Encounters: Giacometti x Huma Bhabha, installation view, Barbican Art Gallery, 8 May - 10 August 2025. © Max Creasy / Barbican Art Gallery.

Barbican, London

8 May – 10 August 2025

by TOM DENMAN

The urge to anchor the unruly present in the seemingly – if illusionistically – solid past is irresistible, it would seem. For example, a huge exhibition focusing on the influence of the sculptor Medardo Rosso on an abundance of modern and contemporary artists has been touring through Mumok in Vienna and Kunstmuseum Basel since the end of last year. Perhaps there is something about sculpture, too – its weight, its material resilience – that is reassuring in an era defined by indeterminacy. Now, a comparable, more focused approach is taken in an exhibition at the Barbican, London, revolving around another giant of European sculpture: Alberto Giacometti. Aligning the Swiss artist with Huma Bhabha, the current show is one of a slate of three, with the next two showing Giacometti alongside Mona Hatoum and Lynda Benglis. Focusing on female artists from different parts of the globe, with two originating from non-western countries (Bhabha is from Pakistan, and Hatoum is a Lebanon-born Palestinian), the trilogy seems to be aimed at opening up the canon, exposing its amorphousness and porosity. Thus, perhaps as a reflection of the times, it might be said that the show does two things at once, proving Giacometti to be both a bedrock and constantly in flux.

Encounters: Giacometti x Huma Bhabha, installation view, Barbican Art Gallery, 8 May - 10 August 2025. © Max Creasy / Barbican Art Gallery.

With the Barbican’s usual gallery closed for refurbishment, the show is being held in an L-shaped room – normally used as a restaurant – overlooking the central piazza, the makeshift gallery affording the works a sense of contingency, as if they were somehow “backstage” and not meant to be seen. The effect of this is to strip Giacometti of some of his institutional, art historical and market-backed monumentality, the experience of which is one of the incidental rewards of visiting this show. The critic Francis Ponge wrote of Giacometti’s straining, elongated figures in 1977: “The man on his pavement as on a burning plate of steel; who cannot detach his gross feet from it.” Displayed as they are, Giacometti’s wandering souls project some of this sentiment on to the people strolling, eating, chatting and loafing down below, as if the sculptures were demonically dogging their movements – reminding us of the tension between transience and situatedness that characterises much of what it is to be human, while also pitting against each other the utopian and dystopian sentiments evoked by the Barbican’s brutalist architecture.

Alberto Giacometti. Walking Woman I, 1932. Bronze, 150.3 x 27.7 x 38.4 cm. Fondation Giacometti.

Returning to the pairing of artists, however, a query that immediately comes to my mind when seeing this show concerns the selection of Giacomettis. It concentrates almost entirely on work from after 1935, the year of his abrupt move away from his preoccupation with the surrealist possibilities of African, pre-Columbian and Cycladic art – a move that occasioned his expulsion from the surrealist group. Only one work dates from before this moment, Walking Woman I (1932), although you would be forgiven for thinking it dated later, since it is superficially close in form to the tall, spindly figures he made subsequently – which are what this show otherwise focuses on. The smoothness of contour of Walking Woman I, however, is more akin to the surfaces of his earlier work, and the dish-like cavity in the woman’s chest recalls the concave abdomen of his 1927 Spoon Woman (not included in this show), a work inspired by the ceremonial spoons of the West African Dan people.

Huma Bhabha. Member, 2024. Painted and patinated bronze, 96 x 38 1/2 x 24 1/2 in (243.8 x 97.8 x 62.2 cm). Photo: Kerry McFate. Courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner Gallery.

The focus on Giacometti’s post-surrealist period may strike as surprising, since Bhabha’s practice seems to pertain to western modernism’s now notorious (for being colonial) appropriation of non-western artforms that was fundamental to so many surrealist images. Here we see a swathe of Bhabha’s work, mostly from the past three years or so. Four forbidding black cuboidal blocks stand in the corridor between Barbican’s library and gallery (all 2024), with simple grooves delineating limbs and claws and other body parts, some of them crudely painted. On top of each is an animal skull, which Bhabha appears to have stuck on without worrying about verisimilitude: in Mr Stone (2024), for instance, the skull is wedged into the neck nose down. Possibly robots, or ancient deities, they appear to be made of painted polystyrene, but Bhabha has made them by carving cork and casting it, along with the bone fragments, into bronze, which she then painted. Bhabha’s layered ambiguity shuns any hard-and-fast reading, and yet it speaks to Giacometti’s pre-1935 integration of prehistoric or non-verisimilar ceremonial forms.

Huma Bhabha. Lodger, 2024. Cast iron and concrete pedestal, 65 x 24 x 24 in (165.1 x 61 x 61 cm). Photo: Kerry McFate. Courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner Gallery.

One could argue that it could be reductive to place Bhabha alongside Giacometti’s earlier work, encouraging simplistic postcolonial interpretations and pinning the artist to a singular critical approach. Once in the gallery, we see scattered on low plinths Bhabha’s small works in terracotta representing what seem to be neanderthal body parts, as if freshly dug from the earth: dusty, semi-decayed heads and feet, what could be a pair of vertebrae. They could almost be props for an archaeological movie, yet there is slippage between the theatrical and the real (or perhaps it is simply a case of the theatre “working”): their pre-historic feel, no matter how “artificial”, pinches an ancestral nerve. They are amidst three of Giacometti’s small clusterings of sticklike figures welded to heavy, rectangular bases from 1950. Bhabha’s work shares some of their spectral quality, the suggestion being that both practices are somehow archaeological, digging deep psychically. What is brought out by this alignment is the sense that the surrealist preoccupation with the unconscious continued in Giacometti’s ravaged distortions of the human figure. As an observation on Giacometti, this is unlikely to be new, but here one can experience it as a dialogue between past and present.

Alberto Giacometti. Man with a Windbreaker, 1953. Bronze, 50 x 28.6 x 22.5 cm. Fondation Giacometti.

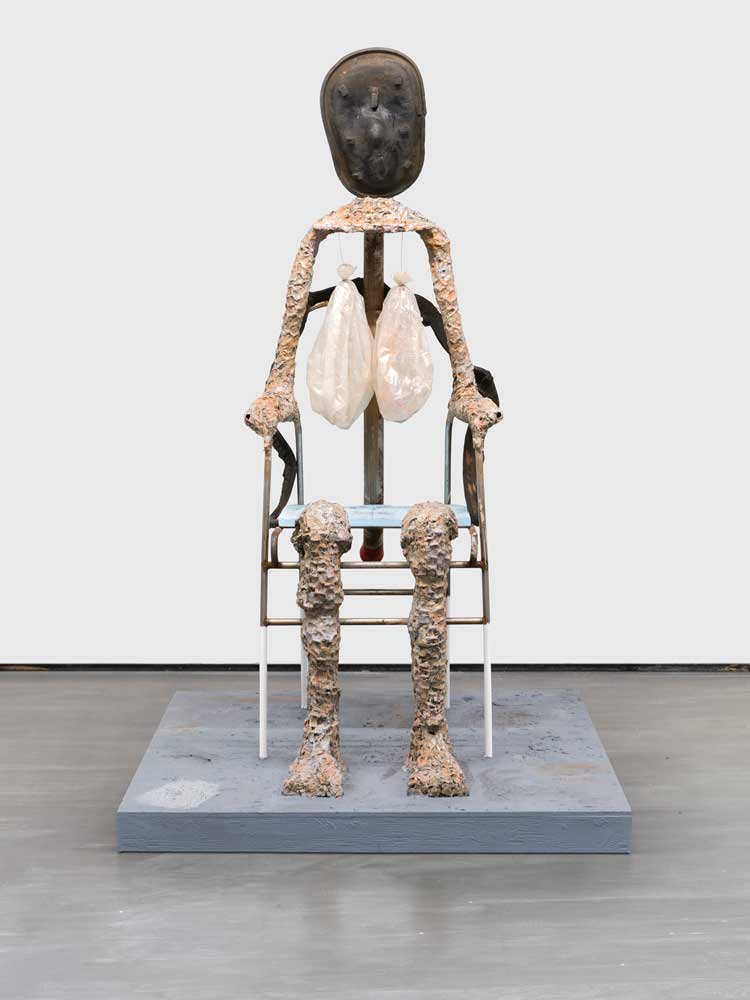

Yet anyone informed of Giacometti’s practice cannot help but think of other, closer comparisons with Bhabha’s work here, such that their absence becomes distracting. Giacometti’s Man with a Windbreaker (1953) – his gashed torso massive compared with his pinprick of a head, creating the almost cinematic effect of him rapidly and perplexedly emerging from the earth like a volcano – is placed beside Bhabha’s Lodger (2024), a rusty cast iron abstraction consisting of a cassette-like rectangle containing an animated scrunching of bent iron, turned vertically and placed on a curvilinear form suggestive of a neck and shoulders. The abstract interplay of unnaturalistic and yet potentially representational forms bears a closer kinship with Giacometti’s earlier experiments with similarly abstracting the human figure – possibly drawing on non-western or prehistoric models – in works such as The Couple (1926), which comprises two vertical, humanlike forms. Similarly, the incongruous materials and cage-like frame of Bhabha’s Mask of Dimitrios (2019) – a seated, hollowed-out, larger-than-human figure with two pendulous plastic bags seeming to act as breasts and a metal dish for a head – recalls Giacometti’s Invisible Object (1934).

Huma Bhabha. Mask of Dimitrios, 2019. Clay, wood, acrylic, oil, oil stick, plastic rubber, steel, wire, and Styrofoam, 78 1/8 x 48 x 60 in (198.4 x 121.9 x 152.4 cm). Photo: Daniel Perez. Courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner Gallery.

Maybe the inclusion of earlier examples of Giacometti’s work – along with the post-1935 figures – would have been a way of testing Bhabha’s playful ambiguity, the extent to which she does not necessarily exact a postcolonial critique but walks the fraught and blurred line between critique and homage. When an artist is positioned alongside a figure as influential as Giacometti, the contexts in which the latter operated cannot be totally ignored, especially if one’s work can be described as psychically charged. Genealogically ingrained in Giacometti’s surrealist experiments before his rejection of them in 1935 are the colonial histories that surround them, and a significant part of Bhabha’s relationship with this canonical artist hinges on this reality.