by MK PALOMAR

The artist, animated film-maker and curator Birgitta Hosea (b1965, Edinburgh) began her creative practice in film and drama while she was still at Glasgow University, before pursuing theatre design at Glasgow School of Art. Even at this early stage, Hosea was keen to push boundaries and explore the possibilities of cross-disciplinary practice. She later stepped sideways to undertake a course in computing and fine art, followed by an MA in digital imaging and animation, and these diverse disciplines have formed the bedrock on which she has built her expanded-animation practice. Hosea synthesised all these creative fields in her interdisciplinary-practice-based PhD (completed in 2012), at Central Saint Martins, on animation as a form of performance.

Hosea has had frequent invitations to exhibit her work, deliver presentations at conferences and teach and supervise PhD students at institutions across the world. She has been artist in residence at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, Yarat Contemporary Art Space in Azerbaijan and the Centre for Drawing at Wimbledon College of Arts. She wrote and directed the MA course in character animation at Central Saint Martins from 2000 to 2015 while conducting research into animation as a form of performance, and then directed the Animation Department at the Royal College of Art from 2016 to 2018. She is now a visiting professor at Chengdu University in Sichuan Province, China, and a reader in moving image at the University for the Creative Arts in Farnham, Surrey, working with new technologies for storytelling, expanded animation and performance drawing.

Studio International visited Hosea in her studio in east London to talk about her creative practice and her solo exhibition Erasure currently showing at Hanmi Gallery Seoul.

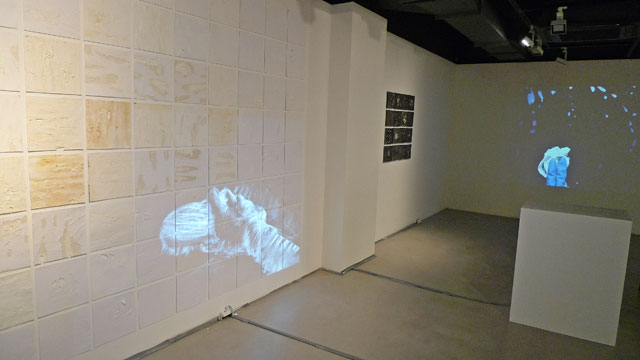

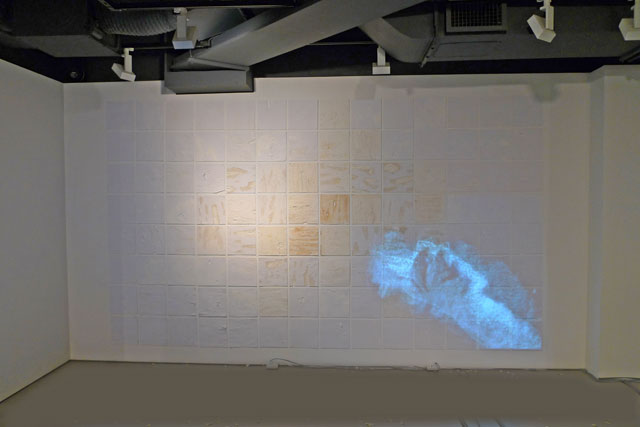

Birgitta Hosea, Erasure, installation view, Hanmi Gallery, Seoul, 2018.

MK Palomar: Practitioners find their path in various ways. When you were young, did you have any visual artwork around you that inspired your creativity?

Birgitta Hosea: When I was young, my parents didn’t have a television, so I used to spend my time making toys and clothes with my mother. My mother has always painted and there were a a number of craftspeople and artists in her family, including her uncle, a Swedish artist called Tor Ivar, who studied with Fernand Léger in Paris. We used to visit Tor Ivar in his studio when I was a child. He used to give me a picture every time I visited him, or a print or a drawing. It was really special.

MKP: And did that inspire you to make images?

BH: I was always drawing with my mother, and making things with my mother. We made all our own clothes and toys, houses in the garden, clothes for dolls or my Teddy (laughs).

MKP: As an undergraduate, you studied film and drama at Glasgow University, then, later, theatre design at Glasgow School of Art. How did these subjects lead you towards animation?

BH: In the beginning, I was very interested in acting. I was involved in theatre groups, I set up a women’s theatre co-operative and I was in a punk band for a while. Then, after that, I began to get more interested in the visual side of things rather than being on stage myself, and I started to work in theatre design. I designed for performances of different kinds. I used to work on films and pop videos and adverts and theatre shows. It couldn’t find a job in Scotland after I graduated, so I came to London. I’m an economic migrant.

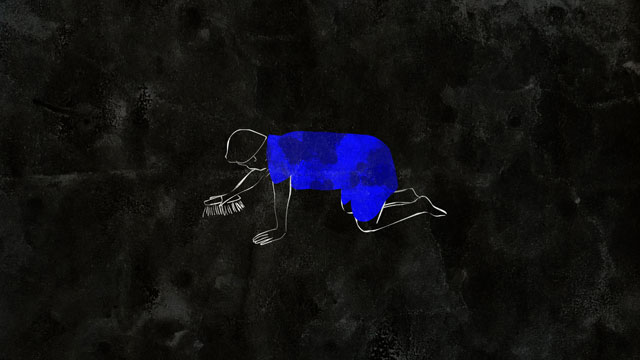

Birgitta Hosea, Erasure, film still, 2017.

MKP: What sort of film productions did you work on?

BH: The first film I came down here to work on was Ken Russell’s The Lair of the White Worm – I was the art department assistant. The production designer, Anne Tilby, was amazing. I learned so much from her. I used to go around buying props, taking Polaroid photos of things, making scale drawings and models of things, making props and faxing drawings to her. So, I was doing art department design research, really. I also made a 21-ft long, quilted silk dragon (laughs), which they used for a party scene with lots of people inside the dragon.

MKP: What did you do next, after Ken Russell’s The Lair of the White Worm?

BH: I did so many jobs for different companies that were making props. I did props for Zeffirelli’s Hamlet and for a couple of the Indiana Jones films. I was assistant designer for Julian Clary’s TV shows, so I used to make some of the costumes and the props, and I worked on a number of pop videos for different bands that no one now would have heard of (laughs), and commercials. And then I started to do design in my own right, so that was more fringe theatre, low-budget pop videos and short films.

MKP: That’s an extraordinary collection of experiences. What led you to take the next step towards computers and animation?

BH: When I first got to London, I was doing all these jobs of making things to make money, and I was also involved, first of all with the Brixton Artists Collective, and then various other projects and I started getting interested in installation and exhibiting my soft sculpture works, with a show called Hot Pussy in 1993. I was working for the [HIV and sexual health charity] Terrence Higgins Trust as a volunteer. I was quite involved with Aids activism: we made a carnival float (among other things) and, as part of my volunteering, I learned a computer program in the office called WordStar.

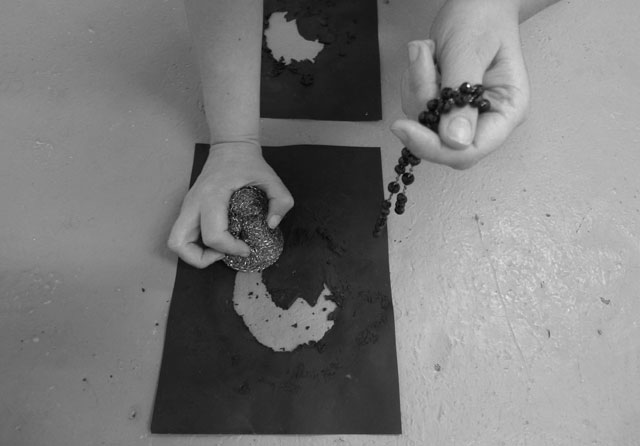

Birgitta Hosea. Rosary Drawing XII, 2015. Paper, 29.7 x 21cm. Remnant left behind after performance.

MKP: What year was that?

BH: Around 1993. Very early [in home-computer terms]. So, I learnt WordStar and, at the time, you would get community centres that might have one computer you could hire for an hour at a time, or a cyber cafe that you could go to. So I started to go to those places and I began to think: “Oh, I’m quite interested in this.”

MKP: What was it about it that interested you?

BH: It was just fascinating to learn a new thing, and I thought it would be good for me as a theatre designer/film designer to do presentation drawings for clients. It would be a way for me to make really professional-looking visualisations of what the designs would be. And perhaps I would go into doing sets for computer games. Computer games were just starting: they were more like arcade games and I was thinking maybe you could visualise set designs for films or theatre in the three-dimensional space within the computer, and that would be good for my career as a designer. Working then was really precarious: it’s like now with zero-hours contracts. The freelance work was up and down: famine or feast; lots of work or no work. Then, at an interview at the jobcentre, actually, they suggested I go to college. So, I went to Tower Hamlets College and did a foundation course in computing and fine art and that was amazing. Andrew Greaves, the tutor who ran it, had been in the London Film Makers Co-Op, and he was quietly pioneering in making installation art and then making that digital. He was very inspiring and made me want to take it further. It brought together everything I’d done before – three-dimensional design, two-dimensional design, drawing, performance, photography, video – everything came together in the computer.

MKP: I’m going to jump ahead slightly. Reading through your various biographies online, it seems that your creative practice has often been – in one way or another – linked to the screen. Yet you continue to make live performances.

BH: In a way, yes. I’ve often thought that, in designing for theatre, you’re thinking about the framing device of the proscenium arch – when you’re looking on to a stage in a classical theatre, you’re looking on to a rectangle that frames the stage, so a lot of the time I’m connecting that to the screen rectangle, so it’s a spatial practice that’s translated on to a rectangle (screen). There’s a spatial aspect and a liveness that I enjoy about performance and creating moving image can be a spatial practice that’s translated on to a rectangle ( screen).

MKP: How does live work inform your screen-based practice?

BH: As I said, I have been working with different forms of performance for a long time now. I think there’s something exciting about the spontaneity, the atmosphere of something being unique and people being gathered together in one place, and you have to be there to experience it for yourself.

Birgitta Hosea, Erasure, installation view, Hanmi Gallery, Seoul, 2018.

MKP: And what about the performance? What experience do you have?

BH: For me, my presence is a material – that’s how I see it. My actual physical presence is a material and my energy and the actions I can make, are some of the materials that I have at my disposal when I make a piece of work.

MKP: How is that different from making a piece of work in your studio?

BH: I think it’s different because of the people watching and the energy they give you and how you take on that energy. It’s a two-way process. And there’s an element of danger when it’s live. It’s a bit more risky – anything could go wrong, I feel that I push myself more if I do something live.

MKP: You did the computing and fine art foundation course at Tower Hamlets, so can you tell us, how did you get from there to doing a PhD in animation and performance at Central Saint Martins?

BH: I felt I was a jack of all trades: I’d had this career in design for performance, working on the creation of sculptural objects and spatial environments that were translated on to a rectangular screen. I had also started to make installations, because I was interested in the experience of space. But then I changed direction to learn computer animation – and people were giving me work because I had learned how to do computer animation at a time when not many people knew how to do it, and I was getting a lot of demands for training and doing graphics for people. I was training people in the BBC and other broadcasting companies in how to use software. I was demonstrating software. I was getting jobs to do motion graphics. I did a lot of work for Adobe. I was excited by this new medium, I was excited by learning something new and, as I said, it had brought together everything that I’d done before. I found it inspiring and exhilarating and spent quite a few years as a complete nerd – all my time was spent learning things about software.

I did an MA in computer imaging and animation at London Guildhall University [now London Metropolitan University], then went to teach at Westminster Kingsway College of further education, and then Central Saint Martins. The animation course (at Central Saint Martins) had been run by the graphic designer Val Palmer and was initially a very vocational, skill-focused course; so I tried to make it more conceptual and develop it more. And, as I said, I felt at times that I was a jack of all trades, who had learned one trade and then gone into a different one and was a master of none, but with my PhD, it made me feel that, actually, my expertise could be where these two areas met.

MKP: And can you talk to us about your PhD – what was it focused on?

BH: In my PhD, I looked at whether animation could be conceptualised as a form of performance. People think of animation as something for children, and not really worthy of much attention, or they used to. I was thinking more of the act of the animator – are they performing through the character that they are drawing or sculpting (like a form of puppetry)? I was also looking at whether animation can be live, Does it need to be prerecorded? Is it possible to be spontaneous in the moment? Also, I was looking at whether the animation is actually in the mind of the viewer – is it the viewer who completes the animation? Is it the viewer who is actually animating the work? These are the sorts of things I was looking at.

MKP: Where did that take you?

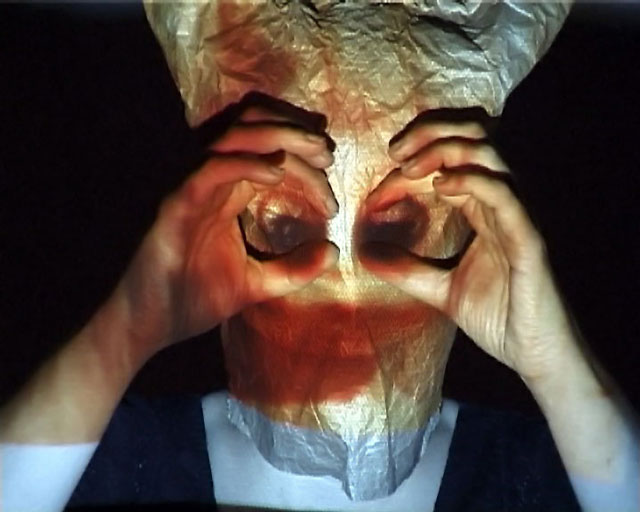

BH: New York. I started to experiment with myself as the animator, performing animation live and also being animated by animation. I made a performance called Out There in the Dark, which was based on some lines from the film Sunset Boulevard, and I made an animation with a doll speaking a couple of iconic lines from the film that, for me, really said something about women performing for the camera. The lines were looped and cut up, and then I put a paper bag on my head and replaced my face with a projection of this animated doll’s head, and performed repetitive gestures from the film.

Birgitta Hosea, Out There in the Dark, 2008. Performance with projected animation , dimension variable, looped duration varies. From the first performance in the Lethaby Gallery, Central Saint Martins, London, 2008.

MKP: Is feminism and gender important in your practice?

BH: I can’t avoid gender being important in my practice, because I am female; it’s not always consciously something that I’m doing, but it is always there.

MKP: UCA’s online information about you tells us that you are currently working with expanded animation and performance drawing. Is the work Out There in the Dark, which you did in the US, expanded animation or performance drawing?

BH: The term “expanded animation” is a development of the term “expanded cinema”, which is the idea of taking a film (or, in my case, an animation), out of the flat screen and showing it in different contexts, and experimenting with the means of viewing and the means of presentation.

MKP: And what is performance drawing in relation to expanded animation?

BH: I think there’s an intersection between the two because I’m interested in live animation and whether animation can be created in a live situation – does it always have to be prerecorded? So, for me, there’s a crossover between live animation and performance drawing. Or a meeting point is perhaps a better term than crossover.

MKP: Can you tell us what you think performance drawing is?

BH: A performance drawing is a drawing that’s performed in front of the beholder in a live situation, so you’re seeing a becoming and unfolding rather than a finished item, and that process [being revealed to the audience] really interests me.

Birgitta Hosea, Erasure, installation view, Hanmi Gallery, Seoul, 2018.

MKP: That leads us to your exhibitionErasure, currently on show in Seoul. It includes sequential drawings, animation, projection and live performance. Can you tell us how you undertake research for your creative practice, and the concepts behind the works in this exhibition?

BH: For this exhibition, the whole process started out with a residency that I did in a former convent in Italy. I wanted to challenge myself and not to bring any familiar crutches or familiar ways of working: I didn’t know what I was going to do there. My grandmother had recently died and, because the residency was in a convent, I brought her broken rosary that I’d found among her possessions when she died. I wasn’t brought up religiously, so the Catholic religion of my mother’s family is a bit of a mystery to me. I didn’t know how you use a rosary, or what it’s for. So, every day for two weeks I drew this rosary, and I also visited the local church and watched the women using rosaries and asked people questions about it. I made different sorts of drawings of the rosary, with all kinds of materials and techniques.

Birgitta Hosea. Rosary Drawing XII, 2015. Photograph, 29.7 x 21cm. Documentation of performance at 51% Remember Her exhibition, Tower Gallery, London, 2017.

Every day for two weeks constantly, I was drawing this broken string of black beads. As I was drawing, I thought a lot about both of my grandmothers, and I particularly thought about Catholic women and how they struggle, and how their own sense of self or life is sacrificed for their families and they work really hard and this is never recognised. It’s taken for granted. And then I started to think – can I make a drawing of this rosary with actions that capture this struggle and that oppression [that those women have experienced]? Can I do a drawing in a manner that reflects the actions that I feel reveal the oppression of these women?

Birgitta Hosea. Rosary Drawing XII, 2015. Photograph, 29.7 x 21cm. Documentation of performance at 51% Remember Her exhibition, Tower Gallery, London, 2017.

I thought perhaps I could make a drawing through scrubbing and cleaning products, so I got these metal [wire wool] scourers and bleach and started experimenting. I started scrubbing with the wire wool on sheets of black paper, one by one, and it left a hole behind that looked like the highlight on the black (rosary) beads that have been shining. And as I scrubbed and scrubbed and scrubbed and left a trail – I did one sheet for each bead – I thought: “Oh, my, the trail of paper is like a filmstrip. This is an animation of a different kind, and actually the rosary is like a filmstrip, because it’s recording all these actions, all these prayers on one strip of beads.” I was astounded by this flash of illumination that I’d had, and that’s where Rosary Drawing XII (in my Erasure exhibition) comes from, because it was the 12th drawing in the series. In the exhibition, I’ve got photographs from previous performances on the wall, I’ve got some of the black papers left behind installed on the wall in a row like a giant film strip, and I did the performance at the opening private view.

Birgitta Hosea. Rosary Drawing XII, 2015. Photograph, 29.7 x 21cm. Documentation of performance at 51% Remember Her exhibition, Tower Gallery, London, 2017.

MKP: And in your exhibition you also have projections on installations?

BH: Yes, so this work made me start to think aboutthe invisibility of labour. It made me start to think about all the labour that some people do that just disappears into the ether. We see an end product, but we don’t see the process of the labour so I thought about how I could capture this act of labour. So, in Rosary Drawing XII, I’m literally scrubbing, scrubbing, scrubbing, and the inscription of my scrubbing is recorded on this series of black sheets of paper. You see my labour captured in these pieces of paper – it’s quite clear. Then I started making other works with cleaning products and scrubbing of different kinds. Rosary Drawing XII was a breakthrough piece for me.

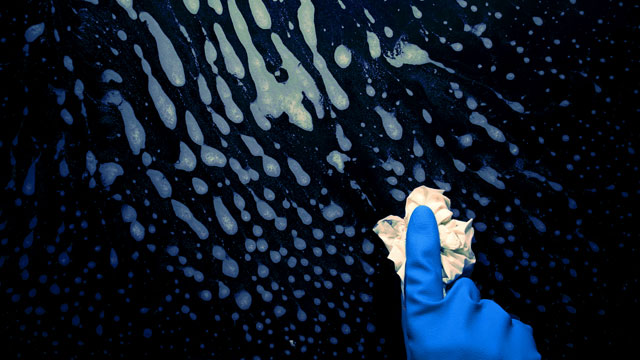

Birgitta Hosea, Erasure, film still, 2017. Window cleaner, bleach, fullers earth, ink, stop motion and digital animation, 3 min.

MKP: In your exhibition, you have a film titled Erasure. Is the film a documentation of your live performance work?

BH: No, I was asked to make a piece of work for the Venice Biennale for an exhibition of artists’ films called Empire II and the theme was anxiety. So, because I’d done all this work about cleaning, I thought why don’t I make a film about compulsively cleaning, so that was how Erasure came about.

[Hosea shows me her personal copy of the film Erasure (on her laptop). I see bubbles of liquid floating across the screen, and a blue-gloved hand rubbing away the liquid with a cloth. With each motion is a squeaky sound of cloth smearing over wet glass.]

Birgitta Hosea, Erasure, film still, 2017.

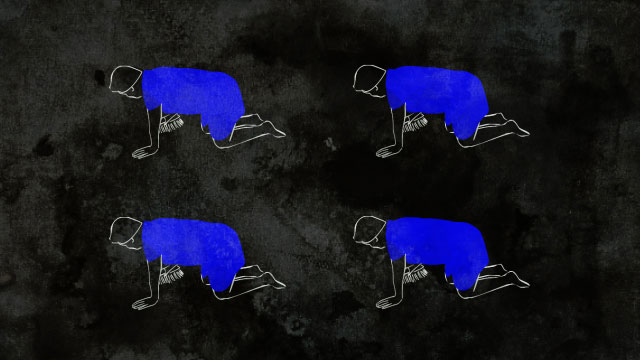

So, this is animated Windolene [a cleaning product], which I did at the Royal College of Art on its multiplane camera – a piece of equipment with multiple sheets of glass and a camera at the top. It’s old-fashioned animation equipment that Disney would have used. It’s animated on glass sheets, and I used rotoscoping to animate my figure – so, it’s an animated version of video referenced from my own performance. My hand rubbing is shot frame by frame on glass to get the patterns of the Windolene. Jose Macabra is an amazing sound artist I know who made this extraordinary frenetic, anxious sound track forErasure. The film has been in the touring exhibition Empire II, which as well as exhibiting at the Venice Biennale, has been at Art Brussels, Tallinn Art Week in Estonia and a number of galleries in Europe and Britain. It’s going to the Oaxaca Museum of Contemporary art in Mexico next February. It’s being distributed by a film company now, Fabulosis Films, so I’m not permitted to share it online, but you can access a trailer of it online.1

MKP: Can you talk about why it’s important for you to combine objects and digital technology – for instance installations with projections on, in your exhibitions?

BH: I was interested in creating a whole spatial experience. It was great to have an opportunity to put together all this work that I’d been doing and realise it had connections. I did lots of work in planning how all the things would fit together in the space, conceptualising that, bringing in theatre design and so on.

MKP: There are four Post-it notes on the wall of your studio: the first says “Invisibility of labour”; the second says “Compulsive hysterical OCD”; the third says “Recording physical action”: and the last one says “Erasure is mark-making”.

BH: They were “notes to self” while I was making it all.

MKP: So, those components all fed into your exhibition?

BH: Yes.

MKP: Recording physical action is documentation, it’s not live – yet motion always implies something live?

BH: I did a live performance at the exhibition, as I described earlier, Rosary Drawing XII. The pieces of black paper are along the wall. I did a performance underneath them on the floor with a metal bowl filled with water and a metal scourer. And when I finished, they left the trail of pieces of paper there, the metal bowl with the water in and all the black muck from the paper, and the scourer covered in black muck. So, you saw the aftermath. You’ve got photographs of the previous performance on the wall, you’ve got the images that are the residue, the aftermath, and then you’ve got a literal trace of a performance left in the gallery.

MKP: So, on one wall in the gallery, there is the film – and you have just described how you made it. On another wall in the gallery, you have a series of drawings and a projection on top of them of a drawn version of your animated hand-scrubbing. There is a sort of element of surprise and unexpected in this mixture of materials and processes. Would you say there is something to do with the uncanny in your work?

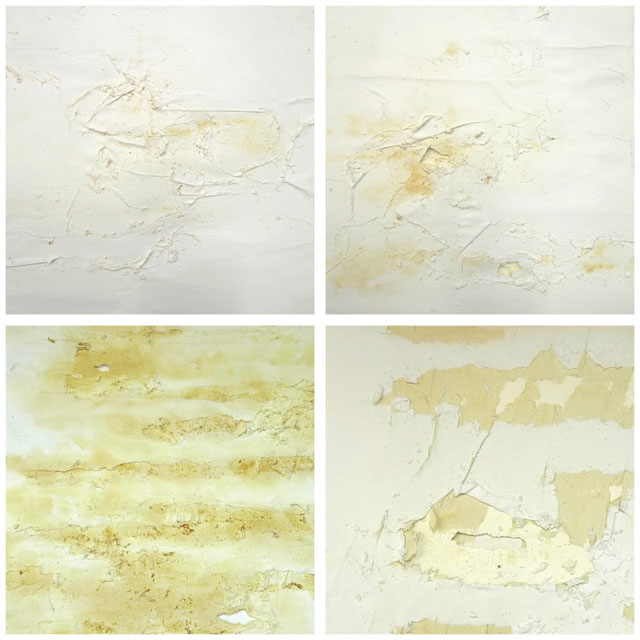

BH: Maybe there is some kind of ghostliness. This [set of drawings on the gallery wall] is 112 panels [made to fit the gallery space]. I’ve made them by scrubbing [layers of stretched paper] with bleach and bicarbonate of soda and flour, and building them up in layers … and the sound is very important … In the exhibition, I like the way the squares visually echo the squares and the scrubbing echoes the scrubbing …

Birgitta Hosea. Scrubbed Clean, 2018. Bleach, Cif, bicarbonate of soda and flour on paper with projected animation, 260 x 470 cm. Installation view.

MKP: So, this is white paper that you’ve painted on?

BH: No, I haven’t painted them. I’ve stretched layers of paper on top of each other and then scrubbed it in different ways. In the middle [of the group of drawings], the panels are more yellow in colour, and then, around the edges, they are more white. The colour depends on the differences in the solvent and the paper. Some of the paper was creamy, some was white.

Birgitta Hosea. Scrubbed Clean, 2018 (detail). Bleach, Cif, bicarbonate of soda and flour on paper with projected animation, 260 x 470 cm. Installation view.

MKP: I’m holding one of your pieces of layered paper – a trial left in your studio – and it has been distressed and rubbed and scrubbed and looks to me like a piece of old wall where the plaster has crumbled off, leaving layers of paper and previous plaster exposed. And the scrubbing brush you used is completely caked in white pulped paper. They are both beautiful objects.

BH: I drew my hand in charcoal holding that brush while scrubbing – and that was the model for the animated hand that’s projected over the layers of paper that I did rub with that brush.

MKP: So, you’re consciously switching dimensions and medias, and mixing up disciplines and materials … it’s engagingly edgy and brings me back to that element of visual surprise I see in your work.

BH: Yes, I’m jumping between disciplines in a way that frightens people sometimes. It confuses people and they sometimes find it strange … the sound is also very important. I don’t know that I mean it to be visually unexpected, but I am interested in the labour and I’m interested in this hand that is scrubbing for ever and ever and can never make the wall clean – like the miller’s daughter doomed to spin straw into gold in Rumpelstiltskin , just carrying on and on and on – endless labour … and I like the way that it is not constrained by a frame, but roams across the wall.

MKP: Having completed this exhibition in Seoul, what are you working on now?

BH: I’ve been thinking a lot about these questions of cross-disciplinary expanded animation, performance, cinema, animation and how it all fits together. And sometimes I conceptualise my practice as post-animation, because I’m not actually making animations very often, but I’m inspired by the idea of recording movement and recording actions. I’m looking at other ways to capture and record motion and time – so, I sometimes call my work post-animation.

I’ve been researching the history of expanded cinema and getting some experience from the text, and I’m very interested in a concept called paracinema. It includes works by Anthony McCall and VALIE EXPORT. They have made works about cinema, and they have called them film, but they don’t take a conventional form. So VALIE EXPORT has done things with light, mirrors and water and said: “This is a film.” And because she said it’s a film, it is a film, and she did that in the 1960s and 70s. I’ve been reading and researching in the British Artists’ Film and Video Study Collection about her and McCall, and I’m putting forward a presentation of my work and proposing it as a form of para-animation at Ars Electronica in Linz, a digital festival at which there’s a conference called Expanded Animation, and they’ve invited me to talk there. [Ars Electronica took place earlier this month.]

I’ve also got a commission in January 2019 at the Cello Factory in London, curated by [the digital art group] Genetic Moo. I’m going to be doing a participatory performance with laser pens, and I’ve also been commissioned by the Bill Douglas Cinema Museum, at the University of Exeter, as a visiting researcher. They’d like me to make a piece of art in response to their archives, which is very exciting. They have a collection of pre-cinematic technology, so I’m going to go and look through their boxes and make a piece of work in response to them. I used to find it problematic that I am multidisciplinary. I used to think I don’t know anything and I’m not in one discipline, but now I find it exciting – I’ve changed my thinking about that.

MKP: You’re also a Reader in Moving Image at the University for the Creative Arts in Farnham, Surrey. What does that involve?

BH: I’m developing the research culture, mentoring staff, putting on conferences and symposiums and applying for grants. I’m also going to be working on a multi-university, multi-institution Arts and Humanities Research Council research consortium on the future of storytelling. We’re going to be working with virtual reality and augmented reality, different technologies, and see how they can be used creatively to tell stories. I’ll be employed on that project for part of the week for the next five years, starting in September 2019.

Reference

• Erasure film online trailer: https://vimeo.com/ondemand/erasure

• Birgitta Hosea: Erasure is at the Hanmi Gallery in Seoul until 19 October 2018.