dsh: optimism is natural but a little excessive, 2025, installation view, TINA, London. Photo courtesy of TINA.

TINA, London

*6 December 2025 – 14 March 2026; **17 January – 14 February 2025

by BRONAĊ FERRAN

Since opening in late 2024, co-founded by Hana Noorali, Lynton Talbot and Tony Tremlett, the small commercial gallery TINA has been creating something of a frisson. Diverse visual arts exhibitions have been accompanied by live art and architectural sculptural interventions as well as occasional live music and poetry. It has also established its own “edition” for occasional publishing purposes. All this has situated it as a space of provisionality, fitting with its location, above a high-speed photo-print shop, close to the desultory edge where Soho fades into Oxford Street.

I am here to see Dom Sylvester Houédard: dsh – optimism is natural but a little excessive, an exhibition of typewritten works on paper by the postwar ecumenical and countercultural visionary, Benedictine monk and poet. The dsh in the exhibition’s title makes reference to the frequently used shortened version of Houédard’s name. Its subtitle is drawn from a title he made in 1971, shown here in the front room of the exhibition. Like many other works included, it is left to our imagination to decide and decipher, from the enigmatic clusters of lines, signs and symbols on the page, what there might be to be optimistic about and what exactly might be excessive about its highly constrained graphic elements. One senses that one is expected to cleanse one’s mind of all that is extraneous so as to allow this work to adequately permeate one’s inner psyche. At their best, Houédard’s works co-evolve in the eye of the viewer-reader, as if in a cybernetic loop between transmitter and receptor.

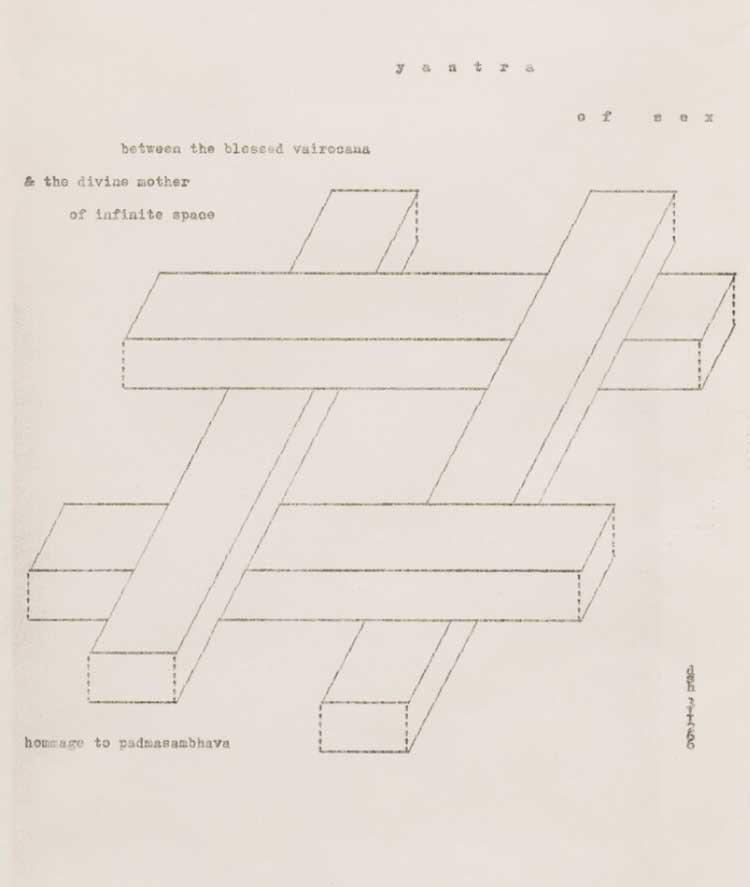

Dom Sylvester Houédard, yantra of sex, 1966. Typed page. Image courtesy of Lisson Gallery.

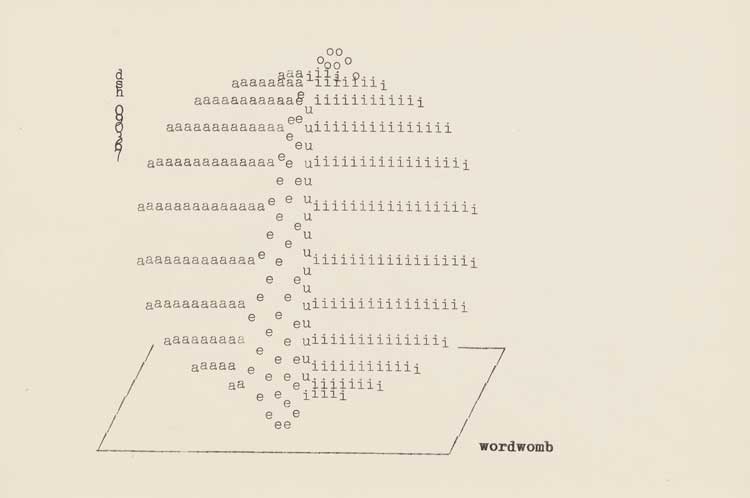

In the early 1960s, Houédard developed an idiosyncratic approach to language, which became, as the gallery puts it, a “fusion between poetry, typography and spiritual meditation”. His balancing of a seeming abstraction with a graphic precision within single sheet titles inspired their christening as “typestracts”by the Scottish poet Edwin Morgan. Much like the ritually infused aspects of Chinese calligraphy, where the language produced is often all in one motion, distilled and concentrated in time, so, too, in Houédard’s typestracts there is a sense of deep compression at work in his processes, where – at their most accomplished – every mark and its positioning appears to have come together in a unified wholeness. Across the range of 34 works being shown in this exhibition, several appear to me to achieve a near perfection in terms of his time-based, spatialist, autopoetic method.

dsh: optimism is natural but a little excessive, 2025, installation view, TINA, London. Photo courtesy of TINA.

As a multilinguist, who was also to the fore in terms of perceiving ways that western Christianity might find levels of synthesis with eastern religions, Houédard was known for heading off to London and Bristol from the contemplative Benedictine Prinknash Abbey in Gloucestershire and turning up at gallery openings wearing a flamboyant purple cloak and hanging out with other countercultural luminaries such as Bob Cobbing, Allen Ginsberg and David Medalla. He also corresponded with numerous figureheads of international postwar experimentalism. Houédard’s distinctive mode of writing prose was anticipatory of the shortened language of texting and tweeting; he was also one of the earliest cultural theorists to reflect on communication theory and its potential impact on language.

Aside from Cobbing, whose typographical approach to language was closely informed by his adherence to vocalised expression, Houédard was the first British-based poet to radically eschew the semantic basis of poetry in many of his titles. This was closely informed by his reading of works emerging in the previous decade from German language poets in particular, such as the ideogrammatic works of Dieter Roth, whose output from the mid to late 1950s anticipated a wider semiotic turn in concrete poetry in the decade that followed.

Dom Sylvester Houédard, wordwomb, 1967. Typed page, 16.3 x 20.2 cm (6 3/8 x 8 in). Image courtesy of Lisson Gallery.

As the TINA exhibition shows clearly, what then comes together within what Houédard was doing – using an Olivetti Lettera 22 typewriter sometimes late into the night in his monastic cell – was a singular combining of an enclosed spiritual hermeticism with a casting-off of language into domains of non-linear openness. We see this dialectical tension at play in many of the works here, which veer from what Noorali refers to as “an evacuation of language” to others in which a direct use of language is included, although its function is less one of explanatory meaning than a form of notational encoding, leaving the visual text open to multiple interpretations. Some – as with the works entitled Ba’al-shamem (1969) and The Two Nadis (1967) – point towards his profound interest in eastern thought and belief systems, showing us how, for Houédard, these references involved a transference of consciousness that then found form in what he was spontaneously producing.

These effects are also amplified here by an excellent curatorial decision not to overcrowd or pack too many of Houédard’s works together. We are invited to see some of the works singularly, while others are grouped into clusters. There are 34 works, dating from 1963 to 1972 – with the majority from 1971 (14), five from 1969 and 10 from 1967. As Noorali emphasises, Houédard was meticulous in documenting the precise date when each typestract was produced, allowing us now in retrospect to perceive shifts and subtle adaptations of focus from one decade to another.

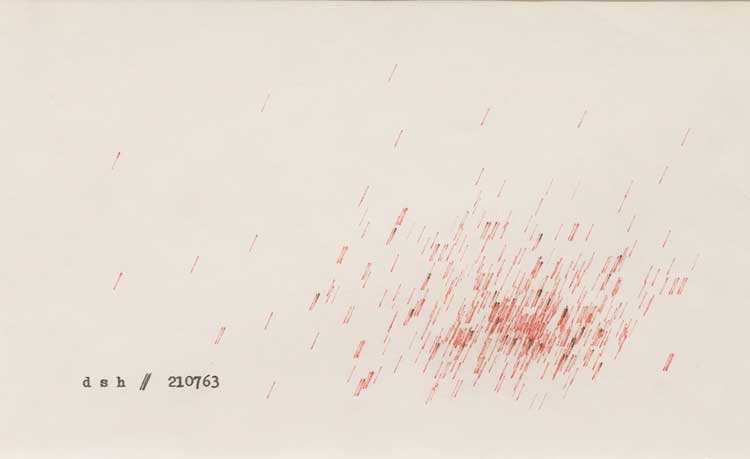

Dom Sylvester Houédard, Untitled, 1963. Typed page, 12.7 x 20.4 cm (5 x 8 in). Image courtesy of Lisson Gallery.

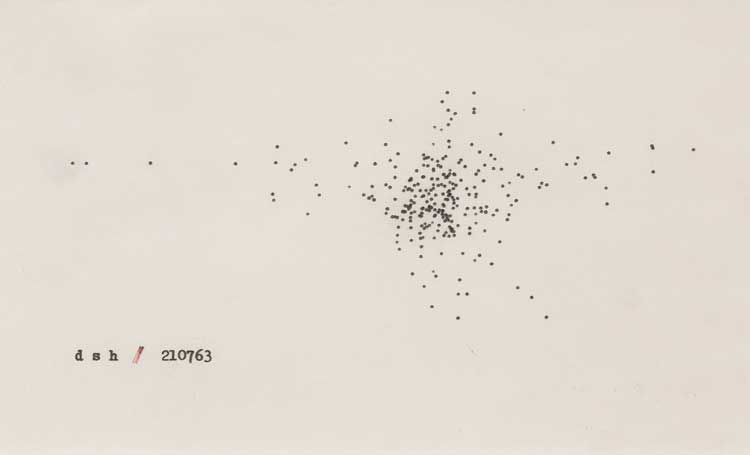

Two of the most exquisite works included are also the earliest; both are untitled and dated 21.6.1963. They communicate a minimalist purity of message, as if having emerged directly in one sitting from Houédard’s close engagement with the non-lexical properties of the typewriter he was using. One has been positioned like an Orthodox icon in an alcove to the left of a fireplace in the front room of the gallery. It looks like a cascade of thin red raindrops with a few tiny spots of soot. The other, dated the same day, shows a graphic constellation of small black dots, as if Houédard had gone wild on the punctuation point. Both are beautifully configured against a breadth of negative space.

Dom Sylvester Houédard, Untitled, 1963. Typed page, 12.7 x 20.4 cm (5 x 8 in). Image courtesy of Lisson Gallery.

In walking slowly around the exhibition, I am struck by the strength of the material by Houédard that has here been brought together. While at times in other exhibitions, his typestracts have seemed to me to veer towards the pictorial, the focus of this exhibition is on the relatively abstract.

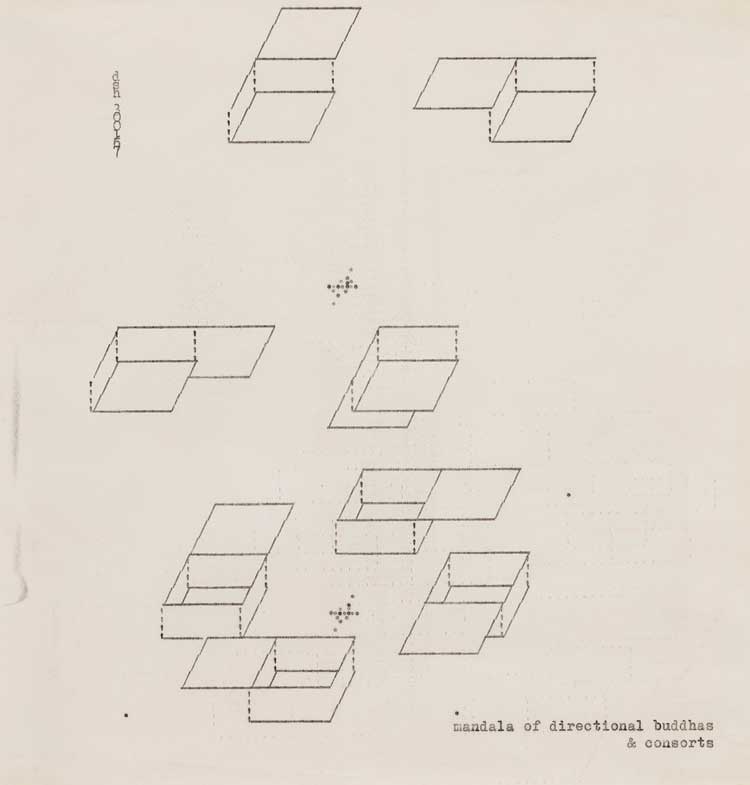

As we approach the 70s, the titles shown appear increasingly architectural and vectoral in their orientation, and yet, what is still being communicated is a depth of inner rather than outer space. Others appear to be hinting at a sexuality, expressed ambivalently; or playfully, such as we see in the work entitled Mandala of Directional Buddhas & Consorts (1967), which seems to me to be comprised of several rather fat and rather jolly little squares.

Dom Sylvester Houédard, mandala of directional buddhas & consorts, 1967. Typed page, 21.2 x 20.4 cm (8 3/8 x 8 in). Image courtesy of Lisson Gallery.

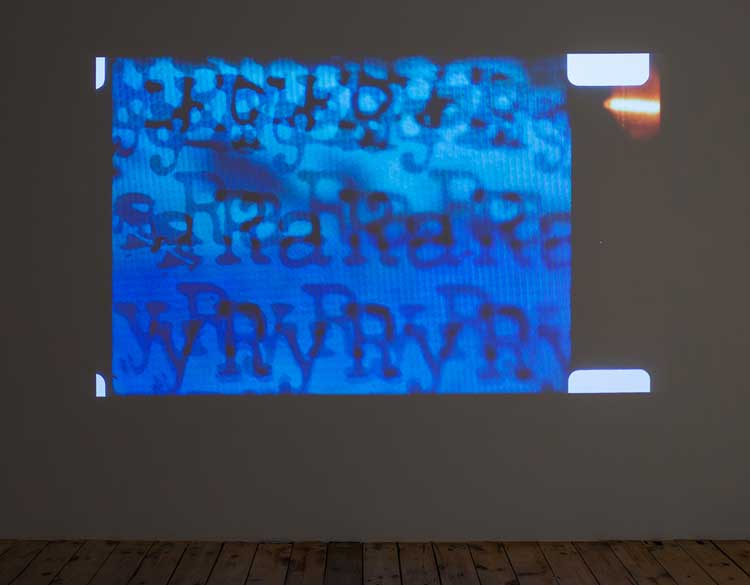

Exhibitions of Houédard have not been hard to find in commercial galleries over the last few years, with solo displays at Richard Saltoun in 2017 and the Lisson gallery in New York and London (2018 and 2020), as well as the Estorick Collection in 2025. During his lifetime he was a tireless connector of people, spreading word about concrete poetry and becoming one of its leading advocates in England. A little-known fact told to me by Tris Vonna-Michell – whom I met at the preview weekend for Condo (a collaborative exhibition when a number of London galleries host international and non-London galleries in their spaces) – is that dsh had invited Henri Chopin to show his first poem-film, called Pêche de Nuit [Night-Fishing], at Prinknash Abbey in 1963. Tris Vonna-Michell, nominated for the Turner Prize in 2014, meanwhile, was selected by Jan Mot gallery in Brussels to have an exhibition at TINA as part of Condo, but decided it would be a perfect opportunity to show an 1985 film that his father, EE Vonna-Michell, made with Chopin when both were living in Essex. The result is To Ray the Rays, a gorgeous exposition of a concrete poetry-film convergence, with letters being decomposed, erased and superimposed, and fading out and fading in, and changing colours and tones, then turning completely into visual shadows and colours, all of which I found hypnotising and totally compelling. Its audiovisual effects, meanwhile, add further to dimensions of movement implicitly transmitted by Houédard’s typestracts. This is believed to be its first screening in England.

Installation view at TINA, London, E.E. Vonna-Michell, in collaboration with Henri Chopin, To Ray the Rays,1985. 16mm film transferred to video, sound, colour, 7 min 55 sec. Image courtesy of the artist and Jan Mot, Brussels. Photo: Corey Bartle-Sanderson.

In 2022, Marc Matter wrote about Vonna-Michell and his work with Chopin for the Jan Mot Newspaper (No 130) in which he referred to Chopin as “a publisher of experimental poetry himself (OU review and edition)” as well as “a tireless connector of artists and scenes from the early 1960s on”. Matter added: “Together with Chopin, EE Vonna-Michell realised some forceful works of ‘expanded media’ combining language, noise, sound, moving images, visuals and space. Time-based and degradation processes, deconstruction or creative misemployment of media, as well as new forms of (graphic) scores were of high relevance in the collaborations with Chopin.”

Installation view at TINA, London, E.E. Vonna-Michell, in collaboration with Henri Chopin, To Ray the Rays,1985. 16mm film transferred to video, sound, colour, 7 min 55 sec. Image courtesy of the artist and Jan Mot, Brussels. Photo: Corey Bartle-Sanderson.

Tris Vonna-Michell has also described the process of sensitively restoring this work, after finding a box of materials after the death of his father in 2020, which included a reel-to-reel tape of To Ray the Rays (the second film that Chopin and his father had made together). In both films, EE Vonna-Michell, who was a printer, produced the visual compositions, with “the sound compositions by Chopin, using his voice, a microphone, tape recorder and speaker” as well his “characteristic technique of sonic assemblage [that] transcends the vocal utterances, by changing speeds, superimposing and manipulating, resulting in an intense feedback loop of vocal abstractions”. He also recognised in the editing process that his father had “alternatively spliced negative and positive film”. The net result is fantastic. If you like experimental film, concrete poetry and original effects that cannot be algorithmically reproduced, the film is on until Valentine’s Day.

Installation view at TINA, London, E.E. Vonna-Michell, in collaboration with Henri Chopin, To Ray the Rays,1985. 16mm film transferred to video, sound, colour, 7 min 55 sec. Image courtesy of the artist and Jan Mot, Brussels. Photo: Corey Bartle-Sanderson.