The Medium is the Message, installation view, The College of Psychic Studies, London, 2025. Left to right: Ithell Colquhoun (vitrine), Nicole Frobusch, Chantal Powell, Ithell Colquhoun. Photo: Dan Weill.

College of Psychic Studies, London

9 October 2025 – 31 January 2026

by ANNA McNAY

Before today, I associated Queensberry Place only with the learning of French at the Institut Français; little did I know that, all the while, across the road, another place of learning has all-too-aptly been hidden in plain sight – for the last 100 years, No 16 has been home to the College of Psychic Studies, where mediumship is the subject and object of study. To celebrate this centenary, the college’s curator and archivist, Jacqui McIntosh, has brought together more than 100 artworks and archival treasures, by more than 35 artists from the mid-19th century to the present day, to explore the long, rich and complex relationship between artistic practice and mediumship, in The Medium is the Message.

Anna Mary Howitt Watts, Untitled, c1856–72. Ink and gouache on paper. Collection of The College of Psychic Studies. Photo: Siyu Chen Lewis.

I chose to start on the fourth floor of the Kensington townhouse and work down through the 11 elegant rooms. This meant beginning in a space exploring themes of communication with spirit ancestors and the invisible forces of nature. One artist, whose work is on display here, is Anna Mary Howitt Watts, whose early experiences of spirit communication led her to reflect on nature’s divine origin and to feel a profound energetic connection with plants and flowers. This comes across especially in Untitled (c1856-72), which resembles a Chinese dragon with blooms as its tail, similar in shape to Anna Hackel’s Automatic Drawing (1934) hanging nearby. Cecilie Marková’s Flora and Faces (1960) also captures an anthropomorphic vision of plants. The face in Allen Moore o2o’s Automatic Drawing (2020), however, seems to appear from a tangle of thorns.

As well as automatic drawings, this first room also includes three notebooks containing automatic writings by William Stainton Moses, comprising various sizes of scratchy handwriting, with confessions, admonitions and even a verse in Old English.

Mimei Thompson, Ancestor (Transmission), 2023. Acrylic and gouache on paper. Courtesy the artist.

The most beautiful work in this room – if not the entire show – is Mimei Thompson’s Ancestor (Transmission) (2023), an acrylic and gouache on paper, made using the surrealist technique of decalcomania, to conjure ancestral presences from her family tree. Another contemporary piece is Courting of the Glistening Veil (2024) by Cara Macwilliam, who use automatism to create intricate and layered works in the face of an energy-limiting illness. This piece captures “that wild, intense build-up of the energy” relating to the opening of the veil before Samhain (Halloween), connecting this world and the other world.

The second room, titled “Between Worlds”, ranges across abstract and figurative pieces, such as the sweeping white arcs of Louise Janin’s music- and light-inspired Composition (date unknown) contrasting with the spectral white figures of Heinrich Nüsslein, who often worked in the dark or with his eyes closed, calling his paintings “picture writing”.

The spiritual doesn’t exclude the religious, and Arild Rosenkrantz’s Benediction (c1920-30) beautifully portrays the encounter between a man and an angel. Other artists feel themselves to be guided by angels, such as the artist Daniel. Daniel’s guiding presence is the Archangel Metatron, whose name he gives to his geometric work featuring a recurring Star of David, which, to him, represents the Merkaba – a spiritual vehicle thought to reside within each of us, offering a gateway to deeper connection, insight and spiritual understanding.

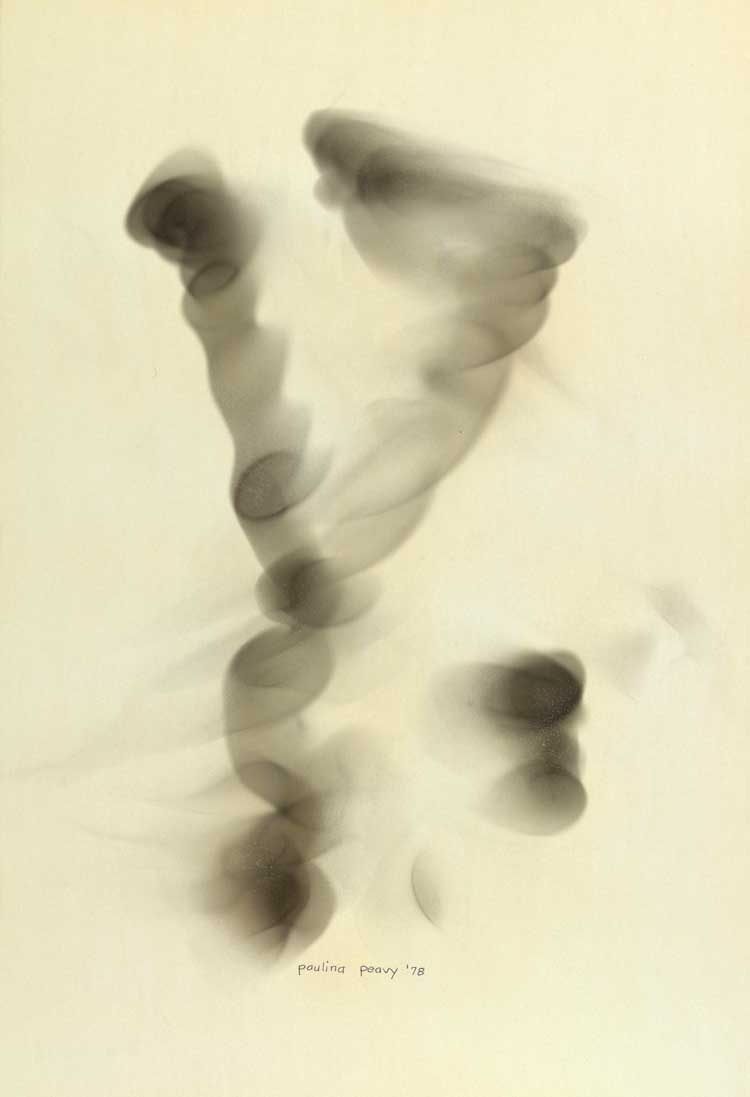

Paulina Peavy, Untitled, c1978. Smoke on paper. Paulina Peavy Estate, courtesy Andrew Edlin Gallery, New York. Photo: Siyu Chen Lewis.

Next is the first of five rooms, each dedicated to a single artist. This one is to the visionary artist, teacher, gallerist and medium Paulina Peavy (1901-99), who had a lifelong collaboration with the spiritual entity Lacamo. Her ink works often feature botanical forms interwoven with energetic and ectoplasmic shapes. God is Within (1953) is a particularly fine example, with the dark shape of a bird, its wings reaching out into networks of roots, with the shapes of ova and sperm behind (at least, that is what I see). Another great piece, Untitled (c1978), is a fumage work, where the sheet of paper has been passed over a candle, allowing the smoke to draw an image. Like decalcomania and automatism, this was a technique often used by the surrealist artists.

Sidney Manley, Untitled, c1965–70. Pastel on board. Collection of The College.

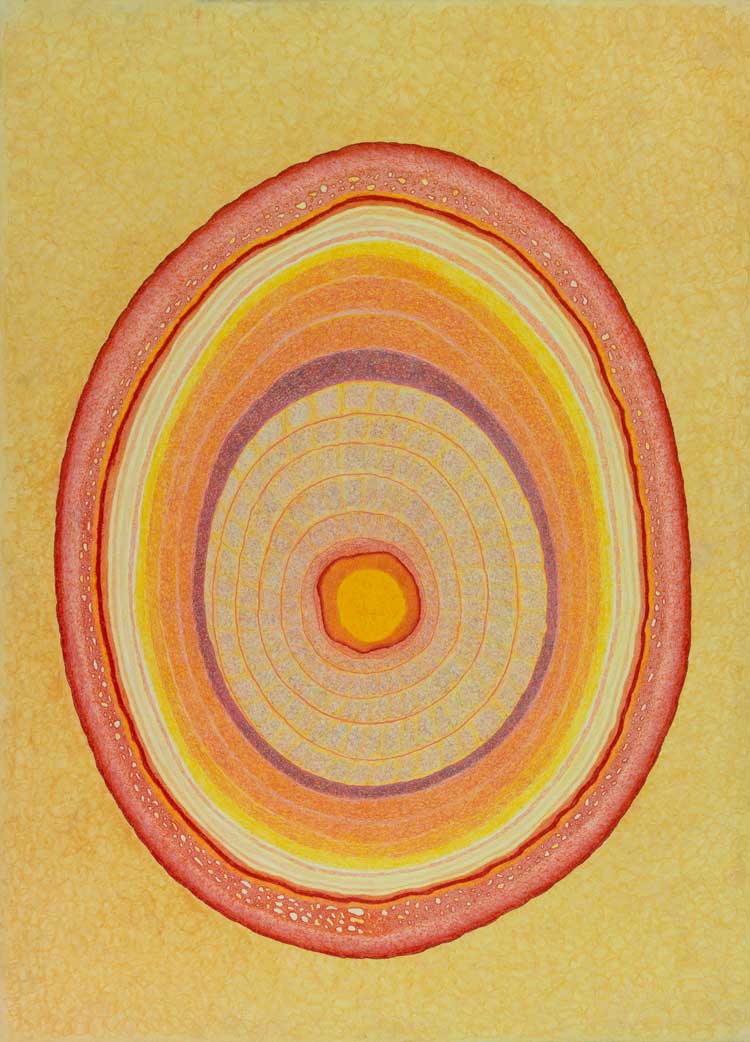

Alongside Peavy, the other spotlight rooms are dedicated to Sidney Manley (1900-70), Aleksandra Ionowa (1899-1980), Ethel Le Rossignol (1873-1970) and the aforementioned Howitt Watts (1824-84). Manley, one of the few men in the exhibition, is another of my favourites, producing simple, bold, colourful abstract botanical drawings, created slowly and with intense focus on the stamen, ovules and microcellular forms. Manley was a structural engineer and healer, who, despite initial scepticism towards spiritualism, began automatic writing and drawing in 1946 after visiting a medium. Of his process, he said: “The more successful I am in detaching my mind … the better will be the result.”

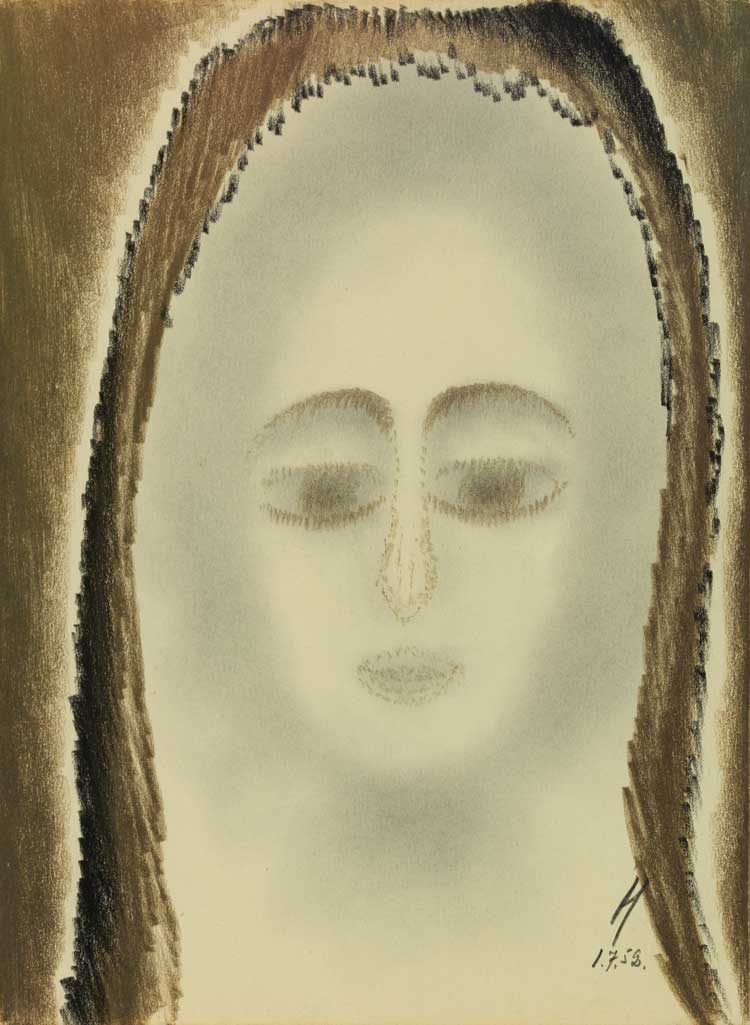

Aleksandra Ionowa, Untitled, 1959. Coloured pencil and graphite on paper. Collection of The College of Psychic Studies. Photo: Siyu Chen Lewis.

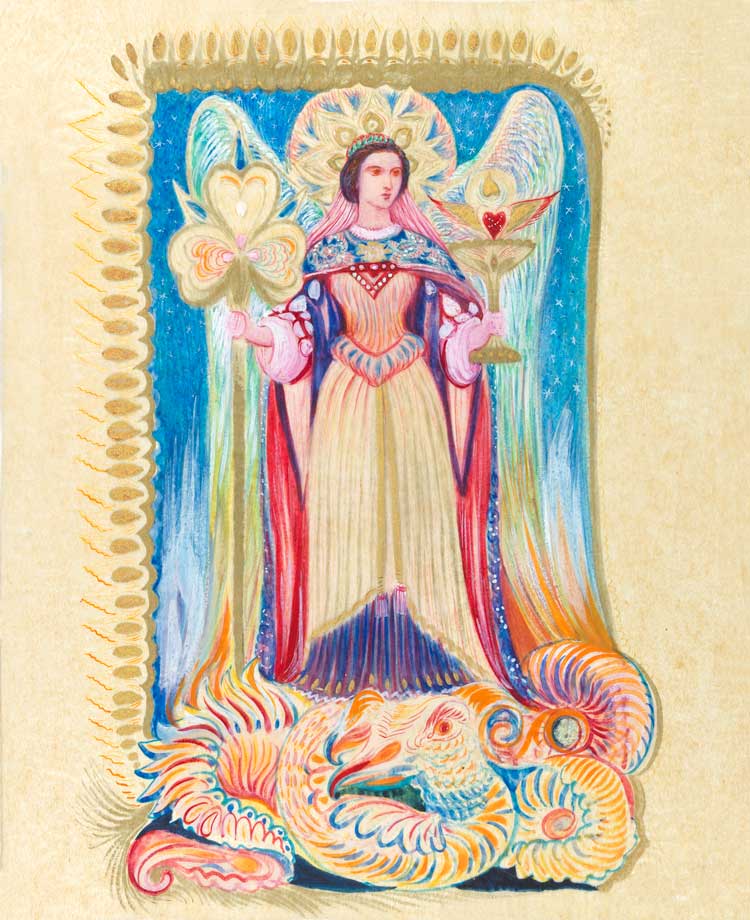

Ionowa’s approach was deeply rooted in theosophy and the writings of Madame Blavatsky. The figure of Christ appears frequently in her work, and she distinguishes between Jesus, as a historical figure, and Christ, as a divine principle present within each individual. Her pencil drawings are smoky and sparse. Little could be more diametrically opposed than the detailed rainbow- and gold-coloured patterns drawn by Le Rossignol, under the guidance of a spirit known as JPF. Each painting, which looks like a beautiful page of illuminated manuscript, is laden with symbolic meanings encoding teachings from higher masters.

Howitt Watts was a professional artist, illustrator and writer, as well as an early feminist. She was a close friend of the pre-Raphaelite artist Dante Gabriel Rosetti, and a drawing of her by him is on display, alongside drawings by both of them of the muse and artist Elizabeth Siddal. Other drawings by Howitt Watts share the pre-Raphaelite iconography of the beautiful maiden with long red hair surrounded by nature.

Sarah Sparkes, 101 GHost-stories:27. The Evidence, 2021. Gouache on khadi cotton rag. Collection of The College of Psychic Studies. Image courtesy the artist.

Two rooms are dedicated to some of the most influential mediums of the last three centuries, all closely associated with the college. Alongside archival material, there are contemporary homages by artists Dronma, Susan MacWilliam, Sarah Sparkes and Shannon Taggart. Sparkes, in particular, brings the personal into her work through the incorporation of a wallpaper pattern from her childhood home. Macwilliam uses photography and film-making, providing a documentary take, which is backed up by footage of original lectures.

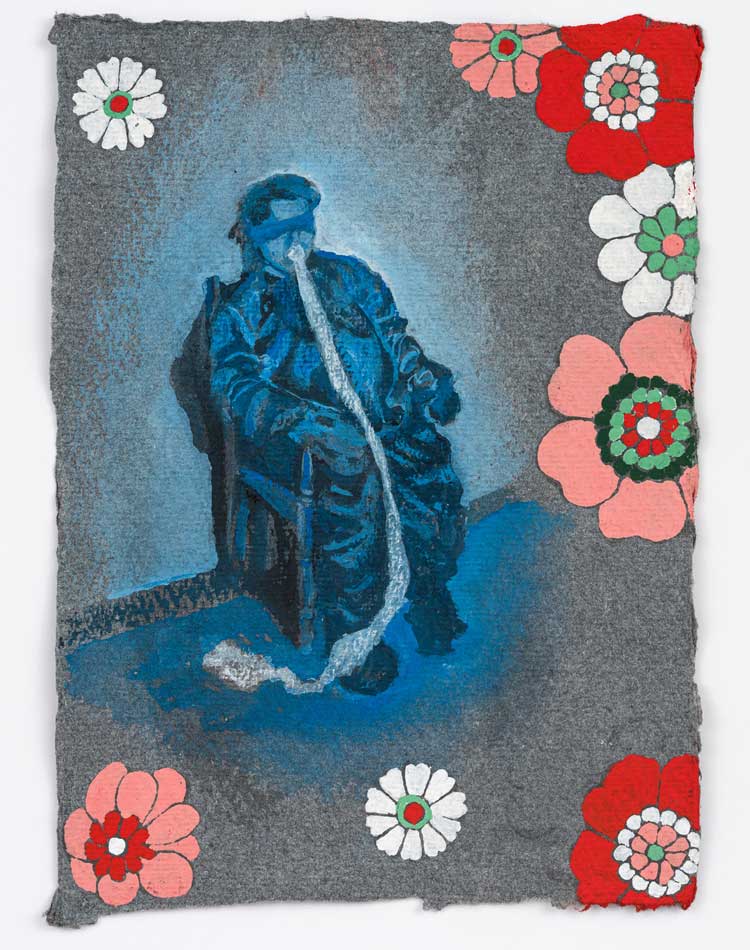

“The Earth is a Being” is my favourite room, featuring works by the British surrealist and occultist, Ithell Colquhoun, whose alchemical Diagrams of Love, Fire and Water (1941) is beautifully echoed in Chantal Powell’s hand-dyed calico embroidery, Natures Blent (2025), where the blue form, representing water, pierces the red form, representing fire, and is held by the green form, representing Viriditas, the life-giving vitality of nature. Another contemporary artist insightfully put into this room is Nicole Frobusch, who uses shapes reflecting roots and fallopian tubes, ovaries and the womb.

.jpg)

Ann Churchill, Large Blue Drawing, 1974–76. Ink on paper, 67.8 x 101.6 cm. Courtesy the artist. Photo: David Bebber.

The final selection of works by contemporary artists, down on the first floor, sits along the display of Le Rossignol. Ann Churchill’s Large Blue Drawing (1974-76) is every bit as laden with symbology as her predecessor’s work, and observation of it could become as meditative as its process of production. Mercury The Swift and Secret Messenger (2012) by Victoria Rance is a wearable sculpture for Mercury, referencing John Wilkins’s 1641 treatise on methods of transmitting information. It is her second work, The Well (2025), however, which is really the crowning glory of the exhibition, summing up its concern with supernatural communication, showing the layered realms of mind, body and spirit through the story of Mother Holle, a figure traditionally reached by falling down a well. The journey begins with the toad in the deepest, darkest corner, and rises up through layers of chalk and brick pebbles gathered from the River Thames, culminating in heavenly realms filled with angelic and goddess-like figures. Although I chose to take in the exhibition while descending, I nevertheless feel transported to some “other side” by the rich variety of works and laden symbology used by the artists in this show. While the meaning is often only to be intuited and found in that inarticulable space between words, there is certainly a tangible takeaway from this masterfully curated exhibition.