Kiki Smith at the studio. Photo: Courtesy Pace Gallery.

by ANNA McNAY

Kiki Smith (b1954, Nuremberg) weaves her works literally and metaphorically, intertwining folklore and anatomy, cosmology and technology. Reusing images over and over, collaging, cutting and drawing, she goes where she is led and creates works that speak to viewers on manifold levels.

Her latest exhibition, Woven Worlds, at Moderna Museet, Malmö, comprises more than 50 works from a career as many years in length, and, by juxtaposing tapestries with their cartoons and associated hand-coloured prints and drawings, it offers visitors an insight into the idiosyncratic thought processes and stages of development of the artist.

Smith spoke to Studio International by Zoom from her kitchen as she fed her cat and fought off intruding squirrels.

Anna McNay: Tell me about Woven Worlds. How involved were you with the selection of the more than 50 works included? How difficult a task was this?

Kiki Smith: It was easy. Originally, I was asked to show my tapestries, but I had already done that enough, and I wasn’t interested in doing it again. I said I would like to show how they mature: I would like to show the tapestries with their cartoons and to show how the same images keep moving around, having different lives, in different pieces. Sometimes, this is in a very literal way with the exact same images, and sometimes it is just as a category of images.

Kiki Smith: Woven Worlds, 2025. Installation view, Moderna Museet, Malmö. Photo: Helene Toresdotter / Moderna Museet.

AMc: Do you hand-draw your cartoons? I read that you have been exploring working with computerised jacquard looms.

KS: These all come from prints I made – lithographs – of all different things I used on and off for 20 years. I collage them together to make the layouts for the tapestries. But most of it is printmaking. Then I work with the publishers, Magnolia Editions. They scan my drawings, which are mostly at scale, then send me back digital prints, and I paint on the digital prints. We work like that. So, I think, in the exhibition in Malmö, maybe one of them is the original and the others are digital. I can’t really remember. It’s such a transformation between the original collage and the tapestry. I teach, so, in a way, I like making things very didactic, because I think it’s really good for students to understand the processes involved, and that each process can have its own integrity, but it keeps turning and changing and mutating into something else. That’s something I’m always trying to instil in the students: things take time, they evolve over time, and they need that time to reveal themselves.

AMc: You mentioned reworking the same image or theme. How do you conceive of a new work? Do you get an idea of a motif or a story first, or the desire to work with a certain medium, or to continue with a theme you started but didn’t exhaust? What comes first and how do you develop that?

KS: In 1994, I did a residency at Massachusetts College of Art in Boston, and I went to the Peabody Museum at Harvard and drew. They have all these taxidermy animals, and I would go and draw them and then make them into photo-etchings and photolithographies. I have tons and tons of images, and I have been working with these same images since 1994. I generated a lot of paper. I take them out periodically and collage them together, and then they change in various ways.

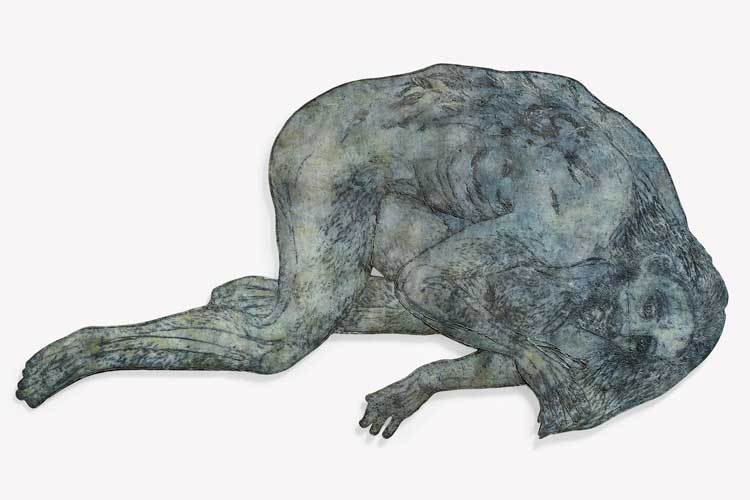

Actually, there was a sculpture that was supposed to be in the exhibition – it isn’t because it wouldn’t fit in the elevator – called Rapture, which is a woman coming out of a wolf, and that comes exactly from the wolf I drew in 1994 and a woman that I drew some other time in the 90s. Then I just chop. I make drawings by chopping them up and reconfiguring them. I also do that with sculptures. I make wax sculptures, and then I cut them up and reconfigure them so that the person is doing different things, or the animal is in a different position. I made sculptures of that same woman and animal, and then I just turned it upside down and opened it up.

Kiki Smith, Woman with Wolf, 2003. Photo: Kerry Ryan McFate. Courtesy Pace Gallery.

AMc: Is all this done purely from an aesthetic point of view, or do you have meanings attached to the different animals and characters?

KS: Sure. Things hold meaning as ideas. Not as images, but as ideas. A rabbit or a wolf or a mouse – they have tons of meaning that swirls about them. I use them because they hold meaning, but the meaning isn’t fixed. It’s elusive, and it changes over time, and it changes with the knowledge you have about the symbolic meaning or the cultural meanings of animals or whatever. Things resonate. That’s why objects engage us, because they resonate with different associative things. It’s not like there’s any fixed agenda in it. It’s just meandering around. You also might forget why something seemed very apparent to you at one point, because it just goes away.

AMc: Is meaning never fixed?

KS: No, I don’t think so. It’s like the wind. It’s just thoughts. It comes and goes.

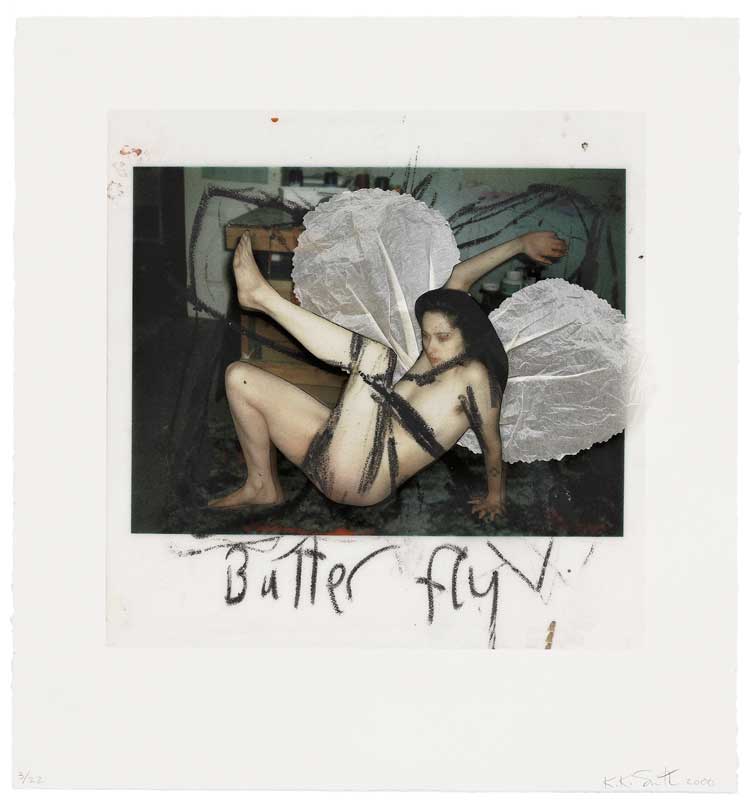

Kiki Smith, ButterRy, Bat, Turtle, 2000. Photo: Courtesy the artist and Pace Prints.

AMc: The exhibition looks at the relationship between human, animal and nature. Can you expand on this? What is your creation myth? What do you believe about the origins of the world and humanity?

KS: I have no idea about creation. We’re here temporarily. But how we got here or didn’t get here, I don’t have much of a clue. I don’t have any big cosmology beliefs or anything. We’re just here at the moment and we – animals and us – are all in very precarious states right now. We’re making our state more and more precarious every day. You see that there have been tremendous shifts in what was living on this planet between other times and now. We might also just be specks in time. But I don’t have any big ideas about any of that. I don’t know.

AMc: Do you worry about what happens next?

KS: I think we’re in tremendously treacherous times. The uncaringness that people show to one another and the collective uncaring of everything is so profound.

Kiki Smith, Fallen, 2018. Photo: Phoebe d' Heurle, courtesy of Pace Gallery.

AMc: You’ve said before that “if you can avoid extreme anything, it’s probably better”. What reaction do you want people to have to your work? Do you not therefore seek to provoke?

KS: I don’t. I just make things because I like to make things, and I like looking at them for a while after. I really like the experience of making things. It’s a language of communication. Artists are always trying to reveal themselves and remain hidden at the same time. It’s the space in between. And what I think about things is just my own personal predilection for thinking about things in weird ways. For art to function in any way, it has to have enough open space in it, so that people can find their own meaning or have their own experience. I don’t want people in my experience of it. I’m drawn or attracted to things, and I have the energy to pay attention to them, but I don’t have a desire for other people to think a particular way or anything like that. My work isn’t that didactic. It can only survive if it has enough in it to take care of itself; that other people find it engaging one way or another. I don’t want people to think anything particular.

AMc: Do you want people to spend as much time with your work as you have spent making it, because it’s often a very painstaking process for you, isn’t it?

KS: No. It depends. Mostly, you get an idea for a split second. It’s not even an idea. It’s just something that tells you what to do, or you have got something in your head, and then you start working on it. It can change radically over time, because other bits of information come to you and get added. It’s like a snowball rolling or something. But, you know, a lot of making art is ridiculously monotonous. Some things aren’t so much work, and some things are tedious. But I think that’s a big attraction for artists, that it frees you. Being attentive to something else for long periods gives you some freedom from yourself.

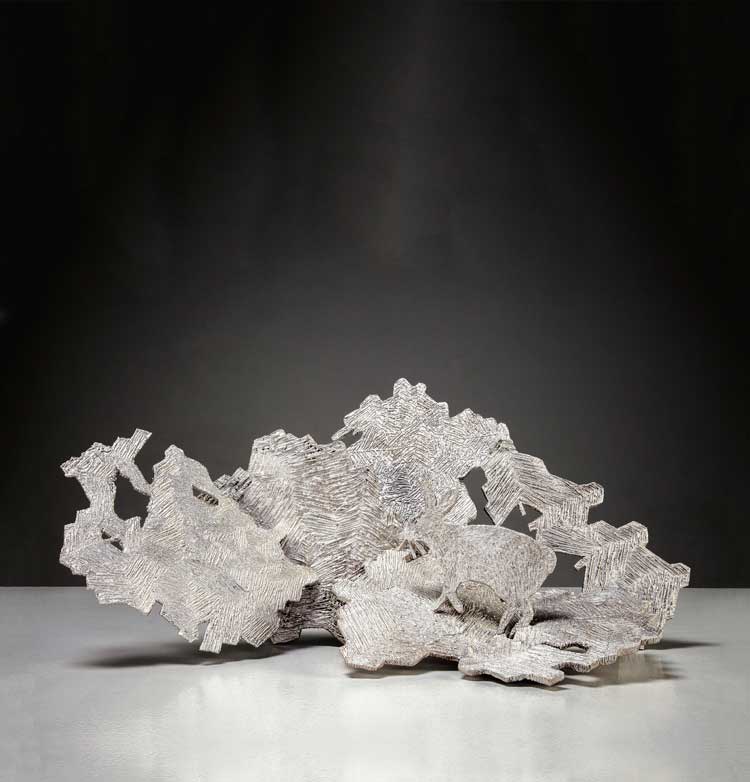

Kiki Smith, Hoarfrost, 2014. Courtesy of Pace Gallery.

I feel extremely grateful for having been able to exhibit my work. I enjoy making constellations of exhibitions. I always say it’s like doll’s houses – you’re arranging furniture and thinking about what goes where. It’s like playing with words or space and meaning. I am very grateful that I have been able to support myself for the last 45 years making work. Maybe it was too possible for me to make work. It might have been a little better if I had less possibility. But I’m somebody who has to make lots of in-between things. I have some friends who make one thing every five years, and it’s astounding. But I can’t do that. I have to make a whole bunch of different experiences, because they turn into other weird things that you’re not expecting. And that’s what is exciting about being an artist – that you have no idea where it’s going. You have to trust what you’re doing, but you don’t have any idea where you’re going with it.

AMc: Do you ever go the wrong way and then regret something you have done?

KS: No, I don’t think there are any wrong ways. Sometimes, I destroy half of what I have done. But no, because everything teaches you something. Hopefully, you learn from what you’re doing, and that brings you to a new place. I have been very fortunate to work with other people – to work with printmakers and in foundries – and in all those situations you learn. And it’s very exciting to learn.

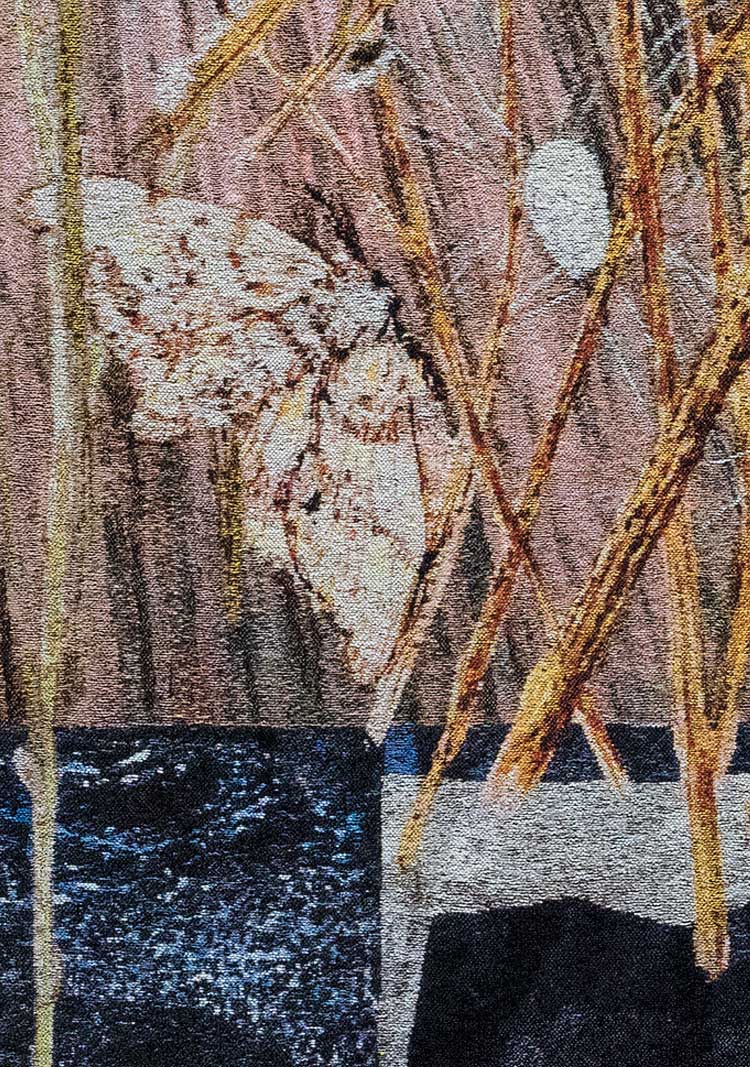

Kiki Smith, Spinners (detail), 2014. Photo: Courtesy Magnolia Editions, Oakland, CA.

AMc: How do you feel about digitisation and things such as artificial intelligence?

KS: I don’t know so much about AI, but I think digital things are there as a tool. All nature is very technological; it’s a very big component of how we are organised here on Earth. The tools change all the time, and it can lead to new ways of working. There are lots of things I love about being able to digitally print waxes now, to make something at this scale and then make it larger and print it out. Then you have to futz with it to make it a little more your own again. Certainly, with the tapestries, I’m working with digital printouts all the time, and then I paint on them, and we rescan them. Tapestries are about 25dpi, and you’re working at about 300dpi or higher, so you get to do everything in a very exact way, and it comes out very amorphous and different, but it works. It’s interesting. All those things are very interesting. Technology is just a part of us. I like making things by hand, but making things by hand or not doesn’t make things better or worse. The work has to be what’s engaging, not how it was made. And, at the same time, too, you know, we’re all limited. We’re all just one little part of the whole. It’s not like you can contain all of creativity or something. You just have one little slight insight. I think art is something that has the potential to always be creating space in society, creating more space. Societies tend to be restrictive, whereas humans are much more infinite, and life is much more infinite, and art is a vehicle for seeing that we have a much larger capacity than what we present in our daily lives.

Kiki Smith, Eagle in the Pines, 2016. Photo: Tom Barratt. Courtesy Pace Gallery.

AMc: Is that why you have previously worked a lot with taking the body out of its skin?

KS: I was interested in learning what things mean to you. What does the skeletal system mean to you? What are all the associations you have if you think about skeletons or if you think about skin? It’s fascinating to me, and I think art is often just a vehicle for people to learn about things. Many people’s work is very linearly about learning. Mine is a little more amorphous, but a lot of the time it is just about learning about different systems or how things are made or how they combine. It’s a lot about listening and then paying attention. And you are constantly being inspired by other artists’ work, and by your own work, and it keeps changing and moving around. There are points where it all falls apart, and you get good at something and realise it’s not interesting at all. Then you have to wait until you find some aspect of it that you don’t know anything about. And then you can find something new in things. I think art is also about enjoying the unknown. Just seeing what happens.

AMc: Do you know what you are going to work on each morning when you go to the studio, or does it very much depend on how you feel when you get there?

KS: I get there and see what I feel like. I have projects I am working on. Today, I’m making these little waxes for a sculpture. I already have the cast pieces, but I don’t know where I put them, so I’m remaking them. I have to get that done. Then I made some prints, and I have to hand-colour them. I work in a way where I set something in motion and don't quite know where it’s going, and then it tells me what it needs. It keeps revealing itself. I have Virgo rising on my astrological chart, and Virgos are very methodical, task-oriented people. I think it really helps, being an artist, if you can move in an orderly direction. Sometimes, I’m working for exhibitions, but mostly I’m just working because something strikes me to do it. Then it begins to coalesce into a group of things, and then I see what is absent or what I would like to include. I’m just sitting here at my kitchen table working.

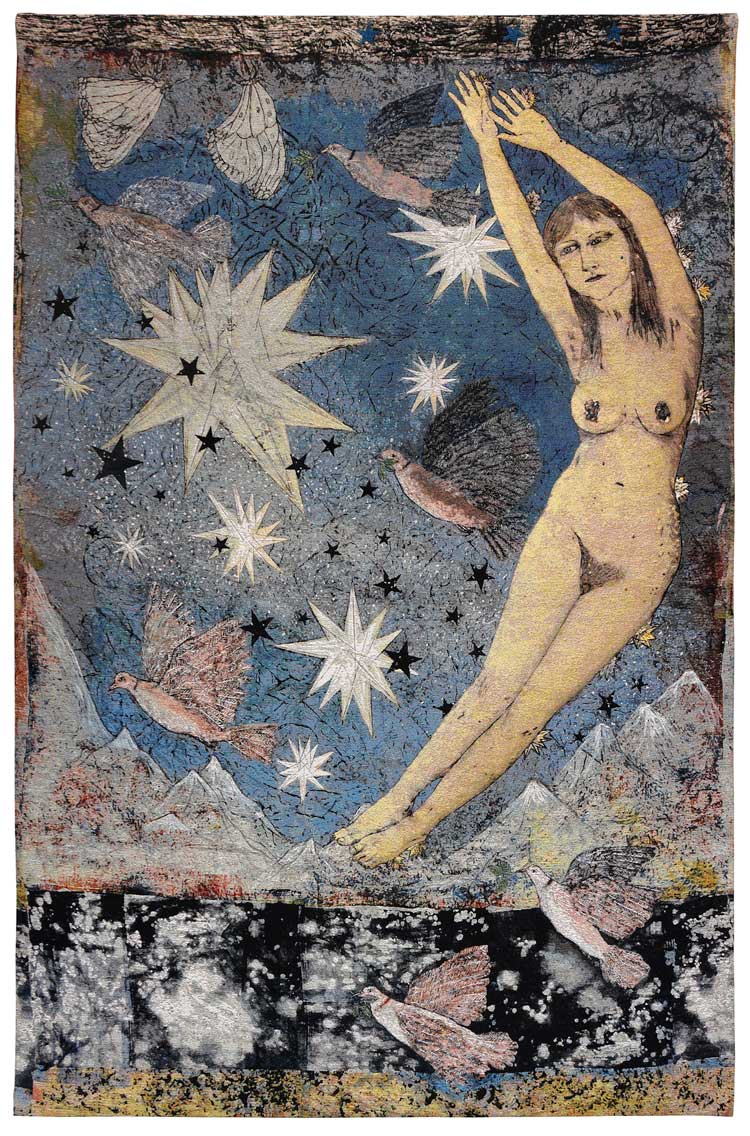

Kiki Smith, Sky, 2012. Photo: Courtesy Magnolia Editions, Oakland, CA.

I try to feel like my time is marching on, and if I want to finish certain things, I have to finish them. But certain things I don’t know how to finish, so they just drift in limbo for ever. But, for me, being orderly helps. Having deadlines helps sometimes, but sometimes you make things, and they don’t make any sense. And then, five or 10 years later, they make sense. I realise now that, when I was young, I was often making work that was myself in the future. And then, in the future, it fit. At the time it seemed totally incongruous, and then, all of a sudden, it was very apparent that that’s where I had been going. I’m not trying to get anywhere. It’s always just a meandering. But, at the same time, I’m 71, so if I want to do something, I had better do it today, because you don’t know what’s coming. When you’re young, everything can wait. But now I try to get things in order. I try to get rid of all the excess in my life. But that will take another 20 years.

AMc: Is there anything big you want to achieve or complete in your life?

KS: Not really. I would like to have big ideas, but I don’t. I’m not somebody who has big, ambitious ideas. I would like to make windows for a chapel, and I would like to learn to use colour more and to use stained glass. Most of my work has very little colour in it. I think that’s why I started making tapestries, because I had this idea that tapestries have colour. I thought that was an opportunity for me. When I was young, I used colour, and then I stopped for about 30-something years.

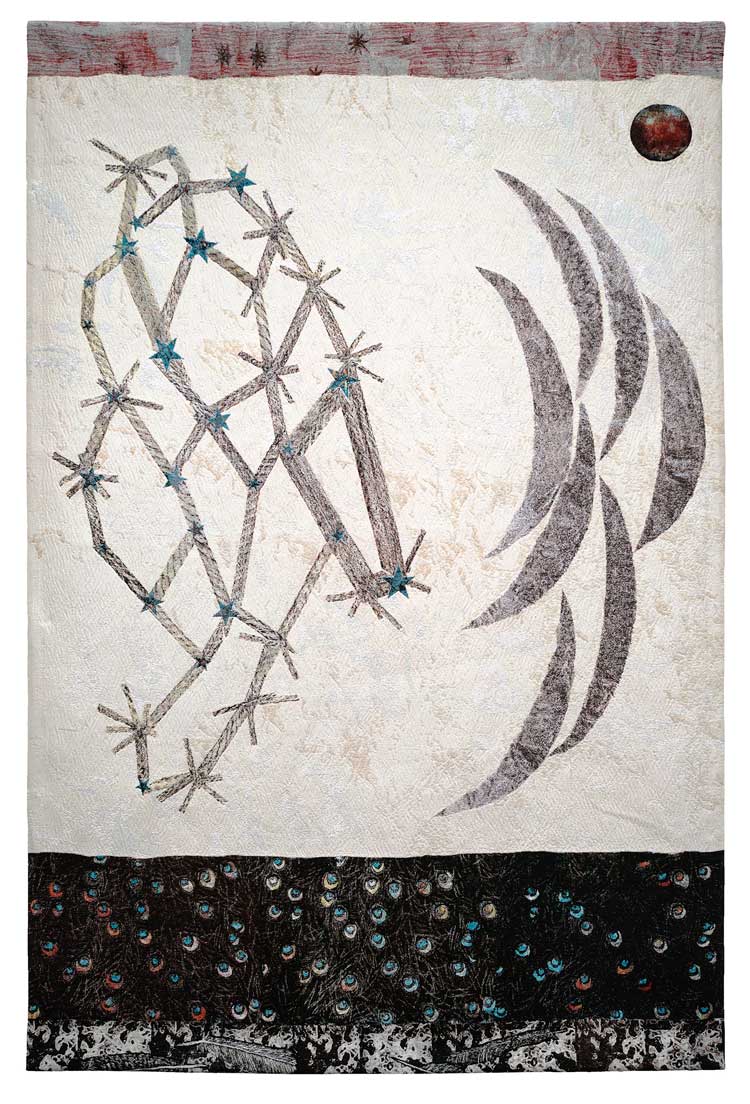

Kiki Smith, Visitor, 2015. Photo: Courtesy Magnolia Editions, Oakland, CA.

I would like to learn more about colour, because I really like it a lot. I just don’t know what to do with it. I want to have more experiences than I have time for. I’m trying to finish work, and I have to be very diligent now to finish it. But it’s on its own terms. That’s the thing. You think you’re making one thing, and then it turns out to be totally different. I don’t have that much control over it, and nor do I want to be in control of it. I’m not interested in that. I’m more interested in letting things reveal themselves, because they’re much larger than my consciousness and my experience. That’s what I like the most – that everything’s very unexpected in life. There are many things I would really prefer to have skipped, but then there are other things that life brings you that are so much larger than you could ever have imagined. I wasn’t raised to have an idea about how I should be living or to want much of anything. I want to finish these wax bits today, or I’ll go crazy tomorrow. Then I’ll set to work on hand-colouring my 125 prints. I’d like to have everything in order in my house, but the rest of life will take care of itself.

• Kiki Smith: Woven Worlds is at Moderna Museet, Malmö, until 12 October 2025.