.jpg)

Something Else Entirely: The Illustration Art of Edward Gorey, installation view, Society of Illustrators, New York City, 4 October 2025 to 7 February 2026. Photo: Andres Otero.

The Society of Illustrators, New York City

4 October 2025 – 7 February 2026

by MICHAEL PATRICK HEARN

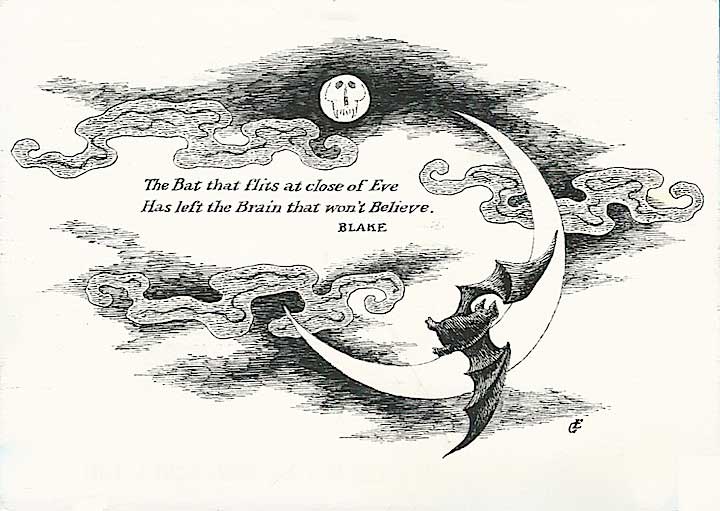

On 22 February 2025, Edward Gorey would have turned 100. He was a true original. No one else wrote like him, no one else drew like him. Gorey was always his own person. He did not care what anyone else thought of him. “What I’m doing and what other people think I’m doing are two totally different things,” he explained in an interview in the college magazine Florida Flambeau in 1984. “I see my work as a series of formal problems. What I do is sort of given to me from I-don’t-know-where. It sort of pops into my head.” Elegant, eccentric, erudite, eclectic, Gorey always enjoyed a good laugh. Although hardly a conventional cartoonist, he was first of all a comic writer and illustrator. He remains one of the few American artists whose name has entered the language: “Goreyesque” today describes any tongue-in-cheek grotesquery. He was the quintessential New York eccentric. Tall and slim at 6ft 2in, in a raccoon coat and white tennis shoes and sometimes his Harvard school scarf, with a full beard and cropped receding hair, he stood out in any crowd. Dressed in this uniform, he played the role of Gorey brilliantly. He may well have been the last true aesthete in the US. “I always felt the great crippling factor of my outlook or whatever was that I could never make it anything but aesthetic, if only because it makes me wonder if I ever feel anything at all. After all, the world is not a picture or a book or even a ballet performance, not really,” he confessed to his friend Tom Fitzharris on 15 August 1974, in the book From Ted to Tom, published last year. He always seemed out of place and out of time. And out of touch. “You never forget Gorey’s work once you have been exposed to it,” the comedian and talkshow host Dick Cavett declared on welcoming him on to his TV show in November 1977, “and you will certainly never come across anything like it elsewhere.” Film directors Tim Burton and Terry Gilliam and gothic writers Neil Gaiman and Lemony Snicket (AKA Daniel Handler) are among the many who have paid homage to the great Gorey. Handler sent him a couple of his works with a note, “saying how wild a fan I was of his books, and how I hoped he would forgive me for all I nicked from him”. Not surprisingly, Gorey never wrote back. Gorey was steampunk before there was such a thing. He was so 19th and early 20th century; and yet also was not. He is so firmly embedded in the popular consciousness that everything from Mad magazine to The Simpsons has paid homage to him. As he was perpetually uniquely himself, no critic has been able to convincingly nail him down. He went from cult figure to literary sensation until everyone knows him today. And he is the Sara Lee of illustration: nobody doesn’t like Gorey. Not that he would have cared. He did what he wanted to do, and the public be damned. If they liked what he did, that was fine. If they did not, that was fine too. He blithely went about his business. For years, he contentedly worked in relative obscurity. Few people could believe that this sweet, gentle soul could have been capable of such alarming works of madcap menace, mayhem and murder. Even the wallpaper seems hostile.

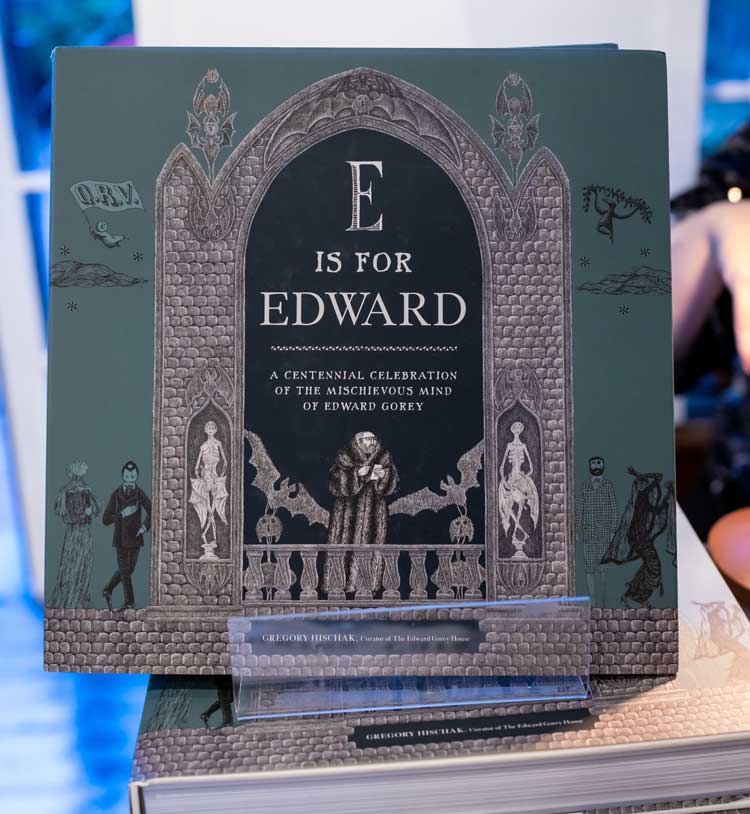

E Is for Edward: A Centennial Celebration of the Mischievous Mind of Edward Gorey by Gregory Hischak. Issued by the Edward Gorey Charitable Trust and produced in creative partnership with The Edward Gorey House. Photo: Andres Otero.

Gorey seemed to appear out of nowhere. Did he come out of his mother’s womb fully formed complete with that luxuriant beard? He would not have minded much if people thought he had. The recently published and sumptuous E Is for Edward by Gregory Hischak, curator of the Edward Gorey House, proves that the subject was himself once a child. It has snapshots of the tow-headed tot to prove it. (His hair darkened as he grew older.) Hischak’s tremendous tome is the sort of gorgeous oversized, overblown and lovingly researched coffee-table book usually reserved for the likes of Michelangelo and Matisse, all for an unpretentious artist who did his best work in glorious black and white. The massive volume weighs as much as a coffee table. Only the late Selma G Lanes’ The Art of Maurice Sendak (1980) comes anywhere near it. As in the Sendak book, some of Gorey’s pictures are so greatly enlarged that they betray the integrity of scale of the originals.

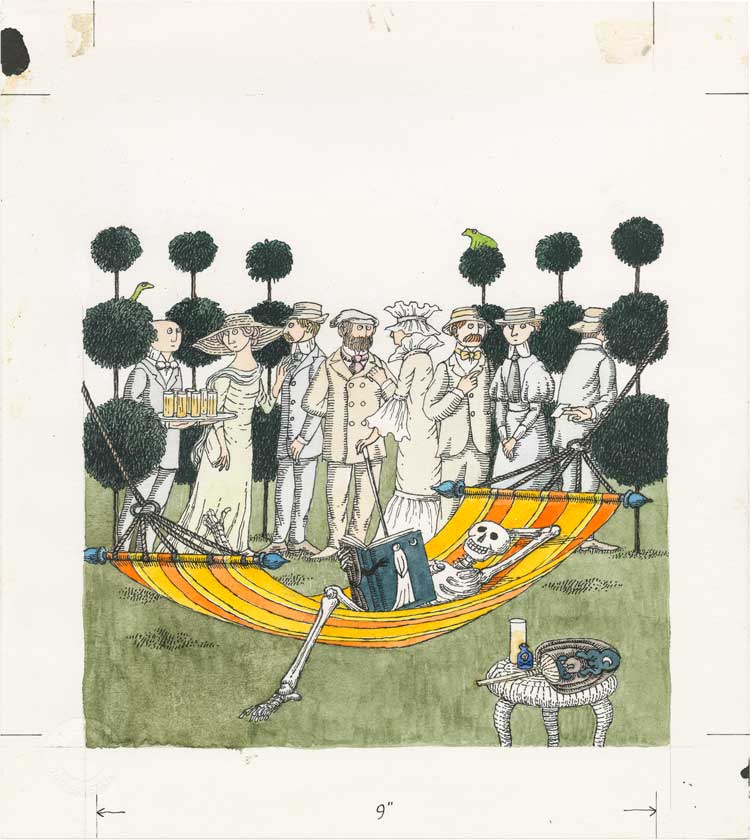

Why do so many boys and girls die such horrible deaths in his books? “Oh well,” he told the Los Angeles Times in 1998: “Children are the easiest targets.” He explained to Sally A Lodge in Publishers Weekly in 1982: “I tend to use children in my books, not symbolically really, but it’s much easier to do all this overdone pathos business with children.” Gorey knew: he had been one of those vulnerable kids. “Life is macabre and I try to show this,” he told Associated Press book editor Phil Thomas in 1984. “I’m not trying to make a statement, I’m trying to show how I think life is.” The same year, he told staff writer Richard Dyer in the Boston Globe Magazine: “Understand me: I think life is the pits, but I’ve been very fortunate. I don’t have any responsibilities to anyone except myself, and I have done pretty much what I wanted to do. Fortunately, I have never been into drink, drugs and depravity.” Gorey became famous for his deadpan approach to death. His personal philosophy did contain a certain tinge of fatalism. He said his “favorite genre” was the “sinister/cosy”. “I think there should be a little bit of uneasiness in everything,” he once argued, “because I do think we’re all really in a sense living on the edge. So much of life is inexplicable.” When it does happen, “you think, if that could happen, anything could happen.” It was his way of dealing with the inevitable absurdity of life. In his peculiar way, Gorey was supplying a modern equivalent of the medieval dance of death. Yet his skulls and bones are so benign they inspire amusement or bemusement rather than terror. His work is no more dangerous than José Guadalupe Posada’s satirical Mexican relief prints. Despite all the terrible things that occur in Gorey’s books, they never express any real despair. His attitude was that we are all heading to the grave, so why not have a giggle? Death can put up with anything but being laughed at. Despite the often-disquieting content, there is nothing depressing about Gorey’s art. He followed throughout his life the “great line” of the modern American dancer and choreographer Ted Shawn: “When in doubt, twirl.” One of Gorey’s most remarkable works is the existential The Willowdale Handcar (1962). Impulsive Edna, Harry and Sam suddenly seize a handcar from the train station and travel across the country to see “if anything was doing”. The trio are merely tourists who never engage in the strange events they encounter along the way. They travel aimlessly on to nowhere, like the young men in the popular US TV drama Route 66. Surely the journey, however pointless, is more important than the end.

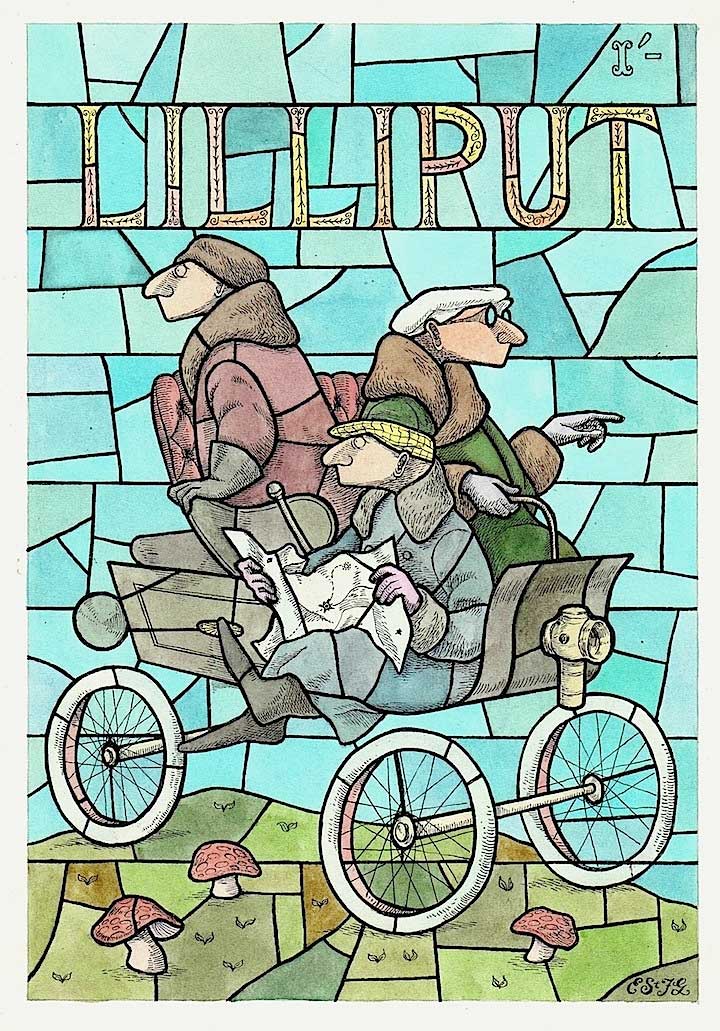

Lilliput Magazine Cover, unpublished circa 1952. Courtesy of The Edward Gorey Charitable Trust.

He told Terry Gross on her radio programme Fresh Air, on 2 April 1992: “I don’t think very much of my work has anything to do with my own life.” Once asked what he must have been like as a child, he answered simply, directly: “Small.” Edward St John Gorey (family and friends called him Ted) was born in Chicago on 22 February 1925, the only child of Irish American parents. His father was Catholic; his mother was Episcopalian. They tried to raise him as a Catholic, but he lost his faith at about seven when he got the measles. “I don’t believe in God in the Christian sense,” he told the novelist and poet Alexander Theroux in Esquire in 1974. “I’m not terribly religious.” Although most of his adult life was spent in Boston, New York and Cape Cod, he always considered himself part-midwestern. His parents greatly indulged him. He went so far as to admit that he was a bit of a spoiled brat. This precocious only child was drawing by a year and a half, “little trains that looked like sausages”. Both parents were voracious readers, particularly of mysteries; and Agatha Christie, he said, “is still my favorite author in all the world”. (He beautifully spoofed her work in the 1972 book The Awdrey-Gore Legacy, which critic John Hollander described in Commentary magazinein January 1973 as “a kind of do-it-yourself, early 20s detective-story kit, devoid of instructions for assembly, let alone plot, and consisting of images alone”.) Gorey taught himself to read at three and a half. He went through the Alice books, The Secret Garden and Winnie the Pooh. He took up Dracula at seven and it gave him the heebie-jeebies. Yet the European fairytales always disturbed him. The only Grimm he ever wanted to illustrate was Clever Elsie. He devoured the collected works of Victor Hugo by the age of eight, The Rover Boys at summer camp at nine. He once confessed: “I like to think of myself as a pale, pathetic, solitary child, but it wasn’t true.” No, he was “just your ordinary kid from the middle west”. He had a relatively happy childhood. He said he played kick-the-can like all the others. He lost the usual dog or cat when a boy, but he did not recall any unusual trauma at the death of relatives.

He was named after his father, a crime reporter with William Randolph Hearst’s Chicago Herald-Americanand other newspapers; his beautiful mother was a government clerk. The family moved around a lot in Chicago: by the age of 11, the boy had attended five different schools. That same year, 1936, his parents divorced when his father ran off with cabaret performer Corinna Mura, who later appeared in Casablanca strumming her guitar and singing La Marseillaise. Ted thought she was fun, but the relationship ended. His mother was going to marry a younger man, but he died. Until he was 27, Gorey saw little of his dad, but then his parents remarried.

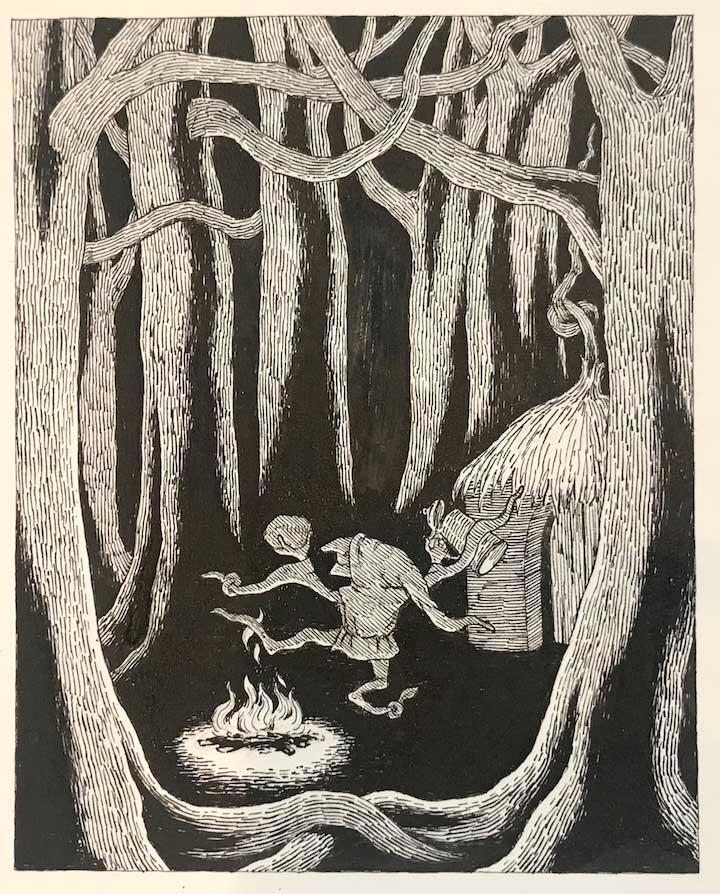

Tonight my cakes I bake... from Rumplestiltskin, published by Scholastic Books 1973. Courtesy of The Edward Gorey Charitable Trust.

Gorey was a good student and skipped first and fifth grades and graduated from the private progressive Francis W Parker school in 1942. He was reprimanded for skipping gym and not fully applying himself in his art class. The Parker Record published some of his earliest work; and he exhibited in the annual art show. His classmates included the abstract painter Joan Mitchell and the illustrator Connie Joerns, a lifelong friend. “In my opinion the value of a work of art is, to a great extent, independent of the artist,” Gorey declared in his senior essay on Vincent and Theo van Gogh. “The only relevant factor on which the merit of a picture may depend is the personality of the one judging the picture. However, some conclusions as to the underlying qualities of the picture may be drawn by an observation of the artist’s life.” He was largely self-taught except for Saturday classes at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. After only a semester, he was drafted into the army in 1943. He never saw combat. Instead, he was stationed for two years typing away as company clerk at Dugway Proving Ground in Utah, a testing base for poison gas and mortars. He filled in his free time writing unproduceable plays.

On being honourably discharged in 1946, he went to Harvard on the GI Bill (which provided veterans with funds for education), and roomed with the poet Frank O’Hara. They were like the school’s answer to London’s Bright Young Things, drinking cocktails to Marlene Dietrich records, until they drifted apart after two years. A diffident, indifferent student, Gorey read Ivy Compton-Burnett, Ronald Firbank (“the greatest influence on me”) and Evelyn Waugh among others. Jane Austen became one of his favourites because he found it “enthralling to read the miniature details about how people live their uneventful lives”. Gorey, too, was expert at making something out of nothing: for example, The Water Flowers (1982) is all about an abundance of lumpy white sauce that not one of the snowbound Christmas revellers wants to eat. Who else could make the banal so funny? As usual, the pictures are superb. He told journalists David Ansen and Phyllis Malamud in Newsweek in 1977: “Jane Austen knew more about anything than anybody else who ever lived – how awful it really is underneath.” (Had he had the choice, he would have written like Austen and drawn like Rembrandt.) He was also a big fan of Anthony Trollope and of Lady Murasaki, famous for The Tale of Genji. He eventually named one of his beloved cats after the Japanese writer, others after characters in her novel. He briefly worked for Adlai Stevenson in 1952, but the experience so upset him that it was his only public activism. He said politics bored him.

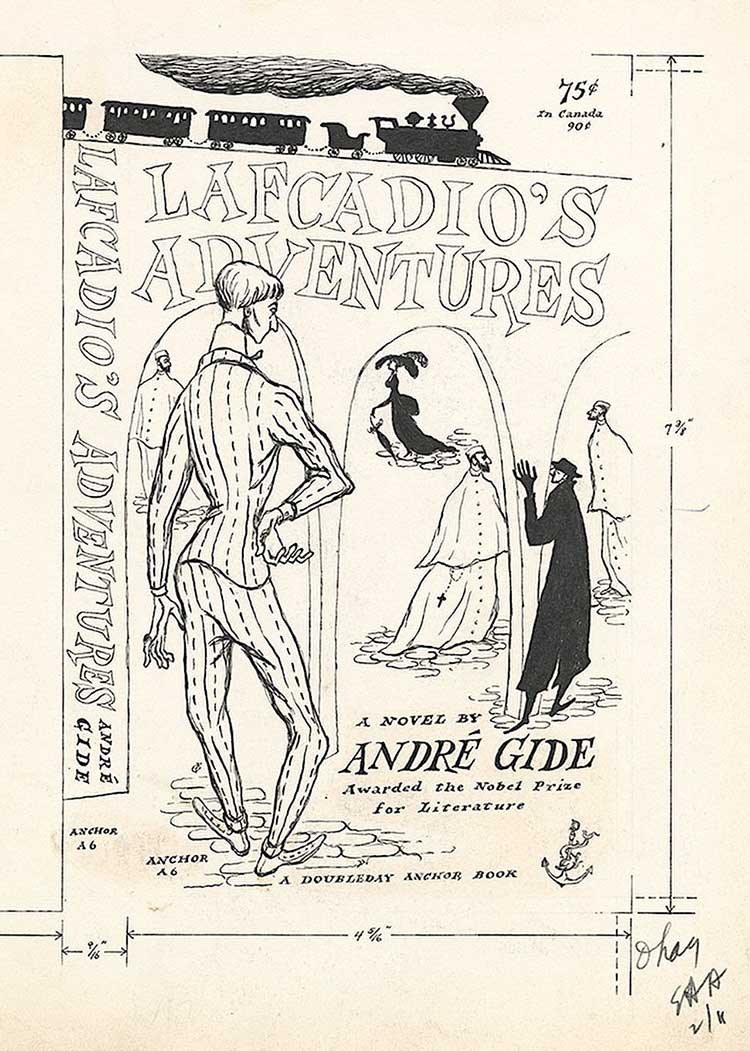

Cover art for Lafcadio's Adventures by Andre Gide, 1953. Pen and ink on board. From the collection of the Edward Gorey Charitable Trust.

He submitted poems and stories to the undergraduate literary magazine Signature, drew covers for the Harvard Advocate, and earned a degree in French literature in 1950. He had already gone through most of the 19th-century English classics (“I feel most at home in that genre”); and “I figured nothing in the curriculum would advance my career, so why not take French?” He thought the department was lousy. Nevertheless, the surrealists in particular inspired him. “I sit reading André Breton and think, ‘Yes, yes, you’re so right,’” Gorey gushed to writer Jane Merrill Filstrup in the Lion and the Unicorn in 1978. “What appeals to me most is an idea expressed by [Paul] Éluard. He has a line about there being another world, but it’s in this one. And Raymond Queneau said the world is not what it seems – but it isn’t anything else, either. These two ideas are the bedrock of my approach. If a book is only what it seems to be about, then somehow the author has failed.” Although he did not share the French painter’s sexual preferences, Gorey also adored Balthus (whose drawings he collected) through their mutual interest in cats. He also liked the Englishmen Francis Bacon and Edward Bawden.

Although he adored Austen, Gorey called Henry James his bête noire. “Those endless sentences,” he complained. “I always pick up Henry James and I think: ‘Oooh! This is wonderful!’ And then I will hear a little sound. And it’s the plug being pulled … And the whole thing is going down the drain like the bathwater.” Only The Turn of the Screw and possibly The Aspern Papers were bearable. Gorey’s ornate tongue-in-cheek verbiage may be seen, in part, as revenge on Jamesian verbiage. Thomas Mann was no better: “I dutifully read The Magic Mountain and felt as if I had TB for a year afterward.” The German was “exhaustive without being convincing”. He also loathed Henrik Ibsen.

Perhaps the artistic personality Gorey most resembled was the bard of nonsense, Edward Lear. He could have stepped out of one of the Englishman’s children’s books. They looked remarkably alike. Ted and Ed each bore a glorious beard and both adored cats. (Neither had a known longtime companion.) Gorey’s distinctive felines owe much to Lear’s sketches of his beloved affectionate Foss.

Gorey and Lear,

Each prodigiously queer,

Mastered both drawing and word.

No matter how serious,

The theme turned delirious

And always came out quite absurd.

They were both largely self-taught artists. Their whimsical wordplay was pure genius. Like Lear, Gorey was in the habit of using perfectly good words in unexpected ways. No one else has ever come up with more enigmatic, even banal but still enticing titles: The Fatal Lozenge (1960), The Curious Sofa (1961), The Willowdale Handcar (1962), The Inanimate Tragedy (1966), The Blue Aspic (1968), The Iron Tonic (1969), The Epiplectic Bicycle (1969), The Sopping Thursday (1970), The Deranged Cousins (1971). The Abandoned Sock (1973), The Disrespectful Summons (1973), The Lavender Leotard (1973), The Glorious Nosebleed (1975), The Loathsome Couple (1977), The Dwindling Party (1982), The Eclectic Abecedarium (1983). The Prune People I and II (1983 and 1985), The Improvable Landscape (1986), The Dripping Faucet (1989), The Fraught Settee (1990), The Betrayed Confidence (1992), The Pointless Book (1993), The Unknown Vegetable (1995), The Deadly Blotter (1997). One can only guess at their contents. That only makes his work all the more alluring. Like his esteemed English predecessor, Gorey had a remarkable gift for limericks and Abecedarian. “I like alphabet books, you know,” he admitted in a conversation with Matthew Joseph Bruccoli in 1977; “they’re already ready-made, shaped, too.”

Gorey and Lear were equally dexterous at sly nimble parody. Many observers mistook Gorey for an Englishman. He preferred to use the British spellings of words that added to the offbeat nature of his picture books. Hollander quibbled that Gorey dared rhyme “sherry” and “fairy”, “daring” and “herring”. He blamed it on Gorey’s “midwestern American ear”. One thing the two nonsensists disagreed on was travel: Gorey had no interest in exploring foreign lands as Lear had. The avid Anglophile left the US only once, in 1975, on an Atlantic voyage to Scotland with Tom Fitzharris because he was a big fan of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s 1946 movie I Know Where I’m Going! He went solely for the scenery. He once seriously considered visiting London, but then backed down because he was afraid he might never come back. It might not have turned out to be the monarchy of his imagination. The novelist Alison Lurie said Gorey “didn’t want to see the England of supermarkets and shopping carts – the Americanized, commercialized England that developed after World War II.” He lacked any wanderlust.

Unlike Lear, Gorey was never a baby magnet: he did not particularly like boys and girls. “I don’t have any relationship to children,” he admitted in People in 1978. “A lot of my books I’ve intended for children primarily, but nobody would ever publish them as children’s books. Children are pathetic and quite frequently not terribly likable.” He had no real interest in having anything do with them beyond the printed page. Gorey did illustrate lesser-known nonsense songs by Lear in the same format as his now famous picture albums, The Jumblies (1969) and The Dong with the Luminous Nose (1969), in which he fully captured the spirit of their original creator. Gorey wanted to do the pair of Lear books and was always proud of his work on those two largely forgotten books. He pays loving tribute to Hokusai’s The Great Wave off Kanagawa in the turbulent shore of The Dong with the Luminous Nose. He dedicated The Jumblies to Lear’s Foss, and The Dong with a Luminous Nose to his own cats. It is a shame he never illustrated The Owl and the Pussy Cat.

Gorey developed several important enduring friendships in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Poet John Ciardi was his creative writing teacher at Harvard; and the two later collaborated on several collections of light verse for children. This was also where Gorey met the future Pulitzer Prize-winning Lurie, then a Radcliffe student, at the appropriately named Mandrake Bookshop in 1949. The store gave him his first exhibition. “He looked like a pale lanky engineering student,” Lurie recalled, “unstylishly dressed and unremarkable except for his height. He had a crewcut and no facial hair; he wore T-shirts and jeans and sneakers, and when it was cold, a black turtleneck sweater.” Gorey was already wearing rings on his fingers and his signature old coats. The young man was “immensely intelligent, perceptive, amusing, inventive, skeptical, and a scarily gifted artist”, someone who quickly “saw through anyone who was phony, or pretentious, or out for personal gain”. They amused themselves by making rubbings of neighbourhood tombstones and formed, along with Ciardi, O’Hara, Richard Wilbur, Donald Hall, John Ashbery, Kenneth Koch and other local talent, the Poets’ Theatre of Cambridge. While Lurie worked primarily on makeup and costumes, Gorey designed sets and drew the programmes and posters and wrote short plays such as Amabel or the Partition of Poland, Undine, and The Teddy-Bear, A Sinister Play as “Edmund Godelpus”, “Eldritch Gorm” and “Egmont Glebe” among other intriguing pseudonyms. She recalled in a talk at the Edward Gorey House in 2008 that he was “one of the sanest and calmest people in the whole organization”.

Lurie insisted that she and Gorey were “best friends” as they struggled during those early lean postgraduate Cambridge days. With many tastes in common, the two went to museums and movies together or out for coffee. A bookstore hired him while she toiled in the Rare Book Room of the Boston Public Library. She had access to a locked stack of outdated erotica that she made available to Gorey, but he had no taste for pornography. “It’s so boring!” he declared. And rather silly. (Friends assumed he based Alice in his “pornographic” satire The Curious Sofa of 1961 on Alison Lurie: they had the same hairstyle, but she denied she had any of the experiences described in the book.) Lurie was married with a child now and once mentioned her frustration with her “beastly baby”. This offhand remark suggested, as he wrote to her in September 1953, “a sort of depraved cautionary tale with no moral at all”. Thus was bornThe Beastly Baby, the first of Gorey’s deliciously peculiar little picture albums that he wrote and illustrated. “As it happened, as it always seems to, which is sometimes boring and sometimes not,” he recounted to her, “I got into a kind of flap over the weekend, and wrote an illustrated a book which I am dedicating to aforementioned infant … It is apparently very odd indeed.” Others thought it was so unpleasant a story about such an unpleasant creature and unsuitable for children that Gorey had to publish it himself under the anagram “Ogdred Weary” in 1962. “My boys love it,” Lurie assured him when it finally did come out. “So, I want you to know that there is one family in the world in which your books are as much a beloved part of childhood as Beatrix Potter.” He was likely as much alarmed as flattered by her kind encomium. Lurie later insisted that her lads turned out just fine.

Gorey dedicated another of his early masterworks, The Doubtful Guest (1957), to her married name, Alison Bishop. When her son was not yet two, she told Gorey how “having a young child around all the time was like having a house guest who never said anything and never left”. Gorey’s strange undefined furry being, clad in school scarf and high-top sneakers (like the artist himself), whom he christened the Doubtful Guest, suddenly shows up in a middle-class household and does all sorts of annoying things like a petulant child. It stays for 17 years with “no intention of going away”. Lurie’s own Doubtful Guest finally left home at 18. The book serves as a warning to anyone who might be considering having a baby. The Doubtful Guest (initially the vapid “The Visit”) was originally marketed to the juvenile trade. “A lot of my books I intended as much for children as for adults,” he told Lodge, “but no one would ever publish them as children’s books.” Intrigued by the curious pictures, they read them anyway. “I would have loved them as a child,” Gorey insisted and said he aimed much of his work at “reasonably small children”. Girls and boys tend to adore nonsense and have taken Gorey to their hearts. They know that one does not have to entirely understand a story to enjoy it. Adults worry too much about structure and logic and fear the books that might scare the pants off their kiddies. The little ones rarely do. Gorey admitted in the Globe in 1984: “If you are writing something as brief as my books, it almost has to be about the lives of children. Also, children are the most vulnerable of creatures.” When asked on CBS Sunday Morning in April 1997 to whom his work appealed, he replied: “Sometimes they are about three years old and sometimes about 90 and sometimes, they are sort of demented and sometimes … I think, ‘Gee, you don’t look as if you like my books.’”

Gorey was just getting by when he departed for New York City in 1953 after snagging a job as an art director at Doubleday to design covers and typography for more than 60 Anchor paperbacks. He did not care for the city much at first. “I feel like a captive balloon, motionless between sky and earth,” he wrote to Lurie that September. “I want birds to bring me messages.” Book production was highly standardised at the time. Doubleday used only three typefaces and certain specific dimensions for its books. His professional career in illustration began at a time when publishers still held such little regard for the artwork that editors and designers thought nothing of returning it marked up with printer’s comments and dirty thumbprints and stained with Scotch tape, mucilage, rubber cement or some other acidic glue. Some publishers retained the pictures while staff occasionally helped themselves to drawings they fancied. (Gorey, too, succumbed when he found Doubleday’s hoard of forgotten art in its files: he filched three of George Herriman’s pictures for Don Marquis’s Archy and Mehitabel of 1933.) Gorey commenced his extraordinary career with, appropriately, The Unstrung Harp (1953), a diverting tale of what it means to be a struggling writer, here Clavius Frederick Earbrass of the stately home Hobbies Odd, near the town of Collapsed Pudding, in County Mortshire, begun when Gorey was still an undergraduate at Harvard. “It was all about writing,” he told the Boston Globe in 1984, “which I knew nothing about.” Yet every writer knows those literary parties where “the talk deals with disappointing sales, inadequate publicity, worse than inadequate royalties, idiotic or criminal reviews, others’ declining talent, and the unspeakable horror of the literary life”. Gorey’s odd early figures are somewhat reminiscent of the comic art of contemporary cartoonists James Thurber and William Steig of the New Yorker; and his extraordinary pen-and-ink work in the Victorian manner could be as dark and densely crosshatched as that of Edward Ardizzone, a British illustrator whom Gorey greatly admired. The influence of the celebrated etchings of George Cruikshank and Hablot Knight “Phiz” Browne for Dickens, too, is apparent. The book was issued in black and white to save the high cost of colour printing. As a result, Gorey explained: “I ended up thinking in black and white.”

It was a disturbing debut. British novelist Graham Greene called The Unstrung Harp “the best novel ever written about a novelist, and I should know!” But it baffled the public and did not sell. “For some reason,” Gorey told reporter Richard Dyer in the Boston Globe in 1984, “my mission in life is to make everyone as uneasy as possible. I think we should all be uneasy as possible, because that’s what the world is like.” He adhered to that “mission” throughout his prolific career. He immediately followed The Unstrung Harp (1953) with The Listing Attic, a minor masterpiece of the non sequitur. He had been writing and illustrating these droll but unconnected limericks for some time and finally put them together in 1954. Surely the most unnerving and amusing of the lot for the time was the androgynous couple in Herts who are “never without/Their mustaches and long, trailing skirts”. He infused these little verses with whimsical menace. He got in the habit of drawing to scale so his highly intricate drawings were often no more than four inches square. He made the mistake of turning in the dummy of The Listing Attic with the text all hand-lettered rather than set in type. It had been purely a practical decision, but the editor liked the effect so much that it was published exactly as he delivered it as if the penmanship were part of the design. Gorey regretted it afterwards for he then felt obligated to hand-letter his subsequent books. He wrote out even the copyright pages and the printing history on the versos of copyright pages as well as the flap copy on the dust jackets and colophons of limited editions of his books.

He produced more than 100 titles that he both wrote and illustrated. Some were no more than pamphlets, others wordless suites of pictures. Although he rarely reread his work, he told Theroux in 1974 that, of all his books, he preferred The Nursery Frieze (1964), a series of often obscure and difficult nouns printed on a streamer of parading beasts, and [The Untitled Book] (1971), another collection of nonsense phrases and creatures in imitation of an early 19th-century toy book. Gorey said these were harder to do than his others as they shunned traditional narrative or logic, but he was happy with the results. He also liked The Object-Lesson (1958), the incongruous and severely disjointed narrative that begins with a missing artificial limb and goes blithely on from there. Inspired by Samuel Foote’s nonsensical recitation The Great Panjandrum, from about 1755, one silly scene melts into the next like the stream of consciousness of a madman. It is pure absurdity.

No one knew exactly what to make of this comic Grand Guignol. Gorey failed to get any books published between 1954 and 1957. At first there were few reviews except at times in the provincial press. “Gorey is for sophisticates only,” Walter B Greenwood declared in the Buffalo News in 1963. “Most will call it ‘sick’ – mild case –and let it go.” Some thought he was morbid. They did not get it. They just did not get it. One had to have a sense of humour to be in on the joke. His little books did not sell and were soon remaindered for as little as 19 cents a copy. Nevertheless, Nobel Prize-winning author Hermann Hesse highly recommended to Swiss publisher Daniel Keel of Diogenes that he issue a German edition of “a fantastic picture book” he had just seen, Gorey’s The Doubtful Guest. Another early collector was Broadway composer Stephen Sondheim when he could pick them up for about a dollar apiece. No one took Gorey seriously until 1959 when his friend and great champion Edmund Wilson wrote an appreciation in the New Yorker. That year they both joined poets WH Auden and Phyllis McGinley to work on the short-lived Looking Glass Library, an eclectic selection of eccentric reprints as a “children’s counterpart to Anchor Books”. Not only was Gorey the series art director, he also provided wiry, spiky pictures for HG Wells’ The War of the Worlds (1960) and moody fine-etching-like drawings to The Haunted Looking Glass (1959), a collection of ghost stories Gorey himself selected. He found that sort of tale particularly challenging to illustrate because he did not want his pictures to give too much away. He later supplied the jacket design for Wilson’s The Duke of Palermo and Other Plays (1969); and the two later collaborated on the Christmas story The Rats of Rutland Grange (1973). Gorey, Wilson said, “has been working perversely to please himself, and has created a whole little personal world, equally amusing and sombre, nostalgic and claustrophobic, at the same time poetic and poisoned”.

Gorey’s cheeky satire made Wilson think of Aubrey Beardsley and Max Beerbohm as well as Max Ernst, especially in Ernst’s surrealist pictorial novels of visual paradox La femme 100 têtes (1929), Rêve d’une petite fille qui voulut entrer au Carmel (1930) and Une semaine de bonté (1934) in which he secured the most striking effects with collages of contrary details cut from cheap banal popular 19th-century wood engravings. Gorey mastered this art of incongruous pastiche through the discriminating juxtaposition of elements from various trite sources. Experimental novelist Donald Barthelme noticed Gorey’s affinities with Magritte, Hiroshige and Gertrude Stein, the High Priestess of Camp, and spoke highly of “Gorey’s grimly risible moral instruction”. He added in his 1983 New York Magazine appraisal: “Gorey’s texts are as startlingly original as his drawings. One of the properties of language is its ability to generate sentences that have never been heard before.” Gorey acknowledged among his other unexpected artistic influences Michelangelo, Giorgione, Piranesi, Rembrandt, Vermeer, Frans Hals, Winslow Homer, Picasso, Giorgio de Chirico and Francis Bacon.

Wilson dared question Gorey’s French just as he did Vladimir Nabokov’s English. “He was always castigating my prose,” Gorey complained. But Gorey got his sly revenge: he dedicated The West Wing (1963), a wordless picture book, to the eminent American critic. His French was better than the critic thought: Gorey successfully translated and illustrated Story for Sara (1971) by French humourist Alphonse Allais, a warning tale about a deceptively good little girl who gets her comeuppance for being cruel to the birds. “Bunny” Wilson was always thinking about sex and insisted that Gorey get hold of the notorious French erotic bestseller The Story of O (1954) by Pauline Réage, but the artist found it dull. Gorey’s answer to that infamous piece of curiosa was the hilarious satire, the ironic “pornographic illustrated story about furniture”, The Curious Sofa by the ubiquitous Ogdred Weary. Here, all sexual indiscretions were shrewdly implied but never described nor depicted, proving that sex is as much in the brain as in the genitals. “People are always trying to find things that simply are not there,” Gorey protested in Newsday in 1994; “when it comes to my own [work], I think, ‘what’s to understand?’” It was all so absurdly innocent (“Still later Gerald did a terrible thing with a saucepan”). Had he just dropped “pornographic” from the title there would have been no trouble. “I drew The Curious Sofa over one weekend,” he said in New York Magazine in 1977. “One printer actually refused to put it into type. Even today I hear that some gentlefolk are scandalized. But the details of Lady Celia’s house party happen in the reader’s mind.” The Austrian Ministry of the Interior banned the German translation for potentially corrupting the morals of youth. And there was not a dirty picture in it! Nevertheless, Gorey was proud of what he achieved in The Curious Sofa. Publishers then offered him pornography to illustrate. “I would blush crimson at the other end of the phone,” he recalled. “I couldn’t possibly draw anybody of either sex doing anything.” He was shocked to learn that some boys and girls enjoyed the book. He told Filstrup he threw in “gimmicks to flatten the prose, like the constant reiteration of the ‘well-endowed young man’. A kind of poetry may come through to the child even though the phrase was put in as a parody on pornography where everyone is faceless, undifferentiated.” Perhaps the closest he ever came to depicting anything even slightly erotic was the picture of two reclining prostitutes with black bands across the naughty bits in The Fraught Settee.

When The Looking Glass Library failed, Gorey went over to Bobbs-Merrill in 1963 where he designed jackets and covers for its editions of Shakespeare’s plays. He left the publishing house two years later and freelanced for the remainder of his life. He recalled that at one time he had as many as seven completed manuscripts that he submitted to editors for their juvenile lists. “But they would not risk it,” he recalled. “They would get all twittery. So, I gave up.” To supplement his income in 1965, he taught courses in advanced children’s book illustration at the School of Visual Arts in New York. That year, his first one-man show opened in the California College of Arts & Crafts in Oakland; and, on occasion, he exhibited his drawings at Graham Galleries and Gotham Book Mart.

Not everyone got him or his work. In 1965, Gorey released an enigmatic statement about himself to put off the curious: “As to biographical material, my life is so featureless that after saying I was born in Chicago in 1925, graduated from Harvard in 1950, and now divide my time between New York and Cape Cod, there is nothing else to mention. I have no thoughts whatever about my work, none.” He emerged as an artist at about the same time as camp was drawing attention to itself as a cultural phenomenon. Today, it is as much a putdown as a put-on, an instrument of contempt. The essence of this elusive often highly affected anti-art art, argued queer intellectual Susan Sontag in her famous 1964 Partisan Review essay, Notes on Camp, is “its love of the unnatural: of artifice and exaggeration”. It held up a cracked mirror to the real world to be laughed at. “The more we study Art,” Oscar Wilde the Godfather of camp, noted in his essay The Decay of Lying of 1891, “the less we care for Nature.” Gorey agreed. He found inspiration in much of what Sontag termed Camp, including classical ballet and opera and the movies. In ruminating over the indicators of the phenomenon, she could have had Gorey specifically in mind. She pointed to specific examples that inspired him: the novels of Firbank and Compton-Burnett, Beardsley’s drawings; “women’s clothes of the twenties (feather boas, fringed and beaded dresses, etc)”; and “decorative art, emphasizing texture, sensuous surface, and style at the expense of content”. Gorey is a master class in camp. This is not a criticism: it is an acknowledgement. “Part of me is genuinely eccentric, part of me is a bit of a put-on,” he admitted to reporter Lisa Solod in Boston Magazine in 1980. “But I know what I am doing.” He was clearly in on the joke.

Camp seemed rife with contradictions. One could revel in it while at the same time ridiculing it. As Sontag said: “The ultimate Camp statement: it’s good because it’s awful.” She described the nebulous nature of the sensibility at the time as “a mode of enjoyment, of appreciation – not judgement”. And Gorey was having a lot of fun. His work was indeed “the proper mixture of the exaggerated, the fantastic, the passionate, and the naive”. There was no real difference between the highbrow and the lowbrow. His shrewd sophistication is often highly subversive. It was all in how it was perceived. Camp for one is not necessarily camp for everyone. And Sontag was dead wrong about certain things (for her, the late Henry James of The Awkward Age, The Wings of the Dove and The Ambassadors is camp; she called Trouble in Paradise and The Maltese Falcon“among the greatest Camp movies ever made”). According to Wilde: “In matters of great importance, the vital element is not sincerity, but style.” Camp favoured surface over substance, manner over material. According to Sontag: “Camp introduces a new standard: artifice as an ideal, theatricality.” At times it was just a big goof. It defies definition. Camp is an attitude, a pose as much as a philosophy, the ultimate of cool for those in the know. It is an ironic sensibility that emerged from tightly closeted queer culture. It remains elusive: “It’s a gay thing you wouldn’t understand!” According to Sontag: “The whole point of Camp is to dethrone the serious.” And yet she vainly tried to make sense of what is fundamentally nonsense. She tried to define the undefinable. It is a volatile, floating sensibility that is so dependent on pop culture that what is considered camp today might not be tomorrow. Taking oneself so seriously without a drop of humour was futile. Therefore, Soviet social realism is the pinnacle of camp. There was absolutely no importance in being earnest. By taking the frivolity of camp far too gravely, Sontag (as she feared) made her essay in essence high camp. Most modern art criticism by its very nature is an unwitting form of camp. She insisted that those “who share the sensibility are not laughing at the thing they label as ‘camp’, they’re enjoying it.” Maybe Sontag was not laughing, but Gorey was. The unforgivable sin according to camp was to be bored or boring.

“One of the things you want to remember is what the 1950s were like,” warned Lurie. “All of a sudden everybody was sort of square and serious, and the whole idea was that America was this wonderful country and everybody was smiling and eating cornflakes and playing with puppies.” Gorey challenged the conventional, the truisms of modern life and mass culture. The warning of Gorey’s raven in The Epiplectic Bicycle (1969) when compared to the more exacting one of Edgar Allan Poe’s is pure camp: “Beware of this and that.” Camp had no patience with what Sontag termed the “the pantheon of high culture: truth, beauty, and seriousness”. It resembled Dada and futurism and even surrealism in overturning all preconceived standards of fine art. It was a hard slap in the face of public taste, as the Russian avant-garde might have termed it. Camp flipped conventional wisdom on its ever-loving ass. “It neutralizes moral indignation, sponsors playfulness,” or so said Sontag. The classic camp sentiment was Wilde’s observation: “One must have a heart of stone to read the death of Little Nell without laughing.” Camp provided a defence mechanism for those closeted individuals who struggled to survive in a world that criminalised their private behaviour. It was as a much a protest as a paradox or parody. These iconoclasts could not take anything that seriously. Not a single sacred cow was left unmilked. Perhaps the campiest of Gorey’s albums was The Loathsome Couple (1977), because it is so outrageous. This alarming satire of the Moors Murders, a real modern English murder case, concerns a pair of serial killers, a man and his girlfriend, who tortured and sexually violated children and buried their bodies on the Moors. While some people were shocked and offended that anyone would make light of so loathsome a killing spree, the Moors Murders had so affected him that it took him years to complete The Loathsome Couple. He was happy with the results. His editor, Robert Gottlieb, did not find it very funny. “Gee, what makes you think I think it’s funny?” Gorey wondered. That was such “a peculiar reaction”. It was as absurd as interpreting Gorey’s The Evil Garden (1966) with its delicate line drawings as a metaphor of the death camps in the second world war. Is there any sense in nonsense? Must there be?

One thing that Camp is remarkably good at is masking kitsch as high art. The tasteless had as much value as the tasteful. Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, Robert Rauschenberg, Claes Oldenburg and other pop artists understood that. Gorey did too. He produced a rich heady visual bouillabaisse drawing on everything and anything from penny dreadfuls to Japanese woodcuts. He readily threw into the seething pot whatever struck his fancy at the moment. No matter how ironic and violent his work might be, Gorey was never malicious, never cynical. He preferred to be playful. Arguably the campiest thing he ever did was dedicate The Abandoned Sock (1972) to a brand of soap. “Who could resist a name like Velveola Souveraine?” he defended himself.

Artists of the swinging sixties knew the Rumpelstiltskinesque trick of turning kitsch into gold. There was always something like The Emperor’s New Clothes about camp: it was art because it was sold as art. What once seemed revolutionary and dangerous has since become convention. The illegitimate has become legitimate. Bad taste is now fine art. The hollowest portraits of Marilyn or Elvis today hang in the hallowest halls of the world’s great art museums. But when Warhol said there was no there there, believe him. That is the point.

Camp was a gay sensibility long before “gay” or “queer” was a respectable critical term. Those who bore this sensibility were, said Sontag, “an improvised self-elected class, mainly homosexuals, who constitute themselves as aristocrats of tase”. In matters sexual, according to Sontag, Camp challenged conventional beauty, preferring either the androgyny of knights and ladies of the pre-Raphaelites or the hypersexuality of Jayne Mansfield and Victor Mature. It was passionate and naive at the same time. “When something is just bad (rather than Camp),” she argued, “it’s often because the artist hasn’t attempted to do anything really outlandish. ‘It’s too much’, ‘It’s fantastic’, ‘It’s not to be believed’ are standard phrases of Camp enthusiasm.” Gorey merely called it “fabulous”. He took the silly minutiae of pop culture and dressed it up in Victorian garb. He skilfully played with vulgarity without being vulgar himself. That baffled people who did not get the joke. They studied the surface and thought that was all there was.

No scandals, erotic or otherwise, marred his relatively quiet life. Gorey was always rather ambivalent about his own sexuality. “I ask myself why I never ended up with somebody for the rest of my life,” he told Richard Dyer in the Boston Globe Magazine in 1984, “and then I realize that obviously I didn’t want to, or I would have”. He was not asexual as some have assumed. He had his crushes on men, usually older, but he seems not to have enjoyed sex much. According to Alexander Theroux’s biography The Strange Case of Edward Gorey (2011), the artist confessed: “I tried it once and I was quite disappointed.” Among his “crushes”, according to curator Hischak’s E Is For Edward, was the younger Tom Fitzharris, with whom Gorey exchanged 50 letters in decorated envelopes that are the basis for From Ted to Tom. From 1974 to 1975, Gorey pictured the two of them as mutts in letter sweaters; and he paid homage to their friendship in the two-colour L’Heure Bleue (1975). They parted company during their Scottish sojourn.

Director Mike Nichols once said: “Homosexuality used to be the love that dare not speak its name; now it’s the love that won’t shut up.” Gorey belonged to that earlier era when it was not mentioned in polite conversation. Everyone who knew him knew he was gay: he never disguised it and did not feel it was necessary to discuss it publicly. Did it matter? The important thing was that he was comfortable with himself. Reporter Lisa Solod sucker-punched him when she bluntly asked in her September 1980 Boston Magazine interview if he was a homosexual. “Well, I’m neither one thing nor the other particularly,” he coyly replied. “I suppose I’m gay. But I don’t really identify with it much. I am fortunate in that I am apparently reasonably undersexed or something. I do not spend my life picking up people on the streets … A lot of people would say that I wasn’t [gay] because I never do anything about it.” He wisely added: “What I’m trying to say is that I am a person before I am anything else.” The children’s illustrator and author James Marshall, best known for George and Martha (1972) and The Stupids (1974), noted that though Gorey had a boyfriend at the time, he was no longer sexually active by the late 1970s. In the end he confessed that the love of his life was his cats.

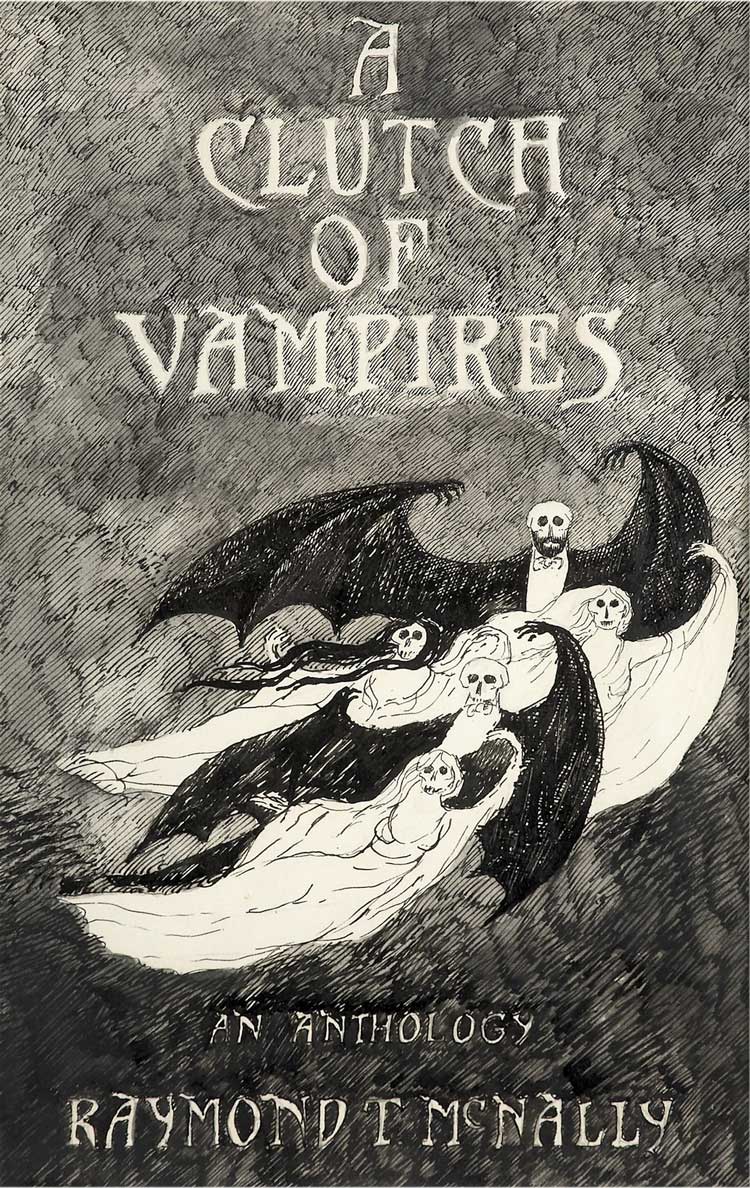

Cover art intended for A Clutch of Vampires, by Raymond T. McNally, 1974. Pen and ink on paper. From the collection of Russell Lehrer and David Rosen. Courtesy of The Edward Gorey Charitable Trust.

But why the fascination with violence and horror? He told Theroux in 1974, simply. “I write about everyday life.” While he may have at times played with the everyday, there is nothing mundane about his work. He was quoted in Newsweek in 1977 as insisting that the world is “dreadfully hazardous. I never could understand why people always feel they have to climb up Mount Everest when you know it’s quite dangerous getting out of bed.” Gorey has often been accused of drawing gratuitously gruesome subjects, but that is not true. All the horror lies in exactly what is not depicted. Suggestion is always more terrifying than graphic violence. “I don’t think my work is particularly gory, in the sense of bloody,” he told Mary Campbell of AP in 1994. “I think it’s weird. It is much more odd or bizarre than sinister. I don’t think of it as being nearly as sinister as other people sometimes do.” It was all about creating an appropriate mysterious atmosphere. Many adults confessed to him over the years that one or another of his books was a childhood favourite.

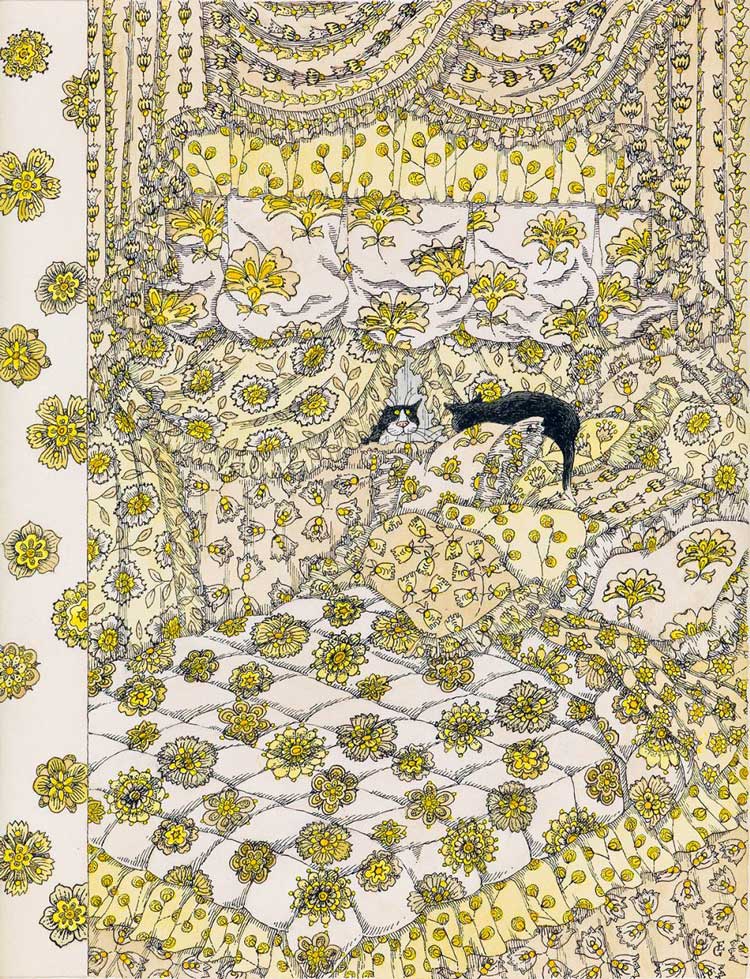

The Vinegar Works, an elegant slipcase of three startling individual picture books, The Gashlycrumb Tinies, The Insect God and The West Wing, appeared in 1963. It was even more subversive than his friend Maurice Sendak’s Nutshell Library that came out the year before. Perhaps Gorey’s was a gentle parody of the earlier boxed set. He wanted The Vinegar Works to be released to the juvenile market, but the publisher forbade it. Not surprisingly, Sendak disagreed with their decision: “Ted Gorey is perfect for children, and that’s the saddest thing of all, that [Gorey’s books] weren’t allowed to be published that way.” Gorey delighted in 19th-century lachrymose moral tracts in which good children were universally welcomed into heaven and bad ones went straight to hell. The fearsome lesson of The Insect God is obvious: “Don’t talk to strangers, children.” When little Millicent Frastley wanders off and makes the fatal mistake of getting into the wrong vehicle, she becomes a human sacrifice to a dreadful deity. It is as if Alfred Hitchcock’s birds were replaced by bugs. It was payback time for Mother Nature. The West Wing (originally titled The Book of What is in the Other World) is a deft tour de force of an ominous silent tour through empty rooms of unspeakable dread in an old mansion. Here, Gorey touched on all the cliches of haunted house literature as visualised in his ornate drawings. He explained in a 1963 interview that the West Wing “is where you go after you’re dead”. Terror and suspense arise from what is not shown rather than from what is. Gorey mastered the meticulous rendering in pen and ink of peeling wallpaper, intricate carpet, the grain of old wood panelling. He developed his distinctive style “somewhere between my 18th and 21st year and it was more or less full-blown”. The always self-effacing artist said in 1986: “Sometimes I think that my life would have been completely different if I had ever learned how to draw.” That was pure bosh: he drew beautifully with dizzying hair-fine precision. He never seemed to make a mistake. He never tidied up a drawing with Chinese White as did many other illustrators. There is always tension between his lines, the intense crosshatchings battling with rigid hachures in opposing directions, that he drew with the Goreyesquely named Gillott’s Tit Quills. His compositions often consist of undulating, pulsating, shimmering, agitated surfaces of discordant patterns.

No matter how seemingly distasteful the subject matter, the technique was always tasteful, almost precious. It was also labour intensive. It might take him two full days to complete a particularly complex illustration. He hated having to go back and redraw a picture. While working on The Hapless Child (1980), he had done five or six when he suddenly realised: “I am bored to death drawing wallpaper on the wall.” He put the book aside for five years before he could take it up again and finish it. Gorey’s startling masterpiece of infanticide is The Gashlycrumb Tinies, one of his Vinegar Works, the most remarkable of his “anti-alphabet books”, in which the name of an innocent child is attached to a different letter and a most particular horrific end. It concludes with a picture of a graveyard of all those unfortunate tots. Gorey’s personal favourite of the entire suite is the best of the ill-fated 26: “N is for Neville who died of ennui.” (“Gashlycrumb” was an afterthought: the working title was The Something Tinies.) Their sad demises were as terrible as any depicted in Heinrich Hoffmann’s alarming German classic Struwwelpeter (1845). (Gorey owned numerous copies of the book in German and English.) Some of the people in Lear’s Book of Nonsense, too, encounter violent ends. Yet those of the Gashlycrumb Tinies are rarely gratuitously gruesome. Atmosphere was everything. The unfortunate lads and lasses are shown being menaced rather than maimed. Even Rhoda consumed by flames is so exquisitely rendered that one does not at first realise exactly what is going on. The one false note is the brutally bloody “K is for Kate who was struck with an axe”. He was rather ambivalent toward his victims. He told Filstrup: “I aim to provoke a level of non-emotional response, as well as to keep myself distant.” The reader must keep telling oneself it is just a book … it is just a book.

The alphabet is the simplest of narrative structures with an infinite possibility of invention. Gorey gleefully filled his with infinite jests. He refashioned the ABC book for adults with sardonic quatrains of Victorian malaise in The Fatal Lozenge of 1960: for example, B is “The Baby, lying meek and quiet/Upon the customary rug,/Has dreams about rampage and riot,/And will grow up to be a thug.” Gorey’s fine ABC bestiary The Utter Zoo Alphabet (1967) was an obvious response to the imaginary menagerie of Dr Seuss’s alternative alphabet On Beyond Zebra! (1955): Gorey’s ridiculous creatures ran from A (“The Ampoo is intensely neat./Its head is small, likewise its feet”) all the way to Z (“What about the Zote can be said?/There was just one and now it’s dead”). Another alphabet gave him considerable trouble. He began The Chinese Obelisks in 1960 with unusually dense, complicated drawings, but he did not get past F. It took him 10 years to pick it up again; and he greatly simplified the illustrations. The Author who “went out for a walk” and gets fatally struck on the head by a falling urn is Gorey himself. The darkly malevolent The Glorious Nosebleed (1974), the Fifth Alphabet, amusingly explored adverbs from “Aimlessly” to “Zealously”. That last showed Gorey himself writing it all down … zealously. In 1983 came the miniature The Eccentric Abecedarium. In 1996, he produced the six quirky Thoughtful Alphabet broadsides (but numbered 2, 3, 4, 10, 14 and 15) for Gotham Book Mart. Another, numbered 8, was issued posthumously in 2001.

Booksellers did not know exactly what to make of all these odd little books. They usually shelved them under “Humour” beside anthologies of Peanuts and Li’l Abner comic strips or nestled with James Thurber’s collections, Tomi Ungerer’s The Underground Sketchbook (1964), or Shel Silversteein’s The Giving Tree (1964). Some clerks slipped them into the children’s section. Not that Gorey minded that. He was the master of moppet abuse. The parents of 11-year-old Ursula in The Remembered Visit (1965) take her on an excursion to Europe and then inexplicably abandon her. Then there was poor little Henry Crump in The Pious Infant (1966) by “Mrs Regera Dowdy”, a diverting sendup of James Janeway’s long-forgotten moral tract A Token for Children (1671); despite all his good works, the cursed three-year-old succumbs to incurable storybook disease after delivering bread pudding to a poor widow. It only goes to prove what Wilde observed: “No good deed goes unpunished.” Young readers went mad for these mad little books much to the horror of their elders. Gorey insisted that much of his work, like Struwwelpeter, was perfect pablum for the little ones. Many were intended for boys and girls. After all, Gorey was just a big kid from the middle west. (He confessed to Theroux: “Willa Cather can still make me weepy.”) The one shop that originally unconditionally embraced Gorey was the Gotham Book Mart in New York City. He first met the owner, Frances Steloff, in 1946, and forged an even closer bond with her successor Andreas Brown after she sold him the store for a dollar in 1967.

He proved to be Gorey’s greatest champion. Not only did he sell his books and exhibit his art, Brown became his publisher beginning with The Sopping Thursday (1970) when others summarily turned him away. He also served as Gorey’s archivist and stored the work at his place. Naturally, Brown was named an executor of the Gorey Estate. The quirky writer also developed a special rapport with Anne and David Bromer of Bromer Booksellers in Boston; they, too, eventually published several of Gorey’s books. Whenever Brown asked Gorey what a particular work meant, their creator invariably replied: “What you see is what you get.” He never explained, he never apologised. Some people saw Gorey as no more than a kiddie lit Charles Addams. Walter B. Greenwood argued in the Buffalo News in 1963 that Addams “achieves laughter through broad exaggeration. Gorey’s work is neat and precise. It will evoke a weak and sickly smile at most.” Any comparison only annoyed both artists. There was one major difference between these two masters of the macabre, as the critic Mel Gussow pointed out in the New York Times in 1994: “Gorey’s tales are cautionary, offering moral instruction and tearful laughter.” Gorey also warned: “To take my work seriously would be the height of folly.”

As he recalled to Paula Span in the Washington Post in 1991, Gorey tried to peddle his manuscripts to juvenile departments, but editors told him: “Oh no, that wouldn’t do at all.” Oh foof,” was how he replied to rejection. So, in 1962, the artist founded Fantod Press to publish his own books. (“Fantod” is a Victorian word for “heebie-jeebies,” or as Gorey explained, “the vapors, the nervous tizzies”.) In all, it published 28 titles that commercial publishers shunned. The pamphlets were often offered in trios in Fantod Press envelopes. Initially, Gorey thought of publishing all his works under pseudonyms. His own name sounded like a pen name and some people thought it was. This master of anagrams came up with such delicious ones as Roy Grewdead, Raddory Gewe, Dreary Wodge, Drew Dogyear and Wardore Edgy. He could get carried away with the conceit of pseudo-anonymity: for example, The Stupid Joke (1990), a cautionary tale with a melancholic end for a little boy who refuses to get out of bed, was written by Eduard Blutig, translated from the German by Mrs Regera Dowdy, and illustrated by O Müde. (“Blutig” is German for “gory,” “müde” for “weary”.) Gorey took his chunky oblong format from old English toy books and moral tracts. His pen work was as precise as copperplate etching and the texts hand-lettered in the same rigid manner as that of William Roscoe’s The Butterfly’s Ball (1802) and its many successors with a full-page illustration facing a few lines of text on the opposite page. At first, these John Harris toy books were all hand-etched. Beatrix Potter, an artist Gorey admired, adopted a similar format in her famous Peter Rabbit Books. He preferred to call them “albums” rather than “picture books”.

“I’m a great admirer of the 19th century,” he told the Los Angeles Times in 1986. “I think people then knew much more what was going on, were more in touch with what life is really like, than we are. I’d prefer to see a good rousing 19th-century melodrama than something by Robert Wilson any day.” This modern Miniver Cheevy always seemed out of touch and out of his own time, for ever lost in severe anemoia, longing for an era he never really knew, but always with his tongue firmly within his cheek. He was intrinsically ironic. His style could be at once cosy and creepy. He was consistently self-consciously archaic as he inserted details cleaved from Dover books on 19th- and early 20th-century design. He was but an anachronism within modern art, a sophisticated throwback winking at the vulgarity of the past while lamenting that of the present.

“I feel morally at home with the Victorians,” Gorey once told a reporter. “They are crazy in more interesting ways than we are.” Gorey inhabited his own atmosphere of sardonic doom and gloom. There is no nostalgia without a little pain. “I am greatly influenced by 19th-century illustrations,” he told New York Magazine in 1977. “They’re very sinister, but without decadence.” Frenchman Gustave Doré and Englishman John Tenniel immediately came to mind when he was pressed for influences. He also found delight in the anonymous cuts in early English toy books, broadsides, Banbury chapbooks and moral tracts. He thought “the only thinkable ones” for Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows were EH Shepard’s pen-and-ink pictures. He loved drawing period clothes and decor, and often borrowed form and substance from the Victorian period. A good example is The Iron Tonic (1969) that looks like a 19th-century advertising pamphlet with its ornate wintery black-and-white background landscapes and rondos of action. It was in part inspired by his maternal great-grandmother, an artist in her own right, to whom he dedicated the book. Things go horribly wrong and unresolved for the residents of a mysterious grey country hotel when unexpected objects tumble from the sky. They must remain and accept their fate much like the dinner guests in Luis Buñuel’s famous surrealist film The Exterminating Angel (1962).

Gorey did tend to get obsessed with certain archaic details: for example, the collection of pen-and-ink sketches Leaves from a Mislaid Album (1972) imitates a Victorian family photo album. Les Urnes Utiles (1980) is another wordless book and exactly what the title says – a collection of all sorts of decorative urns of various whimsical use. He was as obsessed as Beardsley was with horrible Victorian tassels: the phallic shape was likely what appealed most to both of them. Gorey based his wordless suite of unsettling pictures, Les Passementeries Horribles (1976), on his personal collection of these peculiar decorations. These giant monstrosities are pure menace as they lurk behind trees and pillars and outside windows and on the beach and hillside and elsewhere. The imagery is immediately uncomfortable and hilarious at the same time. “I get nervous if I have to do anything contemporary,” he said in the Globe in 1984. (A memorable exception is The Curious Sofa. He did a fine job with another tale of modern times, Florence Parry Heide’s The Shrinking of Treehorn of 1971. However, due to his predilection for the past, he suffered trepidations about illustrating the sequel.) As an admirer of Taoism, he was also fascinated with Japanese and Chinese art in which the essence of the subject was rendered in the fewest strokes of the pen or brush. He sometimes adopted the same manner of “leaving things out, being very oblique in what you’re saying, being very brief”. It was all his own peculiar brand of Zen.

Another profound influence on his sensibility was dance. He was a devotee of the Ballet Russes from the time he saw a performance in Chicago as a boy, and he adored George Balanchine (“the greatest genius in the arts today”) and New York City Ballet. His figures often strike ballet poses à la Balanchine. From 1953 until the famous choreographer’s death in 1983, Gorey tried to attend every performance when the troop was in town. (“Instead of deciding which nights to go,” he said, “it is easier to go every night.” He recalled it as “all one great glorious blur”.) He was quite a fixture at the theatre and members of the company were aware of this most devoted fan. “At first all you can see of [Gorey] is his beard and moustache,” choreographer Jerome Robbins wrote to a friend, “then you start to see his eyes and teeth and some of his expressions; then you notice all the rings he wears and finally the fact that although he wears a rather elegant fur-lined coat, his feet are shod in worn-out sneakers. As an added fillip you perceive that the skin between his socks and the cuffs of his pants is very white and crowded with black and blue marks.” But Gorey was picky and prickly: he was interested in Balanchine only and classical ballet left him cold. (He described Les Sylphides in the New York Times on 13 November 1973 as “where they’re all looking for their contact lenses”.) He eventually designed posters and other merchandise for the famous troop; and he paid loving tribute to Balanchine in The Lavender Leotard (1973). He hand-painted the ballerina’s skirt on the cover of each copy so it had the exact colour he wanted. His love for the ballet also permeates The Gilded Bat (1966), the saga of the unlikely named Maudie Splaytoe who rises to prima ballerina Mirella in La Chauve-Souris Dorée. He treated opera much the same in The Blue Aspic (1968). Gorey designed the Royal Ballet production of Robbins’ The Concert and Swan Lake for the Eglevsky Ballet. He later provided sets for Giselle performed by the drag dance troop Les Ballets Trockadero de Monte Carlo. In 1986, he designed the American Ballet Theatre ballet Murder, choreographed by avant-gardist David Gordon and featuring Mikhail Baryshnikov. Sadly, nothing came of a collaboration with choreographer Twyla Tharp, another artist he admired.

He deeply longed “to splash fresh paint on Gilbert and Sullivan”. He thought the Savoy Operas were the height of entertainment. “The musical theater has been downhill since then,” he concluded. He finally got the chance to design The Mikado at Carnegie Mellon in 1983. He loved old movies, too, particularly silent ones by the French film-maker Louis Feuillade, but thought the industry also had been going downhill after 1918, and even worse when they opened their big mouths and out came talk, talk, talk in the late 1920s. The Eleventh Episode (1971) packs all the excitement of an instalment from a silent “damsel in distress” serial like The Perils of Pauline (1914). The Secrets: The Other Statue (1968), Gorey’s homage to Jane Austen, is another story of children in trouble like the introductory segment of a movie mystery full of suspicious characters including Gorey lookalike Dr Belgravius. In the end, we are left with only secrets and no solutions like the incomplete The Mystery of Edwin Drood (1870) by Charles Dickens. DW Griffith’s silent classic Broken Blossoms (1919) starring a much-abused Lillian Gish in part inspired The Hapless Child. (He dedicated The Willowdale Handcar in 1962 to the silent film star in memory of the two-reelers she made with Griffith.) He also said the idea came from a long-forgotten picture of 1905, L’Enfant de Paris, that he saw at the Museum of Modern Art. This melodrama of tragic absurdity, unfolding like William Hogarth’s The Rake’s Progress (c1735), traces the rise and fall of orphan Charlotte Sophia who is bullied by classmates and abused by teachers, apprenticed to a drunken thug, goes blind by making paper flowers, and is run over by her father who does not recognise her. The text serves as title-cards. It was about the only disappointment for him in his long productive career. “It is so overdone,” he said in the Boston Globe Magazine in 1984, “it tips over into being sentimental in a reverse kind of way.” He tended to draw the cultural line at the Wall Street Crash of 1929. He had little interest in what happened after that. Oddly, on occasion, Gorey did review new movies for the Soho News. He did not care for most of them and went anyway. He estimated that at one time he saw about 1,000 films a year.

People Weekly once called him “Charles Schulz of the macabre”. He never cared for that word “macabre”: he preferred “mildly unsettled”. If he had to call his work something, it might be “surrealistic” or simply “nonsense”. The people who inhabit his country of empty hallways and vast eerie landscapes seem perpetually and obliviously cursed. He revealed dangers that lie hidden beneath genteel society. “To enter the world of Edward Gorey is to step into a kind of parallel gothic universe, full of haunted mansions, strange topiary, and equally haunted and strange human beings,” his old friend Lurie observed in the New York Review of Books on his death in 2000. “Though they are mainly well meaning and well dressed and live in surroundings of slightly decaying Victorian or Edwardian luxury, they tend to seem baffled or oppressed by life. They play croquet and go on picnics and have elaborate tea parties, but somehow something always goes wrong. There are sudden deaths and disappearances, and they are often haunted, not only by ghosts but by strange creatures of all sorts, some of which resemble giant bugs, while others suggest hairy wombats or small, winged lizards.”

He created a definite Gorey type: he distinguished one character from another through changes in their clothes or hairstyle. If his solemn ladies and stoic gentleman belonged anywhere it was to the decline and fall of British empire, all of them oblivious to whatever the heartless gods have in store for them. Something or someone is always falling from the sky or lurking in the corner to commit cold-blooded murder. (Is there any other kind?) Gorey once accurately described his books “as Victorian novels all scrunched up”, a triple-decker in merely 32 to 64 pages. Several, such as The Green Beads (1978) and The Retrieved Locket (1994), are ironic exercises in happenstance. Of course, Gorey was rather loose with that form and meaning: for example, he called the non sequiturs of The Grand Passion and The Doleful Domesticity (1992) “two novels”. One of the more whimsical and abstract of his early tales is The Inanimate Tragedy (1966) all about such common household items as a marble, a thumbtack, two buttons, some string and a pen point with a Greek chorus of pins and needles. It comes closer to the pathos of Hans Christian Andersen than anything else Gorey ever wrote. The inexplicable remains unexplained: bizarre creatures appear out of nowhere in The Sinking Spell (1968), The Osbick Bird (1970), The Tuning Fork (1990) and other works as if by some perverse divine intervention. Theroux summarised “Gorey’s entire canon” in 1974 as “a purgatory of muffled hysteria, danger, and attrition, where endings are invariably inconclusive but always abrupt. He provides no solutions. Matters are simply dropped.”

Gorey was as inventive with language as with images. He introduced such delectable nonsense words as ganosis, gryphoemia, idiotocon, ignavia imbat, impyroghea, ophymirage and opopanax. He created characters with Dickensian names such as Jasper Ankle, Titus Blotter, Dick Hammeclaw, Emblus Fingby, Miss Scrim-Pshaw, Miss Squill, Mrs Umlaut and Lord Wherewithal, the Earl of Thump and Lady Emily Lisping who inhabit unlikely places like Penetralia, Hiccupboro, West Elbow, Nether Postlude, Bogus Corners, Godly Wot, Sludgemouth, Great Trackless Swamp. They attend Mrs Underfoot’s Seminary and a baked-bean dinner at Halfbath Methodist Church, wash with Grudge’s Cucumber Soap and take Orphobismic Lozenges and the miraculous “QVR”, “The Universal Solvent”. Recurrent devices in his books include the indescribable Figbash and the ubiquitous Black Doll. He often consulted The Dictionary of Difficult Words for unexpected obscure vocabulary. He learned early on that he needed to complete the text before he could commence the pictures. “If I start doing the drawings before the text is finished,” he explained in the Globe in 1984, “something happens to the book and it disappears”. He always found writing much easier than illustrating. He might dash off a text in an afternoon; others took years to complete. “I think of myself as primarily a writer anyway,” he once admitted, “the writing is what’s holding the whole thing up.” Then there were the dazzling wordless books beginning with The West Wing, collections of intricate drawings somehow loosely thematically linked but with no texts whatever.

There were quite a few manuscripts he never got around to embellishing; and he rewrote the two Fletcher and Zenobia stories by Victoria Chess who also supplied the pictures. “When I’m writing,” he explained to Campbell in 1994, “I allow for illustrations, so to speak. I try not to see things too clearly before I draw them, because only disappointment ensues.” Some projects were left undone, such as the intriguing The Interesting List that he never turned in to the legendary children’s book editor Ursula Nordstrom of Harper & Row. Instead, he designed the jackets for Mary Rodgers’ Freaky Friday (1972), A Billion for Boris (1974) and Summer Switch (1982). He did not always see things as others did. When Lodge (inaccurately) asked why there was no Gorey book with a happy ending, Gorey replied: “I don’t think it’s particularly relevant. Some of my endings I would consider happy, but nobody else would.” He was remarkably generous with his work. In 1993, Gretchen Adkins, a great collector of alphabet books, fervently admired his work and called him up in Barnstable to ask if she might interview him for her N is for Newsletter. He not only graciously agreed but allowed her to print three previously unpublished alphabets from his files in her journal.

For years he divided his time between his one-room apartment in the Murray Hill section of Manhattan and the large house on Cape Cod surrounded by relatives in the summer. He swore The Deranged Cousins (1971), the tragic tale of three bickering relatives, was based on them. Marshall visited Gorey in Barnstable in 1975. He noted in his diary how Gorey, “his big rings clacking on the steering wheel, picked us up in his yellow bug, fast for me and tends to tailgate”. The typical 18th-century Cape Cod house was filled with aunts and cousins (“he’s like sole eunuch in a gynaeceum”). His doubtful guest anticipated “all of Ted’s relatives to be sitting around in beards, wearing raccoon coats with lots of jewelry”, but they proved to be “perfectly normal”.

He had to see where Gorey did his work. “Ted’s own little hideaway is up in the attic,” Marshall went on, “and it’s just as I would expect: books collected through the years lined all the walls and are crammed into cranberry crates in the center. The five cats live up there with him and have a field day climbing on all the rafters, which are hung with a collection, also going back many years, of Mexican dragon figures and skulls, stalks of reeds, this and that. Three large windows with two comfortable old chairs look out on the harbor. It’s a large, cluttered room with an equally cluttered little cubbyhole in back which is his bedroom and studio … It’s dark and dusty and very makeshift, unfancy up there, a Cape Cod translation of his New York apartment, and I couldn’t imagine it any other way.” He did all his drawing there at a table. Since he drew generally to scale, he did not need much room. Theroux was also startled by Gorey’s quarters: “Your legendary Goreyesque room: a jumble of antiques; humped chests; sea stones; hempen figures; candlesticks; pots and potsticks; books; glass eggs; skulls and skeletons of all shapes (sent to him by admirers? alchemized? snatched out of crypts?); and, of course, row upon row of frogs: wooden, ceramic and beanbag. It is a gorgeous clutter, and one can almost feel within the place the ghostly presence of some of Gorey’s creatures, the Throbblefoot Spectre, the Wuggly Ump, Beëlphazoar, or the Raitch.” Gorey was in charge of the cooking. At dinner someone mentioned that one of their ancestors was buried with her bicycle. “Walking around with Ted and talking about all sorts of silly things,” Marshall recorded, “I forget that this is the man I’ve known and thought about for years through those drawings, some of the most unique work I’ve ever run across.”

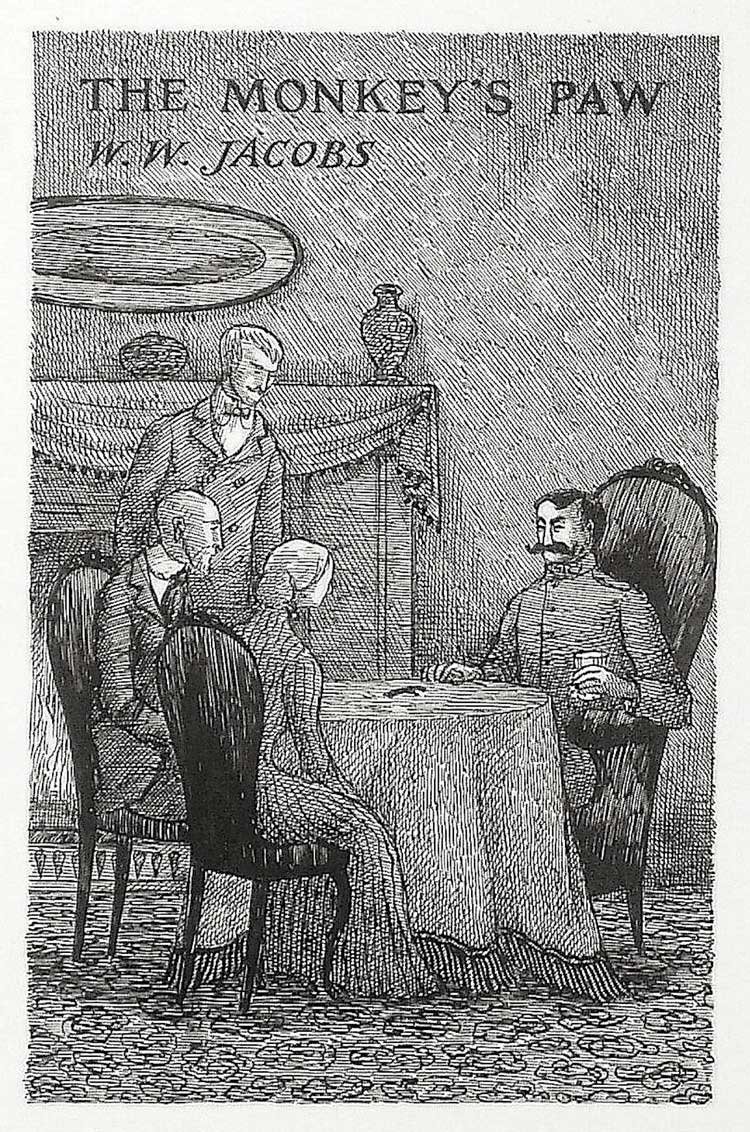

The Monkey's Paw from The Haunted Looking Glass, published by Looking Glass Library 1959. Courtesy of The Edward Gorey Charitable Trust.

Another harmless obsession was collecting stuffed animals of all sorts. Not only did Gorey readily accumulate them, but he gave to lucky friends and collectors the strangest soft toys – cats, bats, dogs, frogs, salamanders, rabbits, penguins, elephants, an occasional alligator or dragon – that he himself cut out, sewed together and stuffed, usually while watching soap operas and sitcoms. The most desirable and common of these curious beanbags was Figbash, the versatile recurring character of undetermined species introduced in the nonsensical The Raging Tide (1987). This is one of the most bizarre of Gorey’s books: a delightful, challenging make-your-own story in which the reader must answer a multiple-choice question; and depending on what has been chosen, one is directed to another page to continue the adventure. The characters all look like toys, once much beloved, who inhabit a surrealist country full of giant thumbs jutting up everywhere. Figbash proved to be one of the most flexible of Gorey’s inventions; and he twisted it into all the letters of the alphabet in Figbash Acrobate (1994). Gorey initially stuffed his home-made playthings with rice: that had a tendency to attract bugs and mice. Less tempting fillings were eventually used. Later he licensed some of them to toy companies so they could be commercially manufactured and distributed.

I used to run into him around New York usually at Lincoln Center or Gotham Book Mart. I did not know him well. We briefly corresponded. All I needed to do was address a letter to “Edward Gorey, Barnstable, Mass” and he got it. I watched him saunter about the New York Antiquarian Book Fair in full fur, browsing through the booths and picking out an occasional obscure volume or two that caught his eye. Fur was his all-weather gear. He was now playing a character called Edward Gorey. He embodied Oscar Wilde’s declaration: “One should either be a work of art, or wear a work of art.” Village Voice columnist John Wilcock described him in 1962 as “something of a cross between DH Lawrence and a medieval saint”. He was mistaken for a sort of gay goth beatnik. While immediately recognisable, Gorey was not famous then. When it became fashionable for men to wear a single earring in the 70s, Gorey was the first I knew who bore a pair of them. He moved freely about the city and once stopped by my apartment with a mutual acquaintance on his way to the ballet. His friends all had stories about him. He rarely said a word. Topics were usually limited to the movies or television shows he had seen or what he was reading. “One would automatically assume that Ted, having particular, limited interests in his work, would read only those books that followed those interests,” Marshall observed. “But that isn’t the case. He reads things I would never expect, and his interests could be described as very broad.” And: “He’s capable of reading several books at the same time: his bathroom book, bedroom book, upstairs and downstairs book, his sad deep book and his happy days book.”