Miquel Barceló, Artist, at Reflections. Picasso x Barceló exhibition at the Museo de Almería. Photo: Chema Artero © Museo Picasso Málaga © Museo de Almería, 2025.

Museo de Almería

16 December 2025 – 15 March 2026

by BRONAĊ FERRAN

In 2025, in the fine art world of art fairs and auctions, it was clear that the high-touch, earthbound domain of ceramics was finally coming into vogue. An early mover and shaker in this direction was Pablo Picasso, whose exhibition entitled Poteries in Paris in 1948-49 announced his embrace of this ancient tradition of making forms from fired and glazed clay.

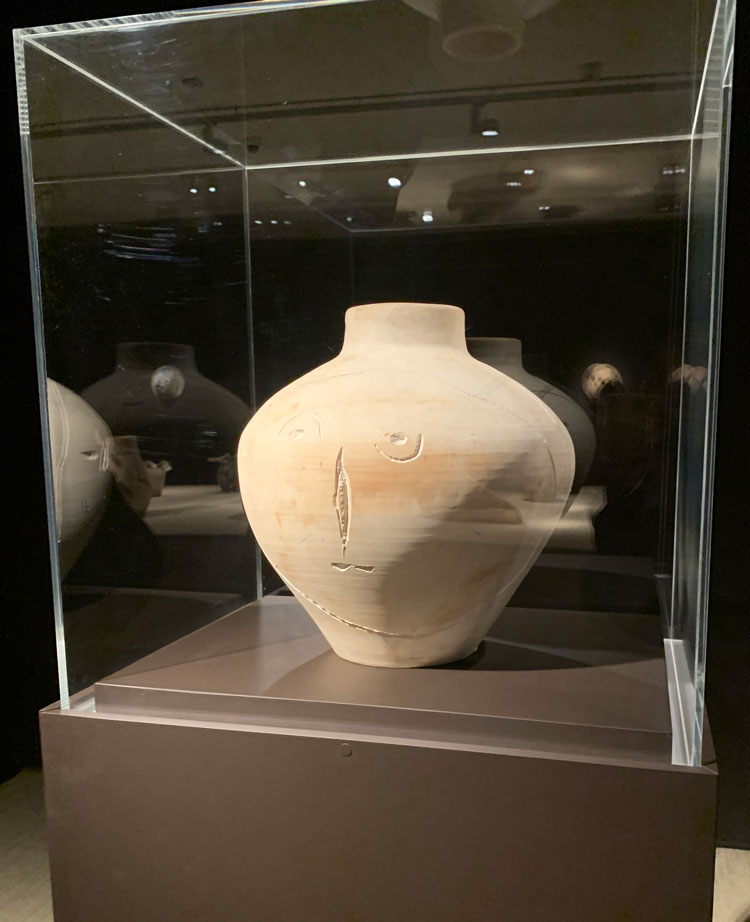

The Madoura pottery in Vallauris in the south of France became his laboratory of experimentation. He set out to transform the craft into a new artform. In the next two decades he created thousands of works involving glazing and painting on standardised pots, plates, vases and discarded fragments found within the studio. For Picasso, the three-dimensional possibilities of working in this medium were liberating in terms of its capacity for integrating aspects of painting and sculpture. He also sometimes painted on discarded and found fragments in the pottery. When he died in 1973, he left behind many ceramics, fired in the old wood kilns at Vallauris.

Miquel Barceló in the workshop. © Photo: Jean Marie del Moral.

I recently headed to Almería, on the Mediterranean coast in southern Andalucía, for the opening of an exceptionally lovely exhibition that highlights several lesser-known ceramic pieces by Picasso, including eight from the 1940s, in juxtaposition with contemporary pieces made by the Mallorcan-born Miquel Barcelo, one of Spain’s leading contemporary artists. Thirty-eight works by Picasso are on display. Some are in glass cases and accompanied by sketches, but others sit openly on the main table of the exhibition that runs almost the length of the gallery.

Alcazaba fortress in Almería. Photo: Bronac Ferran.

Barceló is showing 58 pieces in this exhibition, at least 25 of which were made in 2025, with the earliest dated 1996. Among the most visually effective are an untitled series from earlier this century, in which he includes lattice-like structures reminiscent of Moorish architectural features, such as can be seen in the stunning Alcazaba fortress in Almería.

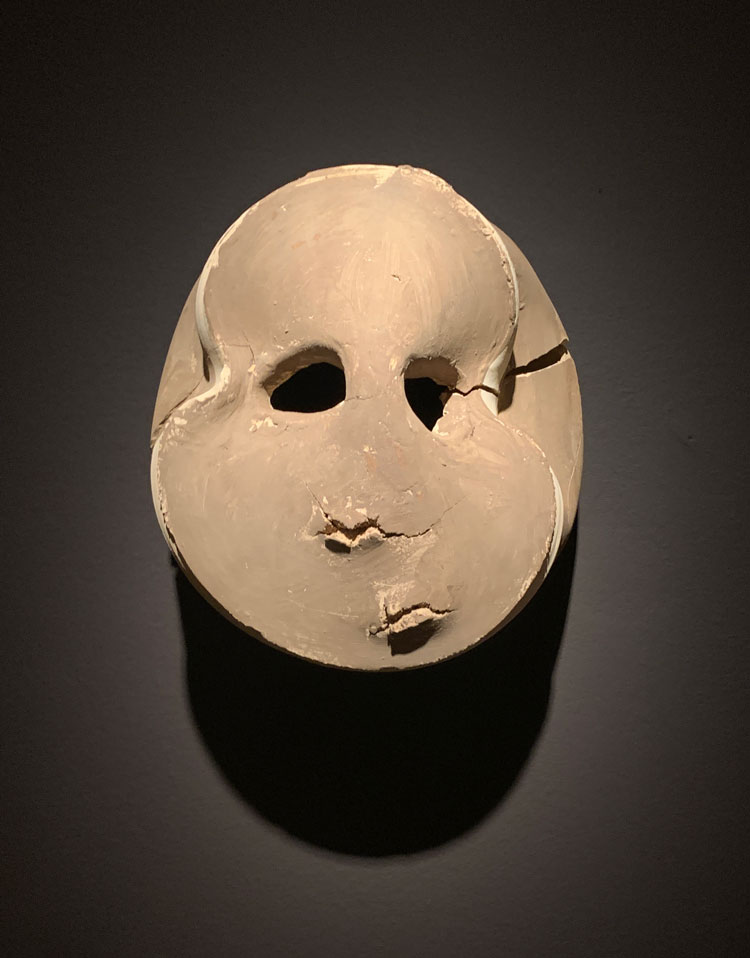

Added to this potent combination are 10 precious objects drawn from the Museo de Almería’s extraordinary archaeological collection, ranging from the neolithic era through the iron and copper ages, through to the Phoenician, the Roman and the middle ages. We see multiple resonances, differences and correspondences opened up curatorially between the surfaces and shapes and forms on display, in a beautifully lit exhibition that plays expressively with negative spaces and shadows. Among my favourite works are face masks (by Barceló) with gouged holes for eyes, that appear impossible to date at first glance.

Reflections. Picasso x Barceló, installation view, Museo de Almería, 16 December 2025 – 15 March 2026. Photo: Chema

Artero © Museo Picasso Málaga © Museo de Almería, 2025.

Co-curator of the exhibition, Miguel López-Remiro, artistic director of the Museo Picasso Málaga, refers to the lineup of ceramic pieces from various eras of human civilisation that draw us towards them with a poetic immediacy on entering the gallery as appearing to him like “an archaeology of the future”. He is touching here on a subliminal message flowing through this exhibition, which is that as the frictionlessness of today’s technological developments such as artificial intelligence grows ever more powerful, while drawing heavily on natural resources such as water at a time when the boundary conditions of human existence on this planet grow ever more unstable, the story of this era may be told in future through piecing together the fragments of today’s ceramics.

The project is the second instantiation of an initiative generated in 2024 by López-Ramiro and his team, in partnership with the Fundación Almine y Bernard Ruiz-Picasso, a foundation established by Picasso’s grandson, Bernard Ruiz-Picasso, and his wife, Almine. Under the theme of Reflections, they invite a contemporary artist to show their work alongside Picasso in the context of significant historical buildings and collections in Andalucía. It began with a “reflective dialogue” between Picasso and Jeff Koons, curated in the Palace of Charles V in the Alhambra in Granada in 2024, relating also to the collection. It was critically highly successful.

Reflections. Picasso x Barceló, installation view, Museo de Almería, 16 December 2025 – 15 March 2026. Photo: Bronac Ferran.

Barceló, with whom Picasso is linked in the current iteration, gained international recognition after his participation in the São Paulo Biennial in 1981 and in Documenta 7 in Kassel the following year. He was born in 1957, the year that Picasso visited an exhibition in Cannes of Spanish ceramics from the 13th century to the then present. Viewing works made in simplified, geometric forms and involving primitive depictions of animals from an earlier period, Picasso was heard to comment: “But is it possible that someone has done this before me?” These struck him as closely related to what he had begun to do at Vallauris. Indeed, Picasso’s ceramics are often characterised by a childlike iconic symbolism, from birds to bulls to the corrida (bullfight) and the sun that reveal how close his artistic vision in this later period was to his early childhood associations. Born in Málaga in 1881, he lived there for the first 10 years of his life. During the period of Franco’s rule in Spain, however, he refused to return. Yet his work remained closely engaged with a felt sense of relation to the Spanish landscape and other Spanish artists.

Pablo Picasso, Plate Decorated With a Goat's

Head. Vallauris and Cannes, June 5, 1952 and February 16, 1956. Empreinte originale in fired white clay, painted with slips and enamel, partially glazed. 31.5 x 51.5 x 5 cm. Fundación Almine y Bernard Ruiz-Picasso, Madrid © FABA. Photo: Marc Domage © Succession Pablo Picasso, VEGAP, Madrid, 2025.

Indeed, 1957 was also the year he was working intensively on his own, multiple, interpretative versions of Velázquez’s Las Meninas, producing sketches that have something in their resonance of the atmosphere of a collectivist assemblage found in the Museo de Almería exhibition. I am struck, too, by the sympathetic presence of a wall-based work by Barceló, the surface of which appears at first glance occluded and abstracted, yet which on closer looking becomes recognisably an image (or self-portrait) of his own face. Much like with Velázquez in Las Meninas, which seemed curiously modern in his reflexive inserting of himself – as the artist – towards the back of the picture, at various points in this exhibition I sense an intrusion of the so-called primitive into the modern, and into the so-called contemporary with the edges between these classifications, as well as between the form and texture of the work and the artist’s identity as a person, becoming blurred and subject to slippage. It is in this interstitial edginess as well as an ambivalent tension between object and relation that the aesthetic – and fine art – aspects of this exhibition come into fullest focus.

With such subtle reconfigurings, disfigurings and interlinkings, the exhibition seems to me to reveal the ongoing evolution of the concept of tradition itself. In several of the archaeological objects on display, we can see surface cracks and fractures that bear the patina of age as well as the process of later reassemblage. What is also curiously modern-contemporary, at least to my eyes, is how various fragments and the lines of breakage remain visible and become integral to the story and to the aesthetic effect.

Reflections. Picasso x Barceló, installation view, Museo de Almería, 16 December 2025 – 15 March 2026. Photo: Bronac Ferran.

Running like a throughline, meanwhile, is a sense of fragile continuity and levels of unpredictability. In an interview with Bernard Ruiz-Picasso published in the catalogue, Barceló speaks of how he is especially drawn to the time-based contingencies involved in the process of making ceramics: “What comes out of the kiln is a miracle that can’t be repeated.” He adds: “Ceramics are a multiplicity, a tool, a sort of delirium.”

This draws on his own deep immersion in processes of making pottery according to the Dogon earthenware tradition in Mali, in which he became absorbed when living there in the early 1990s. Thrown off course in terms of painting outdoors by the strength of the wind, he was shown by the women of the community how they created pottery, following an ancient tradition, sourcing the clay directly from the earth. He has applied related methods in many of his subsequent practice of ceramics, which has become an important strand of his overall oeuvre. The ceramic works he makes appear to still hold a terrestrial energy in their textures, unsettling conventions of closure, smoothness and curvature.

Reflections. Picasso x Barceló, installation view, Museo de Almería, 16 December 2025 – 15 March 2026. Photo: Chema

Artero © Museo Picasso Málaga © Museo de Almería, 2025.

Barceló was also involved performatively during the installation process the day before the preview opening, when he found there was a large glass vitrine left empty towards the back of the gallery. He asked if he might venture down into the basement storehouse of the museum, which contains its substantial collections. He brought back a selection of objects that he made into an assemblage with some of his own and Picasso’s smaller works. What this then turned into – to the surprise of the curatorial team – was a grotto, a traditional religious construct depicting the Epiphany, known as King’s Day in Spain, that remains a day of significant ritual and ceremonies of gift-giving to children. Giving Barceló the creative space to respond to the specificity of the context in which this exhibition is taking place, produced something contingent, magical and reflexive.

Indeed, the tale of the grotto becomes a sprite-like twist in the exhibition’s curatorial tail, reminding us of the long history of religious art in Spain, the importance of vernacular expression within this lineage as well as stories of Picasso using found objects in the Vallauris pottery. So, too, human origin stories, of Adam, and the Golem, first coming to life through the divine transformation of clay, find something of an affirmation through Barceló’s intervention that conjoins his own works – particularly the many small pieces he fired during 2025 – directly with works by Picasso and the museum’s collection in a time-based tableau.

Reflections. Picasso x Barceló, installation view, Museo de Almería, 16 December 2025 – 15 March 2026. Photo: Bronac Ferran.

Reinforcing the symbiosis between human existence and pottery as a synthesis of the four universal elements, this is also an exhibition that allows us to celebrate its basic value, as a physical, life-sustaining practice that modelled three-dimensional surfaces long before computer graphics. As part of articulating the concept of an archaeology of the future at the exhibition opening, López-Ramiro speculates that in 500 years, the names of Barceló or Picasso will no longer be remembered, but elements of their ceramic works may remain in circulation.

Showing us the wholeness in the fragments, and the fragments in the wholeness, while placing two of Spain’s greatest artists in a longer-term genealogy, this lovingly and luminously curated exhibition integrates past, present and future into a seamless wonder.

• Reflections. Picasso x Barceló will be at the Museo de Cádiz from 27 March – 28 June 2026. The exhibition is organised by the Museo Picasso Málaga in collaboration with the Fundación Almine y Bernard Ruiz-Picasso and the Andalucian ministry of culture and sport. The co-curators are: Miguel López-Ramiro, artistic director, Museo Picasso Málaga; Tania Fábrega, director, Museo de Almería; and Laura Esparragosa, director, Museo de Cádiz.