-Emilija-Skarnulyte_Riparia-(2).jpg)

Emilija Škarnulytė, Riparia, 2023. Courtesy of the artist. Co-produced with Ferme-Asile and Taurus Foundation for Art and Science.

Tate St Ives, Cornwall

6 December 2025 – 12 April 2026

by VERONICA SIMPSON

I have Lithuanian artist Emilija Škarnulytė (b1987) to thank for being drawn deep into the world of the “hyperobject”. A term first popularised and disseminated in 2013 by the philosopher-poet Timothy Morton, I had only come across it very recently, and then in connection with global warming.1 A hyperobject can be anything of such scale and complexity that we humans struggle to understand it. As a 2021 interview with Morton in Wired proposed, it can also mean, “black holes, oil spills, all plastic ever manufactured, capitalism [and] tectonic plates”. In Škarnulytė’s film work, it might be river pollution, radioactive waste, the “dead zones” of the Baltic Sea, blindness and even time itself. That fear and awe we feel around something we experience as vast but unknowable is part of the magnetic force by which she pins you in place as you watch her films languorously unfurl. She is not the only artist to engage with the hyperobject. Philippe Parreno springs to mind, but where he uses the hyperobject of machine learning – specifically AI and data-harvesting technologies – to devise works that alienate, enchant and disturb, keeping you trapped within their technological spell, Škarnulytė is harnessing that feeling of magnitude and wonder to direct our attention towards things that matter in the real world.

-Emilija-Skarnulyte,-Tate-St-Ives,-2025.jpg)

Emilija Škarnulytė, Tate St Ives, 2025. Photo © Ansis Starks.

For her Tate St Ives solo show – her first major institutional presentation in the UK – she has placed her work in a unique spatial arrangement, directing our movements around two galleries in a choreography inspired by the architecture of Tate St Ives (its central, circular foyer, for example) and the ancient burial sites and standing stones she visited while preparing for this show. The dominant colour is a deep, submarine blue, an aquatic atmosphere fitting for an artist who learned to freedive (deep diving without the use of oxygen tanks) to execute her ideas.

In the main gallery, four large, white, curving screens form a circular, temple-like space, apparently inspired by Cornish Neolithic stone circles and the Metonic cycle (a 19-year lunar calendar period). Inside this space, in a near 360-degree presentation, we see Hypoxia (2023), a film that explores “dead zones” (areas where human activity or climate change have rendered life unsustainable) in the Baltic Sea, the camera panning over polluted seabeds, industrial waste and the ruins of a cold war submarine.

-Still-from-Aphotic-Zone-2022.jpg)

Emilija Škarnulytė, still from Aphotic Zone, 2022. Courtesy of the artist.

We also see Aphotic Zone (2022), “aphotic” being the name for parts of the ocean that light never reaches. Filmed off the coast of Costa Rica, it shows robots gathering samples in these zones, including a new species of coral that seems immune to pollution (which scientists hope might be used to patch up coral damage we have caused elsewhere). Also collaged into this moving-image medley is Sunken Cities (2021), in which the camera lingers over the remains of the Roman city of Baiae, which sank into the sea more than 1,000 years ago due to volcanic activity.

-Emilija-Skarnulyte,-Tate-St-Ives,-2025.jpg)

Emilija Škarnulytė, Riparia, 2023, Tate St Ives. Photo © Tate (Sonal Bakrania).

Finally, Riparia (2023) follows the Rhône between Switzerland and France, with two serpent-like figures gliding along the industrial waters (inspired by the Lithuanian archaeologist and anthropologist Marija Gimbutas’s research into Neolithic goddess figures). Between the breaks in these screens, we see printed works featuring bacteria, single celled organisms, that Škarnulytė has magnified and placed either in solitary cellular splendour around the room, or arranged into a wallpaper pattern across the interior wall (a pattern replicated on a handsome silk scarf, on sale at the Tate St Ives shop). This collaging of individual films works is intriguing and strangely seamless; one minute you are watching glittering, silvery fish moving vertically in the deep, the next you are up close to two snakeskin-costumed goddesses sliding through the water; then there is a detail shot of the remarkably humanoid robot-hands searching for samples along the seabed.

-Emilija-Skarnulyte,-Tate-St-Ives,-2025.jpg)

Emilija Škarnulytė, Riparia, 2023, Tate St Ives. Photo © Tate (Sonal Bakrania).

Projected along the entire 20-metre width of the far wall – visible between two of the curved screening walls – we see Škarnulytė performing one of her more spectacular aquatic feats for Aequalia (2023). She appears half-human, half-mermaid, in a pale, body-hugging costume with a muscular tail that flips vigorously as she navigates along the remarkable watery boundary of the Amazon where the milky, silt-infused waters of the Rio Solimões meet the Rio Negro’s dark, vegetation-strewn currents. The confluence of rivers produces flurries of resistance, the one warm stream breaking into foaming crests as it meets the cold eddies of the other. As she swims, we see pink river dolphins (also known as botos and sadly endangered) emerge and frolic around her, navigating by echolocation.

-Still-from-Aequalia-2023.jpg)

Emilija Škarnulytė, still from Æqualia 2023. Courtesy of the artist.

Another film collaged into this projected end-wall sequence is Rakhne (2023). Here, using computer imagery and AI-generated sound, Škarnulytė summons the angular geometries, snaking cables and blinking lights of a fictional underwater data centre – something she thought of as futuristic at the time of this work’s inception, but now discovers is already a reality. In an adapted version of her Sirenomelia (2017) and t ½ (2019) works, she plays a “siren archaeologist”, in a “post-extinction future”, showing us the remnants of human civilisation, from the Etruscan Necropolis of Cerveteri to the decommissioned Ignalina nuclear power plant in Lithuania (which stars in her film Burial, shown at last year’s Folkestone Triennial), and a cold war submarine base in Norway filmed for one of her first moving-image works. The Norwegian work necessitated her learning to freedive, as she couldn’t find anyone willing to play the role, which involved diving without breathing apparatus in temperatures of 4C.

Škarnulytė has called this end-wall compilation A Liquid Abyss: it features “human and non-human hybrids, threatened ecosystems and the ruins of lost civilisations both ancient and modern”. It’s all deeply affecting and hypnotising in the way she segues between the vast – aerial shots of her mermaid-tailed self, shimmying along the frothing borders of these two dramatically different bodies of water – and the very near, the fins and forms of dolphins nosing up to her (“I didn’t even know they were there,” she tells me later). I felt as if I could spend hours in there – though the whole sequence, she says, should take only 45 minutes to run through.

As carefully orchestrated as this collaging is, there has been an equally thoughtful placement of films, images and sculptures around the space that encourages you to inhabit the whole installation. At times, the films appear to move in sync – images and narratives dovetailing briefly across the room. This does much to make you feel fully present, all senses attuned to this immersive environment with its ambient, deep-water soundscape. Škarnulytė was aided in this scenography by Linas Lapinskas, a Lithuanian architect who works with her regularly to create these enveloping and engaging environments, which the Tate St Ives director, Anne Barlow, described as “portals”.

On the far side of these circular screens, we encounter a two-screen, 16mm film projection that Škarnulytė made last year, while on a month-long residency at St Ives’ Porthmeor Studios. Called Telstar, it drifts slowly between Neolithic and 20th-century relics: panning across the lichen-encrusted features of Cornish standing stones, including Mên-an-Tol and Lanyon Quoit, and then splicing these misty moorland landscapes with footage of Goonhilly Earth Station’s huge satellite dishes on the Lizard peninsula. In 1962, the first transatlantic television broadcast was sent from the US to Goonhilly via the Telstar I satellite – which this film also features, albeit in model form. Škarnulytė also films granular drawings she made of the standing stones, using locally sourced materials such as ground minerals, plankton-infused water, volcanic sediment, mustard pigments and sea salt. These organic, biological-looking, densely flecked drawings seem truly drawn from the same elements and atmosphere as the gnarled and lichen-spotted stones.

-Emilija-Skarnulyte,-Tate-St-Ives,-2025.jpg)

Emilija Škarnulytė, If Water Could Weep (Mermaid Tears), 2023–4 and Æqualia, 2023, Tate St Ives. Photo © Tate (Sonal Bakrania).

Closer to the entrance of this main gallery are some of Škarnulytė’s “Mermaid Tears”: elliptical blown-glass objects that undulate as if water has been made crystalline. They were also shown at Folkestone, and are inspired by the Lithuanian myth of the mermaid-like sea goddess Jūratė, who angered her father by falling in love with a human, whereupon he killed her lover and smashed up her palace, said to be made of amber. When pieces of amber wash up on the Lithuanian coast, they are colloquially known as Jūratė’s tears.

Emilija Škarnulytė, Aldona, 2013. Installation view, Tate St Ives, 2025. Photo: Veronica Simpson.

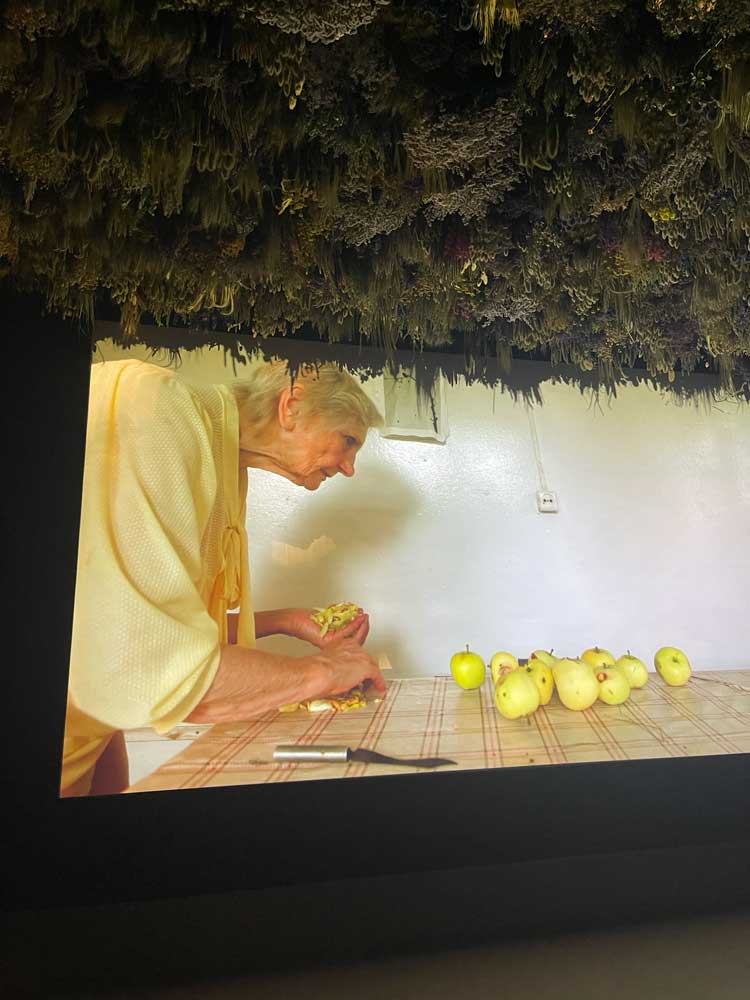

But it is blindness – a way of evoking the miracle of sight by capturing what it is like to live without it – that we first encounter in this Tate St Ives show, in the preceding gallery. This film, Aldona, is probably the one that has stayed with me the longest: one of Škarnulytė’s first film works (an evolution in her artistic practice that occurred while she was studying sculpture at Brera Academy in Milan), made in 2013. The subject is her grandmother (after whom the film is named), who became blind in 1986 – probably as a result of nerve poisoning caused by radioactive dust that swept across Lithuania following the Chornobyl nuclear power plant disaster. The film shows this elderly, but clearly very capable, woman as she goes about her daily life, in her kitchen and her garden, and also walking through Grūtas Park, a sculpture garden near her home that is filled with Soviet-era statues. As is now typical in Škarnulytė’s scenography, we have the lone figure almost swamped by the landscape – treading carefully, but without guide or stick, down the tree-lined entrance to the park; walking across its lush lawns – and then the detail shots: Aldona’s careworn hands feeling into and around huge bronze figures of Lenin and Stalin. “Tenderness” was the word that sprang to mind as I watched her fingers caressing the bulge and dip of Lenin’s nose, the crease and curve of his lip. At the preview, Škarnulytė said: “Aldona is also for me becoming like a blind prophet, touching these very cruel dictators but also guiding.”

There is a feel of something sacred and blessed about this film and this wise old woman, a feeling enhanced by the large canopy of dried herbs and grasses – some of which were gathered in that same part of Lithuania – that hangs over the screen, creating a fragrant canopy for anyone sitting on the bench to watch. Inhaling these scents – many herbs that Aldona and her community have used for centuries for healing as well as flavouring – enriches your engagement with the pastoral setting. And that lingering scent follows you around the rest of the show.

Unlike the feeling of paralysis and dread I felt after encountering Parreno’s digitally doctored, “hyperobject” universe at Haus der Kunst last year, Škarnulytė’s work left me feeling exhilarated. She shows us the power of the imagination to inhabit that vastness and bring our own agency to it. Having collaborated with Morton before, on books and exhibitions, it seems she aligns with his view (as he shared in the interview in the Wire), that while hyperobjects are “really big … they’re finite, so they can be defeated … We can help people by modelling how to step away … Although hyperobjects may insist that we understand, or at least live within, a world where humans are no longer as powerful as we once imagined, no longer the protagonists in the story of creation, they also offer something in return: intimacy.”

Reference

1. Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology After the End of the World by Timothy Morton, published by University of Minnesota Press, 2013.