on tables and shelves, accompanied by handwritten notes, lyrical phrases and poems. The paler ones are made from candle wax (in Palestine, it has long been traditional to burn candles near significant water sources), others from beeswax, occasionally mixed with turmeric to give them a warm, golden hue. In Mostyn, she is also showing a series of embroideries made in conjunction with a Welsh community group, working with female refugees. There are also three glowing, hand-blown glass bowls, made with artisans in Marseille. The bowls are intended to operate as notional portals to other realms, echoing the belief systems of Welsh druids, who revered water sources as places for divination and communion with the spirits.

Anawana Haloba – interview: ‘With everything that’s going on in the world, we talk about things, but we really don’t listen’

At Aberystwyth Arts Centre, Haloba (b 1978, Livingstone, Zambia; lives and works between Livingstone and Oslo, Norway) has staged an “experimental opera”, as she terms this continuing strand of research: using the format of a classical, European cultural phenomenon to interrogate its relationship with older, folkloric versions from her Zambian homeland, and questioning that European assumption of superiority over these more ancient forms. Called How to (Re) Pair My Grandmother’s Basket; An Experimental Opera (initially 2021, this version 2025), she places assorted objects – simple, everyday items, primarily horns, but also baskets and calabash – around a low stage. Spoken monologues and songs emerge from speakers placed inside each object in a choreographed incantation, from a libretto devised by Haloba. The work is described as “a dialogue among non-gendered characters who traverse geographies, cultures and societies, that speaks to our times”. Drawing on memories embedded in oral traditions, the statements and declamations have an arresting, universal quality. Her father’s recorded voice is present, in a celebration of timeless oral traditions, songs and ceremonies. She says here: “Life in itself is an operatic happening: because it has love, it has tragedy, it has different things happening at each point in one’s life.”

In her interview, she references the Nigerian poet, playwright and 1986 Nobel Laureate Wole Soyinka, who said he was attuned to opera through experiencing the drama and exuberance of Nigerian marketplaces. From her own Zambian childhood experience, she says: “The operas we have are performed when there is a funeral, or a memorial. But because they talk about history, they become forms of knowledge dissemination. They sing about things that happened thousands of years ago. They are a way of archiving knowledge. And make human beings perform as archives themselves.”

For her presentation at Cardiff’s National Museum, she brought a version of an earlier work, Listening Stations, this time with four terracotta clay vessels, placed on stands at head height, enticing the listener to lean in and hear the “insights of scribbled poetry … reflecting what is going on in the world now … The viewer is supposed to put their face in the bowl for them to hear. To have a conversation in their mind.”

.jpg)

Sancintya Mohini Simpson, installation view, Chapter, Artes Mundi 11, 2025-26. Photo: Polly Thomas.

Sancintya Mohini Simpson

Simpson’s work for Artes Mundi feels vital – and new, given that this is her first presentation in the UK. With her degrees in photography and creative writing, she has arrived at her subject – the impact of forced labour on people, landscape and identity, and the way those traumas are passed down through generations – through a deep investigation of her own personal inheritance (as mentioned earlier). This body of work has been more than a decade in the making, starting with painstaking investigative work to find out from where in India her ancestors were removed (these indentured labourers were identified only by number, and then only the males), then accompanying her mother on a trip to that place of origin, in 2012, which Simpson documented photographically. She then learned the art of miniature painting in 2013, which she deployed by painting on to the same photographs. Having fully arrived at her methodologies and themes, these now wholly painted narratives fully inhabit the space.

.jpg)

Sancintya Mohini Simpson, installation view, Chapter, Artes Mundi 11, 2025-26. Photo: Polly Thomas.

The Chapter Arts installation reinstates the Cardiff National Museum work’s narratives through two more “miniature”-style paintings – this time unfurling as scrolls, as mythical or biblical stories would have been rendered, for ease of transport and transmission – but also a powerful new version of her installation, Vessel (2025). Comprising dozens of her hand-made lotas (traditional, round-bellied pots used for food or water) formed from black clay and fired in sugarcane mulch and sawdust, they lie tossed around a rich, reddish landscape of earth – earth that we learn has been taken from Cardiff’s graveyards; a tonne of earth is apparently excavated for every grave dug. There is also a powerful 2021 video, Dhuwã (a term used by indentured people of Natal for “smoke”), with a haunting soundtrack by Simpson’s brother, Isha Ram Das, with whom she often collaborates. The collaged two-screen video offers viscerally affecting imagery of the sugar cane fields of North Queensland, first rustling in the breeze and then bursting into flames; its emotional and sensory impact turbo-charged by the scent of burning sugar cane, which is released into the gallery. The final flourish in this potent cocktail comes from a poem, which accompanies the watercolour scrolls, Kappal Kari/Kũli Kari (2025). Scrawled by hand over the wall, it evokes the journeys of her ancestors, the forced shipment, a brutal life in captivity. But there’s also the potential for transformation in the concluding lines: “We unmap ourselves / against the earth / learning to unfurl / we echo multitudes / and waves of neural synchronicity.”

Simpson, who lives and works on Yuggera, Jagera and Turrbal Country, has had solo exhibitions at: Jameel Arts Centre in Dubai; Bundanon Art Museum, New South Wales; Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts; Milani Gallery, Brisbane; Firstdraft Sydney; and Hobiennale Hobart. Recent group exhibitions include: Shajah Biennial 16; the 11th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art, Queensland, and Savvy Contemporary, Berlin.

Having been to the four most recent Artes Mundi exhibitions, it is clear that the narratives of the mainstream art world have shifted – the voices of indigenous communities, artists from the global south, the issues of climate emergency and species extinction have moved into the mainstream in contemporary art in a way that would have been unforeseeable in 2002. This is, in many ways, the sanest response to the escalating crises around us. But it means that, for every crisis now foregrounded at the Artes Mundi biennials, we may have seen other artists (including previous nominees) showcase their talents and these issues elsewhere, and sometimes more powerfully. Nigel Prince, who took over as director at the last iteration, says: “Yes, you could say that there has been some overlap, say with the last two Turner prizes. But those are mostly artists based in the UK. I like to think we retain a certain distinctive flavour, our artists are international, and most have not had major museum shows here. They deserve wider acclaim. Their work sets in motion discussions between the local and the global. And we have a mission beyond the prizes: ‘Learning about ourselves by learning about others.’ That is absolutely appropriate at this time.”

For me, there were three especially strong presentations. Rasheed’s Swansea show felt profound: visually powerful, playful and skilful, leaving an enduring impression of the fraught political context in which it is made. Abboud’s stood out for the deftness with which she articulates real and pressing crises, but lifts us above the traumas of today’s newsreels, connecting us with more ancient relationships and narratives. All her work speaks of care: of summoning the feeling for nature and landscape that we have as children, seeing it as a place of magic and transformation. Simpson’s work was especially powerful for the cumulative impact and synergies between the works in clay, on paper, on film, sound and smell. She articulates the acknowledgement of trauma, and the possibility that, through care and attention, a kind of healing is possible.

Artes Mundi 11, 2025

National Museum Cardiff and venues across Wales

24 October 2025 – 1 March 2026

Interviews by VERONICA SIMPSON

Filmed and edited by MARTIN KENNEDY