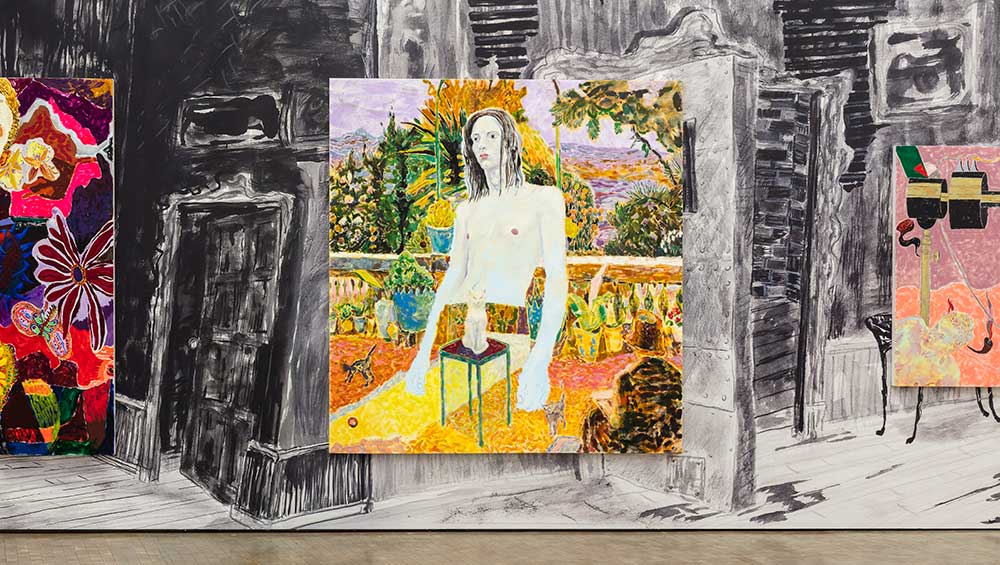

Richard Hawkins: Potentialities, installation view, Kunsthalle Wien 2025. Courtesy the artist; Galerie Buchholz, Cologne / Berlin / New York and Greene Naftali, New York. Photo: Markus Wörgötter.

Kunsthalle, Vienna

26 November 2025 – 6 April 2026

by TOM DENMAN

Western art history has always involved a bit of necromancy. We are fascinated by the work – or workings – of the dead, even the way it renders its maker undead, or so it is sometimes thought. Then there is the way artworks are haunted by other artworks – or by their own past selves, for that matter, with the vicissitudes of time and place altering their meaning and demeanour. Not to mention the exhumation of ancient remains (sometimes actual tombs), deemed to have kicked off a major strand of modernity (“rebirth”, as it is known, which could also signify a return from death). Add sexual awakening (or is it reawakening?), and all the shame, frustration, joy and ecstasy that comes with it, to the equation and you might get a phantasmic return of the repressed. An alike kind of carnal hauntology characterises the Dionysian world of Richard Hawkins. The American artist’s exhibition spanning three decades of about 100 paintings, collages, sculptures and videos – which explore the connubium of sexual energy and aesthetic recurrence – feels apt in the city accredited with the birth of psychoanalysis.

Richard Hawkins: Potentialities, installation view, Kunsthalle Wien 2025. Courtesy the artist; Galerie Buchholz, Cologne / Berlin / New York and Greene Naftali, New York. Photo: Markus Wörgötter.

Taking centre stage are Hawkins’s paintings from the past half decade or so. Big, bright and teenage-bedroomy, they are scattered with cut-and-pasted images of pretty young men, sometimes with ghoulish predators or horror-movie monsters lurking nearby, or accompanied by nice-looking fellows from the canons of art history – a Dutch cavalier, a hair-clothed John the Baptist. They have a deceptively slapdash feel, as if Hawkins had used a pinboard to arrange his compositions before painting them (several works have magazine clippings affixed to the canvas), while his patchily applied, candylike colours are an affront to the homophobia of the working-class Texas in which he grew up. As Hawkins hints in the first pair of works we see, Fruits in Mars Black Shadow (after Bonnard) and Fruits with Cadmium Yellow Teapot (after Bonnard) (both 2025), one of his technical sources for his dauby, chromatic play is the eponymous French post-impressionist. These accomplished still lifes – consider the interplay of tapestry-like patterning and illusionary depth, the suggestion of shadows and foreshortening, the way he makes his paintings look so easy when they are clearly not – act as a kind of aesthetic base for the show.

Right: Richard Hawkins, Left to His Own Devices, 2024. Acrylic on panel, 224 x 178 x 5 cm; Left: To Divide Him Vein by Vein, 2020, acrylic on panel, 178 x 223.5 x 5 cm. Installation view, Kunsthalle Wien 2025. Courtesy the artist; Galerie Buchholz, Cologne / Berlin / New York and Greene Naftali, New York. Photo: Markus Wörgötter.

The pair of after-Bonnards sets in motion a psychic process whereby faces come out of the paint. Hawkins posits an equivalence between the sensitivity to colour and pattern epitomised in Bonnard and expanding into abstractions reminiscent of Krasner and Kandinsky, his own homage – as irreverent as it is loving – and the erotic and deathly undercurrents of fetishising beauty. Dominating Left to His Own Devices (2024), against a background of spiny, tadpole-like forms in earthy yellow, fleshy pink, watery blue and black, is the actor Timothée Chalamet’s flowing-haired visage. Coming in from the right at 90 degrees is another young celebrity, in black scoop neck and cap, a similar type but blond (I am sure many viewers would recognise him; my knowledge of famous faces is poor), and to the left a prancing matador – an archetype of high-camp masculine beauty, testosterone and death, who reappears in Many a Whimpering Ghost (2019) and To Divide Him Vein by Vein (2020). Taking a turn for the ugly, contrasting with Chalamet is a hideous vampiric-looking rodent that might have just regurgitated another high-cheek-boned man’s head, set right in front of the monster, dripping blood.

-Richard-Hawkins,-Sombre-Soul-Unsleeping,-2020.jpg)

Richard Hawkins, Sombre Soul Unsleeping, 2020. Courtesy of the artist; Galerie Buchholz, Cologne / Berlin / New York; and Greene Naftali, New York.

Hawkins’s recent video works (2023-25), mostly no longer than five minutes in length and shown in rooms to the side of the gallery’s main space, animate the psychology of the paintings. It is almost as if we are watching the pictures come to life (“Stare at my paintings long enough and they will begin to do this, too,” Hawkins could be saying), with the artist’s incantatory use of AI getting the boys to wink, lick and spill blood, while the collaged elements shift and slide around to reveal others beneath them. The sacred is a recurring theme. Set within a screen shaped like a Roman-arched altarpiece or church window, the film version of Left to His Own Devices (2024) presents Chalamet wearing flowers in his hair and a string necklace (some kind of pseudo-indigenous ritual garb, perhaps) as he spews a phallic stream of gloopy water and a mysterious (or mystical) pink creature, part worm, part penis, pokes about his shoulders. In Manu Ríos, Unbeheaded (2025), the screen is split in two: in the lower portion are scenes from a film in which men check each other out in a shower, while above is digitally rendered, or altered, stained glass. In it, we see John the Baptist’s head on a salver, tassels (for self-flagellation) and the arrow-impaled torso of Saint Sebastian shimmying in and out of view, occasionally interrupted by a beatific vision of the eponymous Spanish movie star lifting his T-shirt.

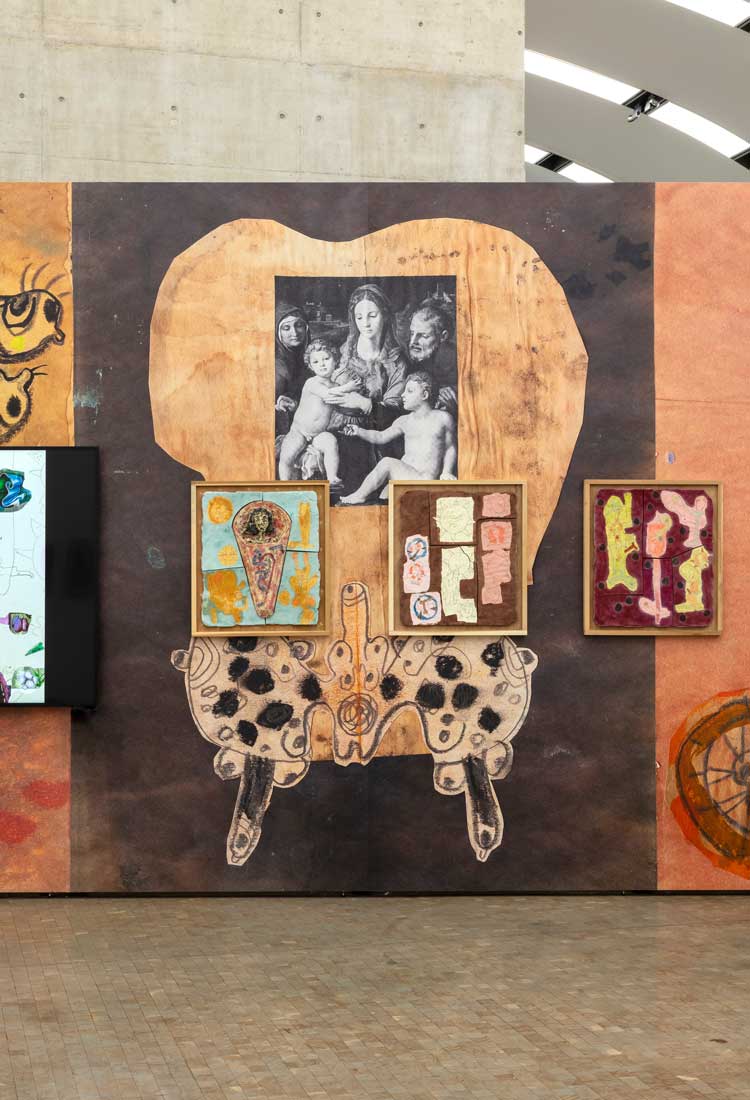

Richard Hawkins: Potentialities, installation view, Kunsthalle Wien 2025. Courtesy the artist; Galerie Buchholz, Cologne / Berlin / New York and Greene Naftali, New York. Photo: Markus Wörgötter.

A more analytical approach is offered in After Artaud (2012-2020), a series dedicated to the playwright and drama theorist who sought to invent a “theatre of cruelty” based on non-western ritual that tapped into our unconscious. It comprises framed ceramic reliefs of emblem-like images of mortality and sex: a coffined skeleton surrounded by phallic forms, a pair of splayed yellow legs against a pink background with three bullets hitting the crotch, the bloody wound bearing horns and an angry face. These are said to be based on Antonin Artaud’s notebooks from his travels in Mexico in 1936, inspired in no small part by the hallucinogens Artaud was taking. Amid these is Hawkins’s film Being and Its Fetuses (2023), featuring footage of Mexican religious festivals from Sergei Eisenstein’s ¡Que Viva México! (1932) and a drawing – from Artaud’s notebooks – of what could be an effigy of female fertility, over which Hawkins superimposes a sequence of Renaissance depictions of the Virgin Mary breastfeeding her child.

-Richard-Hawkins,-Ankoku-21-(Danae),-2012-Courtesy-of-the-artist_-Galerie-Buchholz,-Cologne_Berlin_New-York_-and-Greene-Naftali,-New-York_-photo_-Fredrik-Nilsen.jpg)

Richard Hawkins, Ankoku 21 (Danae), 2012. Courtesy of the artist; Galerie Buchholz, Cologne / Berlin / New York; and Greene Naftali, New York. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen.

On the opposite wall is Hawkins’s Ankoku (2012) series of framed collages consisting primarily of facsimile pages of the scrapbooks of the Japanese choreographer Tatsumi Hijikata, the inventor of butoh, known as the “dance of darkness” since it was intended to channel death and decay. The images, incidentally, mostly consist of clippings of erotic paintings and drawings of (oddly corpselike) women by iconic Austrian modernists such as Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele. Such dot-joining reminds me of the art historian Aby Warburg’s Bilderatlas Mnemosyne (1920s), a map of reproduced and collaged images from the history of art charting parallels and possible points of influence across time and place. For Warburg, aesthetic recurrences were a deeply psychoanalytic affair and not always conscious; as the art theorist Georges Didi-Huberman argues in his book on Warburg, originally published in French in 2002 – pertinently titled The Surviving Image: Phantoms of Time and Time of Phantoms – they could resemble a Freudian return of buried sexual urges.

Richard Hawkins: Potentialities, installation view, Kunsthalle Wien 2025. Courtesy the artist; Galerie Buchholz, Cologne / Berlin / New York and Greene Naftali, New York. Photo: Markus Wörgötter.

By bringing together early religious imagery, ritual performance, painting and AI, Hawkins taps into the psychosexual spookiness of creativity itself. In all this there seems also to be an ethics. The celebrity – which for Hawkins is mainly the male celebrity, but the situation might be analogous, although certainly not the same, for women – sacrifices himself as an object of worship, allowing his body to be fragmented, its components turned into relics like the head of John the Baptist. Whether good or bad, such brutal idolisation speaks to an impulse to glorify beauty – perhaps to seek some kind of transcendence in it – that is germane to the more cavernous reaches of the psyche, which the western canon has “tastefully” sublimated. What Hawkins’s art offers, it would seem, is a vessel for its weird and wild release.